In this tale of three urban wetlands across three continents, I’m struck by the importance of balancing access and ecological integrity. Surely the promise of these reserves can only be maximized by providing the public the opportunity to experience the riches they hold, while maintaining their integrity.

Madagascar is well known for its incredible biodiversity; the lemurs, chameleons, and the baobabs are, for good reason, recognized as the environmental rock stars of the island. In July 2019 I landed in the capital of Antananarivo to participate in the 56th meeting of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation. I arrived a couple of days early but didn’t have time to truly explore the country. Instead, when I got to the hotel I looked at Google Maps and searched for green spaces nearby to explore. A 20 minute walk would take me to a green spot called Parc de Tsarasaotra.

Parc de Tsarasaotra

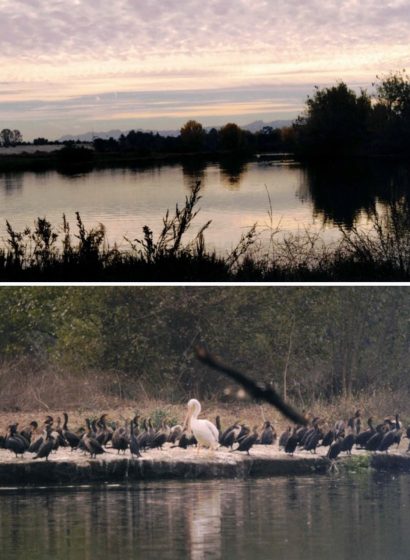

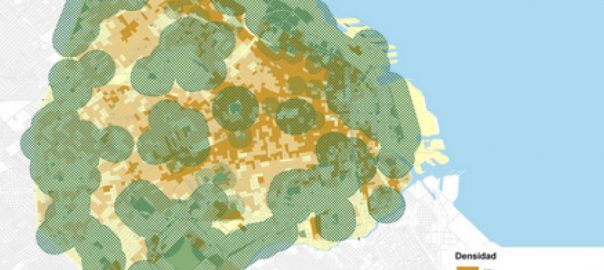

I searched on Google for details of Tsarasaotra and didn’t find a whole lot. It was clear to me that it was a restricted access site and had open hours. Wasn’t sure where to buy a ticket though. I discovered it was a Ramsar Convention site and thus of international importance. Surprising given its small size and location right in the middle of the city! In fact it is one of the smallest Ramsar sites in the world. The wetland is home to endangered and endemic waterfowl that make use of the habitat for roosting and feeding.

The next morning I got up at a reasonable hour and walked to the park following the map on my phone. When I arrived to the point where Google Maps pointed me to I came to a large wall. Dozens of ducks and herons were flying overhead into and out of the park. But without wings I would need to find an entrance. I darted in and out of the crowds as I followed the wall around the park.

Finally, having circled nearly the entire park (actually, it only took about 10 minutes) I found a gate with a clear view of the wetland. I walked up and was met by a low-key guard who said “20000 Ariary” (about $US5). I gave him the cash and walked in. The small wetland was empty but for myself and thousands of ducks and herons. As I walked around the quiet park I found a Malagasy Kingfisher and some cool orbweaver spiders.

After about half an hour I left the park and was struck by how loud the city was as I exited the gate back into the city. With the tall walls it was easy to forget the dense city outside. And once back into the city, the presence of the wetland was not apparent other than the ducks flying overhead.

Mai Po

The experience reminded me of the Ramsar wetland located only an hour drive away from where I work in central Hong Kong: Mai Po Nature Reserve. (Disclaimer of sorts, I’m currently a member of the management committee of Mai Po.) Mai Po is considerably larger than Tsarasaotra and is surrounded by a relatively rural landscape. But urban encroachment in the landscape is rapidly advancing in both Hong Kong and in Shenzhen just across the bay (Deep Bay).

Mai Po is well known regionally and internationally as a birding hot spot. Rare and endangered shorebirds and, of course, the black-faced spoonbill make their homes in Mai Po. Visiting Mai Po requires more than walking up and paying someone as I did at Tsarasaotra. But with a little forethought and planning you can indeed arrange (and pay a small fee) to book a visit. World Wildlife Fund Hong Kong manages the reserve and is at present enhancing visitor facilities to improve access and visitor experience as well.

One of the more elusive creatures living in Mai Po is the Eurasian otter. Sharne McMillan, a PhD student at the University of Hong Kong, has been tracking and studying otter in Mai Po for a few years now. And though she’s personally never seen one, she’s found a lot of evidence of the species in the reserve in the form of camera traps and spraints (otter poop). She’s also spent considerable time interviewing fish farmers that live in the areas surrounding Mai Po. Interestingly, based on these interviews, it appears that otter are more widespread than previously appreciated… but still the species seems to be in decline and rare in Hong Kong.

Displaying and protecting urban wetland wildlife

Most urban greenspaces, as conventionally conceptualized, have open access (or something close to it). The idea is that the public can use these spaces, interact with biodiversity, get exercise, or otherwise make use of open space near where they live. Urban wetlands seem to be a bit different. Even if there were open public access there are few people interested in diving into a wetland or tromping through thick mud to get a close look at some ducks (who would fly away in such cases anyway). And if there were such people the damage to the wetland would be severe.

There’s a balance then in urban wetland management that seems especially delicate. Access tends to be restricted to protect the habitat and the species that live there. But in such cases, the case for conservation is made more difficult, or at least the direct benefit to people living closest to urban wetlands may not be so obvious.

Mai Po and Tsarasaotra are both spectacular sights, full of colorful birds and contrasting horizons of water and reeds plus skyscrapers in the distance (in Mai Po) or short two story buildings just outside the walls covered in drying laundry (in Tsarasaotra). These urban Ramsar wetlands hold important pockets of biodiversity and high-value conservation habitats. But the access is also valuable and visits to the sites could likely have considerable indirect benefits as well. So maybe these urban wetlands should be more open to the public?

Sepulveda Basin

As a kid growing up in the San Fernando Valley in Southern California, the Sepulveda Basin Wildlife Reserve was a special place for me. My dad and I would drive there early on Saturday mornings and count geese, look for loggerhead shrikes (wonderful little vicious bird predators), and watch raptors above. The reserve was key for my development into the environmentally minded person I am today. I honed my skills and grew a sense of awareness for ecological interactions.

It’s very easy to get to the Sepulveda Basin and access is basically free. You can go whenever you want and there’s no quota or visitor restrictions. As a consequence the Sepulveda Basin is very popular for birders in the San Fernando Valley and a lot of people visit the site daily.

This has not come without problems of its own, however. There are considerable public safety concerns at Sepulveda Basin and at times key wildlife habitat has been removed—for example a large vegetation clearing occurred in 2012 to manage the problem of “sex-for-drugs encampments” and other criminal concerns. In the Los Angeles area the homeless population has surged in recent years (~60,000 in LA County in 2019) and this has caused problems for Sepulveda Basin. Homeless encampments have taken over parts of the reserve. In addition to habitat loss, such pressure also leads to considerable pollution problems and other disturbance impacts. So maybe this urban wetland should have a large wall or restricted access to it?

Pitfalls and promise

In this tale of three urban wetlands across three continents, I’m struck by the importance of balancing access and reserve integrity. I don’t have specific recommendations on this issue for any of the urban wetlands. But surely the promise of these reserves can only be maximized by providing the public the opportunity to seethe riches they hold while not causing any deterioration of the habitat as a consequence of such access. Perhaps more so than other more purely terrestrial, or even marine urban green/blue spaces, urban wetlands have considerable challenges in meeting both goals of space for biodiversity per se and space for people (e.g. for recreation or environmental education). How to balance habitat and open space needs properly will depend on the context (the city, environment and population) surrounding the wetland of interest. On the other hand, when these challenges are met then the value of urban wetlands is exceptional, for biodiversity and humanity alike.

Timothy Bonebrake

Hong Kong

Leave a Reply