Repenser la protection de la nature dans le contexte des Objectifs du Développement Durable en articulant action locale et régionale avec les politiques nationales et internationales

Aujourd’hui, les zones de nature ordinaire — parfois appelées paysages productifs — sont les plus menacées par la pollution, par des systèmes d’exploitation non durables, mais aussi par notre négligence.

Un constat sans appel

Sur la base des listes rouges produites par l’UICN, le Chief scientist de l’IUCN, Thomas Brooks alerte sur le rythme sans précédent de l’érosion de la biodiversité auquel nous assistons. Nous savons également qu’alors que notre subsistance dépend pour 95% de sols cultivés, 52% d’entre eux sont dégradés ou terriblement dégradés. C’est dans ce contexte, alors que la première partie du dernier rapport du GIEC vient d’être rendue publique, que va s’ouvrir à Marseille, le Congrès mondial de la Nature. A cette occasion, lors de l’Assemblée de ses membres, l’UICN se prononcera sur la possible adhésion des collectivités locales à l’Union. Ce Congrès s’inscrit sur la route qui relie Edimbourg à la 15ème Conférence des Parties à la Convention sur la Diversité Biologique (CoP15 de la CBD) et au 7ème Sommet Mondial de la Biodiversité des Gouvernements Locaux et Infranationaux, à l’heure où les discussions sur le renouvellement, le renforcement des plans d’actions des gouvernements infranationaux, des villes et des autres autorités locales vont bon train.

Pour préparer le Congrés de l’UICN, quatre webinaires ont été organisés avec le soutien du projet Post 2020 Biodiversity Framework – EU support, financé par l’Union européenne et mis en œuvre par Expertise France, et de l’Office Français de la Biodiversité (OFB). Ils se sont tenus les 22, 23, 29 et 30 juin, chacun correspondant à une thématique.

Des territoires de nature ?

Les trois premiers webinaires traitent des différents types de territoires[1] du point de vue de la nature qui les recouvre. Ils s’intéressent à la nature en termes d’actions à conduire par les gouvernements locaux et infranationaux pour la protéger, la maintenir en bon état et la restaurer quand elle est trop dégradée.

1. Les territoires de nature exceptionnelle

Les territoires de nature exceptionnelle sont tous ceux qui font l’objet d’une protection. Quand les premières protections sont mises en place à la fin du XIXème siècle, on voit déjà que ce qui les motive est lié aux usages. Ainsi, la première zone de nature protégée au monde, est Fontainebleau en 1861, où est créée une réserve artistique – pour que les Peintres de Barbizon puissent continuer de capturer la beauté du monde et la fixer sur une toile. Vient ensuite Yellowstone en 1872, le premier parc national créé pour protéger cette étendue de toute exploitation et prédation. Depuis plus d’un siècle, ces espaces recouvrent une surface de plus en plus importante. Leur gestion nous en apprend tous les jours sur le fonctionnement du vivant. Ce sont des espaces « pilotes », des « laboratoires » où l’on apprend à protéger la nature, à en prendre soin, à la restaurer aussi.

Des témoignages des intervenants disponibles ici ressortent trois enseignements majeurs :

a) Protéger durablement les espaces naturels remarquables nécessite de prendre en compte tous les besoins des personnes qui vivent sur ces territoires. Ainsi en est-il de la fréquentation touristique, qui doit être encadrée pour maintenir un équilibre durable entre préservation de la nature et emploi pour les populations locales. C’est également vrai pour les espaces verts de la Ville du Cap qui veille à associer les citadins dès la conception de ses projets urbains.

b) Pour être efficaces, les labels de protection les plus prestigieux, décernés par des organes ou institutions internationaux devraient prévoir d’associer plus étroitement et de façon pérenne les gouvernements infranationaux à même de mettre en place les modes de gestion pragmatiques permettant d’encadrer la fréquentation des sites ou leur accessibilité par exemple.

c) Quand les gouvernements infranationaux sont impliqués dans la protection des espaces remarquables, les protéger créée une dynamique pour l’ensemble du territoire. Ainsi en est-il de la Ville de Saint François qui, partant de la protection du site de la Pointe des Châteaux, a engagé une politique de protection de la nature qui dépasse le seul périmètre de ce lieu remarquable.

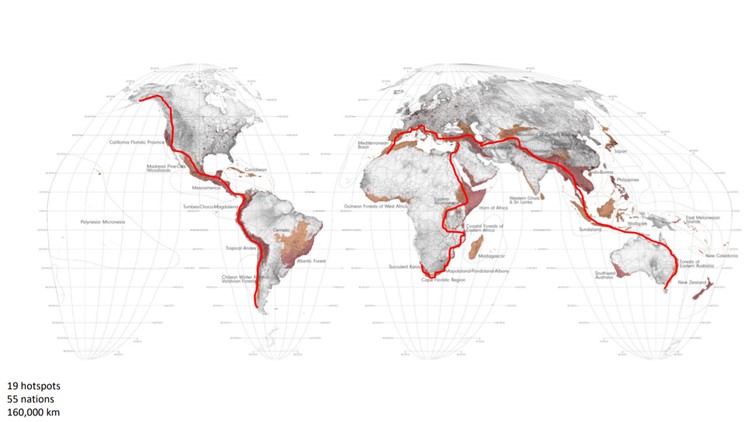

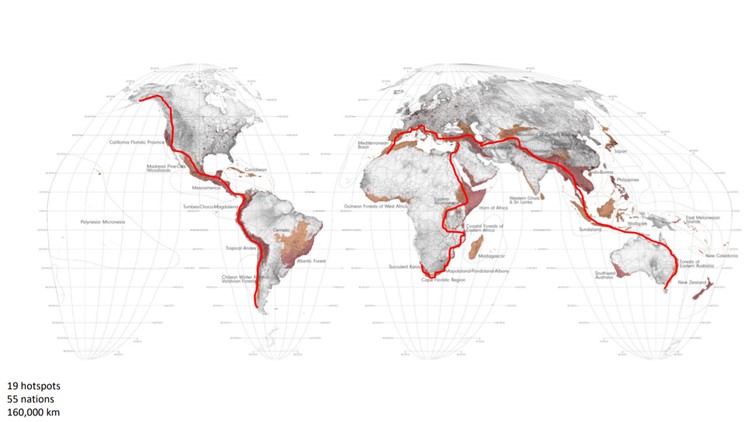

Toutefois, la rapidité avec laquelle le changement climatique affecte les écosystèmes planétaires impose d’accélérer la reconnexion des espaces naturels protégés. Richard Weller, titulaire de la Chaire Meyerson d’urbanisme à la Weitzman School of Design de l’Université de Pennsylvanie, souligne ce paradoxe : alors que les humains ont déployé des trésors d’intelligence pour assurer leurs déplacements et ceux de leurs biens et marchandises, la connexion des espaces protégés est inexistante, interdisant aux espèces tout déplacement. Tandis que nous nous sommes fixés comme objectif de protéger 17% des aires terrestres avec les cibles d’Aichi, Richard Weller rappelle qu’il existe aujourd’hui 867 zones protégées dans le monde. Ensemble, elles représentent environ 15% de la surface terrestre, soit une différence de 1 ou 2% avec l’objectif fixé. Toutefois, ce sont autant d’archipels isolés les uns des autres. A travers le projet de Parc Naturel mondial, le chercheur propose de créer une ligne du nord au sud du continent américain (la « Pataska », allant de la Patagonie à l’Alaska), une autre de la Libye à l’Afrique du Sud, et une troisième du Maroc jusqu’à l’Asie centrale et l’Australie. Ces trois lignes permettraient de regrouper 19 des 36 hotspots, ce qui recouvre 55 nations et 160 000 km au total. Ce nouvel ensemble constituerait un parc naturel mondial : le « World Park Project ». Ces lignes rouges pourraient devenir des chemins de randonnée et former une sorte d’infrastructure verte : des routes ou des chemins dans une ville pourraient mener à des parcs, conduisant à des zones cultivées puis à des zones protégées, etc.

Dans la vision de Richard Weller, il ne s’agit pas simplement de zones de promenade ou de randonnée, mais aussi d’espaces où l’on peut travailler, amener les gens à voir ce qu’il se passe – à l’inverse des parcs naturels tels qu’on les concevait autrefois, dont les visiteurs étaient exclus. Ce parc naturel mondial ne vise pas à renforcer les zones protégées actuelles mais à protéger celles qui se situent dans les zones intermédiaires, sur lesquelles nous devons travailler pour pouvoir restaurer les connexions – et de le faire à l’échelle mondiale pour lutter contre la crise climatique. Cette vision originale conduit à repenser les deux autres types de territoire que nous avons identifiés : les territoires urbains et ceux de « nature ordinaire ».

2. Les territoires urbains

En effet, à l’autre bout du spectre, se trouvent des espaces qui nous ont permis de nous affranchir des aléas de la nature. Il s’agit des espaces urbains. Depuis le début de ce siècle et les premiers effets du changement climatique, la demande de nature en ville s’accentue et conduit à un vaste mouvement qui voit nos villes et nos grandes métropoles se verdir. Mais aussi — parce que ces zones urbaines s’étendent et accueillent une part croissante d’une population mondiale qui va augmentant — ces espaces urbains viennent empiéter sur les espaces de nature protégés et leur empreinte affecte toutes les zones du globe.

Travaillant actuellement avec un réseau de 33 villes situées sur des territoires de zones « à risque », Richard Weller a réalisé une cartographie précise indiquant à quels endroits exactement la ville – ou ses infrastructures – va entrer en conflit avec la biodiversité. Selon lui, l’objectif n’est pas de stopper le développement de ces villes mais plutôt de le concevoir en l’orientant vers certaines zones de façon à en éviter, contourner d’autres pour maintenir les continuités écologiques nécessaires à la préservation de la biodiversité. Le chercheur nous invite à une autre vision des villes et de la nature, où les unes et l’autre se développent en symbiose et non en opposition : « Il va falloir reprogrammer le développement urbain pour que les villes entrent en symbiose avec leur habitat et ne soient plus des parasites. Nous n’avons pas d’autre choix que de planifier et de concevoir un autre développement urbain et de rendre des comptes à tous types de vie sur Terre. »

Des témoignages des intervenants, il ressort que les villes pèsent d’un poids de moins en moins soutenable sur l’ensemble des écosystèmes de la planète. Et les inégalités se creusent : l’accès à la nature dans les villes les plus riches est inégalement réparti. Le développement anarchique des villes dans les pays du Sud menace des zones de biodiversité remarquables, indispensables au bon fonctionnement de l’ensemble des écosystèmes qui constituent ces espaces urbains. Les plus démunis sont aussi ceux qui vivent dans les environnements les plus dégradés. Toutefois, depuis le début de ce siècle, la prise de conscience qu’un autre modèle est possible gagne du terrain. Quatre points donnent des raisons d’espérer :

a) La mobilisation des réseaux de collectivités locales, des ONG, des citoyens, des élus et des gestionnaires pousse nombre de villes à agir. Diagnostic partagé, planification urbaine privilégiant la création et l’accès aux espaces verts, gestion différenciée de ces espaces de nature en ville, désartificialisation et renaturation des sols, mise en place de dispositifs favorisant le retour des espèces de flore, de faune (dont les pollinisateurs) en ville se développent.

b) Pour gagner encore en efficacité, la collaboration entre les municipalités et les acteurs privés – ie. entreprises, commerces, ensembles d’habitation, etc. – permet de gagner de nouveaux espaces verts sans étendre encore la surface des villes notamment par la végétalisation des toits, des murs ou l’ouverture au public d’espaces verts privés. Réglementations encourageant les pratiques vertueuses, labels, référentiels se mettent en place et concourent à une dynamique positive.

c) Certaines municipalités travaillent déjà à élargir leur action au-delà de leur territoire pour aider les agriculteurs à produire de façon plus soutenable, en encourageant l’agriculture bio, à préserver la ressource en eau.

d) Parce qu’elles accueillent une part croissante de la population, que ce sont des lieux de culture, d’innovation et d’échanges, c’est aussi dans les villes que peuvent advenir les solutions qui permettront l’avènement d’une véritable civilisation écologique à travers la mise en place des solutions fondées sur la nature.

3. Les territoires de nature ordinaire

Entre les espaces protégés et les villes, il reste ce qui fait l’essentiel des écosystèmes de notre planète : qu’en France nous appelons la « nature ordinaire ». Cette nature est dite « ordinaire » parce qu’elle est commune – au sens où elle n’est pas « rare ». Par ce terme on désigne aussi bien les champs cultivés que les forêts ou les déserts. C’est ce qui n’est pas protégé, pas défini comme « exceptionnel » mais qui n’est pas non plus de l’urbain. Aujourd’hui, ce sont les espaces les plus menacés par les changements d’usage, la surexploitation, le changement climatique, la pollution, etc. et ce, également à cause de notre négligence.La concentration de la population dans les villes nous conduit à les déserter, et ce faisant à les délaisser alors même qu’ils nous fournissent notre nourriture, l’eau, l’air, l’essentiel de nos ressources.

Tous les intervenants se sont accordés sur l’urgence à protéger ces espaces qui assurent le maintien de notre vie sur terre et sont pourtant aujourd’hui mis en grand danger par nos pratiques, notamment agricoles. La difficulté à les nommer – le concept de « nature ordinaire » est difficile à traduire en anglais : le terme utilisé « productive landscape » n’en désigne qu’une partie est à mettre en regard de notre difficulté à les gérer durablement.

a) La nécessité de repenser entièrement notre agriculture ne pourra se faire qu’en articulant action locale et globale. Il s’agit par exemple de revoir à la fois les pratiques agricoles et l’organisation même des marchés et nos modes de consommation pour réduire la part de produits animaux et le gaspillage de denrées alimentaires. Pour cela, il faut sortir de la logique des politiques « en silo » : articuler production agricole et protection de la nature. Plus globalement, repenser tous nos systèmes d’exploitation des ressources naturelles pour qu’ils ne détruisent pas irrémédiablement nos écosystèmes, ce à quoi nous invitent les objectifs du développement durable (ODD).

b) Les gouvernements locaux et infranationaux sont moteurs dans la restauration des écosystèmes de nature ordinaire pour le bénéfice des populations qui y vivent et en vivent.

c) Plus encore que pour les aires protégées, la mobilisation de tous les acteurs est indispensable à la protection effective de cette nature ordinaire qui participe à la préservation de la nature extraordinaire. Chacun doit s’y atteler en fonction de ses compétences et ses moyens. Aucune entreprise ne peut considérer cela comme accessoire.

Systèmes de financement et gouvernance ?

S’il est évident que la préservation d’un espace de nature protégé ne relève pas des mêmes règles, ni du même type de financements que ceux qui utilisés pour gérer les espaces verts en ville, les zones agricoles, l’océan, les déserts ou les forêts par exemple, la nature est UNE, et tous ces types de nature s’entrecroisent, s’entremêlent.

Aussi, le quatrième et dernier volet de cette série a-t-il été consacré aux questions de finance et gouvernance. Les gouvernements infranationaux sont aux avant-postes du combat contre le changement climatique et pour la biodiversité : ils sont proches d’une population en demande de nature, d’une population qui prend conscience que nous ne pouvons pas continuer à sacrifier notre futur et celui de nos enfants à un présent de plus en plus incertain, d’une population qui supporte de plus en plus mal d’être la victime de l’exploitation intensive, des pollutions, de tout ce qui dégrade notre environnement. C’est peut-être ce qui conduit les gouvernements infranationaux à innover, à proposer des solutions qui sont ensuite reprises par les États nationaux et les institutions internationales. Ainsi, rappelons-nous qu’une des toutes premières Obligations Vertes – les fameux Green bonds – a été lancée – en 2001 ! – par la ville de San Francisco pour financer la mise en œuvre d’un vaste plan d’installation d’énergie solaire – en réponse à la crise énergétique qui touchait alors la Californie. Les obligations vertes sont aujourd’hui mises en œuvre par les états et remportent un vrai succès.

Cependant, les questions de financement ne peuvent pas être considérées indépendamment des questions de gouvernance. Plus que jamais, les décisions des uns impactent le devenir des autres. Les effets du changement climatique causent plus de morts au Sud qu’au Nord alors même que le Sud n’est que marginalement responsable des émissions de gaz à effet de serre. Que va-t-il se passer quand les glaciers de l’Himalaya, troisième réservoir planétaire d’eau douce qui alimentent les principaux fleuves d’Asie : Indus, Gange, Brahmapoutre, Mékong, (Yangtsé), Fleuve jaune – vont disparaître ? La vie de près d’un tiers de l’Humanité en dépend.

Aussi, pour le futur de l’humanité, nous ne pouvons laisser les seuls pays riches accéder aux financements. Edgar Morin nous le rappelle : « la crise climatique, l’érosion de la biodiversité rappelle à la grande famille humaine la communauté de destin qui est la sienne. » Les questions de gouvernance et de finance sont étroitement liées. L’accès aux financements pour les gouvernements infranationaux est facilité quand il s’inscrit dans des coopérations avec leurs Etats, les institutions ou projets régionaux, ou encore en lien avec le privé.

Tous les intervenants partagent le même constat résumé en 4 points :

a) Nos modèles de développement ne sont pas durables, ils épuisent nos ressources naturelles.

b) La crise climatique met en danger nos économies au nord comme au sud.

c) Changer de modèle suppose des investissements massifs. Les plans de relance post-Covid constituent une réelle opportunité pour investir dans la réalisation d‘infrastructures vertes et bleues.

d) Les villes, en particulier, doivent se saisir de cette opportunité pour mettre en œuvre les solutions fondées sur la nature et recréer ainsi les emplois perdus pendant la pandémie.

En termes de financement, quatre leviers doivent être actionnés concomitamment pour relever ce fantastique défi :

a) Des réformes politiques : l’organisation des marchés, les réglementations et les critères d’attribution des aides et subventions n’encouragent pas le financement des infrastructures vertes et bleues, des systèmes de production durables ou des solutions fondées sur la nature.

b) Un renforcement de la coopération entre gouvernements infranationaux et secteur privé : Les solutions fondées sur la nature, les infrastructures vertes et bleues comme les systèmes de production durable nécessitent d’être conçus et mis en œuvre localement. En ce sens, les gouvernements infranationaux sont bien placés pour proposer leur mise en œuvre. Mais bien souvent, leur accès aux financements est limité par le montant de leurs demandes de crédits, considéré comme trop faible pour accéder aux fonds délivrés par les bailleurs publics. Une piste consiste pour les gouvernements infranationaux à renforcer leurs coopérations avec le secteur privé pour solliciter les bailleurs publics.

c) Un accroissement du nombre de projets réellement et durablement vertueux : si les projets liés à la production d’énergies renouvelables sont bien documentés et techniquement murs, ce n’est pas encore le cas pour les solutions fondées sur la nature, les infrastructures vertes et bleues ou les modes de production durable. Il existe un réel besoin de connaissances sur les bénéfices tirés à moyen et long terme de la mise en œuvre de ces innovations. Les gouvernements infranationaux constituent des territoires d’expérimentation qui pourraient gagner à coopérer avec les entreprises et la communauté scientifique.

d) Des synergies accrues entre le niveau de gouvernance infranational et mondial pour combiner changements de modes de production et de consommation avec les nécessaires réformes de l’organisation des marchés.

Mettre en œuvre ces leviers nécessite également une réforme de gouvernance qui articule étroitement l’action locale et les politiques nationales et globales, la recherche d’un équilibre entre systèmes politiques centralisés et décentralisés, à travers le concept développé par Bob Jessop et rappelé par Gaël Giraud de « Colibration ». Ce concept définit l’apprentissage d’une « collaboration » qui soit en même temps une « calibration », à savoir la recherche permanente d’interactions intelligentes et adaptées aux décisions, entre échelle locale et échelles centrales – étatiques et internationales. Retrouver de la « directionnalité » en politique sans réduire de manière artificielle la complexité des interactions entre société, économie et biodiversité, tel est selon Gaël Giraud le premier des grands défis de gouvernance que nous devons relever. Autre grand défi concernant l’administration des biens communs telle que définie par Elinor Ostrom – la biodiversité, comme la santé, en est un – la recherche de « méta-règles » qui s’imposent en cas de désaccord, afin d’arbitrer les conflits en conservant l’objectif défini ensemble auparavant.

Réconcilier 100% de l’humanité avec notre planète

Meriem Bouamrane, responsable scientifique du Programme MAB de l’UNESCO, nous rappelle que la pandémie de COVID 19 ouvre une période de transformation invitant à revoir notre relation à la nature, aux autres, à nos modes de vie et façons de travailler. Elle offre également des opportunités de financement sans précédent. Toutefois, et tous les intervenants l’ont souligné, nous ne pourrons relever ces défis qu’ensemble. Ensemble… Cela suppose de tenir compte des besoins de chacun, de casser les politiques opérant en silo qui perdurent malgré la feuille de route fixée collectivement avec les Objectifs du Développement durable, de penser la préservation de la biodiversité, toute la biodiversité, en cherchant dans le même temps à créer un futur plus juste, plus solidaire.

Pour ce faire, nous ne pourrons nous passer de la force extraordinaire d’action qui est celle des gouvernements locaux et infranationaux dont Christophe Nuttal, Directeur du R20, nous rappelle qu’ils détiennent 75% des solutions en termes de lutte contre le changement climatique. La Convention pour la Diversité biologique a été pionnière. Comme nous l’a rappelé Oliver Hillel, elle a été la première à reconnaître leur rôle aux côtés des Etats dans la lutte contre l’érosion de la biodiversité et l’utilisation durable des ressources naturelles. Puisse la CoP15 de la CBD nous donner les moyens de renforcer et d’institutionnaliser cette nécessaire coopération.

Stéphanie Lux, Elisabeth Chouraki, and Ingrid Coetzee

Paris, Paris, et Cape Town

Rethinking Nature Protection in the Context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by Linking Local and Regional Action with National and International Policies

Today, areas of ordinary nature — sometimes referred to as productive landscapes — are the most threatened by pollution, by unsustainable exploitation systems, and also by our negligence.

A Clear Statement

Based on the IUCN red list, the IUCN Chief Scientist, Thomas Brooks, warns of the unprecedented rate of biodiversity loss we are witnessing. We also know that while 95% of our livelihoods depend on cultivated soils, 52% of them are degraded or severely degraded.

It is within this context, while the first part of the latest IPCC report has just been made public, that the World Conservation Congress will open in Marseille. On this occasion, during the Assembly of its members, IUCN will decide on the possible membership of local authorities in the Union.

This Congress is part of the road between Edinburgh and the 15th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CoP15 of the CBD) and the 7th Global Biodiversity Summit of Local and Subnational Governments, an official parallel event to the COP, at a time when discussions on renewing and strengthening the action plan on sub-national governments, cities, and other local authorities are well underway.

In preparation for the IUCN Congress, four webinars were organized with the support of the Post 2020 Biodiversity Framework – EU support project, financed by the European Union and implemented by Expertise France, and the French Office for Biodiversity (Office Français de la Biodiversité -OFB). They were held on June 22, 23, 29 and 30, each corresponding to a relevant theme.

Diverse Domains of Nature

The first three webinars deal with the vast differences between lands and territories from the point of view of the natural landscapes that cover them. They focus on nature in terms of actions to be taken by local and sub-national governments to protect it, maintain it in good condition, and restore it when these lands are degraded.

1. Exceptional Nature

The lands and territories of the natural world which are exceptional or indispensable are all those which are most often needing to be subject to protection. Protective conservationist policies have a long history. The very first set of protections were put in place at the end of the 19th century and were predominantly motivated by a desire for them to be used. For example, the first protected natural area in the world was Fontainebleau in 1861, where an artistic reserve was created so that the Barbizon painters could continue to capture the beauty of the world for all to see through their paintings.

Then came Yellowstone in 1872, the first national park ever created to protect this area from exploitation and predation. For more than a century, these protected areas have been growing in size. Our management of these areas teaches us about diverse ways of life in nature. They can act as “pilot” areas or “laboratories” where we learn to protect nature, to take care of it, and to restore it too.

From the testimonies of the webinar participants, we can draw three important lessons:

a) Sustainably protecting exceptional natural areas requires taking into account all the needs of the people who live in and around these areas. When it comes to traffic on account of tourism, for example, this must be controlled to maintain a sustainable balance between nature conservation, and employment for local populations. This is also true for the green spaces of the City of Cape Town, which is careful to involve city dwellers right from the outset of its urban projects.

b) Prestigious protection labels, awarded by international bodies or institutions, should provide for a closer and more permanent involvement of sub-national governments, which are able to put in place pragmatic management methods to control the use of natural area sites and their accessibility, for example.

c)When sub-national governments are involved in the protection of exceptional natural spaces, protecting them creates dynamic benefit for the entire region. This is the case for the City of Saint François, which, starting with the protection of the Pointe des Châteaux site, has initiated a nature protection policy that goes beyond the perimeter of this remarkable place.

The rapidity with which climate change is affecting planetary ecosystems makes it necessary to accelerate the reconnection of protected natural areas. Richard Weller, Meyerson Chair in Urban Planning at the Weitzman School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania, points out the paradox that while humans have been very apt at driving connections and networking human life, technology, goods, and cargo, protected areas suffer from disconnection making it impossible for species to move and migrate, in some cases. While we have set ourselves the goal of protecting 17% of terrestrial areas with the Aichi targets, Richard Weller reminds us that there are currently 867 protected areas in the world. Together, they represent about 15% of the Earth’s surface, which is a difference of 1 or 2% with the target.

However, these protected lands are like archipelagos in that they are isolated from each other. With the World Natural Park project, Weller proposes we create lines of connection that could alleviate this problem. For example, a pathway running from north to south on the American continent (the “Pataska”, from Patagonia to Alaska); another running from Libya to South Africa, and a third from Morocco to Central Asia and Australia. Just these three pathways would bring together 19 of the 36 hotspots, covering 55 nations and 160,000 km in total. This new ensemble of pathways could constitute a world natural park: the “World Park Project”. These pathways could become hiking trails and form a kind of green infrastructure: roads or paths in a city could lead to parks, leading to cultivated areas and then to protected areas, etc.

In Weller’s vision, these are not just areas for walking or hiking, but also spaces where you can work, and gather – unlike some traditionally conceived conservation and protected areas, where visitors are often excluded. This world nature park does not aim to reinforce the current protected areas but to protect those teleconnections in between, which we need to work on to ultimately protect earth’s ecosystems and habitats from extinction. Moreover, to do so on a global scale to additionally fight this threat that has only increased due to the climate crisis.

This original vision leads us to rethink the two other types of lands and territories we have identified: urban environments and those of ordinary nature.

2. Urban Environments

Apart from exceptional nature, on the other side of the spectrum, the urban environment is a vastly different space. Since the beginning of this century, and with the first effects of climate change, the demand for nature in the city has increased and led to a vast movement that is working ever harder to make our cities and major metropolises greener in an effort to curb global warming and other effects of climate change. Due to the fact that urban areas are expanding and a rapidly increasing share of the world’s growing population now lives in cities – these urban spaces are encroaching on protected nature areas, and their footprint is affecting all areas of the globe.

Currently working with a network of 33 cities located in “at risk” areas, Richard Weller has produced a precise map showing exactly where the city – or its infrastructure – will conflict with biodiversity. According to him, the objective is not to stop the development of these cities but rather to design it by orienting it towards certain zones in order to avoid or bypass others in order to maintain the ecological continuities necessary for the preservation of biodiversity. Weller invites us to imagine another vision of cities and nature, where both develop in symbiosis and not in opposition. Weller says, “We will have to reprogram urban development so that cities enter into symbiosis with their habitat and are no longer parasites. We have no choice but to plan and design a different kind of urban development and be accountable to all types of life on Earth.”

From the testimonies of the speakers, it is clear that cities are weighing more and more unsustainably on the planet’s ecosystems as a whole. And inequalities are growing: access to nature in the richest cities is unevenly distributed. The often-informal development of cities in the countries of the South threatens remarkable areas of biodiversity, which are essential to the proper functioning of all the ecosystems that make up these urban areas. The poorest people are also those who live in the most degraded environments. However, since the beginning of this century, awareness that another model is possible has been gaining ground.

Three points give us reason for hope:

a) The mobilization of local government networks, NGOs, citizens, elected officials, and managers is pushing many cities to act. Shared diagnoses, urban planning that favors the creation of and access to green spaces, differentiated management of these natural spaces in the city, reconstituting soils, and setting up systems that encourage the return of species of flora and fauna (including pollinators) to the city are all developing. To gain even more efficiency, collaboration between municipalities and private actors – i.e. companies, businesses, housing estates, etc. – makes it possible to gain new green spaces without the need for big budgets.

b) To gain further efficiency, collaboration between municipalities and private actors – i.e. companies, businesses, housing estates, etc. – makes it possible to gain new green spaces without extending the surface of the cities, in particular through the greening of roofs, walls, or the opening of private green spaces to the public. Regulations encouraging ecological practices, labels, and reference systems are being put in place and contribute to a positive dynamic.

c) Some municipalities are already working to extend their action beyond their territory to help farmers produce in a more sustainable way, by encouraging organic farming, to preserve water resources. Because they are home to a growing share of the population and are places of culture, innovation, and exchange, it is also in cities that solutions can be found that will allow the advent of a true ecological civilization through the implementation of nature-based solutions.

3. Ordinary Nature

Between protected areas and the cities, there remains another essential part of our planet’s ecosystems: which in France we call “ordinary nature”. This nature is called “ordinary” because it is part of most people’s common experience. Such nature is not rare or remarkable; people encounter it every day. This may include cultivated fields, as well as forests or deserts, depending on the landscape and lands of that region. It is what is not protected, not defined as “exceptional” but which is not urban either. Today, these are the spaces that are most threatened by changes in use, overexploitation, climate change, pollution, and also by negligence. The concentration of a growing population in cities leads us to desert them, and in so doing to neglect them, even though they provide us with our food, water, air, and most of our resources.

All the speakers agreed on the urgency of protecting these spaces which ensure the maintenance of our life on earth and which are increasingly endangered by our practices, especially agricultural. The concept of “ordinary nature” is difficult to translate into English: the term “productive landscape” is another common usage, but only designates a part of what the term ordinary nature encompasses. Important points that resulted include:

a) The need to completely rethink agricultural practices can only be done by articulating local and global action. For example, it is necessary to review both agricultural practices and the very organization of markets and our consumption patterns to reduce the share of animal products and food waste. To do this, we must break out of the logic of “silo” policies: articulate agricultural production and nature protection. More globally, we need to rethink all our natural resource exploitation systems so that they do not irreparably destroy our ecosystems, which is what the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) invite us to do.

b) Local and sub-national governments are driving the restoration of ordinary ecosystems for the benefit of the people who live in and from them.

c) Even more than just for protected areas, the mobilization of all stakeholders is essential for the effective protection of ordinary nature, which contributes to the preservation of extraordinary nature. Everyone must work on this according to their skills and means. No company can consider this as an accessory.

Financing systems and governance?

The preservation of a protected nature area does not fall under the same rules, nor the same type of financing as those used to manage green spaces in the city, in agricultural areas, or the ocean, deserts, and forests, for example. Yet, all of these ecosystems are connected and nature is ONE, so all of these types of nature intertwine, and intermingle. Therefore, the fourth and final part of this series was devoted to the issues of finance and governance. Sub-national and local governments are at the forefront of the fight against climate change and for biodiversity: they are close to a population in demand for nature, a population that is becoming aware that we cannot continue to sacrifice our future and that of our children to an increasingly uncertain present, a population that is increasingly resentful of being the victim of intensive exploitation, pollution, and everything that degrades our environment. This is perhaps what leads all levels of sub-national governments to innovate, to propose solutions that are then taken up by national states and international institutions. Thus, let us remember that one of the very first Green Bonds was launched – in 2001! – by the City of San Francisco to finance the implementation of a vast solar energy installation plan – in response to the energy crisis that was affecting California at the time. Green bonds are now being implemented by states and are proving to be a real success. However, financing issues cannot be considered in isolation from governance issues. More than ever, the decisions of some affect the future of others. The effects of climate change cause more deaths in the South than in the North, even though the South is only marginally responsible for greenhouse gas emissions.

What future do we want?

What will happen when the Himalayan glaciers, the third largest reservoir of fresh water in the world, which feed the main rivers of Asia: Indus, Ganges, Brahmaputra, Mekong, (Yangtze), Yellow River – disappear? The lives of nearly a third of humanity depend on it.

Also, for the future of humanity, we cannot let richer countries alone have access to financing. Edgar Morin reminds us that “the climate crisis and the erosion of biodiversity remind humanity of its common destiny.” The issues of governance and finance are closely linked. Access to financing for sub-national governments is facilitated when it is part of cooperation with their states, regional institutions or projects, or in connection with the private sector.

All the speakers drew the following collective conclusions:

a) Our development models are not sustainable, they exhaust our natural resources.

b) The climate crisis is endangering our economies in the North and in the South.

c) Changing our model requires massive investments. The post-Covid recovery plans are a real opportunity to invest in green and blue infrastructure.

d) Cities, in particular, must seize this opportunity to implement nature-based solutions and thus recreate the jobs lost during the pandemic.

In terms of financing, four levers need to be activated concomitantly to meet this fantastic challenge:

a) Policy reforms: the organization of markets, regulations, and criteria for granting subsidies and grants do not encourage the financing of green and blue infrastructure, sustainable production systems, or nature-based solutions, are not enough alone.

b) Strengthening cooperation between all levels of sub-national governments and the private sector: Nature-based solutions, green and blue infrastructure, and sustainable production systems need to be designed and implemented locally. In this sense, subnational governments are well-positioned to design their implementation. But often, their access to funding is limited by the size of their loan applications, which are considered too small to access funds from public donors. One approach is for sub-national governments to strengthen their cooperation with the private sector to solicit public donors.

c) An increase in the number of truly and sustainably ecological projects: while projects related to renewable energy production are well documented and proven to be technically feasible, this is not yet the case for nature-based solutions, green and blue infrastructure, or sustainable production methods. There is a real need for knowledge on the medium and long-term benefits of implementing these innovations. Sub-national and local governments are territories of experimentation that could benefit from cooperation with businesses and the scientific community.

d) Increased synergies between the sub-national and global levels of governance to combine changes in production and consumption patterns with the necessary reforms in market organization.

Implementing these levers also requires a reform of governance that closely articulates local action and national and global policies, the search for a balance between centralized and decentralized political systems, through the concept developed by Bob Jessop and recalled by Gaël Giraud of “Colibration”. This concept defines the learning of a “collaboration” that is at the same time a “calibration”, i.e. the permanent search for intelligent interactions adapted to decisions, between local and central scales – state and international. According to Gaël Giraud, the first of the major governance challenges we must meet is to rediscover “directionality” in politics without artificially reducing the complexity of interactions between society, the economy, and biodiversity. Another major challenge concerning the administration of common goods as defined by Elinor Ostrom – biodiversity, like health, is one of them – is the search for “meta-rules” that can be imposed in the event of disagreement, in order to arbitrate conflicts while preserving the objective defined together beforehand.

Reconciling 100% of humanity with nature

Meriem Bouamrane, Chief scientist of the programme MAB UNESCO, reminds us that the COVID-19 pandemic opens a period of transformation inviting us to rethink our relationship with nature, with others, with our lifestyles, and our ways of working. It also offers unprecedented funding opportunities. However, as all the speakers emphasized, we can only meet these challenges together. Together… This implies taking into account the needs of everyone, breaking down policies operating in silos that persist despite the roadmap set-out collectively with the Sustainable Development Goals, thinking about the preservation of biodiversity, all biodiversity, while at the same time seeking to create a fairer, more united future.

To do this, we cannot do without the extraordinary force of action of local and sub-national governments, of which Christophe Nuttal, Director of the R20, reminds us that they hold 75% of the solutions in terms of the fight against climate change. The Convention on Biological Diversity was a pioneer. As Oliver Hillel reminded us in one of the webinars, the convention was the first to recognize the role of subnational governments alongside States in the fight against biodiversity loss and the sustainable use of natural resources. May the CoP15 of the CBD give us the means to strengthen and institutionalize this necessary cooperation.

Stéphanie Lux, Elisabeth Chouraki, and Ingrid Coetzee

Paris, Paris, and Cape Town

about the writer

Elisabeth Chouraki

Elisabeth Chouraki coordinates the Post-2020 Biodiversity Framework – EU support project implemented by Expertise France and funded by the European Union.

about the writer

Ingrid Coetzee

Ingrid has more than 30 years’ experience in sustainability and governance. Her work focuses on mainstreaming nature, its benefits, and nature-based solutions into urban planning and decision-making in cities and city regions thereby helping them become healthier, and more resilient and liveable places.

Leave a Reply