Urban development in the Amazon region could be reframed by associating two different systems of thought and practices: natural indigenous and technology capital production. Together—what I call a Third Landscape—they could meld “foreign” and “local” technologies within the relevance of local context.

1 Proposition

The logic of urban growth in the Brazilian Amazon could be changed if we succeeded in bringing together two different systems of thought and practices: that of the natural and indigenous, to that of technology and capital production. Together, they could guarantee the continued economic and environmental resilience of the region and pave the way to interesting hybrid solutions—what I have called a Third Landscape, where “foreign” and “local” technologies are employed within the relevance of local context. The Amazon could become a laboratory for design exploration, to establish a different logic for spatial (and maybe political) organization, where there is a productive encounter between natural and urban environments.

I have prepared a three-part article to expand on this idea. This one, where I lay out the proposition and try to justify it, a second one where through a series of images and short texts I interpret some of the ideas of what I have called a Circular Culture, that will serve as base for the understanding of an “indigenous imaginary”, and the last one where I make design propositions to exemplify what a Forest City could be.

2 Intro: extensive urbanization

In 1970, Henri Lefebvre posed the idea that the “total urbanization of society” was an inevitable process, which would demand new interpretive and perceptual approaches.[i] Indeed, not even fifty years later we are experiencing fast growing rates of urbanization, with more than half of the world’s population already living in urban centers. In many ways, it is not far different in the Brazilian Amazon. As consumption levels in our modern cities demand supplies from far-away sources, the Amazon region has been systematically integrated into the logic of urban growth with pressing global demand for its natural resources. Today, it is interconnected with Brazilian cities like São Paulo and Brasilia, as much as it is with other global cities like Tokyo, Montreal or Beijing. “Urbanization” has, in fact, arrived in the Amazon.

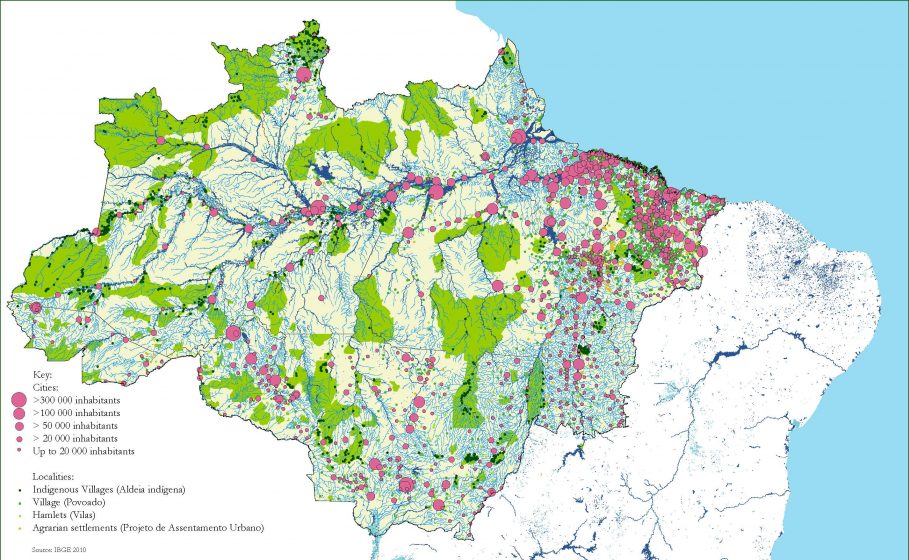

Within the logic of the extraction that regulates Amazonian economy, major deforestation factors such as farming, mining, largescale infrastructure, and logging are all supported by a network of towns and cities throughout the region. As Eduardo Brondizio points out in his article (https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2016/02/02/the-elephant-in-the-room-amazonian-cities-deserve-more-attention-in-climate-change-and-sustainability-discussions/), the Amazon urban net has grown quickly. There are more than three hundred cities with populations over twenty-five thousand people and an equal number of smaller cities in the Brazilian Amazon, in addition to scores of indigenous and small riverine traditional settlements. Today, the resiliency of the Amazonian biomes is very much intertwined with this web. As Thomas Lovejoy, “the Godfather of Biodiversity”, says: “It’s not simply about what happens in the forests; it’s also about what happens in cities. The quality of life in Amazon cities is a very important part of reaching the ideal solution.”[ii] (https://oglobo.globo.com/sociedade/conte-algo-que-nao-sei/thomas-lovejoy-biologo-ambientalista-preciso-criar-cidades-sustentaveis-na-amazonia-21829192)

However, despite the rich cultural and natural environments and the predominance of a decentralized pattern of small urban nuclei, urban settlements in the Amazon follow models that are totally foreign to their contexts, mirroring urban centers of the Brazilian Southeast, the US and Europe. There is widespread disregard for the forest and the traditional knowledge that comes with it. As Bertha Becker pointed out in 2013, “In this regional economy commanded from outside, indigenous culture and knowledge have mostly been dissociated from great transformation movements.”[iii]

But does it have to be this way?

No. But if we want to work within the realm of an ecological urbanism, we will have to acknowledge the strong interdependency between natural and urban environments. We will need to transition from a perpetual response to emergency, to a long-term vision that nevertheless is not standardized, but specific, interdependent and aligned with new technologies that are relevant to local context

3 Another Imaginary

One point of departure may be to look at the societies of the indigenous populations we have ignored in our rush to “progress”. If their paradigms are different from ours, maybe their solutions could enlighten us. But for that to happen we would have to acknowledge the possibility that modern society is not the only viable or credible social system and that economic progress and reliance on monetization are not “fundamental truths”.

Charles Taylor, in his book “Modern Social Imaginaries” coins the term “social imaginary” to explain the “intrinsic grasp” of our social environment and possibilities, pointing to the existence of a “moral order” that underlies our political and economic structures. In other words, our modern order is the one we may take for granted, or believe in, but it is not by any means the only possibility. Innumerous traditional communities, as well as disenfranchised ones, although imbedded in the reality of global economy, have found ways to live within different sets of values all over the world. Different imaginaries, or different “political imaginaries”, as Gibson-Graham have called them, are not fantasies or naïve discourse, but rather forms of alternative economic organizations that currently exist—“politics of possibilities” [iv] that locally define their own internal rules.

Castells pointed out in the 90s, that as the internet made the globalization of the production economy possible, it also created a platform for the connection of local voices.[v] Grounded in the reality of local possibilities and constraints, these voices can guide us in the conversation of what regional and global design could be. I have talked about this in another article at TNOC.

“The embrace of local power doesn’t have to mean parochialism, withdrawal, or intolerance, only a coherent foundation from which to navigate the larger world. From the wild coalitions of the global justice movement to the cowboys and environmentalists sitting down together there is an ease with difference that doesn’t need to be eliminated, a sense that . . . you can have an identity embedded in local circumstances and a role in the global dialogue. And that this dialogue exists in service of the local.” [vi]

As the deforestation of the Amazon poses a huge threat to our global environmental balance, indigenous populations have been able to sustain environmental preservation more efficiently than in other parts of the world. In Brazil, it is estimated that deforestation in indigenous areas can be substantially s smaller than in other non-indigenous lands, while in the world, indigenous land and communities are responsible for absorbing 37 billion tons of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. It is clear that indigenous cultural resilience and practices are tightly linked to the environmental resilience of their habitats.

My proposition is that we should examine traditional indigenous practices to inform our understanding of the urbanization occurring in the Amazon and explore the idea of a “hybrid urbanization” that is structured on alternative solutions arising from the encounter of two imaginaries—that of our modern world and that of the indigenous knowledge. I believe we could reframe the discussion of urban development in the Amazon region by associating two different systems of thought and practices: the natural and indigenous, to that of technology and capital production.

Together, they could guarantee the continued economic and environmental resilience of the region. This would pave the way to interesting hybrid solutions—what I have called a Third Landscape, where “foreign” and “local” technologies are employed within the relevance of local context. The Amazon has the potential to become a laboratory for design exploration, to establish a different logic for spatial (and maybe political) organization, where there is a productive encounter between natural and urban environments.

4 The man-made forest

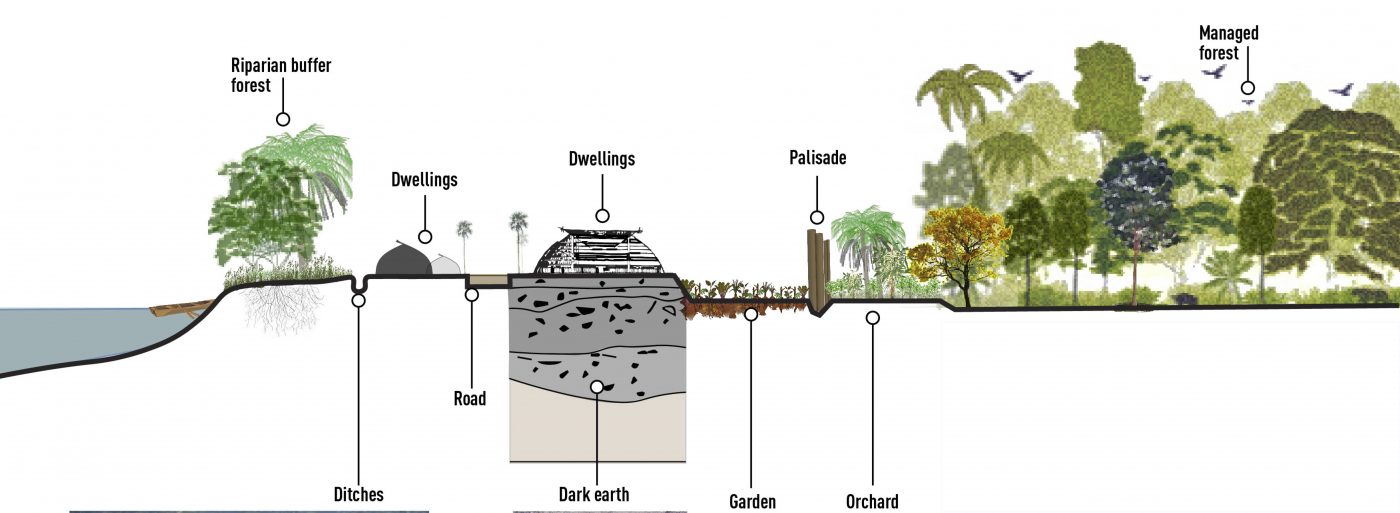

Three thousand years before Europeans arrived in Brazil, Brazilian Indians lived in a web of spread-out civilizations that covered the country’s surface. Opposing the view of “naïf civilizations”, or “pre-civilizations”, several studies show us today that they were organized in quite intricate and elaborate ways. Satellite imagery has revealed the occupation of the Amazonian Upper Xingu area by a system of gardens villages that could be compared to Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities[vii]. These “polities” were responsible for the domestication of the forest: vast areas that we today assume are “pristine natural forests” were really planted and managed landscapes, indicating a high degree of “manufacturing” and yet great balance in the coexistence of man and forest.[viii]

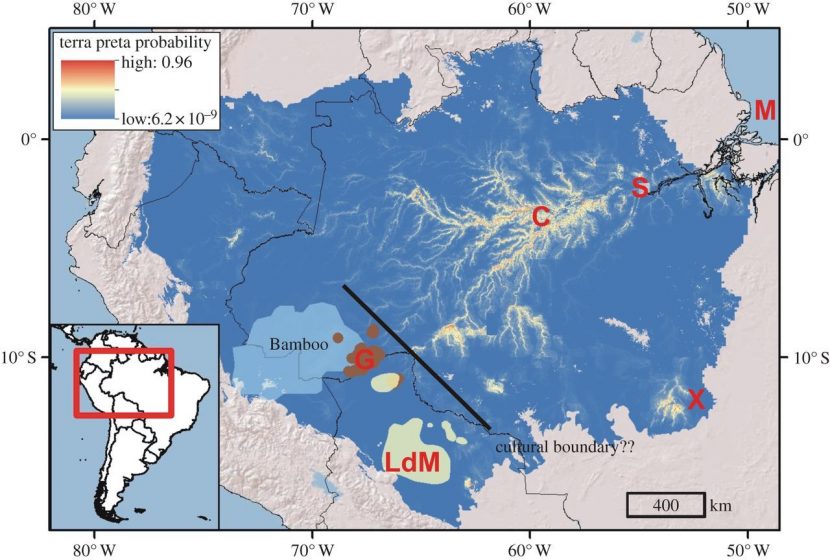

Soil samples from the Amazon Basin tell the story of Pre-Columbian, anthropogenic activity through the analysis of the Amazonian Dark Earths (ADEs). The samples that have been classified as such are rich in macro- and micro-nutrients, in stark contrast to most of the Amazon soil, that is naturally acidic and rich in minerals that are toxic to plants at high concentrations. Layered above the more acid soils, ADEs contain remnants of burnt biomass, are rich in essential minerals like nitrogen, phosphorus, calcium, and zinc and maintain a higher pH that is more forgiving to cultivation. These samples have persisted for centuries because of “fire derived black carbon”, and they have been found in the savannas, rainforests, and various blends of the two across the Amazon Basin. Indigenous cultures have apparently shaped the entire landscape through millennia of coexistence with the environment.[ix]

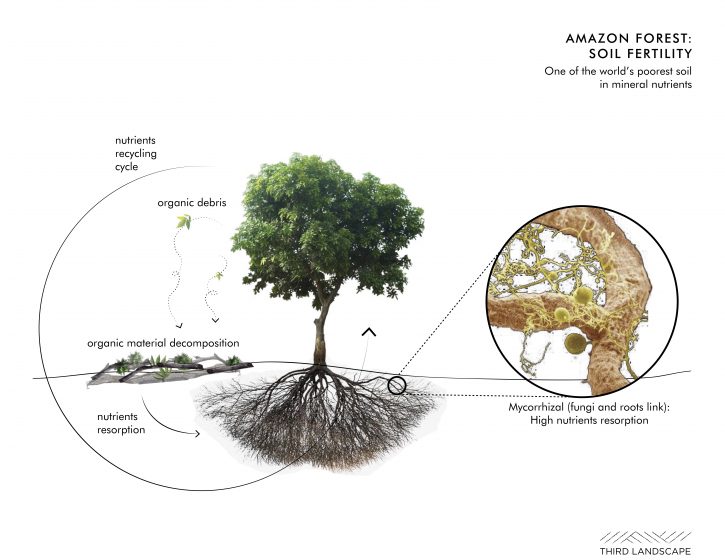

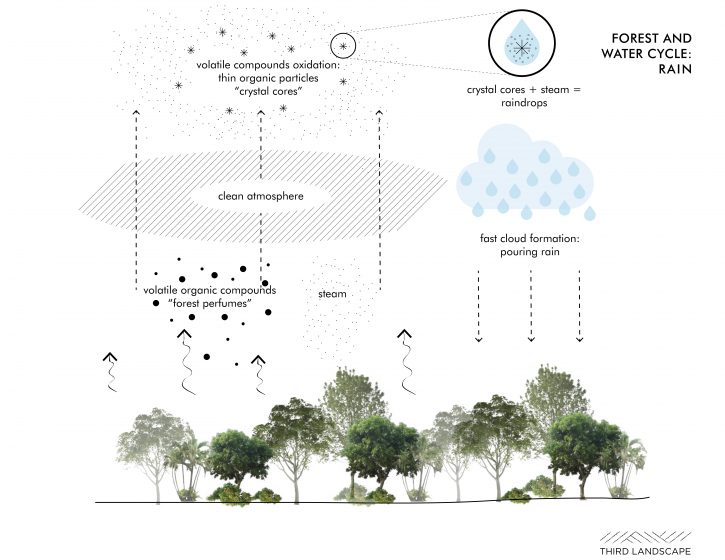

As a rule of thumb, the Amazonian forest stands on a thin layer of nutritious soil, regulated by a fragile balance of natural processes that allow the system to survive interdependently. By ignoring the complexity of its functioning as a sophisticated superimposition of specific elements and conditions, modern agriculture cannot reproduce the fertility of the original soil in the long term, as many collapsed attempts have shown us.

The discourse of pushing the “integration” of the Amazon into the economic logic of the country, and ultimately global capital, will be a failed experiment in the long run. Cities and rural settlements that were implemented in the region since the seventies, along a web of highways and throughways constructed by the military regime, are today the focus of the worst environmental disasters, pushing deforestation and fires to dangerous levels. The political inclination of the current federal government to further advance with this strategy adds a level of urgency to the Amazonian issue that we have not seen since the 60’s, when its indigenous population was considered “extinguished”.

In contrast, “By creating gradients of forests that mutually activated each other – the riparian buffer, the orchard, the managed forest and the gardens –these [indigenous] societies have avoided soil deterioration and could [can]therefore develop complex social relations and durable places of habitation.“[x]

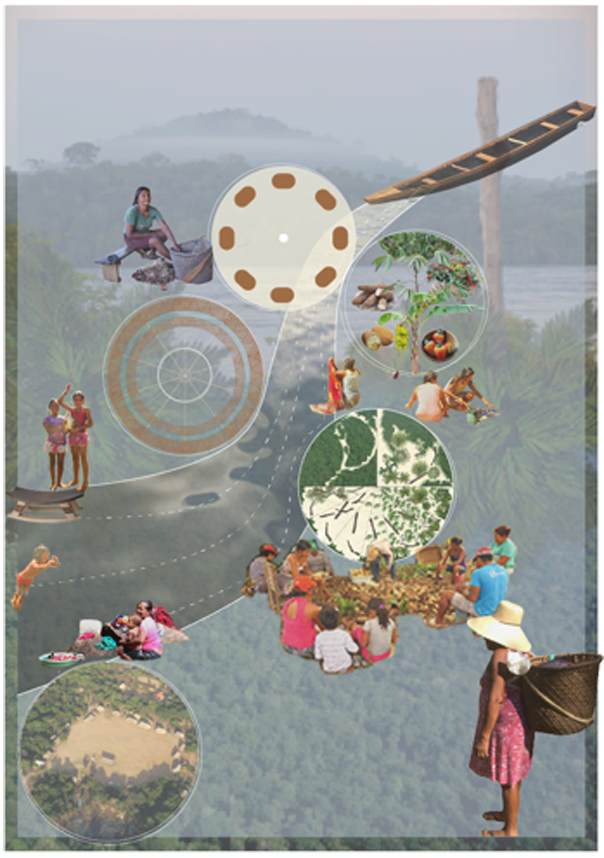

These spatial arrangements are imbedded in a social imaginary that is different than ours and that, in admittedly oversimplified ways, will be here described by the pinpoint of four characteristics: fluidity, kinship, cultural territory and subsistence. [xi] In this imaginary, patterns of flexibility, cohesion between man and nature and a non-hierarchical connection between socio-economic practices, natural cycles, and cultural traits form a cohesive system that I have called Circular Culture:

Fluidity: In Latin American indigenous mythology, nature and humans are bound by a “common spirit”. Our bodies and forms are transitional, pertaining to a world that is “all people”. The Brazilian anthropologist Viveiros de Castro borrowed from German philosophy to coin the term Amerindian Perspectivism[xii] to explain this way of seeing things. As he points out, in this world relations are formed between subjects with different perspectives, be it between humans, or between humans and non-humans. There is no “subdued object” and the separation between nature and human (Foster’s metabolic rift) diminishes.

Co-related notions extend to ideas of fluid time and fluid space, where boundaries are related to natural elements and events, rather than to abstract concepts of time or property. Acknowledging their importance in the structural organization of things, rivers acquire the status of deities, being the most important elements of continuity, both as means of transportation, as well as means of subsistence;

Kinship: Since the Enlightenment, when theories of natural rights[xiii] started to shape modern man as owner of his own, individual rights, we have valued individuality above community, disassociating both as opposing values. In Indigenous social organization, individuals are intertwined with the idealization of the group and its traditions. In some communities the symbiosis between the two is such, that political forces are horizontalized and apparently “non-hierarchical”, relying on an organic understanding of practices.[xiv]

As pointed out by Pierre Clasters in his book Society Against the State, Brazilian Indigenous societies rely on a political structure with no coercion, where the figure of the leader is important and respected but has no freedom to decide for the group. In periods of peace, leaders act as mediators, peacemakers and providers, and are constantly put in check by the group. “Greed and power are incompatible; to be a chief it is necessary to be generous.”[xv]

Cultural Territory: Without prescriptive boundaries (therefore fluid), the indigenous territory is defined by historical occupation, use and the capacity of those who occupy (and define) it to defend its natural resources. Boundaries are porous and with strong interdependence between man and land. In both the symbolic and physical worlds, culture and territory are interrelated in defining each other.

Subsistance: In a social logic that doesn’t aim for accumulation, concepts of modern capitalism are subverted, as individual supremacy, objectification of relationships and commodification of values don’t prevail. The construction and management of inhabited landscapes and “cities” will also obviously differ from ours.

Turning to Indigenous communities to understand the forest and how we should relate to it as we deal with different degrees of urbanization and extraction patterns, will allow us to question the socio-political parameters that are now threatening the natural balance of the whole Amazonian system, as it could guide us to a more holistic approach where natural, cultural, and economic realities intersect as guides, much in tune to what Sir Patrick Geddes practiced more than a hundred years ago, and trends of “regionalism thinking” are currently practicing too.

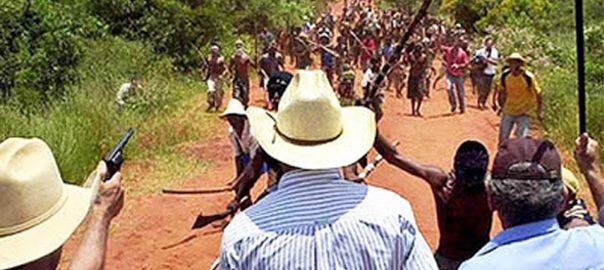

It is relevant to notice that indigenous communities are very much imbedded and active in the Brazilian political life, with strong connections to a global web of institutions and governments. The 1988 Brazilian Constitution guaranteed the preservation of their livelihood and laid the framework for the demarcation of Indigenous Territories, which today occupy 13% of Brazil’s total area, if we only account for those already legally established. Ninety percent of these lands are in the Amazonian biomes and together are a real safeguard for the natural environment. Supporting them in deciding how their territories should be managed and how their “cities” could be shaped, will engender design propositions that could be applied beyond the indigenous territories and into the growing net of small and medium-sized cities that populate the different biomes of the Forest.

Anna Dietzsch

New York and São Paulo

Notes:

Pict 13 – Indigenous community protesting in Brasilia, Brazil. Photo by Valter Campanato, Agencia Brasil

[i] Lefebvre, H. (1970). La révolution urbaine (Vol. 216). Paris: Gallimard.

[ii] Thomas Lovejoy

[iii] Bertha

[iv] Gibson-Graham –Postcapitalist Politics, University of Minnesota Press, 2006

[v] Castells, Manuel – The Rise of the Network Society, Blackwell Publishers, 1996

[vi] Solnit, Rebecca – A Hope in the Dark, Nation Books, 2004

[vii] E. Howard Garden City

[viii] Michael Hekenberger

[ix] Arroyo-Kalin, M., E.G. Neves & W.I. Woods. 2008.

[x] Margit, Andrea – Amazon Inaginaries, Masters’ Thesis for the Harvard Graduate School of Design, 2017

[xi] Andrea Margit

[xii] Viveiros de Castro

[xiii] Thomas Aquina and Locke, etc.

[xiv] Viveiros de Castro – Araweté

[xv] Pierre Clasters

Leave a Reply