As urban practitioners, it’s important to understand the significance of these city rankings and indices, how they may or may not be useful, and be clear and mindful of their limitations.

So, what happens when a city reaches the top ranks? Have you ever noticed the kind of media attention the city gets? City rankings are indeed very popular and attract a lot of media attention across the globe.

Each year, there are more than 40 city indices published globally. In fact, since 2007, more than 500 different urban indices and rankings have been published worldwide to rank cities from across the globe according to the Business of Cities. These indices show how cities perform when compared with each other in their region or globally based on various indicators including livability, quality of life, competitiveness, sustainability, prosperity, resilience, and others. As urban practitioners, it’s important to understand the significance of these city rankings and indices, how they may or may not be useful, and be clear and mindful of their limitations.

In addition, there are not many rankings that specifically focus on the environment, despite the clear role that cities play amidst the current climate and biodiversity crises. In a recent post on the ecological performance of cities, IUCN and NParks Singapore address this shortcoming by presenting two indices that intend to measure urban nature in cities and set targets towards a nature-positive future. While the City Biodiversity Index has been around for a while, it has recently been revised to improve its robustness and applicability. The other index, IUCN Urban Nature index, which measures the ecological performance of cities, has recently launched its draft and the ongoing pilots in 5 cities will soon provide important insights on its application. Yet, how does one define usability? Or usefulness? And for whom?

In this post, we present the preliminary findings from our research on city rankings and indices, exploring who are the users of city rankings, and how they use rankings in practice. We also identify the limitations of city rankings and propose future prospects and recommendations. Our findings are based on multiple sources of information, including desktop research, literature review, and interviews conducted with the index publishers, urban practitioners, and academic experts.

Who are the users of city rankings and how is it useful for them?

Based on our research, we have considered three main categories of users for city rankings, i.e., a) city ranking producers (including real estate, consulting firms) b) city policymakers and urban planners, and c) researchers and students. Each of them uses city rankings in a different manner and we do acknowledge that there may be other users existing as well.

a) City ranking producers

a) City ranking producers

City rankings constitute a useful dataset for producers. For example, The Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Global Livability index and the MERCER’s Quality of living index are useful for the parent company’s core business and advising other MNCs in assessing relocation of workers and their remuneration. On the other hand, Resonance’s Best Cities Index and Savills Resilient Cities Index use it for advising clients on future real estate investment decisions for multinationals.

Similarly, global consultancy firms, such as ARUP and Arcadis, use city rankings as a useful resource for branding and marketing for their own firms. One such example is the ARUP’s City Resilience Index and the framework which is often used by the firm for other projects. On the other hand, Grosvenor, which is one of the largest privately-owned international property companies, produces information that can be used directly for the corporate’s own real estate investments and market visibility.

b) City policymakers, urban planners, and local authorities

City rankings are also used by policymakers for city planning and benchmarking. For example, some cities use their city ranking to benchmark against the best, or at least higher ranked cities and set goals, and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). One such example is the Global Power City Index used by Tokyo city to set goals and annual KPIs, based on the performance of different indicators each year.

Similarly, there are also various theme-based rankings, for example, transport-related rankings which assess the transport infrastructure in cities and rank them according to public transportation availability, accessibility, and infrastructure provisions for sustainable transport. These rankings help make comparisons on various parameters and inspire other cities to learn from. One such example is the Walking Cities ranking by Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) which inspires cities to promote active mobility in cities, thus promoting a healthy air quality environment and cutting transport emissions.

Some cities also use it for domestic comparison, i.e., to assess how different cities are performing at the national or regional level. This is the case for the Global Power City Index used in the United Kingdom or the smart city rankings/ Swachh Bharat Mission (Clean India Initiative) used by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs in India.

City policymakers and local investment authorities often use the city rankings strategically for city branding, communications or to publicize the good work the city administration is doing (based on different indicators). For example, EIU’s livable cities index has ranked Melbourne as the world’s most liveable city repeatedly for seven years (consecutively from 2011-17), uses it to promote tourism, and attract foreign direct investments (FDIs). Similarly, Singapore (which is ranked high on the Mercer index) is used by EDB, the Economic Development Board of Singapore, agency responsible for investment promotion publicizing Singapore’s 1st rank in Asia for quality of living.

c) Researchers and Students

City rankings provide access to datasets for researchers. Recently, there has been a steep rise in interest in research on the role and performance of cities in addressing resilience and sustainability issues. City rankings potentially allow researchers to access new data for an individual city, collected and processed by third-party producers. These new data can be used to learn about urbanization trends, including theme-based indicators to understand best practices, e.g., for transport, water, or the environmental and social performance of cities. One such example is the UESI index that offers an interactive tool to compute environmental and social indicators for various cities.

What are some of the limitations to city rankings?

Despite their potential benefits, city rankings do have quite a few limitations. It is important for policymakers, local authorities, and researchers to be mindful of such limitations and consider them whenever necessary.

Lack of available, accessible, and quality data for assessment. One of the main limitations to city rankings is the lack of quality data available to calculate the index or ranking. Often, city rankings are based on open data sources, and not based on datasets which are officially disclosed or recognized by the city authorities. This lack of data seriously limits the scope of the analyses. For most of the cities, the city-level data are not consistently available and differs drastically. Even if data is publicly available, we usually don’t have information on the way these data are collected, and it may differ from country and city. For example, while making a city-to-city comparison, data may be available for the London city area but, for Tokyo, data might be available only for the metropolitan area.

In addition, in some cities from developing countries, city-level data may be outdated, and the only available data might be from national-level authorities, but updated years ago. Due to financial constraints, most of the cities from the Global South are often unable to update their city-level data annually or make it public, thus missing out on being assessed for city rankings. Conversely, cities from the developed nations of Europe and North America ensure that there is publicly available data, and therefore data accessibility is much easier in these cities. This leads to a clear bias towards the Global North in the majority of city rankings. Therefore, it is important for policymakers to be aware of the potential biases due to data availability when deciding to make use of a city ranking for their own city.

Lack of representation of secondary cities. Relatedly, the method of city selection is rarely explained by the producer of rankings. Most of the cities selected are primarily based on openly available data for cities, a determining factor to include any city in the indices. Some producers also use other available resources to select the city e.g., the Global Power City Index includes cities based on the top 20 major city rankings from Global Cities Index (GCI), Cities of Opportunity, and the Global Financial Centers Index (GFCI). It is more often observed that city rankings focus only on global cities, leading to repetition of the usual suspects at the top and secondary cities not making to the index, thus more often ignoring them.

Disaggregating city-level data. Spatial aspects of a city are important to understand the urban form (sprawl, green space), the geographical situation of the city (natural assets, isolation, connectivity), and others. Hence, spatial datasets are important to determine livability in cities. It is observed that more often the detailed spatial data for cities from the global south is unavailable. As a result, city indices publishers are unable to incorporate spatial data sets in their indicators. It is understood that this could be due to limited resources or publicly available data sets for the producers of these rankings.

Similarly, the neighborhood-level data is more often ignored or not publicly available and captured in these rankings. In cities, neighborhoods are the real essence of city-making, but the producers of city rankings rarely use such nuanced, sub-city-level data. This clearly limits the use of such rankings for urban design and livability purposes.

Lack of (representative) public engagement. Another limitation of city rankings is that they are rarely engaging with the local public. Ideally, publishers of city rankings would understand how an individual city is perceived and lived by the residents, but it is also important to engage them at some point during the city assessment. Even though some of them claim to engage with the city residents, few indices disclose how the public opinion is accounted. Those that do, even suggest a lack of representativity, e.g., EIU the Global Livability Index which is constructed based on subjectively measured data (i.e., data based on the opinion of someone else and relies on the opinion of those creating/capturing the data which are essentially the EIU employees in a particular city). Similarly, IMD-SUTD Smart City Index (SCI) assesses 118 cities worldwide by capturing the perceptions of only 120 residents in each city, which is quite small as a sample size. Almost all the city indices that we came across are based on publicly available secondary data and only a few of them consult the residents, local city authorities, or academia to have their views.

Lack of involvement of academia. Other than a few city rankings which are peer-reviewed by experts from academia, most of the rankings miss out on this expertise. It is often observed that there is an oversimplification of indicators included in the indices and collaborations with academic experts could indeed provide a more integral view of city rankings to guide the index results and suggest improvements.

Lack of transparent methodology. Often, the methodology of city indices is not disclosed publicly or available free of cost. It usually comes with a paid subscription service that policymakers, researchers, or the general public may not be willing to pay for. This leads to misinterpretation of the methodology or the city ranking and interest only on the final ranking instead of fully understanding the detailed methodology or indicators used by the indices.

Lack of learning for other cities. It is also observed that city rankings typically attract attention for winning or losing cities, meaning cities that are ranked at the top or at the bottom. This could be because of the way producers showcase best to worst performing cities, rather than listing them in a way that could trigger learning for cities.

What are the prospects for city rankings in the future?

Overall, we find that, while city rankings are potentially useful for different users, they also come with limitations and constraints which need to be addressed for better outcomes.

First, city ranking publishers need to make sure that there is transparency and a clear indication of the methodology used in city rankings. As mentioned earlier, if the methodology is available publicly without any paid subscription, there could be a better understanding and response to the rankings.

Secondly, city rankings should not just focus on ranking the cities but, in fact, should also indicate ways of improvement or learning for other cities. This could help in having city collaborations and engagements to improve different themes or indicators lacking in respective cities.

Thirdly, in general, the visual appeal of these rankings can be more informative, visually enticing, and insightful with the possibility to change some of the user preferences while exploring these rankings.

In addition, we identify some of the prospects for city rankings and where they could particularly be useful.

Stimulating Public interest for the city residents: Generally, extreme rankings tend to stimulate public interest in urban policymaking. Once a city ranking is published, the individual performance of that city generates media attention and recognition (or shame!) in the regional and local media. With the rise in public participatory planning approaches in cities, these rankings may be starting points for city-wide discussions between the experts, residents, and local authorities, to how their city can be improved in specific indicators.

Addressing the demand for Environmental Indicators in Global Indices: With the rise in climate change and biodiversity issues, there is a renewed interest in indices and rankings that include environmental indicators. To our knowledge, no existing city ranking covers all the important environmental or nature-related aspects, including the use of nature-based solutions for biodiversity and climate change. However, the recently launched Urban Nature Index by IUCN Urban Alliance promises to be a new knowledge product helping cities measure and track their ecological performance and sets a benchmark in measuring the environmental performance of cities. Increasing the amount of easily accessible environmental indicators and testing their robustness will help guide cities towards better environmental practices.

Developing theme-based vs Overall city indices: More generally, we note that cities are made of complex urban systems, and it is important to understand them individually and in-depth while ranking the cities. Therefore, we recommend city rankings to be more targeted and meaningful by focusing on theme-based city benchmarking rather than trying to cover all the aspects and losing the fine ingredients present in these themes.

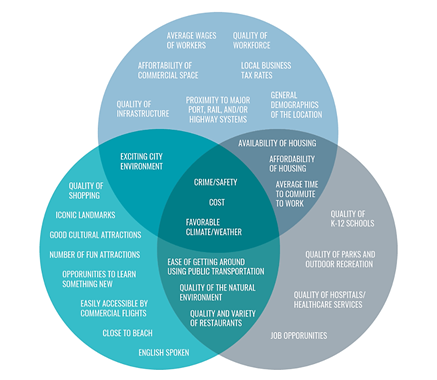

For example, the Walking Cities Index by ITDP is an extremely specific index focused on walkability whereas the Best Cities ranking by Resonance considers transportation as a whole (Fig 4. below), but misses out on an important form of transportation in the city, i.e., walkability. In fact, it only considers ease of getting around using public transportation in the city which is just one part of overall transportation in the city. City ranking producers must be transparent in the themes or sub-themes they assess.

Guidance for these themes can be obtained from the Sustainable Development Goals, which represent a useful guideline for cities: not only Sustainable Development Goal #11, which provides specific targets for cities, but also all other goals that are, in one way or another, related to urban governance.

Incorporating retrospective and prospective dimensions: Given the importance of scenario exploration in urban and environmental governance, indices could also consider future scenarios to consider city trajectories. Based on the city action plans, climate change commitments, and future plans for cities, projections can be made, and they can be ranked for the next 10, 20 years. This could generate greater interest, learning, and invite policymakers from other cities to make better commitments or plans in their cities.

Learning for other cities: It is important for city rankings to initiate learning for other cities. Some good examples that city rankings could take inspiration from are, the Urban Environment and Social Inclusion Index (UESI), or the CDP climate scores who don’t focus on showcasing the top and the bottom cities, but are arranged in a format that promotes comparison of cities as well as allows for improvements or learning for other cities.

Our exploration of city indices is still at the beginning, but our preliminary findings agree with other scholars that, in fact, city rankings should be Taken more Seriously. They have the potential to promote healthy competition and guide cities to nature-positive futures, and it’s up to us urban practitioners, to design or interpret them in the most useful way possible.

For the interviews conducted during this research, we would like to thank the team of Global Power City Index, led by Hiromi Jimbo, Norio Yamato, and Peter Dustan from the Mori M Foundation. We would also like to thank the authors of essay – Taking City Rankings Seriously – Daniel Pejic and Michele Acuto from the University of Melbourne. We also appreciate the time for the short discussion with Angel Hsu (author of Urban Environment and Social Inclusion Index) and Agnieszka Ptak-Wojciechowska, Anna Januchta-Szostak (author of publication – ‘The Importance of Water and Climate-Related Aspects in the Quality of Urban Life Assessment’) for taking out time to answer my questions about city rankings.

To read more on this topic, here are some of the reference papers if you are interested to know more about city rankings.

- TAKING CITY RANKINGS SERIOUSLY: Engaging with Benchmarking Practices in Global Urbanism by Michele Acuto, Daniel Pejic, Jessie Briggs

- ON LIVABILITY, LIVEABILITY AND THE LIMITED UTILITY OF QUALITY-OF-LIFE RANKINGS by Brian W. Conger

- Review of Concepts, Tools and Indices for the Assessment of Urban Quality of Life by Shilpi Mittal, Jayprakash Chadchan, Sudipta K. Mishra

Devansh Jain and Perrine Hamel

Singapore

about the writer

Perrine Hamel

Perrine is an Assistant Professor at NTU’s Asian School of the Environment. Her research group examines how green infrastructure can contribute to creating resilient and inclusive cities in Southeast Asia. Prior to joining NTU, Perrine was a senior scientist at Stanford University with the Natural Capital Project.

Leave a Reply