Although, not without controversy, Assisted Migration is one tool in a larger toolbox of strategies that can be aided by more transdisciplinary collaboration as we work toward building resilience in and around our cities. It presents unprecedented and exciting opportunities.

In April of 2022, the New York Times ran a viral piece on its front page entitled Trying Everything, Including Lettuce, to Save Florida’s Beloved Manatees. It details a sordid tale of Floridian Manatees — sea cows — struggling for survival amid a riverine habitat polluted by industrial effluents and agricultural and stormwater runoff that was choking out the seagrass upon which they rely.

It spoke of an experiment that would be funny if it weren’t so tragic, of well-intentioned scientists and citizens dumping tons of romaine lettuce into local waterways as a last-ditch effort to curtail mass starvation events. It’s not every day that aquatic vegetarian mammals are graced with front page coverage in the Times, but it’s precisely these kinds of stories that are likely to persist in one form or another as we hurdle deeper into the 21st century. Perhaps even more than the memetic images of starving arctic polar bears clinging for dear life atop melting ice rafts, accounts of charismatic megafaunal plight in our own backyards seems to pluck at heartstrings in particularly visceral ways, and implore us to action.

Yet, somehow immediately, another image came to mind―not of emaciated sea cows, but that of an upside-down Black Rhino, blindfolded and dangling precariously from a helicopter as it hurdles toward a distant horizon. These are images depicting the early stages of another grand experiment―the Assisted Migration (AM) of species from one place to another.

In the case of the critically endangered African Black Rhino, it entails a one-way trip for groups of selected individuals to various partner sites across South Africa with the goal of extending their range to well-suited and lesser-poached locales. Early data for the Black Rhinos are promising, with the WWF accounting for a 21% increase in South African populations since 2003. In the case of the starving Floridian manatee, it might conceivably entail a search for congruous aquatic habitats elsewhere in the US; For example, in and around the port of Galveston, TX, where, by all accounts, the seagrass is thriving by comparison.

But would they survive such a trip? Who would pay for it? Who would benefit? Would it be socially, ecologically, and politically viable? And what about the unanticipated problems of adjustment on both sides?

These are just a few of the complex questions that are implied by Assisted Migration (AM), an emerging practice for human-led adaptation. Contemporary examples of AM extend beyond just fauna to include many beloved or economically valuable plants and trees whose historic range is becoming untenable. Proponents of AM argue that if climate or anthropogenic pressures prove too high for a species to survive in situ, it may be possible to help them move to new, less risky locales. AM is controversial because it often conflicts with established conservation paradigms that favor maintaining the status quo of species ranges, and in situ management strategies.

Although there have been vigorous debates among land managers and conservation biologists in recent years, it appears to be a subject insufficiently interrogated here at TNOC, especially amongst designers, artists, and urban ecologists. It’s time we applied this topic not only to exceedingly exotic plants and animals, but to our own species, and our primary habitat: cities.

What are the implications of considering AM of cities? To cities? Within and for cities? And what does it mean for the future of nature in cities?

Assisted migration of cities

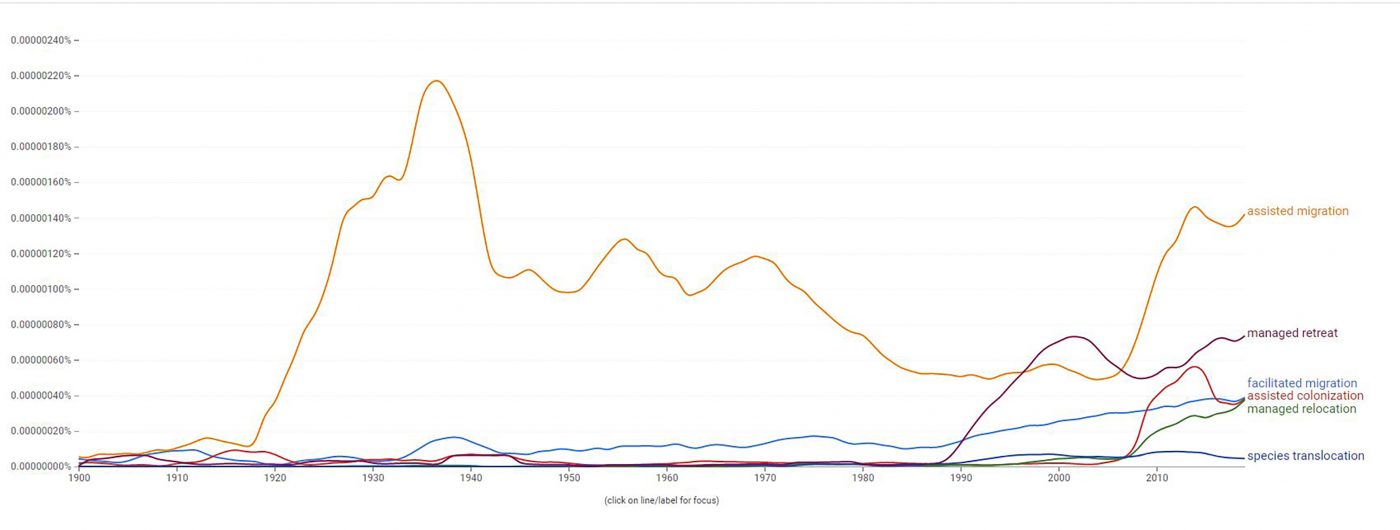

It is important to recognize that AM was largely a sociological notion before it was an ecological one. Before the 2000’s the use of AM in the English language refers primarily to the movement and displacement of human populations: across and within various regional and national borders and for various reasons not limited to climate risk aversion. It wasn’t until the late oughts and early 2010’s that interest (and debate) exploded among ecologists and conservationists (evidenced by analogous terms like facilitated migration, assisted colonization, species translocation).

AM of cities considers the possibilities for urban populations in risk prone areas, rather than investing in adaptation or mitigation (or continuously rebuilding in the same place), to pick up and move elsewhere. Starting in the 1960’s and 70’s, AM was used to describe efforts by federal and local actors to do just this.

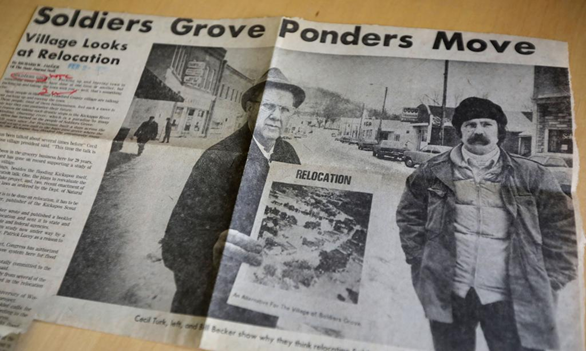

Consider, for example, the case of Soldiers Grove Wisconsin, a small logging town established along the banks of the Kickapoo river. After decades of devastating flood events and expensive subsequent rebuilding efforts, local authorities began to plead for federal funding—not to simply rebuild after flooding or invest in expensive levee projects along the Kickapoo, but to shift the entire city further from the river and onto higher ground. In the late 1970’s, they finally received authorization and federal funds to relocate large portions of the residential and business district to an area better suited for long-term resilience, with the lowlands of the former settlement converted to public open space.

Soldier’s Grove provides an example of what’s possible when local, state, and federal stakeholders work together on wicked challenges and think big. The question is whether the wholesale relocation of entire cities can or should be upscaled to other contexts in the face of climate change.

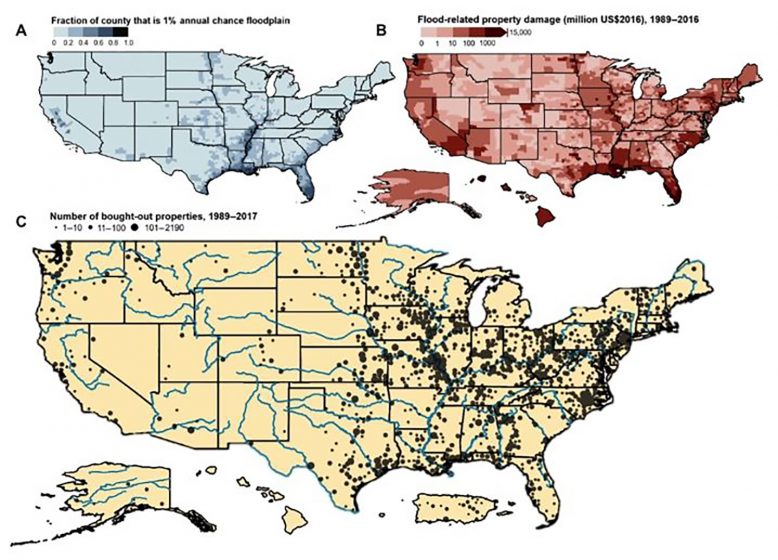

Today, this process is commonly referred to as “managed retreat” or “Climigration”, whereby entire communities are compelled (by legal and financial instruments) to move away from places threatened by floods, droughts, fires, and high temperatures. This usually entails a federally funded “buyout” of a homeowner’s property and assistance for relocation to a place of their choice. Unlike the case of Soldier’s Grove, a challenge often arises when some homeowners choose not to move or choose to move from one floodplain to another. There are many complex socio-economic factors at play, including questions of land dispossession through eminent domain, and the often-disproportionate impact these risks pose on already vulnerable communities.

To ensure such efforts are done equitably, with substantial subsidies to assist those who can’t afford it, managed retreat on a large scale entails enormous initial investment and the capacity for long term planning (not exactly the strong suits of contemporary American political system). Yet to date, the federal government in the US, primarily through the department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has already spent billions of dollars relocating at-risk populations (from floodplains, coastal areas, superfund sites, etc.).

But how might strategies for AM in the flood-prone parishes of coastal Louisiana look different from those targeting the high-end vacation homes in The Hamptons, on the coast outside of New York City? Notwithstanding the obvious logistical, geopolitical, and socioeconomic constraints, embracing AM of cities must contend with the reality that no place is really “safe” from the disruptions brought on by a rapidly changing climate.

The risks we face today extend beyond merely flood risk to include myriad challenges of drought, wildfires, agricultural failures, and civil unrest, among many others. The risks we face tomorrow will include those that we can’t currently anticipate, occurring in places we never thought they would.

Responding to these unpredictable patterns of disturbance may require that we collectively upend conventional models of home ownership and financial equity, which are currently based on long-term settlement in a single place. Resilience may soon entail frequent cycles of re-settlement in response to shifts in the geography of livability. In some ways the bourgeoning #Vanlife movement and the normalization of remote work and digital nomadism (for some) offer glimpses of the alternative models that may continue to set the stage for a more itinerant future. Will these trends remain reserved for the middle class with the skillsets and the means to move?

Or can we imagine it becoming a normalized reality for all?

If the assisted migration of entire cities seems far-fetched, it shouldn’t—especially if we pause to consider the estimated 250 million people globally living in areas that could be underwater by the end of the century.

Assisted Migration To (and Within) Cities

As with AM of cities, AM to and within cities is nothing new. For as long as humans have built and settled in particular places, we have been in the habit of moving things around and moving things in with us. We call it by a different name: Gardening. But gardening, perhaps, requires a more expansive definition as a process that includes not only conventional modes of planting selected species in our yards, but the various ways in which we curate plants, animals, and materials, and, in turn, how they cultivate us as humans. For thousands of years, we’ve harvested materials in some form or another from the larger landscape. Stone, mud, and timber are shaped into houses and temples and prisons. Even our sleekest modern buildings, rendered in steel and glass and gypsum are ultimately highly processed landscapes. In and around our built structures we cultivate our private and public landscapes in ways that reflect our norms and needs: For beauty, for shade, for food, for belonging.

We move species in and around with us in cities because they bring us joy. We own teacup yorkies and labradoodles that have been selectively bred to exhibit the traits we prefer. We plant begonias and lilies in our front yard to project an image of ourselves to the neighborhood. Many have known the pleasure of sneaking a clandestine cutting from a neighbor’s cactus and carrying it with the poise of an international spy, to plant one’s own garden (it’s a common theory in some urban gardening circles that stolen plants grow better). Gardening extends to commercial plant and animal trades, local seed banks and informal modes of seed exchange. Gardening includes the stowaway seeds we bring back with us on the soles of our shoes, embedded in the dried mud of a recent adventure abroad. Even our giving in to the allure of the latest houseplant (or pet spider) trend on social media often entails the mass movement of captives from some distant rainforest and into our bedroom.

Adding these exotic species to our urban landscapes often supplements, rather than supplants what was already there before. Invasiveness on the part of many common urban species is the exception rather than the rule. It’s by these means (and many others) that the vegetation observed in cities have grown to be, on average, more biodiverse than their surrounding hinterlands. This, of course, flies in the face of many tropes of city life as being somehow devoid of ecological complexity.

Cities are now home to a number of fascinating novel ecosystems (“freakologies”) that have arisen in tandem with our cities. From the thriving populations of escapee green parrots in the Telegraph Hill district of San Francisco to the Mexican Freetail Bats who’ve taken up residence underneath Austin’s Congress Bridge. These novel conditions are produced by (and generative of) many layers of social, ecological, and spatial complexity that were only beginning to understand.

Sometimes we go to extreme lengths, mobilizing considerable labor and resources to move species around. In 2014, private donors to the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business famously paid over 400 thousand USD to move a 250-year-old, 700,000-pound Burr Oak a single block to save it from the pressures of development. Salomé Jashi’s beautiful 2021 Documentary Taming the Garden depicts the movement of a single enormous tree across the Black Sea to a billionaire’s private garden in Georgia.

Whether by chance or by charter, we’ve proven ourselves capable of fundamentally altering the geography of other species. What if we embraced our capacity to cultivate novel urban ecosystems with more collective intention?

Assisted Migration For Cities

For better or for worse, the world we have inherited, the world we’ll leave to our children is an urban one. Recognizing the realities and disruptions of climate change means exploring new sets of intentions, new frames of mind, and new goals. Rather than fetishizing the protection or re-establishment (at all costs) of what thrived in a particular urban context in the past, we might instead invest our resources and attention on anticipating what might thrive there in the future.

AM for cities offers a hopeful conclusion to this triad and considers an alternative to the retreat of our own species away from cities. In an ironic twist on the very logic of AM, what if the intentional translocation of species in and to our cities help us to ultimately stay put?

AM for cities requires we look at species, not in terms of their geographic origins, but instead on their functional traits. Focusing on traits allows us to consider how and where those traits can be better leveraged in and around our cities and toward specific measures of socio-ecological resilience.

For example, in a hotter, drier future we might focus on drought-tolerant trees with big shady canopies which mitigate urban heat islands and maximize thermal comfort for the neighborhoods below. In an era of insect collapse, fast growing, perennial species with dense above-ground biomass might better support pollinators and viable habitats for other urban invertebrates. In an era of increasing urbanization, more intense storms and erratic stormwater runoff patterns, we must shape and plant our urban landscapes to better capture excess water and pollutants. In an era where human values will continue to matter a great deal, we must design planting and maintenance regimes that balance the need for urban beauty with the imperatives of ecological performance.

In some cases, finding appropriate species may require us to look far afield, and other times the answers may be right in front of us. As urbanization continues to shape the biotic and abiotic factors of terrestrial ecosystems, some common urban species that may be considered weeds today, may in fact become the keystone species of the future, providing a range of services that we don’t currently recognize.

Consider a recent example, beautifully documented by researchers Yuanquiu Feng and Yun Hye Hwang, detailing a dense Mangrove plantation intentionally introduced by informal occupants of a former landfill in the Baseco District in Manila, Philippines. Here, vulnerable urban communities recognized the need for an increased sense of community identity and ecological resilience along a riparian bank that was subject to frequent flooding during the seasonal monsoons.

Atop heaps of Styrofoam, plastic, and other discarded detritus, they cultivated the only space available to them, and it has grown over the course of just 10 years, into a thriving novel urban forest, offering provisioning functions to local residents and significant reduction in flood events. The success of these efforts has even sparked renewed interest in the revitalization of the larger Pasig River network (one of the world’s most polluted), with a number of other projects now underway.

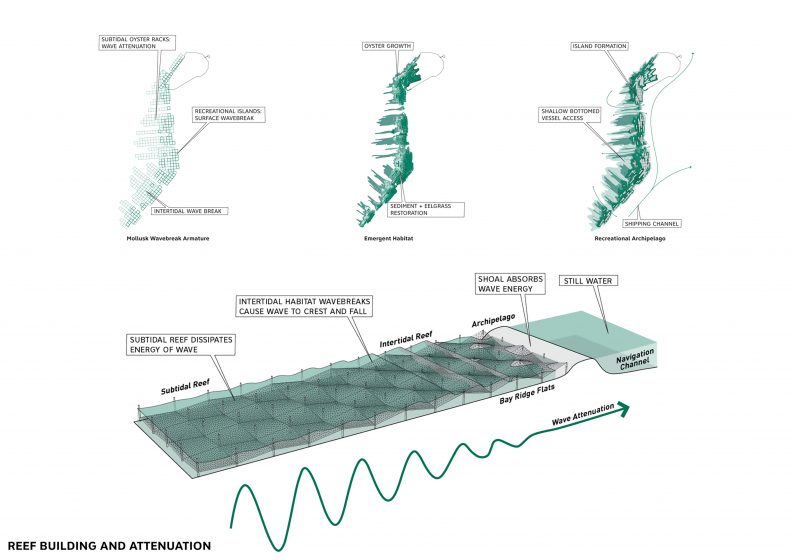

Other higher profile precedents are being developed by Landscape Architect Kate Orff/Scape Studio. Visionary waterfront proposals like Living Breakwaters and Oyster-tecture propose a network of coastal “scaffolding” that allows various aquatic species (including Oysters), to move in and thrive, while simultaneously providing water quality benefits, economic opportunities, and coastal armoring against future storm surges. The bold idea implied here is that we design and provide an armature upon which novel ecosystems emerge over time. We can invite rather than prescribe. We can catalyze new ecosystems rather than merely mourn the loss of historic ones.

Some may dismiss these approaches as overly optimistic hypotheticals. Yet, they are not as untested as they may initially appear. Researchers at Arizona State University recently reported that sunken ships provide the ideal habitat for reef-building corals, citing decades of case studies where accidentally or intentionally sunken vessels have been overtaken by thriving aquatic ecosystems. Could a larger-scale, more intentional version of these approaches (seeded with translocated coral species that can thrive in warmer waters) potentially offset the mass die-off of coral reefs elsewhere?

The Mesquite Mile, a project of which I am a co-collaborator along with Kim Karlsrud, Travis Neel, and Erin Charpentier, employs an AM approach for the purpose of urban afforestation. In this work, we focus on a single iconic species: the Honey Mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa).

The Mesquite has long been considered both a savior and a scourge for ranchers and farmers since the times of early Colonization across the southern High Plains region, providing needed shade and food for livestock during the hottest, driest stretches of summer, but quickly invading open grasslands and pastures when undigested seeds are deposited in the fertile droppings of cattle.

To contemporary farmers and ranchers in West Texas, the Mesquite is largely considered an invasive nuisance tree and is routinely removed through controlled burning, mechanical or chemical means in rural landscapes. Meanwhile, in nearby cities such as Lubbock, there exists an entirely different, and considerably more positive perception of this tree, its value, and its meaning. Urban properties in this semi-arid climate with any kind of tree come at a premium. It’s here in the city that the Mesquite, in particular, is widely known and celebrated for its lore, its delicate foliage, its pollinator-friendly yellow flowers, and its association with smoked meat.

It’s perhaps not surprising that urban trees are associated with increased property values, decreased heating and cooling bills, and higher urban biodiversity. But planting from a sapling can take decades to pay off (if at all). This high level of risk and lengthy time frame are more than many are willing to stomach. It’s this inverted perception of the Mesquite that drives our team toward a (provocatively simple) reciprocal bargain–to carefully facilitate the strategic relocation of these trees from one context to the other, and in so doing maximize their cumulative benefits over time.

Drawing upon over 4 decades of collective experience, we are exploring what is possible when Art, Design, and Science productively collide. Utilizing AM as a mode of public art and public placemaking, we are working with both urban and rural stakeholders to remove nuisance Mesquites from properties in the periphery of Lubbock county and replant them into volunteer front yards in the Heart of Lubbock neighborhood. To view footage of our pilot-scale assisted migration experiment, please follow this link.

These efforts, of course, are not without challenges. The success of any given transplant depends heavily on its size, the season in which it is transplanted (dormant defoliated is best), the underlying health of the tree, and the conditions of its new home. Another important factor is making these efforts palpable to the public by introducing conspicuous aesthetics of sustainability and supplementary programming alongside these interventions to encourage long-term care can be established. Public buy-in is an equally vital aspect of urban sustainability, without which even the best ecological intentions could fall flat. The long-term goal of these efforts is to invite communities to register these actions as contributive to a collective whole that extends beyond the purview of private landscape choices that currently dominate (and atomize) the identity of residential neighborhoods.

We are currently seeking additional funding to increase the scale of our Mesquite migration efforts and amplify the scope of our community engagement. This includes the creation of a public website for the project, a multi-lingual survey assessing public perceptions and needs, and the creation of a larger-scale network of demonstration sites in areas of the greatest need. We intend to track how translocated trees contribute to local biodiversity, hydrologic response, and thermal comfort over time.

Moving into an unsettled future

If the past 200 years of our urban story has been largely about mastering the patterns of settlement, the next 200 years will be marked instead by the patterns and processes of unsettlement. Although, not without controversy, Assisted Migration is one tool in a larger toolbox of strategies that can be aided by more transdisciplinary collaboration as we work toward building resilience in and around our cities. It presents unprecedented and exciting opportunities for Designers, Artists, planners, policymakers, and scientists to take action together. The issues and examples raised here barely scratch the surface. Consider this a call to continue and expand the conversation, here on TNOC, and within our disciplines. How is it that you consider the ethics, aesthetics, and ecological implications of Assisted Migration of, to and for cities?

Daniel Phillips

Lubbock

Leave a Reply