Этот текст также можно прочитать на русском языке.

We asked local people what they wanted. And we tried to think about everyone who lives in this area or in the vicinity—people, birds, other animals, and plants—to strike a balance between urbanism and nature’s interests.

Background

For the last seven years, the development strategy of Moscow’s park grounds has undergone many changes. Large-scale landscaping efforts have been underway in city parks: over 500 natural areas in the city have been fully or partially redeveloped and turned into more “urbanized” areas, featuring more space in manicured settings for entertainment and sports. Wild grasses are replaced with artificial turf grass and mowed lawns, fallen leaves are removed, gravel paths cede place to paving tiles, and the greenery mostly includes aggressive invasive species, albeit with beautiful blooms. The selection of plant varieties does not in any way take into account their impact, including the negative ones, on local ecosystems. More than 50 billion rubles (around $US780 million) have been allocated so far from the Moscow city budget for these purposes.

The aim of the public program is to make natural areas look more manicured, thus ensuring, according to the authorities, a more comfortable pastime for Moscow residents. At the same time, according to the Birds of Moscow City and the Moscow Region program, the Zoological Museum, and the Biology Department of Moscow State University (MSU), the landscaping of citie’s parks brought about a drastic drop in nightingale, citrine wagtail, western yellow wagtail, whinchat, and corncrake populations—species that need wild grasses and meadows to thrive. The population of sparrows, which have been so common in Moscow, has also seen a dramatic decline due to the lack of food in the freshly mown grass during the nesting period.

At the same time, 2017 polls conducted by the Biology Department of MSU, together with the Online Market Intelligence research organization, showed that 46% of Moscow residents preferred natural landscapes as opposed to 16% who reported to prefer decorative landscapes. But it is no easy job to channel the actions planned by the city into preserving biodiversity. Taking this project as a reference, we have approached the authorities and tried suggesting another approach to landscaping that was hailed as important by the local community and a wide community of professionals.

From “barren Land” to people’s favorite meadow

Before getting a locally known nickname—the Cherished Meadow—this place had been dubbed “barren land”. Once this three-hectare plot housed car sheds that were later pulled down, followed by repairs of underground pipes. And when in the summer of 2016 the repairs were finally complete, the natural growth and wildlife began to slowly take over again. Nature was quickly entering the vacant niche, making use of seedbank left along the sidewalks and across barren land and of soil brought here for earthworks. Natural migrants also came: insects and spiders with aerial settlement routes, wind-borne seeds, also from nearest block’s yards, birds attracted by the food base. But nobody knew or studied the value of the place: a meadow strip lost among the houses did not draw people’s attention and turned into a shelter for birds and insects.

This state of things endured until 2017 when the local administration came up with an idea to build a park there. The project featured sports-grounds and children’s playgrounds. Everything would have been neat but for the fact that, a year before exactly, an identical park had been opened across the street. Furthermore, a project with such a high recreational burden implied asphalting off over 40% of the natural territory. In line with the latest trends in Moscow greening efforts, wild grasses were to be replaced with lawns and flower pots were to be planted with species considered invasive for the city, such as cogon grass (which behaves aggressively in moderate climate, overtaking natural communities and spreading easily) and silvergrass (which does not live long in such weather conditions).

It was by mere coincidence that I learnt about the project as it was being prepared and I made a case before the head of the administration: residents should be given a chance to suggest a project of their own. And if many people and local authorities appreciate the project, then the funds initially allocated for the municipal administration project would be used to finance the residents’ project. My idea was supported by the newly elected district municipal officials, and one of them, Irina Dontsova, became the project’s co-coordinator. From then on, we only had to find and engage design specialists. It seemed impossible in the beginning: without financing, with only an idea and mere enthusiasm in hand.

But looking back, we understand that the Cherished Meadow project brought together a unique team: never before has our country (or many other countries either) seen projects developed in an interdisciplinary cooperation on an equal basis with the help of biologists, architects, landscape architects, and the involvement of residents and local authorities.

Ways of finding professionals who think alike to develop a project

I believe in being direct. Just imagine: I contacted and asked for help not just someone who is a biologist, but I did so with brilliant scientists who developed the Red List of Moscow: Liudmila Volkova and Nikolay Sobolev. It was they who suggested inviting the entomologist and the specialist on wild bees Timofey Levchenko, who was appointed the chief researcher for the meadow. A meticulous study of the area by biologists showed that it was inhabited by more than 500 species of animals, plants, and mushrooms. There were found 19 species included in the Moscow Red List (adopted in VII.2019). Out of them meadow grassy plants accounted for over 100 species. Forest grasses – for 30 species. Fauna was represented by over 300 species out of which birds accounted for 21 species. All of this, had it not been for the job biologists did, could be simply destroyed by the design that did not take into account the specific biological features of the territory. This 3 ha wild natural meadow is unique for the 844 ha Academichesky district of Moscow—this territory remains the only one here that has not been landscaped.

At the same time, Irina Dontsova contacted the department of landscape architecture in Moscow Institute of Architecture where she had once studied. Ekaterina Prokofieva, head of the department, not only suggested for the project Anna Antokhina and Nadezhda Astanina, great architects and “Gardens and People” Award Laureates, but also proposed to personally lead this ambitious project. All of us, without making any preliminary arrangement, as if decided to some extent to prove that another approach to designing public spaces was possible, that is, environment-oriented.

Communicating with residents

We decided to talk to residents first. We were lucky: the Akademichesky district has quite a big community Facebook group, with about 4-5 thousand participants, so it is rather easy to urge the most active residents to discuss the situation.

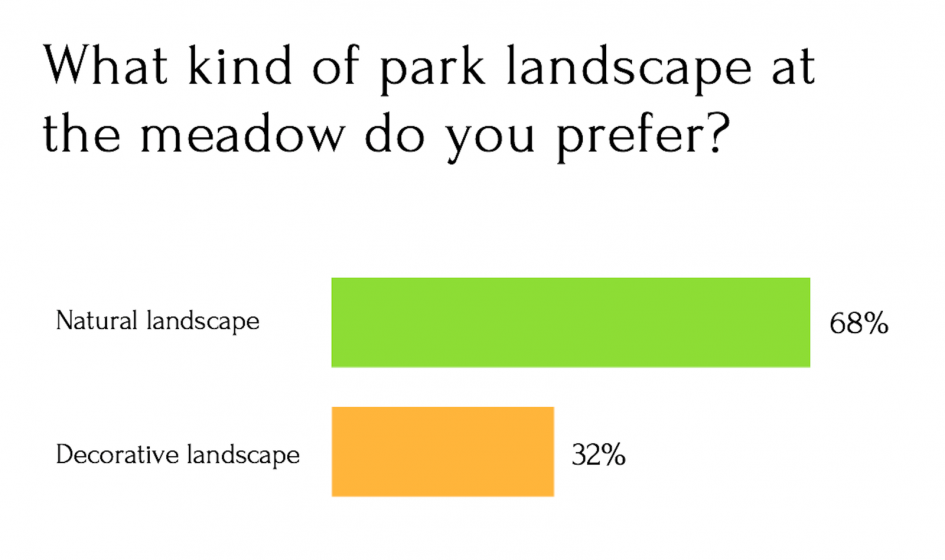

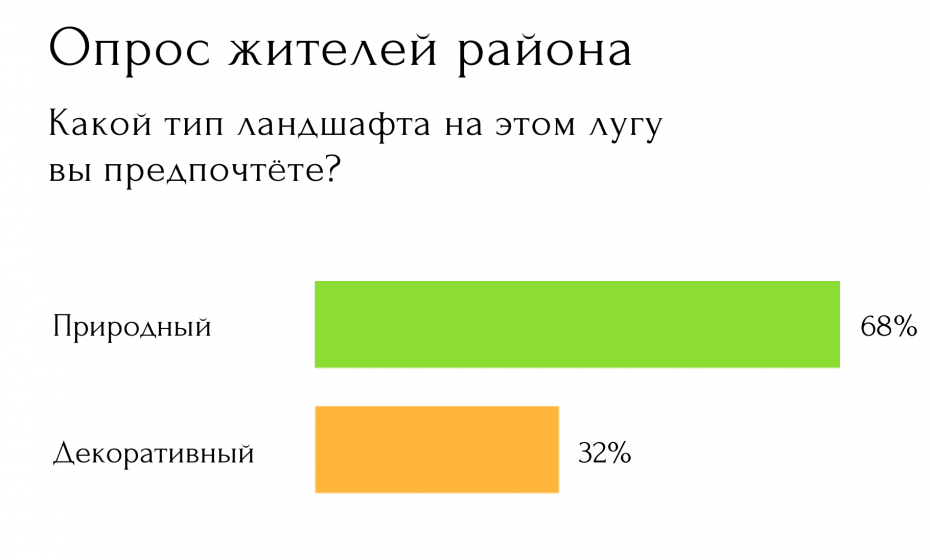

In addition to that, I launched a poll in Google forms and sent it to everybody willing to take part in order to gather a more objective feedback on what district residents wanted this territory to look like. Almost 70% responded they wanted a natural area, the one where no lawns were mowed, and where meadows and forest grasses grew.

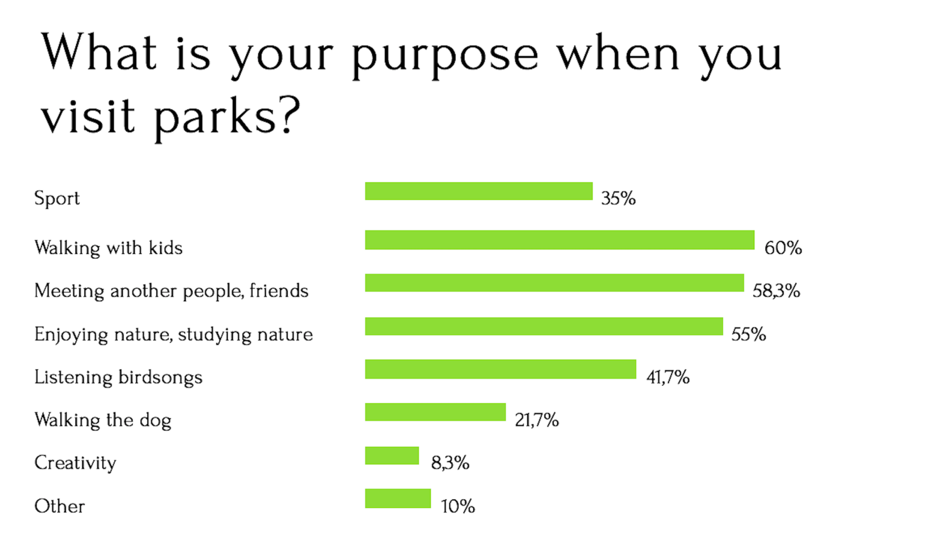

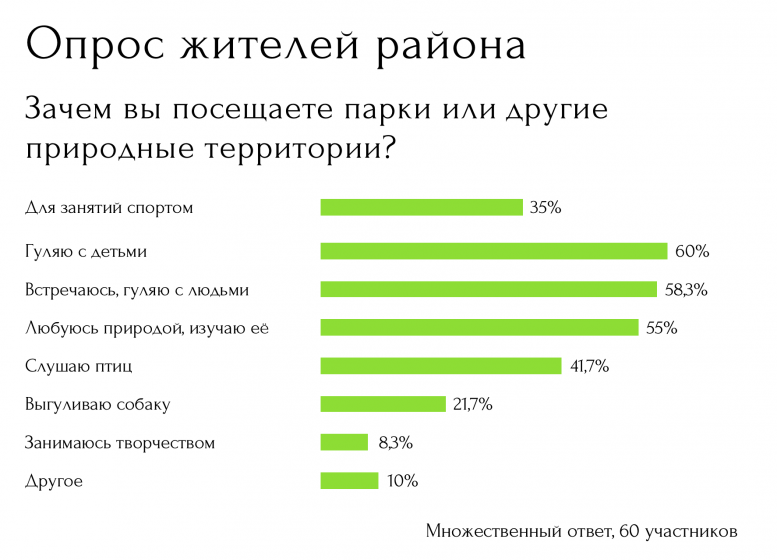

The three main reasons cited in response to the question “Why do you go to parks?” were: walking with children; meeting other people; and having the possibility to admire and watch nature. 40% of respondents come specifically to listen to the birds sing.

The three main reasons cited in response to the question “Why do you go to parks?” were: walking with children; meeting other people; and having the possibility to admire and watch nature. 40% of respondents come specifically to listen to the birds sing.

The three most popular ideas (that got over 50% of votes) for our project were:

- Planting a larger number of beautiful meadow grasses and flowers

- Creating conditions for rare species

- Providing a sheltered habitat for the nesting birds

But, notwithstanding the seeming unanimity and the wish expressed by the majority to go with the natural format, the community became divided by a huge conflict. Residents who lived in the houses adjacent to the meadow were complaining of the drastic shortage of parking spaces. The yard had a dead end, and they simply were not able to pass one another without that additional space. Tensions were so high that a resident of one of the houses demanded that the meadow should only be left on the margin of the territory and everything else should be asphalted; he even calculated that an estimate of 2,000 parking places could be built. Fortunately, his suggestion did not get any support.

Running a bit ahead of the story, I can say that the architects managed to take every view into account, and car owners got their parking space. Only it turned out that, with careful calculation and planning in the field, the number of the necessary parking places was far from 2,000, but in reality was as low as 70. Besides, the professional approach of placing parking lots at the margins of the meadow, and not in the center, as had been initially planned by the administration, solved the issue of risky fragmentation of meadow areas and inevitable degradation of the species composition that would have resulted.

For me personally, communicating with residents turned out to be one of the most challenging jobs within the project. In order for the people to trust the team, for them to feel involved, and to understand the whole process, we had to inform them of every move: what we were doing, with whom we were meeting, and what progress was achieved. At that point I was posting endless reports in district communities, and a year later we created a Facebook page exclusively dedicated to the meadow.

From proper planning to adequate design

Biologists imposed rigorous terms of reference, and in order to take them into account the team of architects often had to develop new rules and literally establish new standards in park design.

Ideas and solutions:

- It was decided to rule out lawns. Because there are many sport objects with lawn across the street. Our project was fully based on wild meadow grasses. The lawn is not a place where insects can survive or where birds can feed. On the contrary, various meadow plants with beautiful flowers provide food for pollinators, i.e., wild bees, butterflies, etc.

- It was decided that after completing construction, only plants native to the Middle part of the East European Plain would be used both for flower beds and for the replanting in the soil, in order to rule out aggressive proliferation of invasive species and consequent destruction of the meadow community. This was a challenge for two reasons. Firstly, due to the lack of demand for local species in landscape design. It was a challenge in its own right to find the “common” species which would be available for sale. Secondly, biologists and architects had to find through joint efforts a balance between “native” and “quite decorative.” This list of native plants for creating a meadow as a beautiful park was a really unique case of interdisciplinary collaboration: the biologist suggested what was better for the insects and the landscape architect chose the most beautiful plants from that list that would be surely appreciated by humans as well.

- To create better conditions for species that are considered rare or near threatened in Moscow. For instance, a nightingale builds its nest on the ground and it needs bushes and tall grass for successful nesting period. We decided to plant some additional bushes in the area where we knew nightingales nested. Also, we took into account needs of wild bees: for example, the list of grasses to plant on the meadow was tailored in a way to create richer forage for wool carder bee (Anthidium florentinum) and other other rare types of bees.

- The territory had a wet area. It was decided to turn this “drawback” into an advantage by planting it with beautiful, moisture-loving species. Thus, this area was converted into the highlight of the meadow, and architects designed a small viewpoint here.

- Paths convenient not only for the pedestrians, but also for the insects! Here, the architects had to come up with a know-how technique: not only did they make a pavement without edging, but they also introduced narrow galleted joints (pebbles places in the morter). They are almost unnoticeable for people, but they are very important for small insects: they will be able to use them as corridors to go from one place to another. Because not every insect can fly, and for some species asphalted paths with edging can be an insurmountable obstacle.

- It was suggested to use UV-free lamps so that insects would not be attracted to them, would not get burned die.

On top of that, we provided for a children’s playground made of natural materials in “natural style, and other small recreation areas thought-out to the last detail.

“We tried to think about everyone who lives in this area or in the vicinity: people, birds, other animals, and plants. To strike a balance between urbanism and nature’s interests. This also corresponds to our own needs: we want nature back in the city because it is responsible for the comfort of the environment where we live, for our general emotional background, leisure, and stress resistance.”

— Anna Antokhina, architect.“This is currently a very popular world trend in city landscape architecture, and we are hoping it will eventually come to Moscow as well: people return to nature, and the greening efforts are exclusively about planting species native to a territory. And we decided to make our own contribution to this return.”

— Nadezhda Astanina, landscape architect and co-author of the project.

As a result, everything was ready by the set deadline: drawings, detailed technical description, sketches based on the geologic and topographic report, and model layout of the territory. Max Vorotnikov, one of the district residents, did a beautiful visualization or rendering of the project.

Our presentation got roaring applause. Everybody appreciated the project. But, most importantly, we managed to reduce landscaping and subsequent asphalting off of the area to 16% of the territory (the other 84% being left as a green area) rather than 40%, as was initially planned by the administration. We succeeded in decreasing the estimated cost of the project from approximately 56 to 46 million roubles (from $US823,000 to $US676,000), making it at the same time more tailored to the residents’ wishes. As a result, over 3,000 people signed in favor of the project.

It was eighteen months ago. Since then the project:

- has been given as many as two architecture awards

- has been approved by the scientific community, flora and fauna have been studied here for the last two years

- has been supported by the Council of District MPs and by local authorities

- has been followed by the media, including the federal television

- has been dubbed meadow by residents with the word “cherished”, rather than “barren land”.

Attention to and accountability for this place have been steadily growing: we have already conducted two clean-up events here in spring and picked litter together with the residents. Every time no less than 30-40 people took part, including people from other city districts.

The project implementation is planned for 2021-2023 at the expense of the city budget. And while there is no park here yet, we have agreed with local authorities on a special regime of maintenance for this territory. This summer the meadow was officially granted the wild grass area status, and in practice this means that the grass will be mowed no more than twice a season (more frequent mowing will only be done near the paths that people use). But it is not the whole meadow that will be mowed: every year the mowed stripes will be alternated as in a patchwork. This will, on the one hand, protect the meadow from the extensive growth of bushes and trees and, on the other hand, ensure the height of grass needed for insects and birds to feed and breed.

Nadezhda Kiyatkina

Moscow

* * *

Как вдохновить жителей, специалистов и чиновников создать проект парка, поддерживающий биоразнообразие

Мы спрашивали жителей, чего бы они хотели. И мы старались думать обо всех, кто живет в этом районе или поблизости: о людях, птицах, других животных и растениях – чтобы найти баланс между урбанистикой и природой.

В последние два года наша междисциплинарная команда работает над проектом парка «Заповедный луг» – уникальность его в том, что это первый за многие годы проект городского парка в Москве, созданный для сохранения экосистемы, а не для развлечений. Проект возник как общественная инициатива, без финансирования. Совместная работа биологов, ландшафтных архитекторов, архитекторов, муниципальных депутатов и жителей позволила создать проект, одинаково отвечающим интересам природы и людей.

Контекст

В последние семь лет в городских парках развернулись масштабные работы по благоустройству: больше 500 природных территорий города частично или полностью подверглись перепланировке, стали более «урбанизированными», в них появилось больше мест для активного отдыха. Взамен разнотравья создаются рулонные или стриженные газоны, убирается прошлогодняя листва, грунтовые дорожки заменяются на плитку, а в озеленении активно используются агрессивные инвазивные виды, хоть и красиво цветущие. Ассортимент видов растений никак не учитывает влияние, в том числе негативное, на местные экосистемы. На эти работы из бюджета Москвы потрачено уже больше 50 млрд рублей.

Цель государственной программы – придать природным территориям более «декоративный» вид, сделать отдых москвичей, по мнению властей, более комфортным. В то же время в следствие этих работ, по данным программы «Птицы Москвы и Подмосковья», Зоомузея МГУ и биологического факультета МГУ, в столице сильно сократилась численность соловьев, желтой и желтоголовой трясогузки, лугового чекана, коростеля – этим видам для успешного существования нужно разнотравье и луга. Резко упала численность воробьев, обычной для Москвы птицы, так как перестало хватать корма в гнездовой период из-за стрижки травы.

При этом опросы, проведенные на биофаке МГУ в 2017 году при участии исследовательской компании OnlineMarket Intelligence, показали, что 46% москвичей предпочитают природный ландшафт, в то время как декоративный – только 16%. Но развернуть запланированные городом работы в русло сохранения биоразнообразия не так-то просто. На примере нашего проекта мы попробовали предложить властям другой подход к благоустройству и нашли большой отклик среди местного сообщества и широкого круга профессионалов.

Из «пустыря» – в любимый жителями луг

До того, как превратиться у всех в районе на слуху в «Заповедный луг», люди называли это место «пустырем». Когда-то здесь, на участке площадью в 3 га, были гаражи, потом их снесли, вели ремонт коммуникаций. И когда наконец закончили, летом 2016 года, здесь начала восстанавливаться естественная растительность и животный мир. Природа очень быстро заполняла свободную «нишу», используя «резервы» семян, оставшиеся по обочинам и пустырям, а также из завезенного сюда грунта в результате земляных работ. Попадали сюда и «естественные переселенцы» – расселяющиеся по воздуху насекомые и пауки, разносимые ветром семена, в том числе, с близлежащих дворов, привлеченные кормовой базой птицы. Но о ценности этого места никто не знал, никто не исследовал – затерянная между домами полоска луга не привлекала внимания людей и стала убежищем для птиц и насекомых.

Луг, август 2018. Фото Тимофея Левенко.

Луг, июнь 2019. Фото Алексея Денисова.

Так продолжалось до тех пор, пока в 2017 году местная управа не задумала сделать здесь парк. В проекте планировались спортивные и детские площадки, и все бы ничего, но ровно год назад через дорогу открыли такой же. Кроме того, проект с такой высокой рекреационной нагрузкой предполагал запечатывание больше 40% естественной территории. Согласно последним тенденциям в московском озеленении, тут планировали заменить разнотравье на газоны, а на клумбах использовать инвазивные для города виды – такие как императа цилиндрическая (которая в условиях нашей средней полосы ведет себя как агрессивный вид, внедряющийся в природные сообщества и легко расселяющийся) и мискантус (особо не выживающий в наших условиях).

Проект Управы Академического района г. Москвы, 2017 год.

Я узнала о готовящемся проекте случайно – и обратилась к главе управы с просьбой: дать шанс жителям представить свой проект. И если он понравится большому числу людей и местным властям, то выделенные на проект Управы деньги пойдут на проект жителей. Мою идею поддержали только что избравшиеся районные муниципальные депутаты, а одна из них – Ирина Донцова – стала сокоординатором проекта. Оставалось только найти и привлечь специалистов на проектирование. Сначала это казалось нереальным – без финансирования, на идее и энтузиазме. Но оглядываясь назад, мы понимаем, что «Заповедный луг» объединил уникальную команду: никогда еще в нашей стране (как и во многих других странах) проекты не создавались в равном междисциплинарном диалоге между биологами, архитекторами и ландшафтными архитекторами, в диалоге с жителями и местными властями.

Как искать профессионалов-единомышленников для создания проекта

Главный и единственный совет – не нужно бояться просить людей поделиться своей экспертизой pro bono. Не для всех деньги – наивысшая ценность. Кому-то будет интересно принять участие в проекте, потому что совпадают ценности, а кому-то захочется выйти за пределы рутины.

Я наглая. Потому что написала с просьбой помочь не просто биологам, а блестящим ученым, составителям Красной книги Москвы – Людмиле Волковой и Николаю Соболеву. Они же посоветовали привлечь специалиста по диким пчелам, энтомолога Тимофея Левченко, который стал главным исследователем луга. Тщательное исследование биологами участка показало, что здесь более 500 видов животных, растений и грибов. Зафиксировано 19 видов Красного списка города Москвы (принят в VII.2019). Травянистые растения лугов – более 100 видов. Лесные травы – 30 видов. Фауна – более 300 видов, из которых птицы – 21 вид. Все это, не будь проведена работа биологами, могло бы быть просто уничтожено проектированием без учета биологических особенностей местности.

Некоторые виды из Красной Книги Москвы (2019) на «Заповедном лугу» (слева направо и сверху вниз): медуница неясная (Pulmonaria obscura), колокольчик раскидистый (Campanula patula), дремлик широколистный (Epipactis helleborine), кобылка большая болотная (Stethophyma grossum), шмель садовый (Bombus hortorum), бронзовка золотистая (Cetonia aurata). Фото Тимофея Левченко.

Некоторые бабочки «Заповедного луга» (слева направо и сверху вниз): голубянка икар (Polyommatus icarus) самец, голубянка горошковая (Cupido argiades), павлиний глаз (Aglais io), голубянка икар (Polyommatus icarus) самка, перламутровка адиппа (Argynnis adippe), крапивница (Aglais urticae). Голубянка горошковая и перламутровка адиппа в Красной Книге Москвы (2019). Фото Тимофея Левченко.

Параллельно Ирина Донцова обратилась на кафедру ландшафтной архитектуры МАРХИ, где когда-то проходила обучение. Руководитель кафедры Екатерина Прокофьева не только посоветовала замечательных архитекторов для проекта – лауреатов премии «Сады и люди» Анну Антохину и Надежду Астанину, но и вызвалась лично курировать амбициозный проект. Все мы не сговариваясь как будто решили доказать, что может быть совершенно другой подход в проектировании общественных пространств – экологоориентированный.

Команда проекта (слева направо и сверху вниз): архитекторы и ландшафтные архитекторы Екатерина Прокофьева, Надежда Астанина, Анна Антохина; координаторы проекта и местные жители Ирина Донцова, Надежда Кияткина, дизайнер Максим Воротников; биологи Николай Соболев, Людмила Волкова, Тимофей Левченко

Коммуникация с жителями

Мы решили начать дело с обсуждения с жителями. Нам повезло: в Академическом районе довольно большие районные группы в Фейсбуке – в них состоит около 4-5 тысяч участников, поэтому к обсуждению ситуации довольно просто привлечь активную часть жителей.

Отдельно я запустила опрос, создав его на Google-формах и разослав по желающим, чтобы собрать более объективный фидбек, какой же хотели бы видеть эту территорию жители района. Почти 70% ответили, что природной — где не стригут газоны, растут луговые и лесные травы.

Источник: онлайн-опрос жителей Академического района Москвы на Google Forms, 60 участников. Осень 2017 г.

Источник: онлайн-опрос жителей Академического района Москвы на Google Forms, 60 участников. Осень 2017.

На вопрос «Зачем вы посещаете парки?» тремя главными причинами люди назвали: прогулки с детьми, встречи с другими людьми и возможность любоваться природой, наблюдать ее. 40% целенаправленно приходят послушать пение птиц.

Тремя самыми популярными идеями в рамках проекта (за них высказались больше 50% жителей), оказались:

- Высадить больше красивых луговых трав и цветов

- Создать условия для редких видов

- Создать места-убежища для гнездования птиц

Но несмотря на кажущееся единодушие и желание большинства природной концепции, в сообществе оказался большой конфликт. Жители домов, которые прилегают непосредственно к лугу, жаловались, что им очень не хватает парковок. Двор заканчивается тупиком, и машины просто не могут разъезжаться. Эмоции были настолько сильными, что житель одного из домов требовал оставить луг по краю территории, а остальное заасфальтировать: посчитал, что получится 2000 парковочных мест. К счастью, его не поддержали.

Забегая вперед, хочу сказать, что у архитекторов получилось учесть мнение всех, и автомобилисты получили парковки. Только, как оказалось, если выйти на местность, все грамотно посчитать и спланировать, требуется далеко не 2000 парковочных мест, а 70. Кроме того, грамотная планировка парковок по краю луга, без выноса их в центр, как в изначальном проекте Управы, решала вопрос риска фрагментации луговых участков и дальнейшее неизбежное обеднение видового состава.

Коммуникация с жителями для меня вообще оказалась одной из самых сложных работ в рамках этого проекта. Чтобы у людей было высокое доверие к работе, они чувствовали себя вовлеченными и понимали весь процесс, пришлось информировать о каждом шаге: что делаем, с кем встречаемся, какой прогресс. Я на том этапе бесконечно писала посты в районные группы, спустя год мы создали свою страницу луга в Фейсбуке.

От правильного планирования – к грамотному проектированию

Биологи дали строгие вводные – и часто, чтобы учесть их, команде архитекторов приходилось вырабатывать новые стандарты в подходе к проектированию парков.

Идеи и решения:

- Отказались от газонов. Сделали проект полностью на луговом разнотравье. Газон не дает возможности выживать насекомым и кормиться птицам. А на разнообразных луговых растениях с красивыми цветками могут кормиться опылители – дикие пчёлы, бабочки и другие.

- После строительных работ как для восстановления луговых участков, так и для клумб выбирать растения, произрастающие только в нашем регионе, чтобы исключить агрессивное распространение инвазивных видов и как следствие угнетение естественного лугового сообщества. Это само по себе было большим вызовом. Во-первых, из-за отсутствия спроса на местные виды в ландшафтном дизайне. Нет спроса – нет предложения. Во-вторых, биологи и архитекторы должны были совместными усилиями найти баланс между «родным» и «довольно декоративным». В итоге получился не только уникальный список красивых цветущих трав, но и сам процесс работы над ним стал примером редчайшего междисциплинарного диалога: биолог предлагал, что лучше для насекомых, и ландшафтный архитектор выбирал из этого списка самые красивые растения, которые наверняка оценят и люди.

- Создать лучше условия для видов, которые считаются редкими или требующими внимания в Москве. Например, соловей строит свое гнездо на земле, и для успешного гнездования ему нужна высокая трава и кустарники. Решили нанести на план несколько дополнительных кустов в той части луга, где, как мы знали, гнездились соловьи. Также учли потребности диких пчел: например, список трав для посадки на лугу был составлен таким образом, чтобы создать более богатую среду для шерстобита флорентийского (Anthidium florentinum) и других редких видов пчел.

- На участке была сырая зона. Решили сделать этот «недостаток» преимуществом – высадить здесь красивые растения, любящие влагу. Так это место превратилось в акцентную точку луга, архитекторы спланировали тут небольшую смотровую площадку.

- Дорожки, удобные не только для пешеходов, но и для насекомых. Тут архитекторам пришлось разработать ноу-хау: сделать тротуар не только без бордюров, но и предусмотреть между плитками небольшие расклиновочные швы. Они почти незаметны человеку, но важны для мелких насекомых – по ним они смогут передвигаться как по коридорам. Ведь не всякое насекомое может летать и для отдельных видов асфальтированные дорожки с бордюрами становятся непреодолимой преградой.

- Светильники предложили использовать без ультрафиолета, чтобы насекомые не летели на них, не обжигались и не гибли.

И это не считая детской площадки из натуральных материалов, выполненной в «бионическом» стиле, и других, продуманных до мелочей, небольших зон отдыха.

«Мы постарались позаботиться обо всех, кто живет в этой местности или около нее: людях, птицах, других животных, растениях. Соблюсти баланс между урбанистикой и интересами природы. Ведь это и в наших интересах: природа должна вернуться в город, потому что от нее зависит и комфортность среды обитания, и общий эмоциональный фон, и наш отдых, и стрессоустойчивость», — говорит архитектор Анна Антохина.

«Сейчас это очень популярная мировая тенденция в городской ландшафтной архитектуре, и мы надеемся, что она придет и в Москву, — люди возвращаются к природе, а в озеленении используются исключительно родные для местности растения. И мы решили внести свой вклад в это возвращение», — дополняет соавтор проекта, архитектор Надежда Астанина.

В итоге, к назначенному сроку проект был готов – эскиз, подробное техническое описание, чертежи на основе геоподосновы, и макет территории. Красивую визуализацию проекта сделал житель района Макс Воротников.

Проект «Заповедный луг», февраль 2018. Визуализация Максима Воротникова

На презентации мы сорвали овации. Проект понравился всем. Но главное, удалось сделать так, что благоустройство и как следствие запечатывание пространства затронет только 16% территории, а не 40%, как планировала изначально управа. Остальные 84% – зеленая зона. Ориентировочную стоимость проекта удалось снизить примерно с 56 до 46 миллионов рублей, при этом приблизив его к желаниям жителей. В результате за проект поставили свои подписи больше 3000 человек.

Презентация проекта, февраль 2018. Фото Александра Кияткина.

С тех пор прошло 1,5 года.

– проект взял уже две архитектурные премии

– одобрен научным сообществом, в течение двух лет здесь ведется изучение флоры и фауны

– поддержан советом депутатов района и местными властями

– за проектом следят СМИ, включая федеральное ТВ

– жители называют его не «пустырем», а лугом. Добавляя «заповедный».

Растут внимание и чувство ответственности за это место: мы провели здесь уже два субботника по весне для жителей – вместе убирали мусор. И каждый раз в нем принимали участие не меньше 30-40 человек, в том числе, из других районов города.

Субботник на лугу, 2019. Фото Веры Кочиной.

Пока здесь еще нет парка, мы договорились с местными властями об особом режиме содержания этой территории. Этим летом лугу присвоили официальный статус разнотравного участка, и это значит, что косить его будут не больше двух раз за сезон (чаще можно стричь только у тропинок, по которым ходят жители). Но не целиком, а мозаично, каждый год чередуя скошенные полосы. Это позволит, с одной стороны, не дать зарасти лугу кустарником и деревьями, а с другой – оставлять высокую траву для питания и размножения насекомых и птиц.

Надежда Кияткина

Москва

Надежда Кияткина, инициатор проекта «Заповедный луг», член Союза охраны птиц

Leave a Reply