The city carries out a commitment to sustainable development under the motto “Respira Pinamar”, inviting residents and tourists to walk, ride a bike, and meet along a revitalized public space that allows perceiving nature and art through education and community awareness.

In Argentina, as a long weekend arrives many people living in the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires flee from the concrete and asphalt in search of Nature. There are many destination possibilities, but one that is undoubtedly a favorite is a garden city, 370 km south of Buenos Aires, which receives a million tourists in summer.

Its name Pinamar — pine + sea — describes the cultural landscape where sea and forest meet, following the vision of an urban architect 70 years ago. Jorge Bunge, Pinamar’s founder, brought the idea of a garden city from Germany, where he studied Urban Planning at the Polytechnic School of Munich. Upon his return to Argentina in 1939, he began to develop the idea of building a 2,700-hectare garden city.

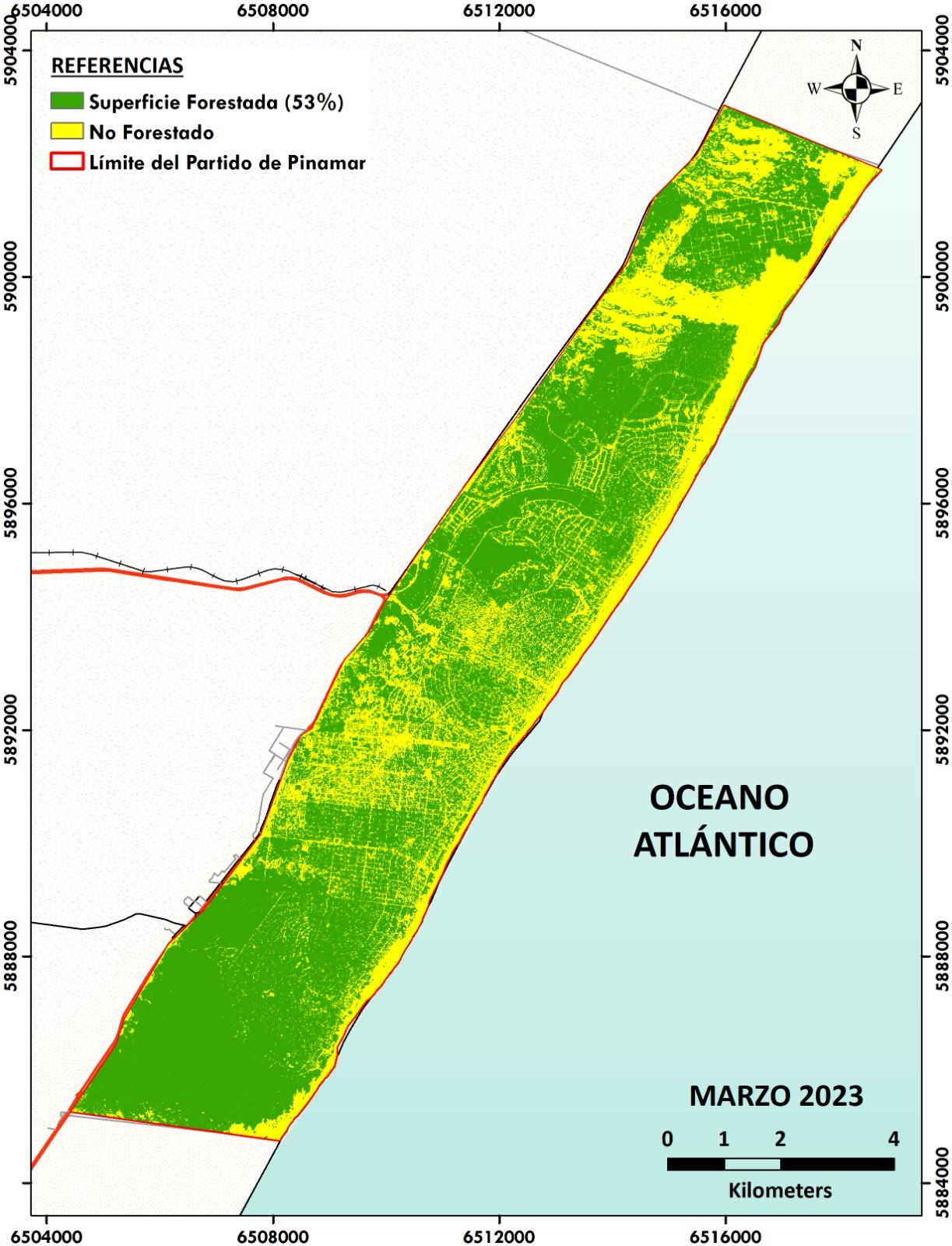

Thus, Pinamar had an origin that makes it almost unique in Argentina: it was conceived as a private initiative of a company that decided to develop its own land. This development was made with a particular urban vision: respecting the topography of the dunes but transforming the original natural landscape into a human-made one, creating a pine forest on grassy dunes (Fig. 1).

Its strong identity is linked to a way of building a city in the middle of pines, acacias, and eucalyptus forests that completely reject the colonial legacy imposed by the Spanish conquerors in Latin America: cities with very little vegetation arranged in a grid.

In Pinamar, the urban matrix expanded over large lots with garden retreats, curved streets, and tree-lined avenues (Fig. 2). A technical management of the urbanization was also used with a layout that follows the unevenness of the topography, the curves of the dunes, the rain runoff, and areas reserved for parks that include water channels.

There are very few examples of garden cities in Argentina: Palomar Hills in the Buenos Aires metropolitan area, also built in 1944 by German architects, City Bell in the vicinity of La Plata, and a few other garden neighborhood projects, linked to large industrial companies and designed for the residence of their officials and workers. Almost all of them finally remained as islands surrounded by a dense built-up matrix, under pressures imposed by the advance of growing urbanization. This is not what happened in Pinamar.

The city has kept environmental qualities, especially since it had gradual urban planning designed to achieve harmony with the landscape. Today, the spirit of the garden city is maintained, but not as a static sample based on the garden-city typology that Ebenezer Howard presented in 1898, which over the course of the century in different parts of the world was biased towards transforming neighborhoods for wealthy classes. However, it is necessary to remember that this was not Howard’s motor purpose. His aim was to reform society, claiming a new social organization through an urban and territorial model. Since he was not an architect by profession, he associated with two who were: Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker. Together they built the city of Letchworth, in England, as the first garden city which became an urban model of the 20th century.

Pinamar, a real estate development that was conceived as a vacation place, presents today a lively dynamic, carried out by a young municipal management group committed to sustainability. They keep the garden city identity, through a healthy balance between the origins and image of the city and the need to adapt this built landscape to the current environmental challenges. For this reason, the green is jealously maintained and today reaches 54% of its area with reforestation plans (Fig. 3). There is a forestry compensation strategy: for each pine or eucalyptus extracted, three specimens in 20-liter pots of native trees must be delivered to the municipal forestry bank.

In the planting of new specimens, an attempt is made to recreate a mixed forest where native trees, produced in the municipal nursery, are merged. These plantations provide boulevards and crossroads with greater biological diversity and improve aesthetics throughout the seasons with different textures, colors, and aromas.

The strategy means to discourage the planting of exotic pines, which although they gave the city its identity and name, do not achieve longevity and present a risk of falls by storms, which are frequent at the coast. They stopped planting Australian eucalyptus, for example, which are large trees that require a lot of water, a limited resource for a growing city.

Water for human consumption is a central theme and it is estimated monthly. Sidewalks are transformed into rain gardens to increase infiltration and prevent surface runoff and erosion (Fig. 4). These sustainable urban drainage systems are valuable water management tools. They generate considerable improvements in hydrological processes, strategically integrating runoff control elements into the urban landscape, with attractive aesthetics biotopes creating habitat and food for hummingbirds and insects such as bees and butterflies.

Another improvement strategy is the ecological dune restoration as well as the revitalization of the public space at the waterfront (Fig.5).

The city carries out a commitment to sustainable development under the motto “Respira Pinamar”, inviting residents and tourists to walk, ride a bike, and meet along a revitalized public space that allows perceiving nature and art through Education and Community Awareness. Urban sculptures, a 5 km linear park as an aerobic corridor, interpretive walks strategically designed to enhance the landscape while incorporating recreation, and leisure areas are valuable landmarks in town. This, perhaps an unintentional and ongoing commitment, honors Howard’s inspiring ideas and underpins the transformative social ideas of the garden city model that inspired him over a hundred years ago. The city goes beyond what was built, a thoughtful set of multiple elements that surprise the length and breadth of the city. Paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks (Fig.6), those elements that Kevin Lynch defined as building the image of a city are in Pinamar exceptional.

Paths |

Edges |

|

|

|

|

Landmarks

|

|

In a past contribution to TNOC in 2022, we mentioned that many families moved to Pinamar.

The city had a demographic growth of 17.5%. Building construction in Pinamar has grown 225%, eight times higher than the country average. Today, the city has 40,259 inhabitants spread over 3520 hectares. In other words, it has 7 times more space per inhabitant than Howard would have allocated for his garden city. This indicates that the growth potential is huge. This opportunity for development should be accompanied by smart and efficient governance so that the city does not lose the character of a garden city in the future.

We wish it to be so!

Ana Faggi and Maria Samanta Anguiano

Buenos Aires and Pinamar

On The Nature of Cities

about the writer

Maria Samanta Anguiano

She is a specialist in landscape design with an ecological perspective. Currently, she is the Secretary of Landscape and Environment in the Municipality of Pinamar.

Nodes

Nodes Districts

Districts

Leave a Reply