When space is the limitation, the challenge is not to create new green spaces, but rather to focus on improving their quality, including their characteristics, use, and functions.

Green spaces are key elements in curbing the effects produced by urbanization. They have traditionally been considered the city lungs; in addition, they provide multiple benefits, both for people`s health and the well-being of the urban environment sustaining social interaction among residents and their connection with Nature. In many cities, when space is the limitation, the challenge is not to create new green spaces, but rather to focus on improving their quality including their characteristics, use, and functions.

It is common for designers to say that the quality of a public space is measured by the acceptance of the visiting people. But the design of a successful green space depends also on considering the ecosystem services it will offer such as flood mitigation, air pollution reduction, and climate change adaptation. The quality of public green spaces is given by their structural and functional characteristics in relation to the environmental component (infiltration area, tree and herbaceous cover, thermal regulation, noise damping, etc.) and, on the other hand, to the maintained infrastructure and facilities like paths, benches, and playgrounds. That is to say, a good design will depend, not only on for whom the green space has been planned, but also on environmental conditions, especially its climate. What works best for a particular locality will depend on local circumstances; the choice of planting, materials, furniture, fences, pathways, and paving, these must be carefully planned and adjusted to the conditions of the place.

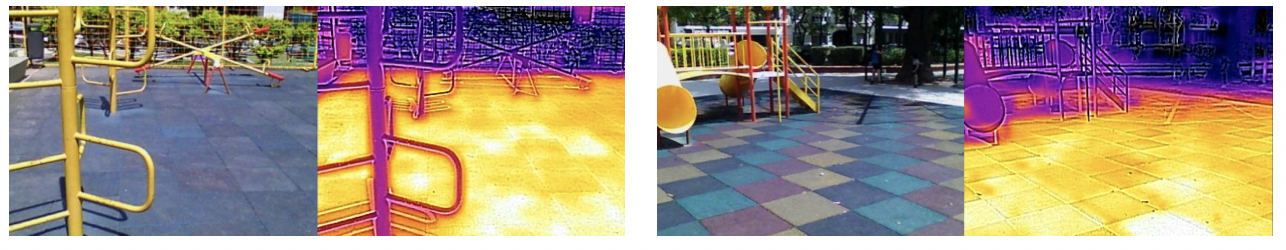

Usually, the specialized bibliography indicates that green spaces provide thermal regulation, being considered places of urban comfort. But what are the consequences of incorporating an incorrect infrastructure? Many of the squares and parks in the city of Buenos Aires can be used to show how a poor choice of infrastructure reverts to discomfort limiting the use of certain facilities at times of greatest sunlight (Fig. 1).

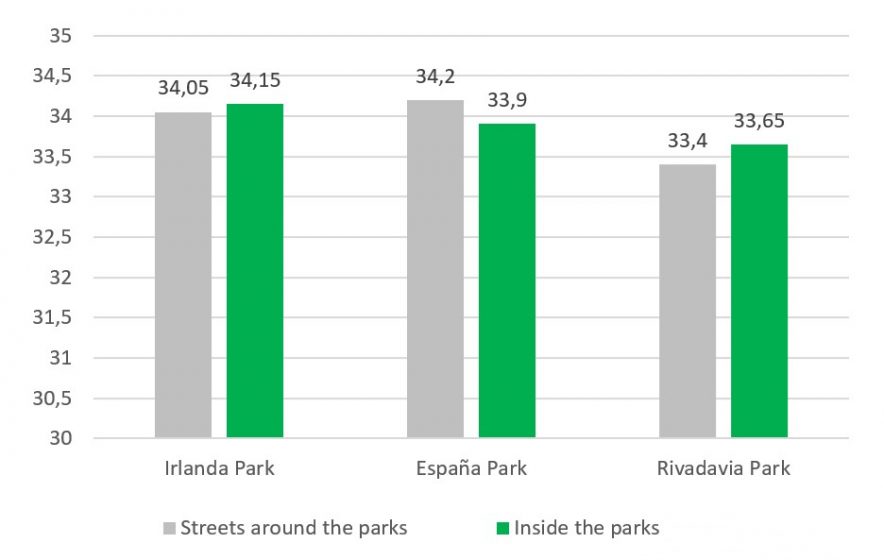

Last year we performed measurements in 14 parks and squares, measuring air and surface temperatures of the different materials used in the park’s construction. To our surprise, we did not find significant differences in air temperature measured inside the park and in the surrounding streets both winter and summer (Fig.2).

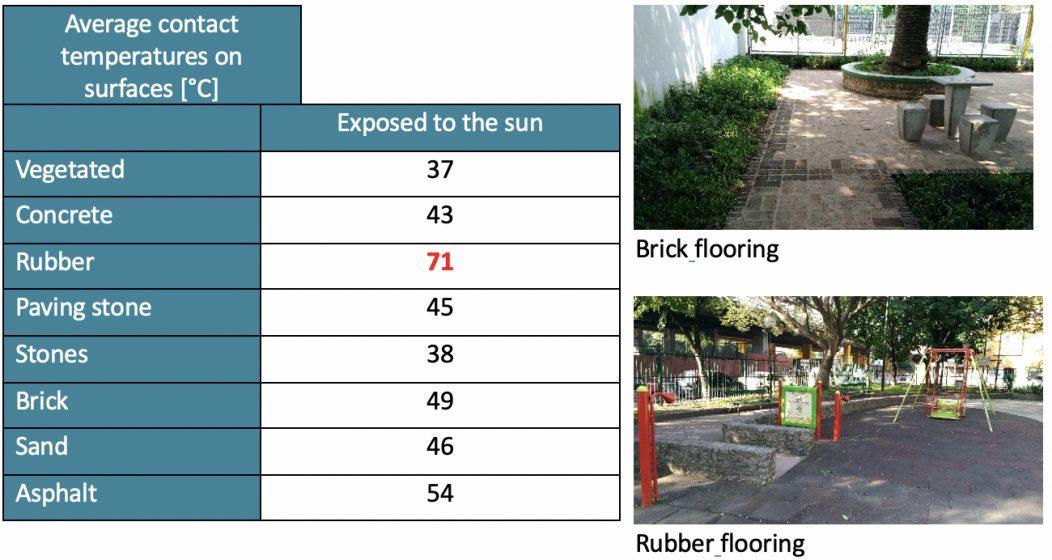

The explanation of finding similar temperatures inside and outside the parks was due to the presence of profuse paved areas that under the sun get much hotter than grass or soil. In addition, the use of scrap tires as a playground cover material is used in several recreational surfaces, including children’s playground areas. On these surfaces, the temperature on a summer day reached 71 degrees Celsius (159.8 F), while on the lawn the contact temperature was only 37 degrees Celsius (98.6 F) (Fig. 3).

Squares (1ha) and medium-sized parks (4 ha) fail to significantly mitigate the urban heat conditions since their own built infrastructure ends up dissipating the cooling effect produced by the green canopy.

It is worrying that the temperature on the floors of the playgrounds reaches, in summer, very high temperatures at midday, which makes this unusable right in the holiday months when families have more time to enjoy outdoors. What’s more, there is evidence of high content of toxic chemicals in these recycled materials used as pavers that can volatilize at higher summer temperatures representing a potential source of carcinogenic dibenzopyrenes to the environment (Llompart et al. 2013). Other chemicals of concern in tires include lead oxide styrene and carbon black nanoparticles.

Consequently, the use of recycled rubber tires should be avoided both for reducing thermal comfort and for its toxicological danger to a greater number of citizens. (Vallette, 2013) and the Healthy Building Network do not recommend the use of tire-derived flooring, especially where small children may come into direct contact with the flooring, as they are at a higher risk of exposure because of normal hand-to-mouth activity (Fig.5). Let’s not forget the reason why the materials suffered wear, it’s that there are loose pieces that can come into contact with children who play in those areas.

The city of Buenos Aires has been carrying out for several years a strategy of improving green spaces to encourage physical activity incorporating infrastructures for active and passive recreation. However, contradictions arise when the consequences of using inappropriate materials are not analyzed in detail. Therefore, it would be necessary to reformulate some projects, evaluating and monitoring the materials they use in the different infrastructures guaranteeing access to green spaces of good quality.

Perhaps we should return to traditional designs where children’s games are located in areas under the trees and, for the floor, only sand, grass, or soil is used (Fig. 6 and 7).

Ana Faggi and Jose Luis Hryckovian

Buenos Aires

References

Llompart, M., Sánchez-Prado, L., Lamas, J.P., García-Jares, C., Roca, E., & Dagnac, T. (2013). Hazardous organic chemicals in rubber recycled tire playgrounds and pavers. Chemosphere, 90 2, 423-31

Vallette J (2013) Avoiding Contaminants in Tire-Derived Flooring, A Healthy Building Network Report | April 2013

about the writer

Jose Luis Hryckovian

Jose Luis Hryckovian is an Environmental Engineer working with me at The Engineer Faculty, Flores University in Buenos Aires.

Leave a Reply