We have developed and applied new methods to evaluate how networks of plans address heat. We are building upon previous research suggesting that there are multiple complementary ways to evaluate plan networks. Here is the first step: the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ for Heat.

Cities everywhere are getting hotter due to climate change and the urban heat island. Places like the Pacific Northwest in the United States, which historically was not concerned about extreme heat as a climate risk, have experienced unprecedented heatwaves in recent years (White et al. 2023). These deadly events, as well as dire warnings for future heat increases from the latest IPCC reports, are a wake-up call for many cities, which are increasingly looking to actively plan for heat.

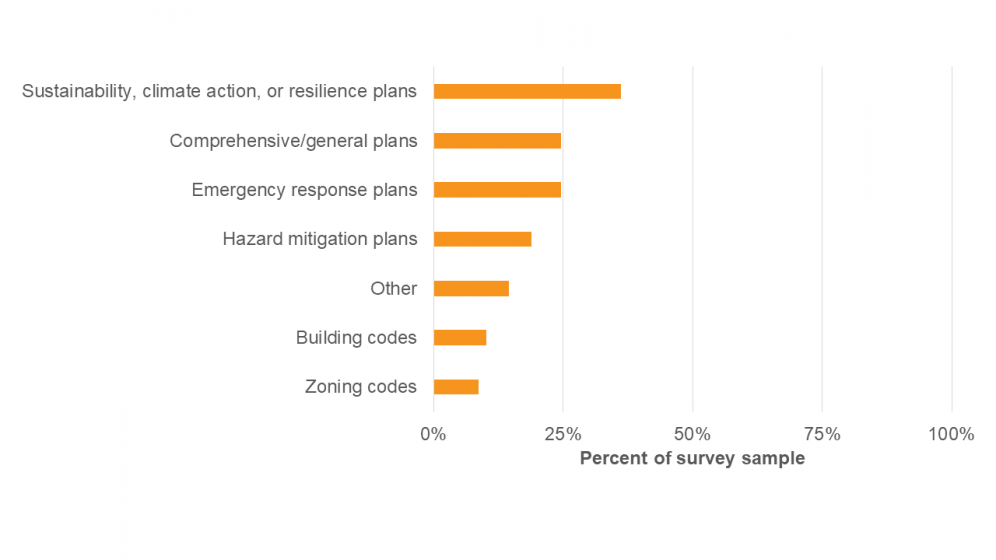

In 2021, we published the results of the first national survey of US planners focused on how their communities were planning for heat. Our survey confirmed that planners are quite concerned about heat and implementing different strategies to mitigate and manage its effects, but they also face many barriers. We also found that while most cities reported addressing heat in at least one plan, the type of plans where they incorporated heat varied (as shown in the graph below). Sustainability, climate change, or resilience plans, comprehensive plans, and hazard mitigation plans were all common choices, but none of them was mentioned by the majority of cities in the survey. This suggests that to effectively evaluate heat planning in a community, we can’t just focus on one plan, but instead need to understand the full network of plans that the community develops to guide future development and policy.

Networks of plans

We have written previously on this site about the importance of coordination across the network of plans for heat, drawing from our Planning for Urban Heat Resilience, published by the American Planning Association. Since then, we have developed and applied new methods to evaluate how networks of plans address heat. With this work, we are building upon previous research suggesting that there are multiple complementary ways to assess plan networks. Here we will outline our first approach, the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ for Heat, which adapts the original Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ methodology, initially developed for flooding, to the particular challenges of heat hazards.

The Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ for Heat

We developed the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ (PIRS™) for Heat as an extension of the original Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™, which was originally developed by Berke et al. (2015) and then further advanced and translated to planning practice by Malecha et al. (2019), for spatially evaluating networks of plans to reduce vulnerability to hazards. With support from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Program Office’s Extreme Heat Risk Initiative and in partnership with the American Planning Association, our research team piloted PIRS™ for Heat in five geographically diverse U.S. communities: Baltimore, MD, Boston, MA, Fort Lauderdale, FL, Seattle, WA, and Houston, TX.

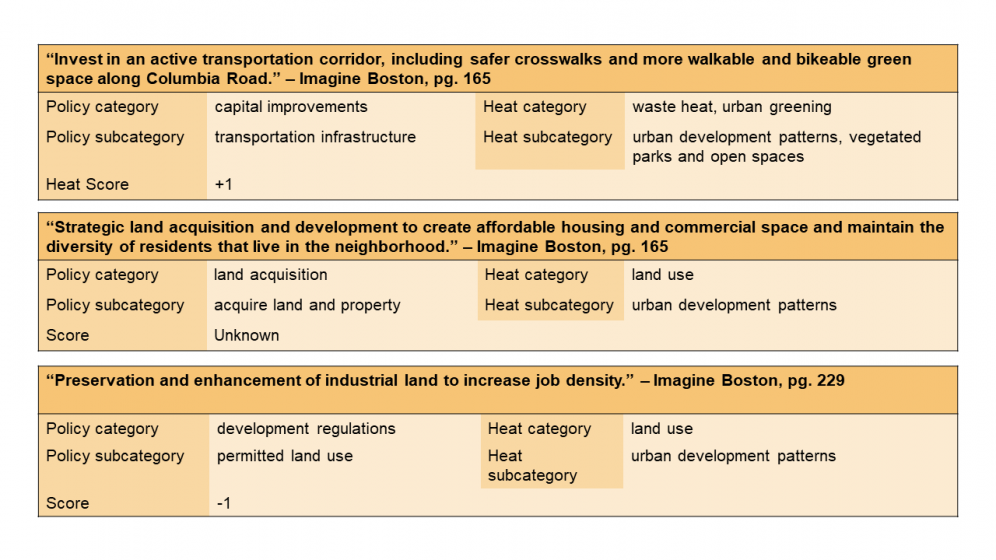

How does PIRS™ for Heat work? We read through a community’s network of plans, including their comprehensive plans, hazard mitigation plans, climate action plans, and climate change adaptation, resilience, or sustainability plans. We identify the land use policies or actions in those plans that pass the Three-Point Test (Malecha et al., 2019): (1) have the potential to impact urban heat, (2) are place-specific, and (3) contain a recognizable policy tool. We categorize those policies based on their policy tool and heat mitigation strategy and score them based on whether they would likely mitigate heat (“+1”), worsen heat (“-1”), or the impact is unclear from the description in the plan (“Unknown”).

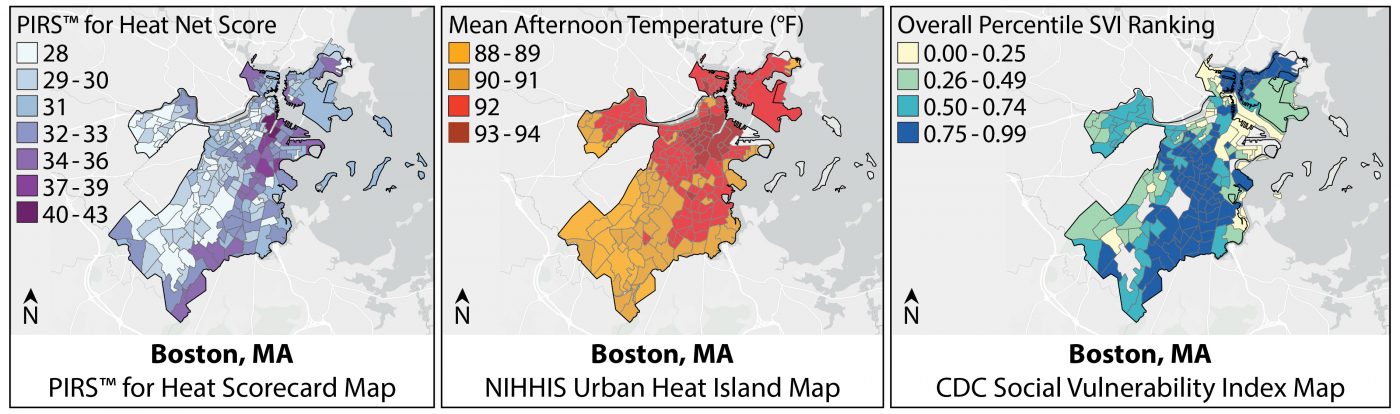

Scored policies are mapped to relevant census tracts across each community to evaluate their spatial distribution and the net effect on urban heat. The resulting PIRS™ for Heat scorecard is then compared with social vulnerability and heat hazard data to assess policy alignment with heat risks and to identify opportunities for improved urban heat resilience planning.

Below is an example of the resulting maps for Boston. More details on Boston’s results and the other four pilot cities can be found in the PIRS™ for Heat Guidebook. The map on the left shows the PIRS™ for Heat scorecard results, with darker tracts being those receiving more heat mitigation policy attention. The middle map shows mean afternoon temperatures based on the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) Urban Heat Island Mapping campaign, with darker tracts being hotter. And the map on the right shows the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index, with darker tracts being those deemed more socially vulnerable. Across Boston, we find that hotter and more socially vulnerable areas tend to receive more heat mitigation policy attention, which is what we would hope to see in more cities to address well-documented heat inequities.

An interactive web-based Storymap is also available for all cities we’ve completed.

Key lessons for heat planning from the five PIRS™ for Heat pilot cities

Our initial applications of PIRS™ for Heat provide several important lessons for heat resilience planning. First, we identify policies that would likely affect heat in all the plans we examined, further confirming the importance of evaluating networks of plans, rather than individual plans, to understand how a community is planning for heat resilience.

Second, while communities should aim for a diverse portfolio of heat mitigation strategies, some categories (e.g., urban greening and waste heat reduction) are more common than others (e.g., urban design). Similarly, communities rely more on certain policy tools than others (e.g., capital improvements, the land use analysis and permitting process, and development regulations).

We were encouraged to identify many policies across the plans that would likely mitigate heat, but often they were not explicitly linked to heat hazards. These are missed opportunities for communities to promote heat mitigation co-benefits and potentially increase support for those actions.

We also identified many policies with an “unknown” impact on heat mitigation, meaning they would likely affect heat, but they lacked sufficient detail in the policy language for us to determine whether it would increase or decrease urban heat. Communities should consider how new developments and investments are likely to affect urban heat.

With the exception of Boston, policies with the potential to mitigate heat were not consistently targeting the hottest and most socially vulnerable areas of pilot cities we examined. This suggests that more targeted heat planning is needed.

Finally, as we have shared these results with city officials in the pilot communities, it has become clear that the PIRS™ for Heat process can spark valuable conversations about heat planning and quality land use planning more broadly.

What’s next?

We are currently deploying PIRS™ for Heat to more cities across Arizona with diverse populations and climates as part of the new DOE-funded Southwest Urban Corridor Integrated Field Laboratory (SW-IFL). We plan to repeat the PIRS™ process in the future to document how planning for urban heat resilience has, hopefully, improved over time in certain communities and to evaluate how initial PIRS™ for Heat information was used in plan updates. This is important because longitudinal assessments of planning are few and far between.

We are also developing a new method of analyzing how networks of plans address heat and piloting it in several communities, the Plan Quality for Heat assessment. It complements PIRS™ for Heat because rather than just focusing on the land use policies with the potential to mitigate heat, it assesses whether plans include the full suite of heat mitigation and management strategies as well as other principles of quality planning, including the goals, fact base, implementation and monitoring, coordination, public participation, and uncertainty. These methods can help communities holistically evaluate their current heat resilience planning across their network of plans and more effectively prepare for a hotter future.

Sara Meerow and Ladd Keith

Tempe and Tucson

about the writer

Ladd Keith

Ladd Keith, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the School of Landscape Architecture and Planning at The University of Arizona. An urban planner by training, he has over a decade of experience planning for climate change with diverse stakeholders in cities across the U.S. His current research explores heat planning and governance with funding from the NOAA, CDC, and National Institutes for Transportation and Communities.

References

Berke, Philip, Newman, Galen, Lee, Jaekyung, Combs, Tabitha, Kolosna, Carl, & Salvesen, David. (2015). Evaluation of Networks of Plans and Vulnerability to Hazards and Climate Change: A Resilience Scorecard. Journal of the American Planning Association, 81(4), 287–302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2015.1093954

IPCC (2023). Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. A Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland (in press). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/

Keith, Ladd & Meerow, Sara. (2023). Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ (PIRS™) for Heat: Spatially evaluating networks of plans to mitigate heat Storymap. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/b01d63aee41c48b0804b77569f78cf21

Keith, Ladd & Meerow, Sara. (2022). PAS Report 600: Planning for urban heat resilience. Chicago: American Planning Association. www.planning.org/publications/report/9245695/

Keith, Ladd; Meerow, Sara, Berke, Philip, DeAngelis, Joseph, Jensen, Lauren, Trego, Shaylynn, Schmidt, Erika, Smith, Stephanie. (2022). Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard™ (PIRS™) for Heat: Spatially evaluating networks of plans to mitigate heat (Version 1.0). www.planning.org/knowledgebase/urbanheat/

Malecha, Matthew, Masterson, Jaimie Hicks, Yu, Siyu, & Berke, Philip. (2019). Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard Guidebook: Spatially evaluating networks of plans to reduce hazard vulnerability – Version 2.0. College Station, TX. https://planintegration.com/

Meerow, Sara & Keith, Ladd. (2022). “Planning for extreme heat: A national survey of U.S. planners.” Journal of the American Planning Association. 88(3): 319-344. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2021.1977682

Meerow, Sara & Woodruff, Sierra. (2019). Seven principles for strong climate change planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2019.1652108

Plumer, Brad & Popovich, Nadja. (2020). How Decades of Racist Housing Policy Left Neighborhoods Sweltering. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/08/24/climate/racism-redlining-cities-global-warming.html

Southwest Urban Corridor Integrated Field Laboratory. (2023). https://sw-ifl.asu.edu/

White, Rachel H., Anderson, Sam, Booth, James F., Braich, Ginni, Draeger, Christina, Fei, Cuiyi, … West, Greg. (2023). The unprecedented Pacific Northwest heatwave of June 2021. Nature Communications, 14(1).

Woodruff, Sierra, Meerow, Sara, Gilbertson, Philip, Hannibal, Bryce, Matos, Melina, Roy, Malini, … Berke, Phil. (2021). Is flood resilience planning improving? A longitudinal analysis of networks of plans in Boston and Fort Lauderdale. Climate Risk Management, 34, 100354. . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100354

Leave a Reply