Truly addressing the climate crisis in cities may require embracing the mindset of a 16-year old climate activist who is not afraid to challenge every one of our assumptions about life as we know it.

For the most part the millions joining the climate strike marches in September did so in cities, filling the streets of 1,000 cities in 185 countries. While the urban landscape of cities around the world became an inseparable part of the climate protests, it also brought up questions about the role of cities in changing the course of action on climate change. If we accept Greta Thunberg’s narrative that “our house is on fire”, then a key question is what role cities take on themselves?

For cities, this is a burning question. Cities are at the forefront of dealing with the impacts of climate change, including extreme weather events, sea level rise, food and water shortages, arrival of climate refugees and health issues.

While some cities have been at the forefront of climate action (see many examples at C40 and ICLEI), recent studies suggest that most cities respond poorly to the challenge, in terms of both mitigation and adaptation. Moreover, cities with higher poverty rates seem less prepared to address climate impacts. This is not good news given that climate change operates as a threat multiplier exacerbating existing food security, health and other social problems. The stark reality is that nothing we have done so far has managed to move the needle in the right direction on climate action.

The current state of affairs, where cities worldwide (with some cities doing more than others) respond inadequately to the climate crisis, makes it clear that cities, similar to countries, address climate change incrementally and within the confines of the current system. Unlike climate activists, cities, in general, are not interested to “blow up the system”, at least not when it comes to climate change. This inability an/or unwillingness to challenge the status quo is a losing proposition for cities and the majority of the world population living in them.

To change this trajectory cities will need to pursue a different model of action, stepping away from incremental changes in favor of societal-level systemic change. Cities, which have been the driver of technological, cultural and political change for centuries need to figure out quickly how to step up to the challenge. For this, cities need to activate their inner rebel. But, what is the mindset of a rebel activist city? We think it may start with a few critical conceptual and perceptual shifts:

Overcome the red zone/green zone gap.First and foremost what climate activists all over the world are pressing for today is urgency. We have been sleepwalking the climate debate for decades and time is up. Cities can play a critical role in closing the perception gap. On the one hand we have the IPCC reports and overwhelming scientific evidence that suggest climate change is a threat requiring immediate and bold response. On the other hand, most people living in cities still live in a non-emergency state, where the day-to-day is not affected by climate change. If we think of it in terms of color coding scale, scientists suggest we are in the red zone (i.e. severe risk), while most people feel as if they are in the green zone (i.e. low risk). This gap is critical because it means that for the most part, even with growing climate impacts, many people still consider climate change as a distant threat, or what Michael Lewis calls a ‘fifth risk’: “The existential threat that you never really even imagine as a risk”.

Cities can change this. Out of all levels of governments, city governments have the most direct relationship with their population. Local elected officials are steeped in their communities. They should use this power to make climate change more prominent on everyone’s agenda. This is true both in terms of the challenges and the opportunities around climate change. Cities can help redesign their communications to convey a sense of urgency. Some important actions include declaring climate emergency, and continuously informing residents on current and future climate change impacts, using all communication channels available. At the same time, through planning and action, and by placing climate change at the center of every discussion, cities can help their residents imagine what a zero-carbon life would look like. Sam Knights of Extinction Rebellion writes in the book “This Is Not A Drill”: “We need to rewild the world. That much is obvious. But first we need to rewild the imagination. We must all learn how to dream again, and we have to learn that together. To break down the old ways of thinking and to move beyond our current conception of what is and what is not possible.” Cities are best positioned to be the places where we rewild our imagination, experimenting and demonstrating what the relationships with technology, nature and one another may look like in a post-fossil fuel reality that prioritizes values above value creation.

Focus on equity and wellbeing. Income inequality is bad for happiness and “trickle down economics” doesn’t work. Cities can and are getting richer without, for the most part, having these riches spread out across the city’s population. Cities with the highest income levels in the world can and have deep poverty, homelessness and health issues. Cities with the most advanced technological industries do not automatically reap the benefits for their citizens. Put simply, if the purpose of city government is to provide services that allow well being for all its population, then equity has to be the central pillar of any city policy. Equity will not just happen along the way and is difficult to be addressed after the fact. City governments should place equity at the center of their strategies with regards to all aspects of their operations.

When using precious urban land for new development, city government should consider who stands to benefit, who is sitting at the discussion table, how the new development might impact current residents, and whether that development is in line with the social, economic and environmental goals of the city. It is absolutely okay (and necessary) for cities to reject Amazon, Walmart, or any other company pursuing development if those companies are not committed to contributing their fair share towards the social, economic and environmental goals of the city. Similarly, when developing new sustainability and resilience plans, cities should consider the equitable distribution of resources, the spatial distribution of hazards and amenities and the spillover, downstream and teleconnection impacts of their plans.

New technologies for the common good. New developments in smart city technologies, Internet of Things (IoT) and social media are happening at a dizzying rate. Cities have a responsibility to ensure that these technological developments first and foremost help us understand, control and manage the transportation systems, materials and energy flows more efficiently, thus help support our core values and goals while protecting our safety and personal information. Allowing technology companies and corporations to introduce technologies that are not oriented towards these goals can be discouraged. Companies that produce disservices to our communities such as Amazon, Airbnb, and Uber, should be intensely regulated, taxed, or banned.

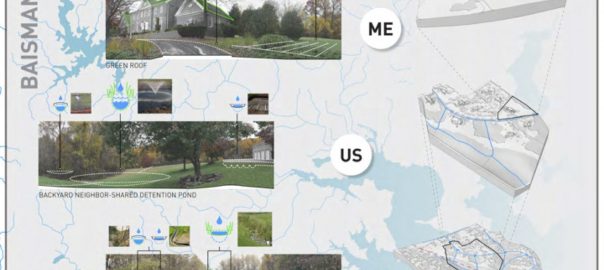

Many useful solutions are here and some cities already use smart technology and IoT for public transportation and traffic management, waste collection, street lighting, and energy efficiency. Cities have an important role in incentivizing these and other technologies that produce social-ecological benefits. Large scale implementation of green stormwater management, water and air quality, all have meaningful implications for urban sustainability and resilience that are not yet realized. Finally, cities should embrace initiatives and ideas utilizing technology to offer new visions for the production-consumption system that are based on decentralization, localization, open source and circularity, such as Fab City, platform coops, and local time banks.

Build humble infrastructure. As we toil in repairing highways and bridges (or tear them down), or play catch up with the implications of wastewater systems that are designed to send our waste down stream and into bottlenecks that are bound to overflow and pollute, coupled with growing stormwater flows over ever increasing paved surfaces, cities need to quickly learn to build humble infrastructure. We cannot afford another round of infrastructure that will lock us into one path of development for 300+ years. Cities must accept that we cannot know the totality of future consequences of what we build today. New infrastructure projects should take that into account, by investing in infrastructure with the least harmful environmental/sustainability/resilience effects (think trains and bike lanes vs. highways roads; solar panels vs. coal and nuclear power). Infrastructure design and engineering are some of the most rigid disciplines we have. Expanding the capacity to incorporate flexibility and build processes that take into account and leave space for change is their “be a Greta” task for the 21stcentury.

The climate emergency is a threat to almost every city on earth. To address this crisis effectively cities need to start thinking differently, and that may require embracing a mindset of a 16-year old climate activist that is not afraid to challenge every one of our assumptions about life as we know it. While it may feel uncomfortable doing so, dealing with the consequences of inaction will be much more uncomfortable. It’s time for cities’ leadership to decide if they are ready to step up their game and embrace an activist mindset, or they are afraid to do what it takes and prefer to remain a landscape in the protests of young people demanding change.

Peleg Kremer and Raz Godelnik

Princeton

about the writer

Raz Godelnik

Raz Godelnik is an Associate Professor of Strategic Design and Management at Parsons School of Design – The New School in New York, where he served for the past 3 years as the Co-Director of the graduate program in Strategic Design and Management.

Leave a Reply