As long as public transport and high-rise living is seen to be a “budget option”, the middle class is bound to aspire to vehicle ownership and detached homes as an upgrade. The solution could be counter-intuitive, but might lie in making these lifestyle choices more expensive, at least for some people.

The solution, some suggest, is to build affordable housing back in the city to reduce commute times and enhance livability for the growing middle class. But in a land-sparse city like Kuala Lumpur, this line of logic has led to defenseless green spaces being targeted for redevelopment, justified by the need for affordable housing. Several prominent green spaces in Kuala Lumpur have already been sacrificed, including football fields, parks, and even areas adjacent to forest reserves. How then can we ensure adequate provision of affordable housing while preserving nature in cities? Are both these aspirations a dichotomy?

Not necessarily.

The premise for divergence rests on the lack of land in the city. Land scarcity is in turn a function of city living preferences such as landed detached homes and car commute as the desired option. Cities can well afford more space for nature if preferences swing towards high-rise living and public transport-based commuting. Therefore, the true challenge is to convince the person on the street that nature in cities is of greater value than his or her middle-class lifestyle aspirations.

But how?

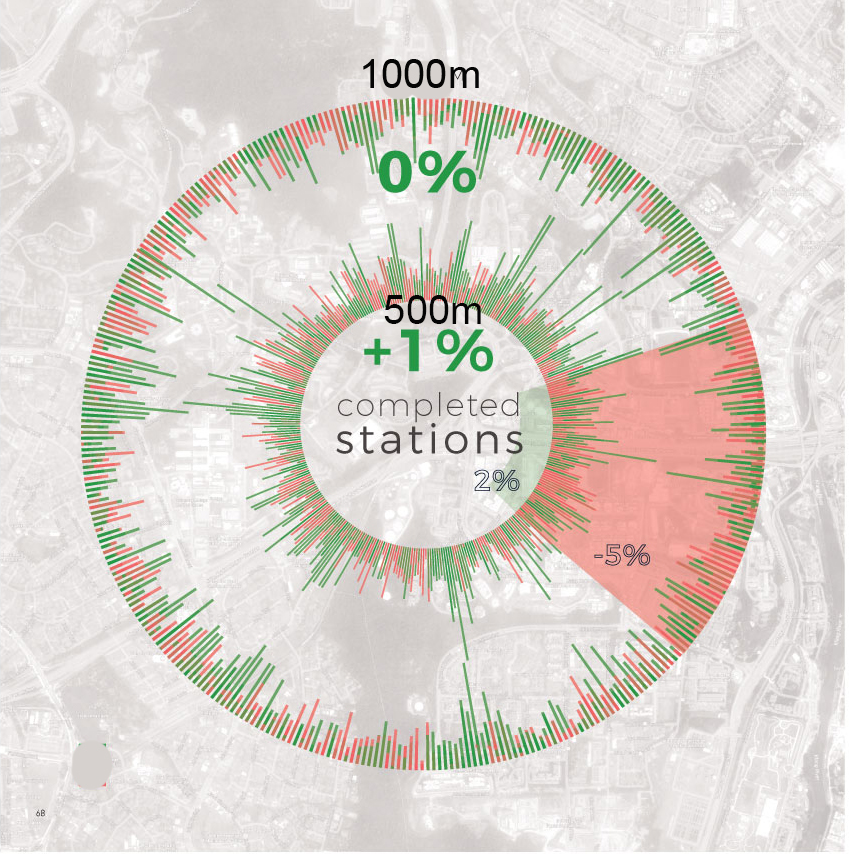

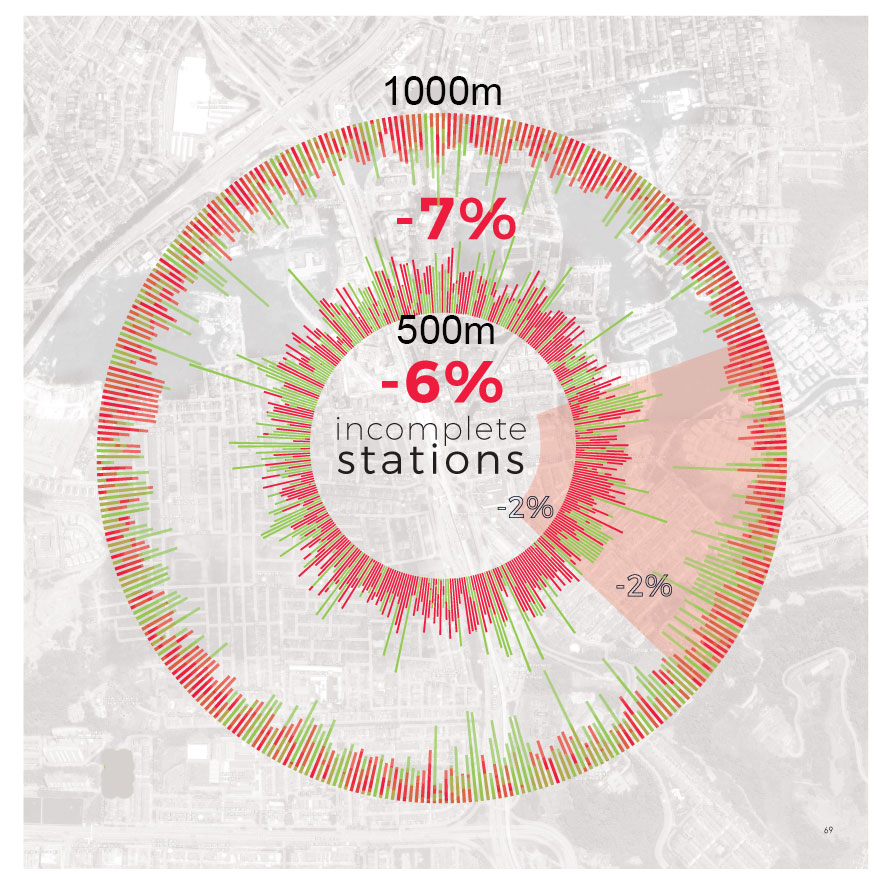

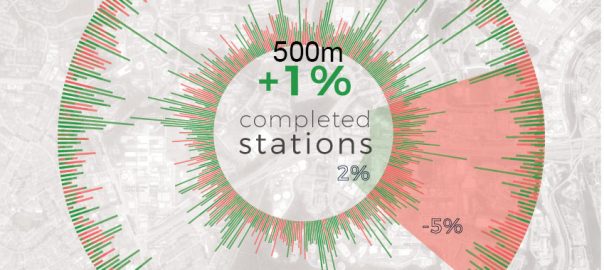

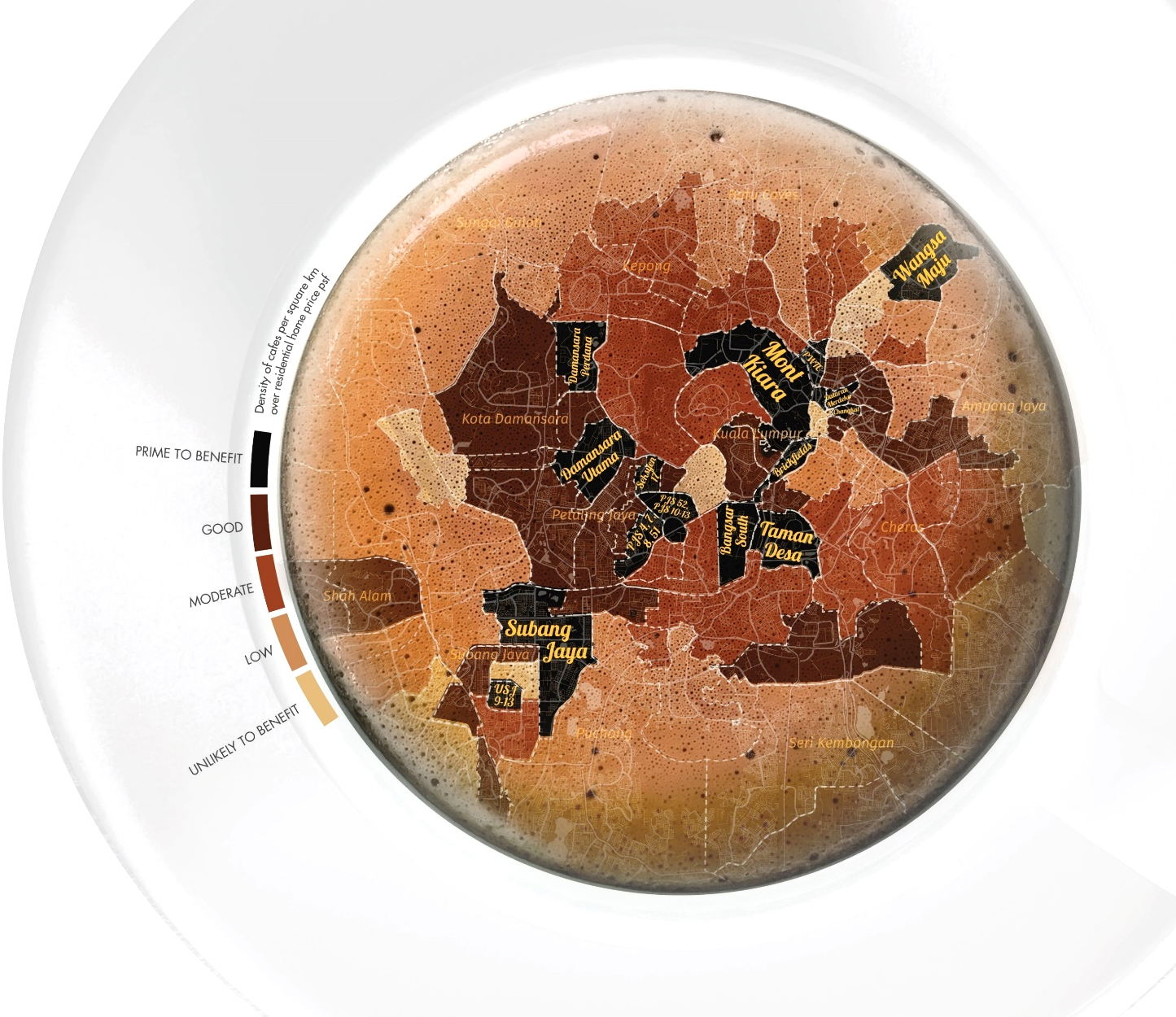

Like all sales tasks, the first step is to gather intelligence about our citizens and their current behaviors. Do they value living in high-rises or public transportation? Why not? In Kuala Lumpur, we attempted to understand this with data of home prices within walking distance of urban rail systems. Turns out, citizens are frustrated with station construction and prices of homes is practically flat on completion, indicating that residents don’t value public transport much currently.

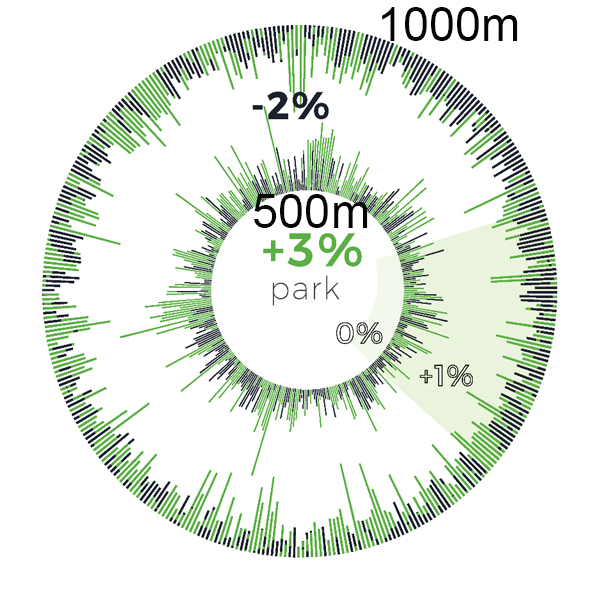

The second step to convert our middle-class neighbors into people who value green is to build rapport that resonates with their values and priorities. One way is to convert the value of “nature in cities” to a monetary value that they can directly compare to their immediate concerns of mortgages and housing value. In Kuala Lumpur, we achieved this by showing that homes within walking distance of green spaces were valued 3% higher than those without. In other words, the removal of parks and forest reserve translates to a $3,000 depreciation on a $100,000 home. Most middle-class folks would think twice before letting $3,000 wrung out of their wallets!

Perhaps the most complicated step would be step three, when we attempt to place our middle class to a desired future, where his or her change of behavior would bring a positive impact to their individual lives (not the greater good). A practical approach to this would be to highlight the individual wealth creation of public transport commuting and highrise living in a nature-rich city. In Kuala Lumpur today, 12.7% of household disposal income is spent on transport, which translates to $US3,338 annually, based on median income.

Perhaps the most complicated step would be step three, when we attempt to place our middle class to a desired future, where his or her change of behavior would bring a positive impact to their individual lives (not the greater good). A practical approach to this would be to highlight the individual wealth creation of public transport commuting and highrise living in a nature-rich city. In Kuala Lumpur today, 12.7% of household disposal income is spent on transport, which translates to $US3,338 annually, based on median income.

The monetary value would help with the rational hemisphere of the brain, but it boils down to the emotive aspiration that would turn the tables. This is because as long as public transport and high-rise living is seen to be a “budget option”, the middle class is bound to aspire to vehicle ownership and detached homes as an upgrade.

How then can we reframe this world view?

The answer could be counter-intuitive, but might lie in making these lifestyle choices significantly more expensive, at least for some people. Consider the Starbucks effect, which has benefitted coffee distributors all over the United States at the turn of the century. Starbucks gave all coffee and not just Starbucks coffee a new cachet, increasing the desirability of all coffees. In other words, the offering of a luxury version of a product could elevate the overall desirability of the product class of coffee without pricing people out, because not everyone needs to have Starbucks. In Kuala Lumpur, we see the rise of the cafes had such a strong impact that its presence impacted home prices.

Can this convert the middle class to nature-friendly city lifestyles?

The idea, like Starbucks effect, is to create a luxury brand could elevate the status of ALL types of coffee, while still maintaining the price range and options. Not everyone has to have a Starbucks but now there is more demand for coffee.

Similarly, not everyone needs a $50,000 bicycle but it might get more people to buy other bikes and use them instead of cars. We are beginning to see this change with the rise of ultra-luxury bicycles and the status that comes with penthouse living. Maybe, if all the marketing and advertising agencies harness their superpowers for nature in cities, public transport can be as sexy as the next BMW release.

Cha-ly Koh

Kuala Lumpur

Leave a Reply