The environmental justice movement has only just begun to systematically frame the disproportionate impacts of climate change as a justice issue. The present absence of strategies and goals for justice in climate adaptation planning is highly problematic.

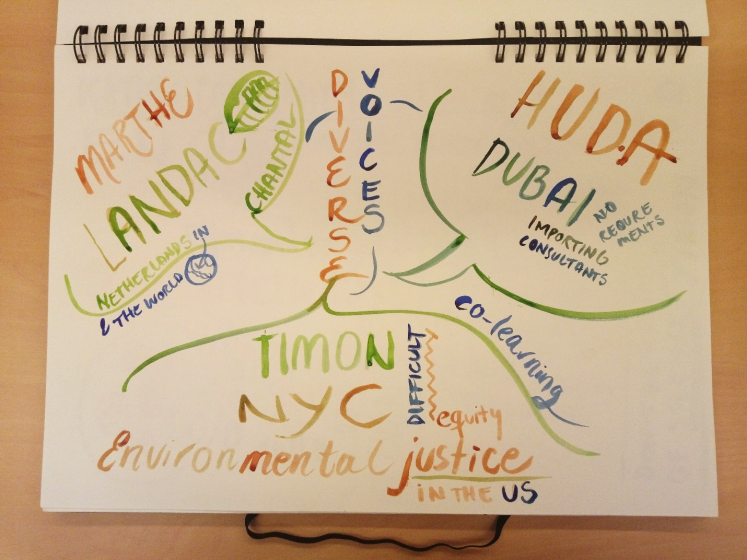

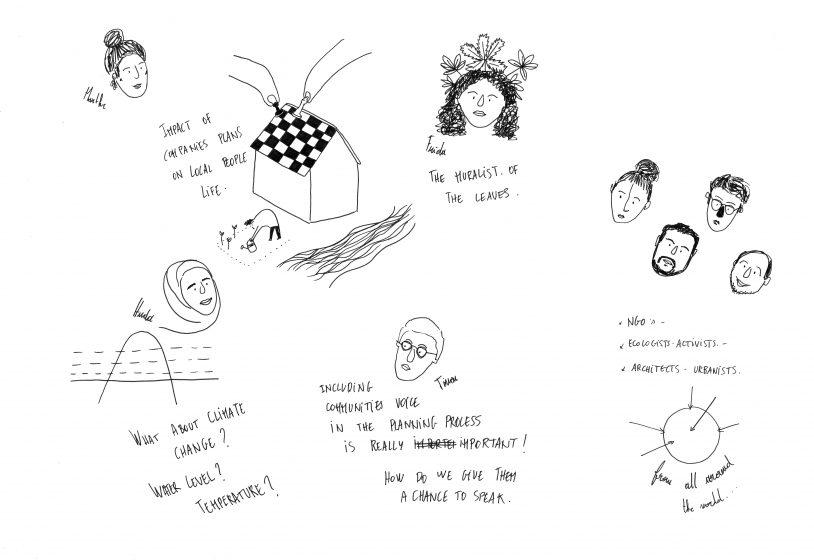

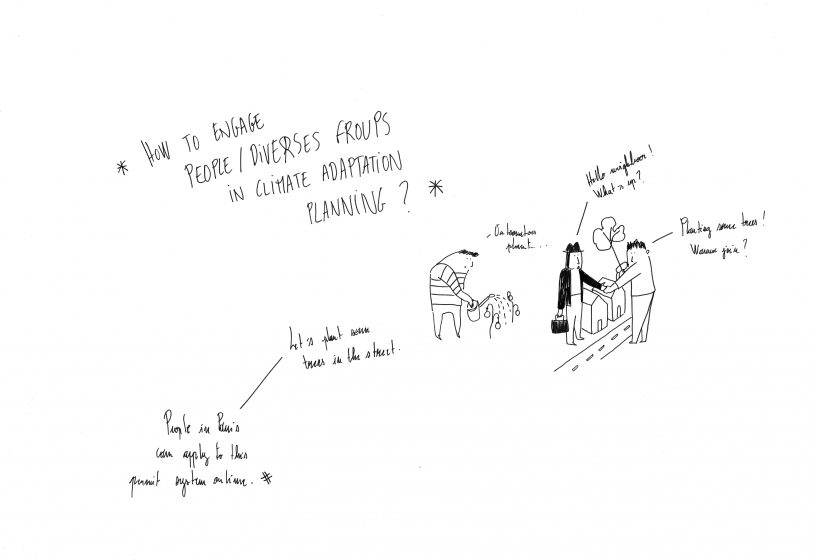

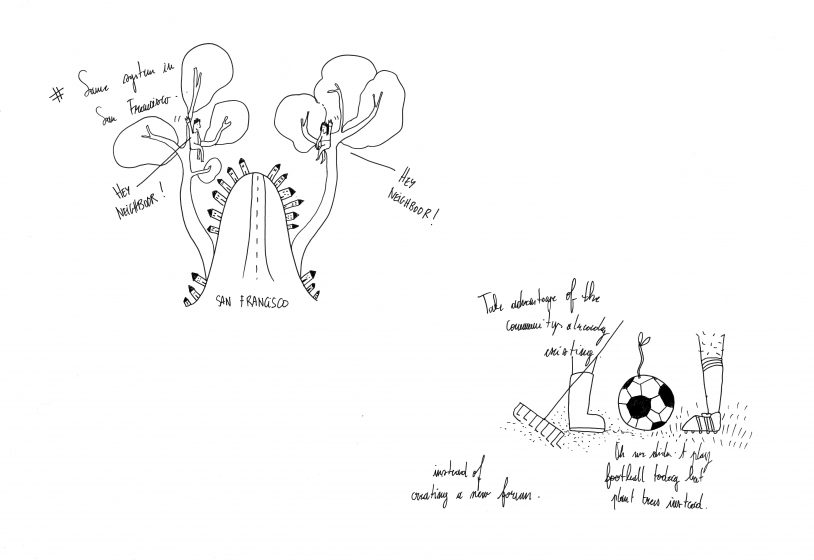

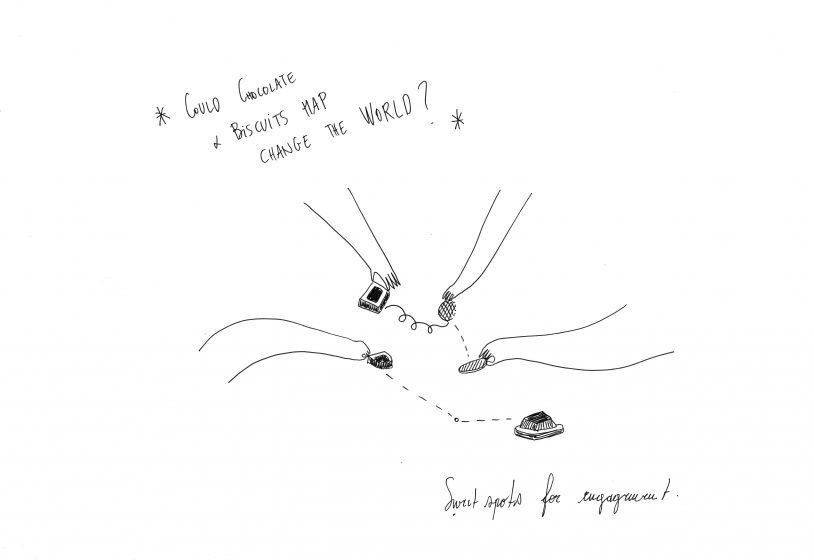

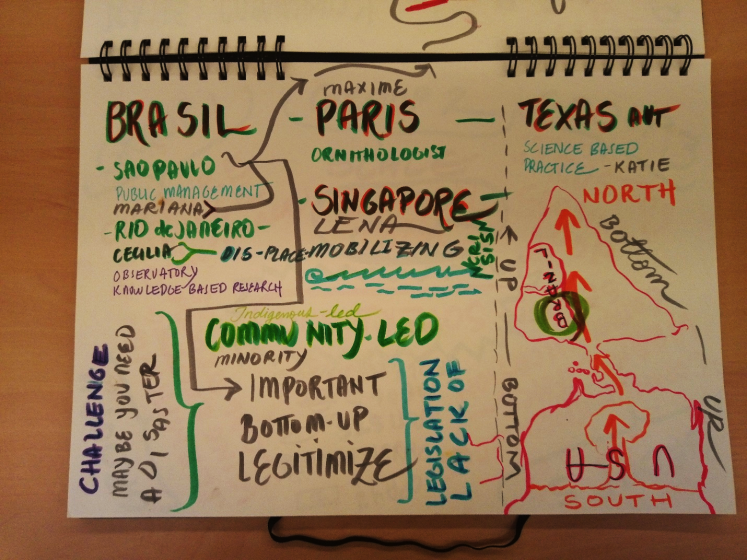

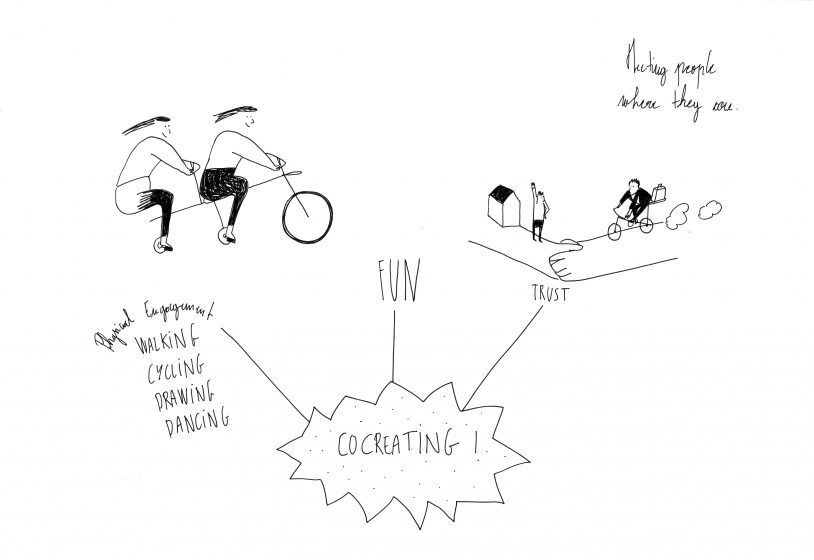

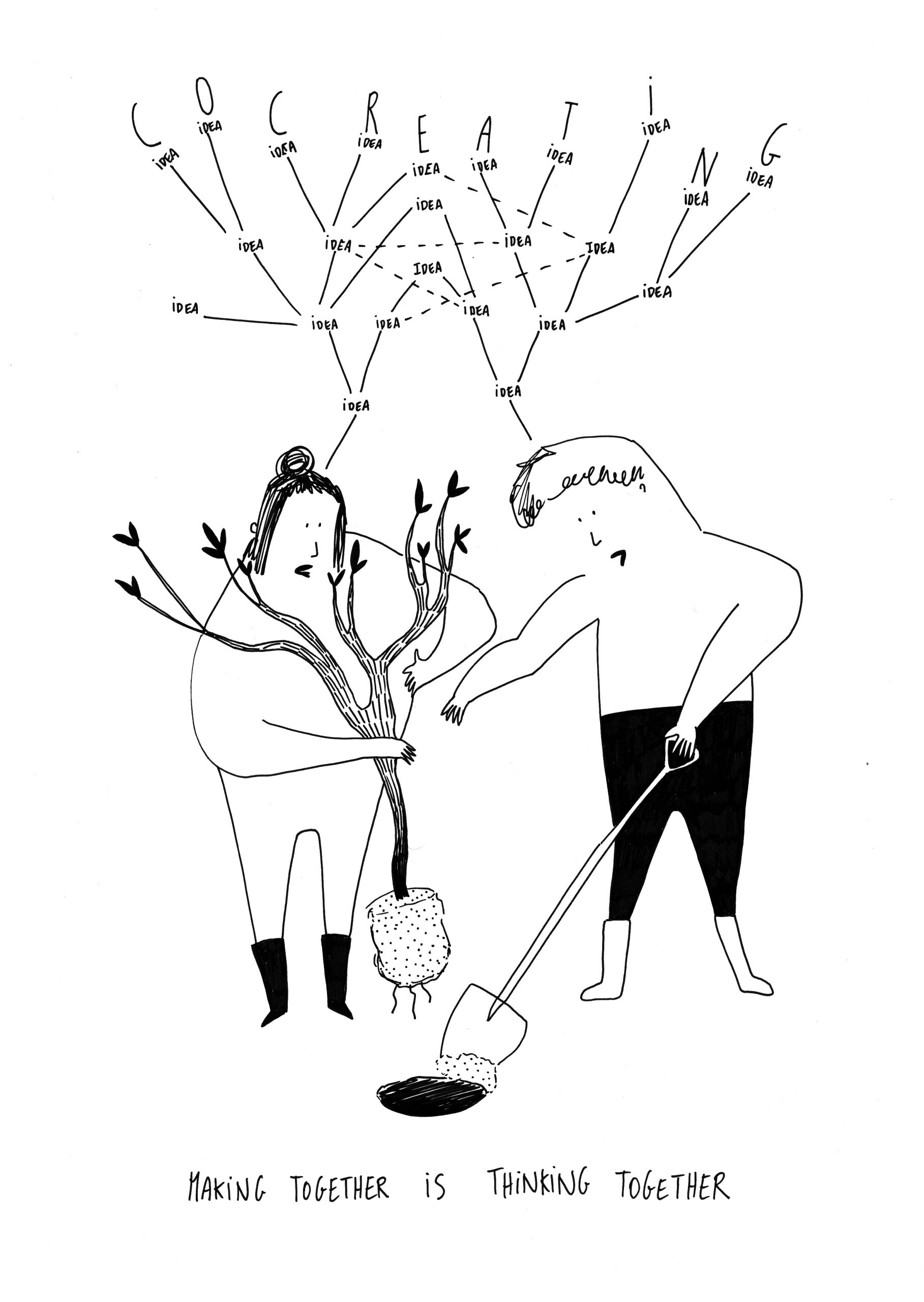

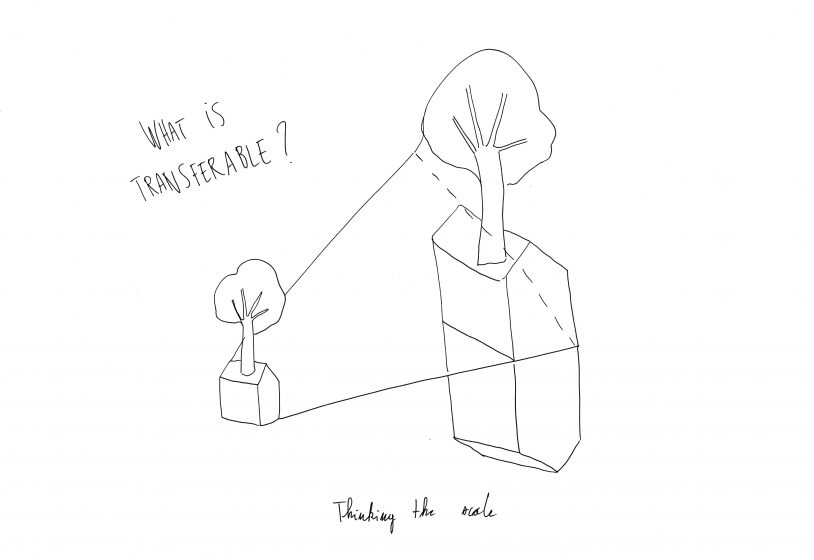

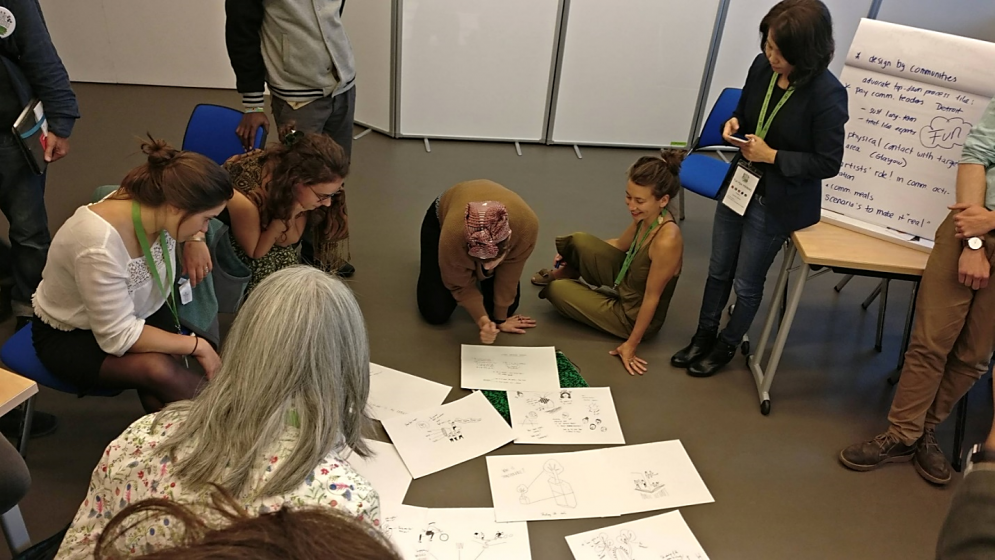

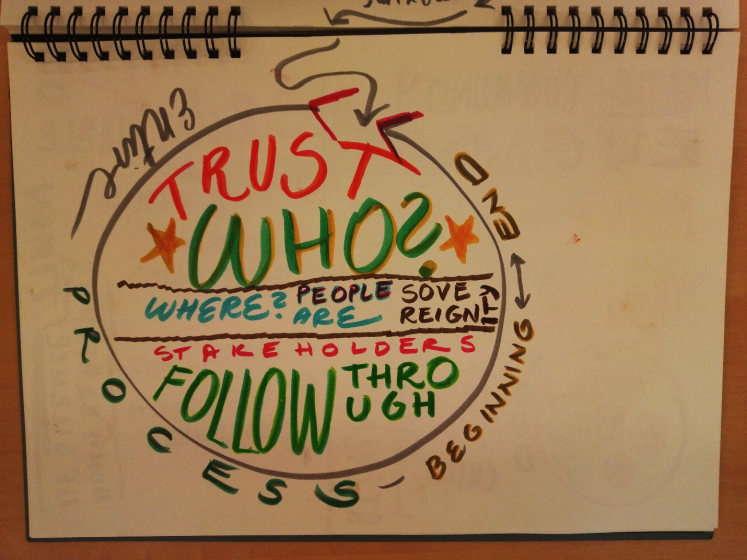

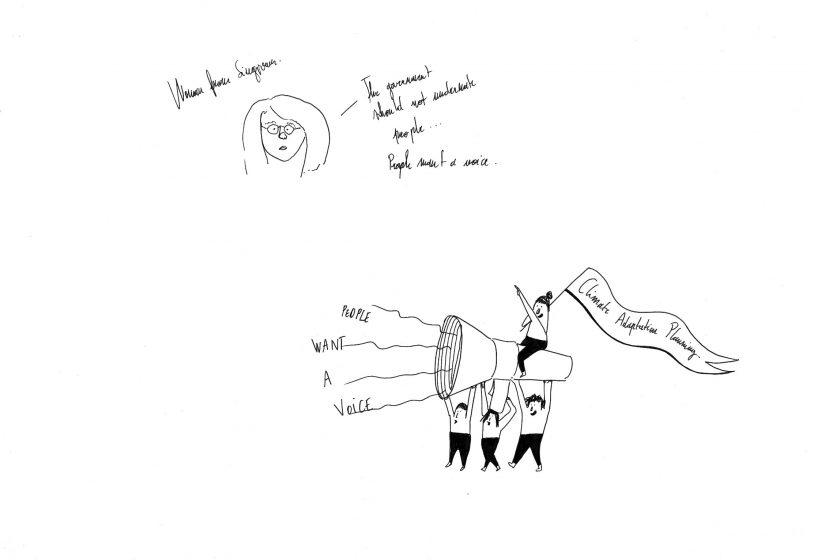

This contribution is the result of a thought-collecting Seed Session during the TNOC Summit in Paris, held on June 5, 2019. Pitches, group breakouts, and a facilitated discussion addressed the question: Including diverse voices in adaptation planning, how do we make it happen? Two illustrators, Frida Larios and Marion Lacourt, enriched the session by creating on the spot artwork to capture the process and ignite creative thinking. These artworks were live outcomes of the session and are integrated into this piece. With our session and this piece, we hope to provide an example of how art and science can enhance each other.

~ ~ ~ We express our heartfelt thanks to all session participants in Paris ~ ~ ~

Climate justice

The primary challenge is this: low-income residents and other marginalized groups are often left displaced or deprived of their livelihood as a result of climate change adaptation planning. As such, they end up paying a disproportionately high price for climate change adaptation, especially given that they are generally not the major contributors to climate change emissions to begin with, and will often not be reaping the immediate benefits of living in a climate-proof city (Anguelovski et al., 2016; Lanza & Stone, 2016; Liao, Chan, & Huang, 2019; Mitchell, Enemark, & van der Molen, 2015; Shi et al., 2016). For example, a new coastal protection plan may make fishing grounds inaccessible to a coastal community while protecting a planned commercial district that will cater to high-end businesses and global lifestyle customers. Such developments lead to further marginalization of already marginalized groups.

The environmental justice movement has only just begun to systematically frame the disproportionate impacts of climate change as a justice issue. The present absence of strategies and goals for justice in climate adaptation planning is highly problematic. It is imperative to ask the question: to which populations does climate change pose the largest risks?[1]

We believe that diverse voices need to be included in climate change adaptation planning. Most environmental justice work in urban planning has focused on distributional justice or the recognition that injustices are spatial and can be mapped. However, procedural justice involving those affected in the planning process itself has been far less addressed, and is of critical importance. A truly just planning process that is open, inclusive, and has diverse voices at the table can help ensure that everyone benefits from living in a climate-proof city.

But how do we make it happen; how do we get more voices at the table while ensuring effective steering of the project? This is a question that many of us ask ourselves. Since the TNOC Summit provided us with a diverse group of experts and practitioners in the field, we decided to take this opportunity and pose the question there. We imagined that gathering people from all over the world, actively living and working in cities that each have their own adaptation strategies, would result in a process of learning from and with each other, furthering the dialogue on justice in adaptation planning.

The Paris session

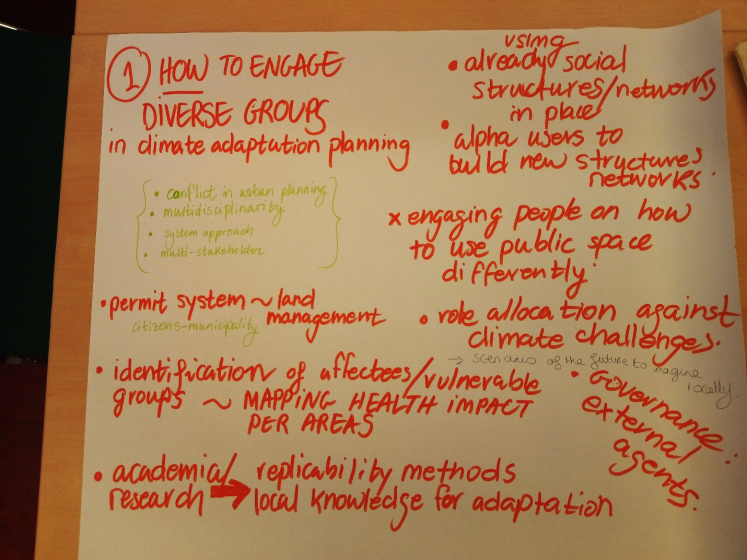

The aim of our session at the TNOC Summit in Paris was threefold: to create a dialogue around justice in climate adaptation planning, to collect good examples and best practices as well as common pitfalls and lessons learned, and to explore opportunities for collaboration. We invited participants to think along and share their experience around three questions:

- How to engage diverse groups in climate adaptation planning? (incl. bottom-up initiatives and top-down policy)

— How do you know who to engage? And at what stage of the process?

— How do you actively engage them? - What is the role of governance and how may it need to shift? (Local and international, incl. regulatory frameworks)

- How to transfer and learn between places? (tools, methods, approaches)

|

|

|

Images by Marthe Derkzen

The question: How to engage?

“Walk and talk together. Don’t go sit in a room.”

Using scenarios as a top-down strategy for community engagement can be linked and combined with the bottom-up approach of design by community. People know best what is needed and desired for their community. They can outline the desired requirements for residents to live safe, healthy, and happy lives. This could look like a pedestrian-friendly urban district equipped with schools, gardens, shops and services, a playground, a library, bike lanes, and restaurants. A place where people go for work, study, and recreation and one that encourages people to meet each other. Or maybe the community rather wishes a quiet residential neighborhood within easy reach of public transport. Within these desired requirements, residents, city planners, and designers can co-create adaptation pathways: how can we adapt the physical, social, economic, and cultural environment so that it can deal with likely climate change impacts? In such a process, awareness and understanding of climate change impacts and adaptation options are very helpful – and can be supported by scenarios. The other way around, scenarios can be “ground truthed” by having them imagined locally. How do you imagine your own future? And how do you imagine your future living in this city with regular heatwaves and flooded public spaces? Imagining scenarios of the future is a promising method to feed in local knowledge and desires while generating support for climate adaptation planning (Iwaniec et al., 2020).

This links to something else that was brought up during the session as a requirement for inclusive adaptation planning: creating a level playing field. Common knowledge and understanding contribute to a level playing field, for example in a design workshop in which all parties base their input, feedback, and ideas on the same set of facts or descriptions. Of course, a legal counselor or a stormwater engineer may know more about specific procedures or construction techniques compared to a resident who is a language teacher, but the idea here is that everyone at the table feels enabled to purposefully contribute to the discussion. Respecting and valuing each party’s expertise, whether that is in engineering or in knowing the ins and outs of a neighborhood (favorite spots and underused areas, vulnerable families, or key persons), is also crucial for creating a level playing field. A shared belief that all the voices present are needed for a successful project (and that no voices are missing) means that everyone’s voice is heard and respected. One pitfall here is that oftentimes such workshops are part of participatory planning processes in which some parties are being paid as part of their job while others are expected to engage on a voluntary basis. It would be worthwhile to invest in new planning experiments, such as paying community representatives for their contributions, that can further level the playing field.

Who to engage

But how do you know who to engage? In the session, four types of stakeholder groups were highlighted. First, are those living in vulnerable neighborhoods in terms of climate change impacts. These can be residents living at the riverbank or near the coast but also those living in very stony neighborhoods where temperatures rise quickly and rainfall has a hard time infiltrating the soil, impacting their health and wellbeing. Mapping area-specific impacts on health, property, and loss of livelihood should be a first step in the identification of affected groups. Second, are those affected by climate adaptation planning, for instance, the fishing community that is no longer allowed to enter their former fishing grounds because a sea wall was built to protect the downtown area from flooding, turning the waters into a bay which is now being used as a recreational harbor. Third, are the “alpha users” or “champions” in a community who attract community involvement and act as spokespersons. They build and sustain local networks, can encourage action, build momentum, and are not to be confused with community leaders. Fourth, are the most “violent” i.e. those who are most resistant to the plan and who may protest against its implementation. Rather than ignoring this group, they should be invited to participate early on, not just to avoid conflict or delay, but because their reasons to resist the adaptation planning process are grounded in their experience as active, knowledgeable, and vocal residents. Tensions are allowed to happen; different people have different views. What we can agree on in a planning process for future impacts, are the boundaries of what can and cannot happen.

And how do people become engaged? Session participants came to speak about community meals as a clear bottom-up example of citizen engagement. In the community of Doorn, where Marthe Derkzen (MD) used to live, a midday meal is served every Wednesday to older and often lonely residents, cooked by the local butcher, and using the City Hall’s public library community house as a venue. Those eating pay the equivalent of $US10 for a three-course meal plus coffee. It is wonderful to see grey-haired citizens dropping in one by one, arriving an hour ahead and staying up to an hour late. The social function of this weekly community meal is unrivaled. And it extends beyond a joyful get together; while working on this TNOC piece in the library, MD witnessed how one of the older men offered his services as a tire repairman to a library employee (a bicycle tire, of course, in this Dutch case). Getting up slowly from the sofa, bent over, he came to walk more and more upright on the way to the job to be fixed. In MD’s former Amsterdam neighborhood, children experiencing difficulties in learning at school are learning how to cook and run a restaurant serving weekly meals to fellow residents. And in MD’s current home, Arnhem, citizen-led urban agriculture initiatives are combined with community cooking clubs in vulnerable neighborhoods. Indeed, community meals come in many shapes, are common worldwide, and are appreciated for their strong social power. Their established social structure can be used for informative and engagement sessions around a variety of topics (as they do in Doorn) and can serve as a best practice example to set up a similar structure for engagement around urban development and adaptation planning.

Community meals are an example of community-led initiatives supported by local businesses and local government. According to several groups in our session, this is the way to go in adaptation planning: alter the way of thinking and have communities in the lead, supported by other organizations. A challenge here is to establish sufficient trust between bottom-up and top-down actors, for instance, trust to leave responsibilities to the other.

“Let top-down support bottom-up efforts.”

Recommendations for inclusive engagement

Participants in our session pointed out several recommendations to improve the processes of engagement and co-creation. First of all, local governments are encouraged to utilize existing social structures. Participants urged city planners to take advantage of existing community events and networks rather than creating new forums, as it turns out to be much more effective to work within existing structures (see community meals example). “One-time engagement is a waste of time.”

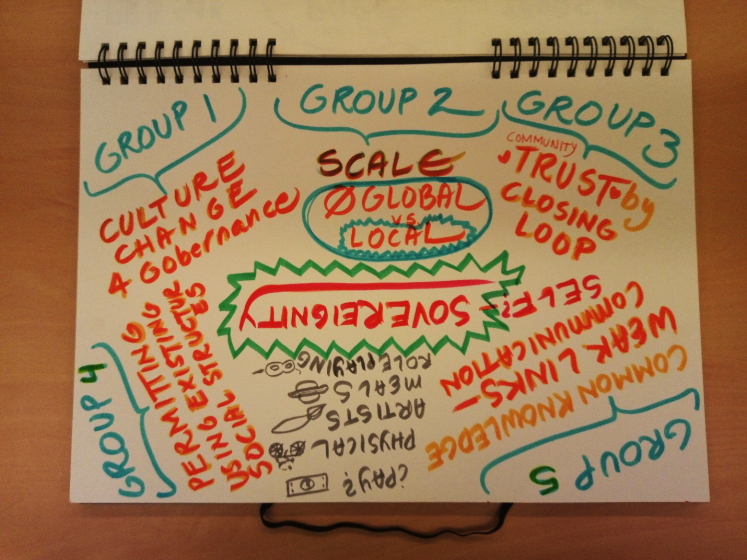

Governance and knowledge transfer

Our session also asked questions about governance and how knowledge is shared and transferred. We found that also here, much attention was given to collaborative, multi-actor efforts. Some participants suggested that a shift in governance is necessary, one in which communities take the lead and one that allows time for transition as the building up of required skills. Yet, in rethinking governance for adaptation planning, there is a certain tension between the perception of climate change as a long-term, global, and complex issue versus the often locally felt urgency of adaptation measures. This led us to a discussion about scale: at what scale can participatory decision-making processes work, and at what political level in a multi-layered governance system? How can they best be managed, and by whom? Here, power asymmetries come into play. Huda Shaka (HS) provided the example of her hometown Dubai where contractors and consultants are the main actors in adaptation planning, operating in a governance system without any legal requirements for community engagement.

In the Netherlands, new legislation is making citizen participation an obligatory step in urban planning. A pitfall here is that the meaningfulness of people’s participation will be dependent on the degree to which the process is a safe and level playing field for all parts of the community. Instead of developing a relatively rigid regulatory framework that identifies key players in adaptation planning from the outset, perhaps it is worth considering a governance shift which focuses first and foremost on creating an enabling and inclusive planning process and engagement environment.

Our third question was: how can we transfer learnings between places? Several ideas surfaced in the group discussions, from an inventory of best and worst practices to linking people via national citizen science. Compared to the first two questions, there was a clear and shared perception of the prominent role of science and scientists when it comes to learning and transferring knowledge for adaptation. We spoke about the replicability of methods and developing a library of case studies—indicating the need for a systematic approach. At the same time, participants stressed that local knowledge can and should inform adaptation planning. In our eyes, this reveals the challenge of combining different knowledge systems for shared learning and practice.

To conclude, some reflections

The session identified a number of challenges for inclusive adaptation planning: getting people to commit to something not yet clearly defined, the difficulty of prioritizing and reconciling conflicting viewpoints (which has implications for the trust that underpins projects), social vulnerabilities, “weak links” such as communication from a key individual to the community, the vulnerability of networks built on personal relationships, and multiple existing knowledge systems. Is our world one where inclusive engagement could be a reality?

Luckily, there are different stories of which some were told during our session. Stories such as Paris’ permit system for green streets and the payment of community leaders. And there are plenty of positive and practical ideas for including diverse voices adaptation planning:

- role-playing for climate adaptation and resilience

- public lecture series

- art for awareness: artists’ role in community activation

- day-in-a-life experiences

- joint fact-finding: step back until you find something to agree upon

- meet at a “third” place, neutral for all involved

- develop inclusive planning guidelines e.g. C40 Cities guidelines

What stood out for us as organizers is that the session participants, in their groups, appeared to have interpreted the “engagement of diverse groups in climate adaptation planning” as the engagement of residents, and diverse groups thereof, in municipal planning processes. It is interesting to observe that those who are generally considered as key stakeholders, i.e. public and private sector, researchers, and non-profit parties, were mostly left out of the discussion. One assumption could be that by focusing on diversity, inclusion, and justice, we geared the discussion towards the representation of some of the less usual suspects such as marginalized groups. Participants’ affiliation with these groups may also be the reason why our first question on engagement attracted noticeably more interest than our second and third question on governance and transferability/learning, respectively.

We should also reflect on the term engagement itself. Engagement may have become associated with official institutions, e.g. local governments, engaging others, e.g. residents, in their planning and decision-making processes. One group even hinted that engagement can be framed as public education. With such an interpretation, engagement may indicate certain power dynamics: residents may give their opinion at an information evening or in a consultation round, so that they have “participated” in the process, but there is no guarantee (or it may not have been the intention) that their voices are being heard and taken into account, actually shaping the process and outcomes.

Rather than constructing knowledge and shaping ideas together, the participation process is perceived as one of the many boxes to be ticked in the municipal planning cycle. This is not what we meant by engagement — we were looking for the engagement of diverse groups with each other. By not specifying or stressing beforehand what we mean with engagement, we may have unintentionally pushed the discussion in the direction of a uni-directional, “top-down” paradigm of engagement: i.e. adaptation planners engaging with community actors as part of a formal process.

There seems to be a gap between what academics perceive as true (meaningful and inclusive) engagement and how engagement is happening in reality. Where we envision a just representation of all affected voices that builds on existing structures in a long-term process that all parties perceive as pleasant, the reality is one of pushed engagement, checked boxes, and hurried change.

We hope to see the discussion on inclusive engagement in climate adaptation planning become more prominent and to see some of the promising positive ideas become reality in all of our cities.

Marthe Derkzen, Timon McPhearson, Huda Shaka, Marion Lacourt and Frida Larios

Arnhem/Nijmegen, New York, Jeddah City, Paris, and Washington

References

Anguelovski, I., Shi, L., Chu, E., Gallagher, D., Goh, K., Lamb, Z., … Teicher, H. (2016). Equity Impacts of Urban Land Use Planning for Climate Adaptation. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 36(3), 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16645166

Iwaniec, D. M., Cook, E. M., Davidson, M. J., Berbés-Blázquez, M., Georgescu, M., Krayenhoff, E. S., … Grimm, N. B. (2020). The co-production of sustainable future scenarios. Landscape and Urban Planning, 197, 103744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103744

Lanza, K., & Stone, B. (2016). Climate adaptation in cities: What trees are suitable for urban heat management? Landscape and Urban Planning, 153, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.12.002

Liao, K. H., Chan, J. K. H., & Huang, Y. L. (2019). Environmental justice and flood prevention: The moral cost of floodwater redistribution. Landscape and Urban Planning, 189, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.04.012

McPhearson, T., Iwaniec, D. M., & Bai, X. (2016, October 1). Positive visions for guiding urban transformations toward sustainable futures. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.004

Mitchell, D., Enemark, S., & van der Molen, P. (2015). Climate resilient urban development: Why responsible land governance is important. Land Use Policy, 48, 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.05.026

Shi, L., Chu, E., Anguelovski, I., Aylett, A., Debats, J., Goh, K., … Van Deveer, S. D. (2016). Roadmap towards justice in urban climate adaptation research. Nature Climate Change, 6(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2841

[1] (risk= hazard * exposure * vulnerability)

about the writer

Timon McPhearson

Dr. Timon McPhearson works with designers, planners, and local government to foster sustainable, resilient and just cities. He is Associate Professor of Urban Ecology and Director of the Urban Systems Lab at The New School and Research Fellow at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies and Stockholm Resilience Centre.

about the writer

Huda Shaka

Huda’s experience and training combine urban planning, sustainable development and public health. She is a chartered town planner (MRTPI) and a chartered environmentalist (CEnv) with over 15 years’ experience focused on visionary master plans and city plans across the Arabian Gulf. She is passionate about influencing Arab cities towards sustainable development.

about the writer

Marion Lacourt

Marion Lacourt is an illustrator, an engraver and by extension a filmmaker. Her film Sheep, Wolf & a Cup of Tea… ( Emile Reynaud Price 2019) got selected in multiple festivals : Locarno, Clermont-Ferrand, Annecy, New-York, Chicago, Aswan, Hong Kong, Berlin, Cork, Moscou, Bilbao, Barcelone …

about the writer

Frida Larios

Frida Larios [b. San José, Costa Rica, 1974 (of Salvadoran parents)] has been leading learning since 2000, following her higher purpose of facilitating interpretative visual narrative applied to authored books, artworks, garments, workshops, and dialogues with children, youth, and designers, bridging the stories from Indigenous peoples and lands to contemporary reflection and appreciation, through her award-winning New Maya (Visual) Language coding methodology.

Leave a Reply