Humanity will not and should not abandon our cities because of coronavirus. Rather, we should view this horrible pandemic as a spur to improve upon, to make universal, and to include nature in humanity’s amazing invention of the Sanitary City.

We think the rumors of the impending demise of the city due to fear of pandemic have been greatly exaggerated. Cities have adapted to and overcome far worse disease outbreaks than this one over the centuries, by adopting “sanitary”, public health practices. Population density, per se, of a city is not strongly correlated with how rapid the spread of Covid-19 has been, and some dense cities have managed the disease well. Finally, the response of cities to Covid-19 should involve an expansion of the Sanitary City, not a retreat from it, and should include increasing investment in urban greenspaces.

The Sanitary City helps limit disease outbreaks

Cities put people in proximity to one another, speeding up interaction and boosting economic vitality, making them what one scholar called humanity’s greatest invention. However, urban settlements can help spread infectious diseases, if the conditions are right. Up through the 19th century, cities were relatively unhealthy places to be compared to rural areas, at least in terms of infectious diseases. As a result, people lived shorter lives in cities; a pattern urban demographers refer to as the “urban health penalty”. Shorter lifespans were caused primarily by poor nutrition among the urban poor and outbreaks from infectious diseases like cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis, which killed thousands in cities each year. Yet people were attracted to the economic opportunities cities offered despite the urban health penalty, and overall urban population growth continued.

All of that is ancient history. The good news is that, since the 20th century, cities have mostly solved the urban health penalty. Urban areas are now on average healthier places to be than rural areas, in both the Global North and the Global South. In part this is because (in most years, in most places) infectious diseases no longer spread unchecked. Cities did this by creating what one historian called the “Sanitary City”. Rising standards of living and cheaper food improved the poor’s access to nutrition. At the same time, municipal governments (now aware of the germ theory of disease) began to create systems to deliver clean drinking water to their residents, as well as sanitary sewer systems. Cities made efforts to clean up their air quality, at least locally, by banning certain kinds of burning (e.g., coal for domestic use). Governments created public health systems and hospitals to treat those who did get sick. This enormously complicated transition (we are simplifying here) ultimately eliminated the urban health penalty in many places. Where these innovations of the Sanitary City have still not reached urban communities, as in the informal “slum” settlements of the Global South (or indeed, in homeless encampments in the Global North), the threat of infectious disease remains.

Given this history, we are skeptical that cities will be abandoned because of this pandemic. At the height of the urban health penalty in the 18th and 19th century, the death rate in London was often 50% higher than the national average (orders of magnitude higher morality impacts than Covid-19 will ever cause). Yet the city was not abandoned, but instead grew in population almost seven-fold. Globally, rapid urban growth has continued and will continue for the next several decades. With the invention of the Sanitary City, our cities are on average healthy places, and the trajectory of urban growth has advanced despite the occasional epidemic. The growth of cities wasn’t slowed after the 1918 Spanish Flu (of which an estimated 50 million died globally), nor after the 1957 (>1 million deaths) or 1968 flu pandemics (>1 million deaths). Cities have survived pandemics in the 20th century that were hundreds of times more lethal than the current outbreak has been to date. The organization of human society into urban agglomerations is robust and will likely continue.

Don’t blame density

In addition to predicting an exodus from cities, commentators have also pointed to urban density as the “enemy”, arguing that because rural areas may make it easier to social distance, they would likely see less rapid spread. But over the past few weeks, the pandemic has spread to more and more rural areas around the world, and there is little evidence that density per se is exacerbating spread of Covid-19. Available fine-scale global data is not complete enough for a statistical analysis, but a review of news reports finds little consistency. While New York City is dense (average density in metro area, 2000 people/km2) and struggling to contain the virus, Hong Kong (average density 6300 people/km2) and Seoul (16,000 people/km2) are significantly denser and have done quite well in containing the virus. A better predictor of how well cities have done at containing Covid-19 is the rapidity and strength of their public health responses, both within municipalities and nationally. Other factors, such as the per capita availability of hospital beds, and access to good healthcare, may also ultimately be more important than the density of the community where you live.

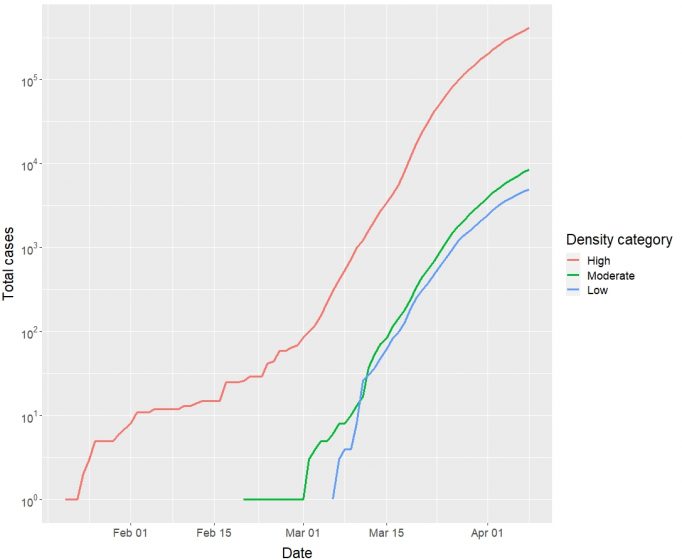

Similarly, in the US there is, at best, a weak relationship between density and spread of Covid-19. Here the data is complete enough to allow some analysis. We took data from the New York Times database of cases at the county-level, and divided counties into three categories based on their population density: Low Density (0.05 – 25 people/mi2), Moderate Density (25 – 60 people/mi2), and High Density (>60 people/mi2). These data show that high density counties in the United States (mostly urban areas) were the first to see cases, likely due to their connections with the outside world. Because of the earlier timing of outbreaks, the number of cases is greatest in these big metro areas. However, as the virus has spread into smaller cities and more rural communities, the spread of coronavirus appears to be just as rapid there.

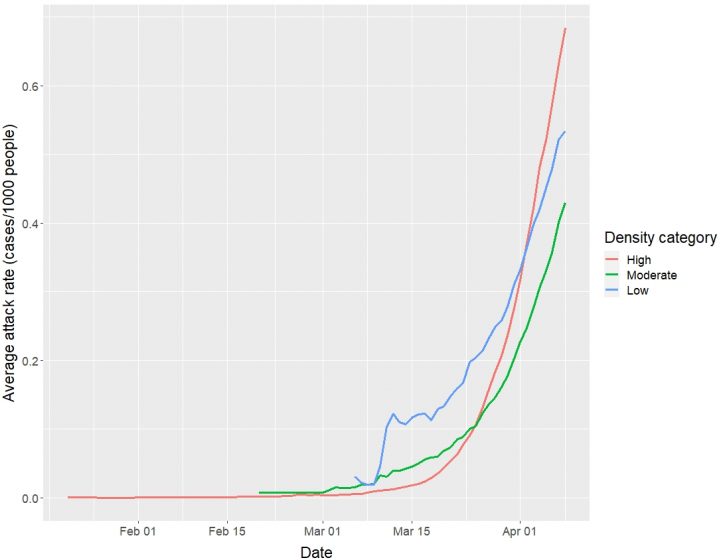

Most cases are in high-density counties with large urbanized populations. This is not surprising, since that is where most people live in the United States! There are 292 million people living in high-density counties, 21 million in moderate-density counties, and only 11 million living in low-density counties. An arguably more meaningful measure of the risk to a community is the attack rate, the number of cases of coronavirus per 1000 residents.

Viewed this way, the trends look different. Tracking outbreaks over time, we can see that the virus first appeared in high-density counties, then in moderate-density counties, and arrived last in low-density counties. However, the attack rate has not been consistently highest in high-density counties. Furthermore, while high density counties appear to have overtaken lower density counties (at least for the moment), the difference in attack rate is less than a factor of two, despite vast differences in population density. For reference, high density counties have a 28% higher attack rate than moderate density counties (0.68 vs. 0.53 cases/1000 people) and a 61% higher attack rate than low density counties (0.68 vs. 0.42 cases/1000 people). In other words, if you encounter someone at random, the risk of them having coronavirus is only slightly lower in low density counties than in moderate or high-density counties.

The Sanitary City after Covid-19

This history of the invention of the Sanitary City is helpful as we think about the spread of Covid-19. The modern city was designed to prevent the spread of waterborne illness, and it does a remarkably effective job at that. Diseases that are spread by airborne, person to person contact like Covid-19 can still spread in cities, although public health systems and hospitals can help treat the disease and slow its spread. What then is the likely response of cities to the Covid-19 pandemic, over the long term? We argue it will not be a wholesale abandonment of cities, but instead some subtle changes in urban form and function.

For the public sector, the response will likely look a lot like a continuation of the “sanitary”, public health response cities have taken following other infectious disease outbreaks. Cities may work to strengthen universal access to clean water and sanitation, especially among populations like the homeless or those in informal settlements in the Global South. Public health systems may work to ensure greater access to medical care for all citizens, especially lower income or minority populations that currently are being hit harder by Covid-19. There may also be greater epidemiological surveillance of urban populations so outbreaks can be dealt with early, which new technology allowing the identification of outbreaks faster (while also potentially raising privacy concerns).

The form of metro areas may also change somewhat, as the great experiment with teleworking during Covid-19 accelerates a trend that was already occurring, with employers offering more flexibility for teleworking for white-collar workers. The experience of the pandemic may also accelerate a trend toward “hoteling”, as companies maintain centralized places to meet and allow for person, face-to-face interaction, but shrink their offices and reduce their rent by assuming a greater fraction of their workers will telework on any given day. But research has clearly shown that the Internet and personal, face-to-face interactions are complementary goods, not substitutions. While Covid-19 may make us more comfortable doing many meetings online, humans will still want and need to interact in person during critical work periods.

Increased investment in urban nature may be another response that expands the Sanitary City. As millions of urban residents adjust to life under shelter-in-place orders, having access to urban greenspaces for fresh air and exercise has become ever more essential. Providing accessible and equitably distributed greenspaces is being discussed now to facilitate outdoor recreation during a pandemic. If this greenspace expansion occurs, it would also support biodiversity, reduce urban temperatures, and provide the mental health benefits of nature access. Using greenspace designs that reduce transmission during pandemics could also bring along other benefits. For example, designing greenways wide enough to promote social distancing, and connecting urban parks to one another using greenways could enable cooped up urban residents’ greater access to nature during pandemics. These same design elements would also support the movement of wildlife, plants, and people during a post-pandemic world.

Urban form has changed over the centuries, both to make the Sanitary City and in response to changes in transportation and other technologies. We hope changes to urban form motivated by the pandemic will allow for greater access and more equitable distribution of nature in cities. Humanity will not and should not abandon our cities because of coronavirus. Rather, we should view this horrible pandemic as a spur to improve upon, to make universal, and to include nature as part of humanity’s amazing invention of the Sanitary City.

Robert McDonald and Erica Spotswood

Washington and Oakland

This essay represents the views of the authors and not necessarily those of their employers, The Nature Conservancy and the San Francisco Estuary Institute.

about the writer

Erica Spotswood

Dr. Erica Spotswood is a Senior Scientist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute. Her work creates tools and approaches for bringing scientific information into the planning and design of urban nature. Current projects address how regional planning can integrate with local project-scale design, and how urban greening efforts can be coordinated to contribute to broader regional goals for biodiversity and climate resilience.

Leave a Reply