Quite often city-makers who want to implement nature-based solutions run into many hurdles standing in the way of realising their green ideals. But how do you tear down those walls? Effective co-creation is a path forward.

More than half of the world’s population lives and works in diverse, bustling cities. And perhaps, if you are reading this blog, you have a desire to make these places we call home greener—it can be done with nature-based solutions! Quite often city-makers who want to implement nature-based solutions run into many hurdles standing in the way of realising their green ideals. In this blog, DRIFT intern and Connecting Nature project member Shibeal McCann shares how adaptability and communication can help to overcome these hurdles collectively.

During an enlightening session (“Building natural networks and delivering the deal with stakeholders”) at the Glasgow Innovation Summit (23-25 March), I heard experiences from the cities of Glasgow, Genk, and A Coruña, as they endeavoured to explore how to deliver city-scale green networks using nature-based solutions.

We heard three contrasting examples, yet a coherent story on governance with unifying themes emerged—of adaptability and communication. Each city initiated networks to achieve a common vision that could not have been achieved alone. We heard firsthand the trials, tribulations, and triumphs of building networks to deliver the deal with stakeholders. Knowledge was shared that has relevance beyond the region and context it came from. We discussed insights into how to build networks in our own work. What stood out is that delivering parks is by no means a walk in the park. Here are the lessons I took away from this session.

Lesson #1: Strike the right tone

While building networks between people and places is encouraged, it is not easy, as explicit knowledge and textbooks on the topic are few and far between. As project manager, Max Hislop presented the hardships faced when he and his team set out to develop the Glasgow Clyde Valley (GCV) Green Network Blueprint, Scotland, UK.

Their journey from development to delivery began over fifteen years ago. The GCV Network blueprint is a strategic master plan which seeks to turn Glasgow City Region ‘green’ by developing green networks. The master plan includes installing walking and cycling routes to break up the conurbation (high density of buildings) of Glasgow while leaving room for wild spaces to return to for wild animals. Three cheers for Glasgow’s response to the biodiversity and climate emergency we are facing!

In all this, communication is key. You need to speak the language of your partners in the process and avoid complex data. The GCV team learned this the hard way when they presented a detailed, integrated habitat model mapping the networks of species to urban planners. It flew over the crowd’s head. The team had to accept that data is only effective if it can be communicated properly to the audience in question. This setback forced them to adapt, and, since then, they’ve started discussing this topic with urban planners in a shared language, linking the model to the project’s overarching strategic development plan.

Key take-home: Communicate with planners, if you have strong simple graphics, people will make use of them, avoid complex data – simpler is easier to absorb and digest.

Lesson #2: Find a banner to unite under

Nature-based solutions work better when people and organisations collaborate to achieve what they could not attain alone. Working in partnerships helps to ensure that different needs are considered and local opportunities are exploited.

This state of mind led the city of Genk, Belgium, to form partnerships to deliver their Stiemerdeals. Mien Quartier unveiled the innovative ways in which her city involved stakeholders, including citizens, groups, and local citizens – developing a network of people within their project.

https://www.genk.be/stiemerdeals

The Stiemer itself is a stream running through the city of Genk, physically connecting neighbourhoods, nature reserves, and strategic city sites. Since 2015, the city has started revitalising the neglected and polluted valley to realise its full potential. What initially began as a spatial and ecological transformation project, later evolved to include social and economic objectives, realising that these types of transformations could act in synergy.

So, what do these deals entail? The city of Genk collaborates with one or more local entrepreneurs and companies with a flexible approach to governance. Every Stiemerdeal is a tailor-made cooperation, a symbiotic relationship. Stiemer honey, beer, biscuits – you name it, together they’ve made it. In total, they made 37 deals within the first year, incorporating a huge diversity of entrepreneurs into the valley!

The Stiemerdeals offers partners both financial support and material support. At the start of the deal, the team co-creates a clear vision, for how one aspect of the valley can become a valuable asset for the city and deliver multiple benefits. It’s an innovative way to develop a flexible approach to engage people and organisations, give them a sense of ownership, and make them feel part of something bigger, creating a snowball effect.

For me, the key take-home message here is that complex objectives usually cannot be achieved by a city alone. We must increase the capacity to realise the full potential of nature-based solutions. By connecting and networking, and co-producing innovative business models we can accelerate the journey to reach the multiple goals of nature-based solutions together with local actors.

Lesson #3: Tear down those silos

For our final lesson, we took a trip to the North-West of Spain, to the city of A Coruña, where Antonio Prieto González shared their process for working with urban gardens in the region.

The various benefits of urban gardens were apparent in his city from the outset, specifically as powerful tools for fostering social cohesion, bonding between generations, and ownership of public spaces.

The team in A Coruña didn’t have much experience with nature-based solutions at the start of their adventure. And there were other ongoing initiatives in the city — school gardens, private urban gardens, and community gardens — however, they were all disconnected. The team wanted to create a network to unite these similar initiatives because siloed government departments are one of the main barriers to achieving multi-functional benefits. Many different departments in the municipality were connected indirectly and directly to these urban gardens, like the education, employment, and environment department.

But how do you tear down those walls??

Their solution was combining two societal levels: organisational and strategic. Antonio and the team took the time to work both levels when delivering the urban gardens and simultaneously making interdepartmental connections to show that there is common ground.

Firstly, they organised meetings with relevant councillors and heads of the departments to secure political support. This enabled them to connect to the operational level, working with technicians from different departments. They needed both.

Once again, the process wasn’t a breeze — some departments were not so easy to contact; it’s hard to find the right people (who have to have the time and energy and are not always the first people you think of) -but it’s crucial when working in this horizontal manner.

The key lesson for me was that working on fenced-off projects isn’t enough. You need to align the goals and benefits of the nature-based solutions with the wider city goals. In order to achieve this, making connections from one team to another, and one project to another, is vital to create and build local alliances.

Reflections

To me, these three contrasting examples form a coherent story on governance. Each city initiated networks to achieve a common vision that could not be achieved otherwise, employing communication, adaptability, and operational versus strategic working.

I saw a testbed for what does and doesn’t work so well, revealing the dead ends encountered so that, for others, the journey will be shorter. In that way, this session was an excellent way to show the variety of governance innovations we work on in the Connecting Nature project, and beyond!

About connecting nature

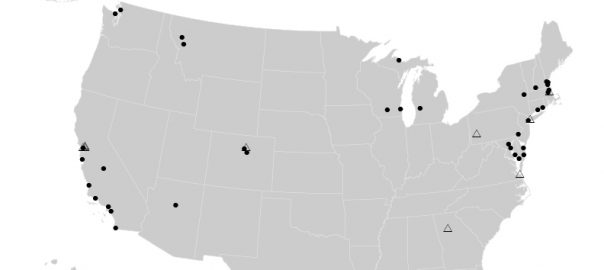

Coordinated by Trinity College Dublin, Connecting Nature is a consortium of 30 partners within 16 European countries, and hubs in Brazil, China, Korea & The Caucasus (Georgia and Armenia). We are co-working with local authorities, communities, industry partners, NGOs, and academics who are investing in the large-scale implementation of nature-based projects in urban settings. We are measuring the impact of these initiatives on climate change adaptation, health and well-being, social cohesion, and sustainable economic development in these cities. We are also developing a diversity of innovative actions to nurture the start-up and growth of commercial and social enterprises active in producing nature-based solutions and products. Connecting Nature is funded under the Horizon 2020 program (call SCC-02-2016-2017; Grant Agreement 730222) and includes 29 partners and 5 self-funded partners.

DRIFT’s team is coordinating the co-production of a new planning cycle with the involved cities and academic partners based on state-of-the-art knowledge about co-production and reflexive monitoring. This planning cycle is for city planners and policymakers that will connect experimentation and lessons to ongoing policy and market needs. It includes operational mechanisms to accelerate the scaling of nature-based solutions as well as guiding principles for turning socio-economic and institutional barriers into opportunities. This is achieved by close interaction between the academic and city partners; to learn by doing and to iteratively reflect upon the steps that are being taken in ongoing nature-based solution projects.

https://drift.eur.nl/nl/publicaties/three-lessons-for-co-creating-nature-based-solutions/

Shibeal McCann, Marleen Lodder, Paula Vandergert, Kato Allaert

Dublin, Rotterdam, London, Rotterdam

about the writer

Lodder Marleen

Marleen Lodder graduated MSc Architectural Engineering at Eindhoven University of Technology with honours in 2010 and worked as a Ph.D. candidate (October 2011-2015) at DRIFT, Erasmus University. Her research focuses on how urban area development in the Netherlands can become beneficial, by generating economic, ecologic, and social cultural values.

about the writer

Paula Vandergert

Dr Paula Vandergert is a Senior Research Fellow in the Sustainability Research Institute, University of East London. She works with local authorities, strategic development organisations and local community groups on adaptive governance methods for sustainable and resilient communities and places.

about the writer

Kato Allaert

Kato Allaert is a green urbanist, currently based in the Netherlands. In her work, sustainable cities with happy citizens are the focal point. To achieve this, Kato links the spatial perspective with the social, economic and ecological aspects of cities. Kato has around 10 years of work experience in different contexts – from academic research to urban design practice and the public sector – and in different countries – the UK, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Belgium.

Leave a Reply