Urban gardening can be adapted to the reality of Santiago and other cities with similar characteristics. In Santiago, urban gardens that provide secure sources of healthy food could be implemented not only in common spaces, roofs, and balconies but also in median strips and tree pits along streets.

In Chile, the first infected person was confirmed on 3 March 2020. Since then, the government has decreed several measures including mandatory quarantine, lock-down, border closure, and the closing of urban parks, nature parks, and nature reserves. Despite these restrictions, four months later, there were more than 280,000 cases in Chile.

The government and media have mainly focused on the number of infected persons, whether or not to continue with the quarantines/lock-down, and when to resume normal social and economic activities. But other situations are happening at the same moment that can’t be overlooked.

Due to the crisis, many people have shopped excessively in supermarkets, generating a shortage in the food supply and leading to a surge in pricing. Adding to this, the economic impacts of the pandemic have led to reduced pay and/or loss of employment for many, making it very difficult for them to maintain themselves and their families. For these families, food supply has been a daily challenge since the crisis started. The COVID-19 magnifies the inequalities that have always existed, food security being a basic amenity.

In this context, questioning our source of food supply and distribution is imperative. Is it safe, healthy, and accessible? While advocated quite widely for years, urban gardening presents itself as a highly viable practice to ensure food security in times of crisis like the one we are experiencing (Armanda et al. 2019; Poulsen et al. 2015). Urban gardening refers to the production of vegetables within the urban context (Wunder, 2013), being one of the most common activities of urban agriculture. The scale of vegetable production can be highly variable, from community and collective gardens to a micro-scale production such as roof-top gardens, green walls, backyards gardening, and street landscaping (Pearson et al. 2010; Dinis et al. 2018).

Urban gardening in Santiago, Chile, is an activity that is in an early stage. It is mainly developed by civil organizations such as NGOs, artists, neighborhood organizations, and university initiatives, although it is also supported by some municipalities (Contesse et al. 2018). In general, the development of urban gardening has been associated mainly with community gardens. However, there are no available studies on the development of urban gardening on the micro-scale even though it has become more popular in recent years.

Considering the COVID-19 crisis, where thousands of people have been under lock-down with reduced social interactions, the development of urban gardening on a micro scale is emerging as the most appropriate alternative.

While the virus does not distinguish between sex, age, or origin, those living in small spaces, in overcrowded conditions and without sufficient economic resources to support themselves are undoubtedly more vulnerable. In Santiago, there have been several demonstrations during the course of the pandemic. For these communities, food insecurity is a matter of survival.

Vulnerable communities are often located in high-density urban and peri-urban areas. In low-housing neighborhoods, houses are in precarious conditions, gardens are usually expanded to incorporate more family members, generating overcrowded conditions. Similar conditions are seen in high housing neighborhoods. In both cases, there are few green areas or quality public spaces available, and they are commonly associated with insecurity and crime. Slums are extreme examples where vulnerable families live in more than precarious conditions.

When we think about the incorporation of urban gardening not only in the context of low income but also of high-density neighborhoods where the availability of public and private space is limited, it becomes necessary to look for alternatives that can adapt to these specific conditions. Sack gardening is an urban gardening method that is suitable to be implemented in such conditions. In this method, vegetables are planted on the top and sides of sacks. Gallaher et al. (2013) found that sack gardening in the Kibera slums of Nairobi, Kenya, has a great impact on families’ food security. Faced with challenges of severe poverty and malnutrition, sack gardening in Nairobi has made an important contribution to increasing the diversity of the households’ diet and being a source of nutrition in times of shortage (Gallaher et al., 2013). The use of sacks allows people to produce several vegetables in a limited space that they usually share within their communities.Another example of urban gardening in similar contexts is the roof-top and balcony gardening in Rio de Janeiro’s “favelas”. Since 2003, the Brazilian government has provided funding for urban agriculture projects, one of which is the urban gardening project in the favelas, part of Rio’s Sustainable City program (Ortiz, 2012). People interested in growing vegetables participate in an organic agriculture workshop that educates them on different techniques for growing crops in household planters. People usually share their terraces or balconies to garden with neighbors, that is to say: plant, maintain and harvest together lettuce, arugula, watercress, cherry tomatoes, rosemary, and mint, among other vegetables and herbs (Ortiz, 2012). The possibility of planting in underused spaces such as roof-tops and balconies allow people to develop urban gardening despite living in high urban density contexts.

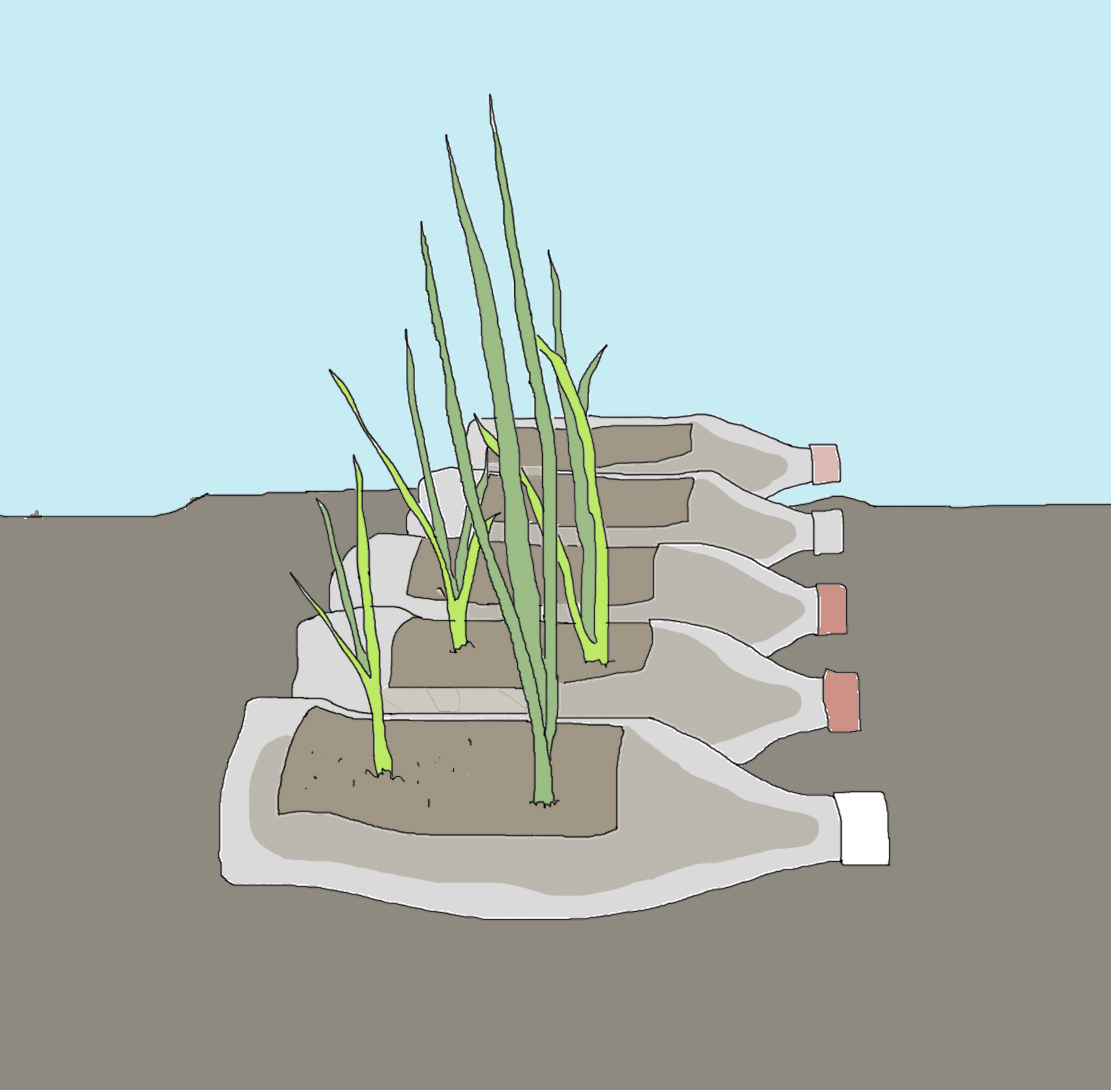

Both examples of urban gardening can be adapted to the reality of Santiago and other cities with similar characteristics. In Santiago, urban gardens could be implemented not only in common spaces, roofs, and balconies but also in median strips and tree pits along streets. As crop containers, sacks are easily available materials and can have great acceptance to be used as containers. In addition, there are many other materials that are usually discarded and can be reused for cultivation: bottles, tires, and pallets.

All these different procedures of urban gardening can be developed by the families themselves at a very local scale with the potential to expand to the community scale. In these times of reduced social contact, urban gardening projects could augment community building in innovative ways and build upon the social potential of these communities. The possibilities to exchange different types of vegetables and to sell them in order to have an extra income are activities that can still be done within the restrictions advised during the pandemic. Working in shifts to avoid person-to-person contact can be an alternative to maintain the crops, without losing the support within the community members. Urban gardening at the community level could nurture these relationships and help communities as a cohesive unit to overcome the current crisis and be better prepared for future events.

Urban gardening can be a response to a safer, healthier, and accessible way of food supply and distribution. It is more secure, especially as it can help families from being affected by shortages of supply, ensuring at least basic nutrition. It is healthier, not only because of the contribution of organic vegetables to the diet, but also due to local availability either at home or within the community reducing the need to travel too far to shop, and thus reducing the risk of contagion. This would also reduce food being passed through several “hands” before reaching the consumer. And accessible, because of the availability and low resources required for production and distribution.

Families do not have to be in dire need of producing their own food, but when the state is unable to guarantee the food security of its citizens, alternatives such as this should be supported, especially because the role of the state is fundamental, even more in times of crisis. Santiago de Chile has a path initiated in urban gardening that has great potential for further development, and this may be an opportunity for that. Education on urban gardening would allow local residents to engage in it. The circulation of manuals and development of workshops suggesting the types of vegetables and how, where and when to plant them, along with the delivery of basic materials such as soil and seeds, would be a first step to offer communities tools to better cope with this crisis and empower them in urban gardening development. NGOs, the local government, or even universities, can be key stakeholders in developing this educational process.

The COVID-19 crisis not only raises the question of how vulnerable we are as people, but also whether the way we are building ourselves as a society benefits us all or not. The traditional form of food supply has been stretched to its limit, and it is important that we implement other alternatives as soon as possible.

Constanza M. Cerda

Stuttgart

References:

Armanda D., Guineé J. and Tukker A., 2019. ‘The second green revolution: Innovative urban agriculture’s contribution to food security and sustainability – A review’. Global Food Security 22 (2019) 13–24. Elsevier.

Contesse M., van Veliet B. and Lenhart J. 2018. ‘Is urban agriculture urban green space? A comparison of policy arrangements for urban green space and urban agriculture in Santiago de Chile’. Land use policy 71 (2018) 566-577. Elsevier.

Dinis, A., Marquez R., Santos C. and Martins, M. (2018) ´ Urban Agriculture: A tool for towards more resilient urban communities?´ Environmental Science & Health 2018 5:93-97, Elsevier.

Gallaher C., Kerr J., Njenga M., Karanja N. and WinklerPrins A., 2013. ‘Urban agriculture, social capital, and food security in the Kibera slums of Nairobi, Kenya’. Agric Hum Values (2013) 30:389–404.

Ortiz F. 2012. Urban Agriculture Sprouts in Brazil’s Favelas. Tierramerica. September 25, 2012.

Pearson C., Pilgrims S. and Pretty J., 2010. ‘Urban agriculture: diverse activities and benefits for city society’. Ed. Earthcan 2010.

Poulsen M., McNab P., Clayton M. and Neff R., 2015 ‘A systematic review of urban agriculture and food security impacts in low-income countries’. Food Policy 55, 131-146.

Taylor, W., and Goodfellow T. 2009. ‘Urban poverty and vulnerability in Kenya: The urgent need for coordinated action to reduce urban poverty’. Nairobi: Oxfam GB Kenya Programm.

Wunder S. (2013) Learning for sustainable agriculture: Urban gardening in Berlin. With particular focus on Allmende Kontor. Support of Learning and Innovation Networks for Sustainable Agriculture SOLINSA.

La horticultura urbana como respuesta a los problemas de suministro de alimentos en zonas urbanas densas durante la crisis de COVID-19

Los huertos urbanos pueden adaptarse tanto a la realidad de Santiago como a otras ciudades de características similares. En Santiago, los huertos urbanos, que proporcionan una fuente segura de alimentos saludables, podrían implementarse no sólo en espacios comunes, techos y balcones, sino también en los bandejones centrales y en las bases de infiltración para árboles a lo largo de las calles.

En diciembre de 2019, en la ciudad de Wuhan, China, se reportó el primer caso de Corona-virus. Desde ese momento, el virus se ha esparcido rápidamente, llegando a más de 31,300,000 casos a nivel mundial (a septiembre de 2020, según la Universidad de John Hopkins). Tanto global como regionalmente, se han tomado una serie de medidas para desacelerar la propagación del virus, afectando a millones de personas en la forma en la que viven, trabajan, socializan y se abastecen.

En Chile, el primer contagio fue confirmado el 3 de marzo del 2020. A partir de ese día, el gobierno chileno decretó medidas como: cuarentena obligatoria, bloqueo de las fronteras y cierre de parques urbanos y reservas naturales. Pese a estas restricciones, cuatro meses después, el número de contagios alcanzaba la suma de 280,000 casos.

Tanto el gobierno como los medios de comunicación han puesto su foco de atención en el número de personas infectadas, si continuar o no con las cuarentenas y bloqueos, y cuándo comenzar a retomar las actividades sociales y económicas. Sin embargo, hay otros eventos, ocurriendo a la par de la crisis, que no deben ser pasados por alto.

Debido a la crisis, muchas personas se han sobre abastecido, generando escasez en el suministro de alimentos y con ello alza en sus precios. Sumado a esto, las repercusiones económicas de la pandemia han llevado a una reducción generalizada de los salarios y/o a la pérdida de empleos, haciendo aún más difícil que las familias puedan abastecerse. Para estas familias, el suministro de alimentos ha sido un desafío diario desde el inicio de la crisis. Sin dudas, la crisis generada por el COVID-19, ha magnificado las desigualdades sociales que siempre han existido, siendo la seguridad alimentaria una necesidad básica que ha quedado expuesta como un ámbito especialmente frágil.

En este contexto, cuestionarse sobre las fuentes de abastecimiento y distribución de alimentos es imperativo: ¿Son ellas seguras, saludables y accesibles? Aunque se han defendido ampliamente durante años, los huertos urbanos se presentan hoy como una práctica especialmente viable para garantizar la seguridad alimentaria en tiempos de crisis como la que estamos viviendo (Armanda et al. 2019; Poulsen et al. 2015). Los huertos urbanos conllevan la producción de hortalizas dentro del área urbana (Wunder, 2013), siendo ellos una de las actividades más comunes de la agricultura urbana. La escala de producción de hortalizas puede ser muy variable, desde huertos comunitarios y colectivos hasta una producción a micro-escala, como los huertos de techo, los muros verdes, los huertos en patios y en las áreas verdes de acceso público (Pearson et al. 2010; Dinis et al. 2018).

En Santiago de Chile, el desarrollo de huertos urbanos se encuentra en una etapa temprana. Principalmente, ha sido impulsado por organizaciones civiles, tales como ONGs, artistas, organizaciones vecinales e iniciativas universitarias y, en algunos casos, han sido apoyados por municipios (Contesse et al. 2018). En general, el desarrollo de los huertos urbanos se ha llevado a cabo a través de huertos comunitarios, y a pesar de que su desarrollo en la micro-escala se ha hecho más popular en los últimos años, aún no se dispone de estudios sobre ello.

Si considerarnos que durante la crisis del COVID-19, miles de personas han debido permanecer en sus hogares y reducir al mínimo sus interacciones sociales, el desarrollo de los huertos urbanos en la micro-escala, se perfila como la alternativa de abastecimiento de alimentos más adecuada.

Si bien el virus no distingue entre sexo, edad u origen, quienes viven en espacios reducidos, en condiciones de hacinamiento y sin recursos económicos suficientes para mantenerse, se constituyen, indudablemente, como el grupo más vulnerable. En Santiago, se han llevado a cabo una serie de protestas ciudadanas durante el transcurso de la pandemia, dejando al descubierto que para estas comunidades, la inseguridad alimentaria es una cuestión de supervivencia.

Las comunidades vulnerables suelen localizarse en zonas urbanas y periurbanas de alta densidad. En los barrios de baja altura, las viviendas se encuentran generalmente en condiciones precarias, los patios suelen modificarse para incorporar a más miembros de la familia, generando condiciones de hacinamiento. En los barrios de viviendas en altura, se observan condiciones similares. En ambos casos, el acceso a áreas verdes o espacios públicos de calidad es limitado, siendo lugares que se identifican comúnmente como espacios inseguros. Los campamentos son un ejemplo de la extrema precariedad en los que viven cientos de familias vulnerables.

Cuando pensamos en la incorporación de los huertos urbanos en contextos no tan sólo de bajos ingresos, sino también de alta densidad urbana, donde la disponibilidad de espacio público y privado es limitada, se hace necesario buscar alternativas que puedan adaptarse a estas condiciones específicas. El cultivo en sacos, es una forma de huerto urbano adecuada para ser implementada en tales condiciones. En este método, las hortalizas son plantadas tanto en la parte superior como en los costados de los sacos. Gallaher et al. (2013) descubrieron que el cultivo en sacos realizado en los barrios marginales de Kibera, en Nairobi (Kenya) tiene un gran impacto en la seguridad alimentaria de las familias. Frente a los desafíos de la extrema pobreza y la malnutrición, la horticultura en sacos de Nairobi ha contribuido de manera importante a aumentar la diversidad de la dieta de las familias, además de constituirse como una importante fuente de nutrición en épocas de escasez (Gallaher et al., 2013). El uso de los sacos ha facilitado la producción de verduras en un espacio limitado, que usualmente comparten con el resto de la comunidad.

Otro ejemplo de huertos urbanos en contextos similares son los huertos en techos y balcones de las “favelas” de Río de Janeiro. Desde el año 2003, el Gobierno del Brasil ha proporcionado financiación para proyectos de agricultura urbana, uno de ellos, es el proyecto de huertos urbanos en las favelas, que forma parte del programa de Ciudad Sostenible de Río (Ortiz, 2012). Las personas interesadas en cultivar hortalizas participan en talleres de agricultura orgánica, en donde se les enseña diferentes técnicas de cultivo en sembradoras domésticas. La gente suele compartir sus terrazas o balcones para cultivar con sus vecinos, esto implica: plantar, mantener y cosechar en conjunto lechugas, rúculas, berros, tomates cherry, romero y menta, entre otras verduras y hierbas (Ortiz, 2012). La posibilidad de plantar en espacios infrautilizados -como tejados y balcones- permite a las personas desarrollar huertos en contextos de alta densidad urbana.

Ambos ejemplos de huertos urbanos pueden adaptarse a la realidad de Santiago de Chile y de otras ciudades de características similares. En Santiago, los huertos urbanos podrían implementarse no sólo en espacios comunes, techos y balcones, sino también en bandejones centrales y en las bases de infiltración para árboles a lo largo de las calles. Los sacos son materiales de fácil acceso que pueden tener una gran aceptación para ser utilizados como contenedores, además de otros materiales que suelen desecharse y pueden reutilizarse para el cultivo, tales como botellas, neumáticos y pallets.

Todas estas modalidades de huertos urbanos pueden ser desarrolladas por las propias familias, a escala local y con el potencial para expandirse a escala comunitaria. En tiempos de contacto social restringido, los proyectos de huertos urbanos podrían potenciar las relaciones comunitarias de forma innovadora, aprovechando el potencial social de las comunidades. Las posibilidades de intercambiar diferentes tipos de hortalizas y venderlas para tener un ingreso extra, son actividades que pueden realizarse dentro de las restricciones aconsejadas durante la pandemia. El trabajo por turnos para evitar el contacto de persona a persona, por ejemplo, puede ser una alternativa para mantener los cultivos, sin perder la participación de los miembros de la comunidad. Los huertos urbanos podrían fomentar las relaciones a nivel comunitario, contribuyendo a las familias a superar la actual crisis y con ello, a estar mejor preparadas para eventos futuros.

Los huertos urbanos pueden ser la respuesta para una forma más segura, saludable y accesible de abastecimiento y distribución de alimentos. Es una forma más segura, al permitir que las familias no se vean tan afectadas por la escasez de suministro, asegurando al menos una nutrición básica. Es más saludable, no sólo por la contribución de hortalizas orgánicas a la dieta, sino también por su disponibilidad: un cultivo en el hogar o en la comunidad reducirá la necesidad de viajar para ir de compras y contribuirá a la disminución del riesgo de contagio (este factor también reduciría el riesgo de que los alimentos pasen por varias “manos” antes de llegar al consumidor). Y accesibles, dado los bajos recursos necesarios para su producción y distribución.

Si bien las familias no tienen por qué tener la necesidad imperiosa de producir sus propios alimentos, cuando el Estado es incapaz de garantizar la seguridad alimentaria de sus ciudadanos, existen medidas alternativas como los huertos urbanos, apropiados para tiempos de crisis como la que estamos viviendo. Santiago de Chile tiene un camino iniciado en los huertos urbanos, con un gran potencial de desarrollo, siendo ésta una oportunidad para ello. La educación en materia de huertos urbanos permitiría a los residentes locales participar en la producción local. La distribución de manuales y la realización de talleres en los que se sugieran los tipos de hortalizas adecuadas para cultivar y eduquen sobre cómo, dónde y cuándo plantarlas, junto con la entrega de materiales básicos como tierra y semillas, sería un primer paso para ofrecer a las comunidades más herramientas para afrontar mejor esta crisis y para potenciar el desarrollo de los huertos urbanos. Las ONGs, el gobierno local o incluso las universidades podrían conformarse como los principales actores interesados en el desarrollo de este proceso educativo.

La crisis de COVID-19 no sólo plantea la cuestión de cuán vulnerables somos como personas, sino también si la forma en que nos estamos construyendo como sociedad nos beneficia -o no- a todos. La forma tradicional de suministro de alimentos se ha forzado hasta su límite, y es importante que pongamos en práctica otras alternativas lo antes posible.

Constanza M. Cerda

Stuttgart

References:

Armanda D., Guineé J. and Tukker A., 2019. ‘The second green revolution: Innovative urban agriculture’s contribution to food security and sustainability – A review’. Global Food Security 22 (2019) 13–24. Elsevier.

Contesse M., van Veliet B. and Lenhart J. 2018. ‘Is urban agriculture urban green space? A comparison of policy arrangements for urban green space and urban agriculture in Santiago de Chile’. Land use policy 71 (2018) 566-577. Elsevier.

Dinis, A., Marquez R., Santos C. and Martins, M. (2018) ´ Urban Agriculture: A tool for towards more resilient urban communities?´ Environmental Science & Health 2018 5:93-97, Elsevier.

Gallaher C., Kerr J., Njenga M., Karanja N. and WinklerPrins A., 2013. ‘Urban agriculture, social capital, and food security in the Kibera slums of Nairobi, Kenya’. Agric Hum Values (2013) 30:389–404.

Ortiz F. 2012. Urban Agriculture Sprouts in Brazil’s Favelas. Tierramerica. September 25, 2012.

Pearson C., Pilgrims S. and Pretty J., 2010. ‘Urban agriculture: diverse activities and benefits for city society’. Ed. Earthcan 2010.

Poulsen M., McNab P., Clayton M. and Neff R., 2015 ‘A systematic review of urban agriculture and food security impacts in low-income countries’. Food Policy 55, 131-146.

Taylor, W., and Goodfellow T. 2009. ‘Urban poverty and vulnerability in Kenya: The urgent need for coordinated action to reduce urban poverty’. Nairobi: Oxfam GB Kenya Programm.

Wunder S. (2013) Learning for sustainable agriculture: Urban gardening in Berlin. With particular focus on Allmende Kontor. Support of Learning and Innovation Networks for Sustainable Agriculture SOLINSA.

Leave a Reply