The benefits of trees are irrefutable, but they are not widely understood and don’t seem to change behavior much. This suggests we need other approaches to convince people trees really matter. There are several promising directions.

Several weeks ago, I was startled when taking a typical morning walk to find that a large and majestic white oak tree had been cut down and lay in the front of a neighbor’s yard. It was a shocking and sad sight, a tree I had admired almost daily, reduced to a pile of sawed-up and lifeless segments on the ground. Several days later I happened upon the neighbor who was standing in front of his home. While I did not know him personally, I mustered up the courage to ask why he had cut down the tree. He hemmed and vacillated a bit in his answer and mumbled something about how the tree was leaning and felt it better to deal with the tree now than at some later point. He did not seem troubled at all about the decision, though slightly irritated at the question I posed. (Why is this any of your concern?) The tree looked to me to be quite healthy, and it was at least 15 feet away from the house. I remain perplexed by this decision, and the street and the neighborhood are poorer for it.

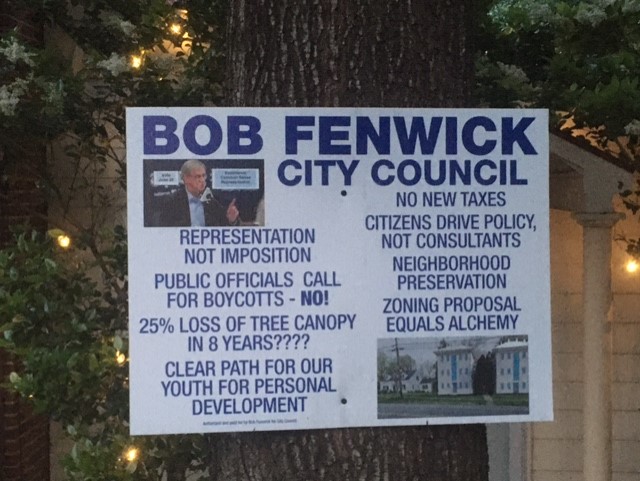

The last few months especially have been one similar sad discovery after another. It feels at times like I am living in a battleground (see the image below), with arboreal casualties piling up all around me. Many large trees are being cut down all around my city and the cumulative result is showing: a recent study found that the City of Charlottesville has witnessed a sharp reduction in tree canopy in a short period of time: from around 50 percent a decade ago to around 35 percent today.[1] We are still a leafy city, but the deforestation happening around us is clearly accelerating.

What is striking to me is the casualness of these acts. The loss of a several-hundred-year-old tree ought to be a gut-wrenching decision, made only as an absolute last resort. I am surprised that others don’t seem to care as much as I do or feel as emotionally and viscerally harmed by these decisions. Trees just don’t seem to matter much; I am perplexed about why that is so and what steps we might take individually and collectively to change this.

Image: Tim Beatley

I find myself often holding the thought that, unfortunately, while I find these older trees absolutely wondrous, many others in this otherwise environmentally aware and progressive community, do not feel the same way. And our city has an anemic tree code that does little to protect trees like this (though there are now proposals that would strengthen this code). The experience of discovering or in some cases watching a large older tree being cut down is not, unfortunately, uncommon.

My conclusion, unfortunately, is that trees don’t seem to matter much. They are viewed for the most part as largely inanimate objects. Even quite modest reasons seem sufficient to justify cutting down trees, despite the reality that the loss, especially of large-diameter older trees, represents a wound and harm that extends well beyond the crown or boughs or the root zone of the individual tree. The decision to cut down such a tree should matter dearly, and I am increasingly distressed by why this is not the case. And I desperately want to figure out how this could change and how we might grow or cultivate a society that appreciates the value of these trees, that believes deeply that they matter and that they should be, wherever possible, preserved, and cherished.

There are many explanations of course for why trees don’t seem to matter. Part of it could be attributed to what has been called “plant blindness”. That is, a tendency to care about animals and critters of all kinds that move and speak and grab our attention. There is especially a bias in favor of larger (and charismatic) mammals, of course, but even an ant or a mayfly receives more of our attention than the host plants that help sustain them. Paying full attention to plants and trees has always been a challenge.

No doubt that mattering challenges are made much more difficult by the prevailing ways we tend to see and treat the natural world. A big part of the problem is that trees are first and foremost understood as private property, to be used as a property owner sees fit, with little consideration of public impacts or implications. Many trees in cities are found in parks and public spaces, but often the majority of trees are found on private land. Boston’s recently released urban forest plan, for instance, notes that over 60 percent of its trees are found on privately owned land.[2]

What are we to do to create a world (and cities) where trees really do matter? One approach is to continue to talk about the many benefits trees provide, individually and collectively. To speak (as I often do) of the important shading benefits, of their value in capturing and retaining stormwater, and in sequestering carbon. I am often emphasizing the incredible beauty and delight that trees bring to me, daily and hourly. Trees and urban forests are having a day when it comes to appreciating their benefits in helping cities adapt to extreme heat. But perhaps we have forgotten all the other daily delights that trees provide and/or we tend to forget or minimize their value as an essential foundation in most of our daily nature diets. I think of the magnolia flowers that are starting to bloom here in Virginia, and the tulip trees flowering all around me. And, of course, each large tree is a remarkable and complex ecosystem itself providing spaces for birds, squirrels, and all manner of other life that animate our backyards and the spaces around cities. Without trees, there would be few birds, we know, yet we often fail to make the connection between tree conservation and the sights and sounds of the other nonhuman souls that we delight in seeing and experiencing. We would be lonely without trees and the remarkable habitats they provide. Perhaps there are more convincing arguments to make or perhaps they could be delivered in more effective or convincing ways?

And scholarly evidence mounts weekly, so perhaps an emphasis on these new insights would move the needle. This includes a recent study from Belgium that shows a sharp relationship between sales of mood disorder drugs and heart disease medication with the presence and size of trees―the larger the crown the lower the need for such medications.[3] Or the recent study showing the inverse relationship between trees and mortality.[4] The health benefits of trees, mental health benefits especially, are remarkable and to my way of thinking irrefutable.

These are all important arguments, and we should continue to make them. But they are not widely understood and unfortunately don’t seem to change behavior much. That is too bad, but it suggests we need other techniques and strategies and approaches if we are ever to reach a point where trees really do matter. What might be the antidote, or partial antidote to this problem? What might we do to shift our mindset and attitude so that trees do indeed matter? There are several promising directions.

Part of what we must do is better understand the psychology of trees and tree protection and factors that might influence a decision or more broadly the importance we give to urban trees and forests. Trees are cut down for various reasons, of course: a dislike for the leaves they deposit every fall, concerns about trees falling on roofs, a desire to let in more light, and often it seems a desire to change up the look or feel of a house. I do not wish to minimize these reasons, but they mostly seem insufficient to justify the loss of a grand and magnificent living being that does so much for us collectively. And I think we fail for the most part in our reasoning to think carefully and adequately account for the public costs on the other side of the ledger sheet. In working on behalf of trees (making trees matter) should our approach be to counter each of these arguments? For example, it is ok, indeed ecologically preferable, to let the leaves fall where they will.

Trees for most of us largely recede into the background of our lives. We may not be alarmed by their loss, when it happens, in part because we tend not even to notice or pay much attention to them. As the late poet Mary Oliver has pointedly observed, “attention is the beginning of devotion”. How do we work to make the trees around us more visible and important? What can we do to help to make them matter?

Making trees personal

Dating trees might help persuade some of us about their right to exist. When I speak of the estimated age of the grand white oak that sits adjacent to the UVA School of Architecture―likely close to 300 years old—it never fails to generate an audible “wow”. If we had to attempt to raise an oak tree from an acorn (something I have been trying to do) we would further appreciate just how unlikely and difficult it is that trees of this age and size exist around us.

We must truly see and experience the trees and forests around us, in personal and visceral ways, for them to matter. These can happen in many creative ways. In many places, there are organized tree walks and community tree celebrations. In some cities, there are annual “Tree of the Year” competitions. There are online maps that help us collect and disseminate the personal stories and histories of the trees around us. QR codes, Virtual Reality, and many other digital technologies are increasingly used to foster greater awareness and connection. I am reminded of the primary school in Western Australia I had the chance to visit years ago where all students learned to identify native species of trees and where a native “bushland” behind the school became an important space for learning about and connecting with nature. Or more recently the schools in Berkeley, California, that are engaging students in the planting of schoolyard mini-forests, using the Miyawaki planting method.

There are also so many ways that we can practice modern life (and lives) in ways that pay attention to the trees around us; that actively acknowledge them as co-occupants and co-citizens. Standing up and actively giving voice to trees is one way, and we have many good examples of where that has been and is happening. Mourning and grieving the loss of special trees (several years ago a colleague of mine wrote and distributed an obituary of one special tree). Recognizing the many ways that the histories and lives of trees and humans are bound together (and collecting those stories, for instance through an online initiative started at Portland State called Canopy Story[5]). Various tree rituals are helpful as well, some even daily. For example, I hold “tree hours” for students in my classes, convening under an old white oak.

Starting tree rituals of various kinds is another possibility.

Here at UVA, I now require students in my Cities + Nature class to keep a nature journal and one of the directed entry assignments is to find and write about their favorite tree on campus. Part of that involves learning as much as they can about that tree and drawing it. Many students are not very confident about their drawing skills but often produce remarkably detailed pictures of their favorite trees, evidencing considerable time noticing the details and observing firsthand the life of this tree. Spending time noticing the trees around, learning their common species names, the colors, and shapes of leaves, and sitting under or near them to listen to the sounds that emanate—what writer David George Haskell has called the “song of trees”[6]. Calculating the age of a tree is another way to particularize it―and also to gain a sense of perspective about what it took to live and grow and survive over a long period of time. The more we learn and absorb about a particular tree the more we are likely to care about it and come to its defense.

The more we know about specific trees, the less likely we are to see the decision to cut down a tree as a trivial thing. The more it is understood to impact a family member, the more that tree will matter, and the more protective we are likely to be.

A tree as a who, not an it

Naming trees will also help. While subject to the perennial criticism of over-anthropomorphizing, where we can we need to name trees. Specific names that send the signal that a specific individual tree, standing before us. It is a fungible entity―that can be traded off in some way, but a living individual deserving of attention and care. There are recent examples of how effective such an approach can (sometimes) be. In Seattle, for instance, a large western red cedar known as “May” was in jeopardy of being cut down when neighbors joined together to lobby for its protection.[7] Almost everyone in the Seward Park neighborhood seemed to know May, and eventually, the residents were able to convince the owners, who were building a replacement home to one that had burned down, to save the tree. As in so many cases, it is not clear why the owners would have needed to cut the tree down in the first place.

Native American author Robin Wall Kimmerer, in her powerful book Braiding Sweetgrass, rightly concurs about the importance of names and naming in the Seattle example.[8] Naming means they become people. Native Americans speak of trees and forests, she tells us, as the “standing people”, and view nonhuman lives through a lens of kinship. How we speak about the trees around us conveys much of what we believe about them.

A “grammar of animacy”, she advises, strengthens this sense of trees as people. Conversely “when we tell them the tree is not a who, but an it, we make that maple an object; we put a barrier between us, absolving ourselves of moral responsibility and opening the door to exploitation”.[9] I make a point, where I can catch myself, of never calling a tree an “it”, or a bird or an ant, choosing a gendered pronoun. It is not perfect, but such practices will help to see the trees around us in a different way.

Kimmerer eloquently describes the central role of gratitude and reciprocity in indigenous cultures. Gratitude begets reciprocity; expressing gratitude for the gifts given to us by trees around us (in cities especially) is a good start: the gifts of shade, water, food, birds, and beautiful colors, among others. “One of our responsibilities as human people is to find ways to enter into reciprocity with the more-than-human world”, Kimmerer says.[10] What would reciprocity look like for urban trees? Taking meaningful steps to care for and water trees in times of drought, to steward over and protect them from the incessant chainsaw.

A new tree ethic

As much as anything, then, we need to develop and disseminate a new ethic of trees; one that sets out a new narrative about them, and new assumptions about their relationship to humans. It would necessarily build on these Native American notions of trees as kin and the importance of reciprocity. Another element of this ethic involves the inherently public nature of the decisions made about them, especially older, ancient trees. As trees get larger and older the magnitude of their impacts all grow: the extent of the shade they provide, the caterpillars they offer up to nesting birds, and the carbon they sequester. In this way, their “publicness” grows substantially over time. The loss of such trees will have a large public impact. Protecting and caring for these trees can be framed as a civic act and as a modern element of what it means to be a good citizen.

Margaret Renkl, writing in the New York Times, calls for a “profound paradigm shift”. She says so eloquently “We need to stop thinking of trees as objects that belong to us and come to understand them as long-lived ecosystems temporarily under our protection. We have borrowed them from the past, and we owe them to the future”.[11] She rightly points out the temporary tenure we hold over these old trees and our duty to ensure that they exist in the future.

What Renkl is describing really is the need for a new kind of tree ethic; a collective sense of what we owe trees and forests, and what our ethical obligations are to them and relative to them. We are duty-bound, I believe, to recognize the immense public benefits they provide and to treat them with care and respect. Older, larger trees especially ought to be understood as living elements of our communities worthy of celebration, veneration, and protection.

This brings us closer to the idea of the rights of nature, a perspective growing in importance globally. The view that that tree or that urban grove has intrinsic moral value and an inherent right to exist, irrespective of whatever utility or value the tree has for humans. It was a profound, and still quite a new idea, when I first read Christopher Stone’s groundbreaking essay “Should Trees Have Standing”.[12] He proposed then, in 1972, the “unthinkable”: “that we give legal rights to forests, oceans, rivers and other so-called ‘natural objects’ in the environment―indeed to the natural environment as a whole”.[13] It is a natural extension of naming those trees if they are understood to be living individuals. And the work of tree luminaries and pioneers like Suzanne Simard, and Diana Beresford-Kroeger, have helped us to see how complex and wondrous trees and forests are; and to begin to see them as living creatures with agency and sentience.

Most of the official signals we send about the older trees around reinforce the sense that these trees are of nominal value and akin to landscaping choices made by a homeowner. That could change. The adoption of a strong tree protection ordinance or code would help greatly, though lax enforcement often reinforces the sense that decisions about trees are best left to the property owner.

Acknowledging the great trees among us

Paying homage to the grand trees around us would also be a good step in the right direction. On a recent trip to Atlanta, Georgia I sought out (to visit and see) the oldest tree in that city. I found it, thanks to an online list of Champion Trees kept by the nonprofit Trees Atlanta. It was a Cherrybark oak, a remarkable 274 inches in circumference. Her crown was immense, shading much of the opposite side of the street. I doubt many residents of Atlanta know her, nevertheless, make time to find and visit her. But they should. And we should, in the cities and neighborhoods where we cohabit space.

Image: Tim Beatley

I also feel that many decisions about the status of larger trees would benefit from conversation and discussion among neighbors. This again flies in the face of the “a tree is private property” belief, but I think it is undeniable that outcomes would be different if the owner of an older tree fully appreciated the extent to which that tree or drive was valued and enjoyed by others in the community.

And here the power of peer pressure might help to strengthen a collective tree ethic. Aldo Leopold in his famous book A Sand County Almanac contemplated what it would take to implement a land ethic. He rightly notes that the most effective ethic is one that is enforced through public sentiment and community attitudes: “The mechanism of operation [of the land ethic] is the same for any ethic: social approbation for right actions; social disapproval for wrong actions”.[14]

Here I am reminded of the late poet Mary Oliver’s remarkable poem “The Black Walnut Tree”.[15] In it, she and mother (I am assuming she is relating a personal story) grapple with the economic decision of cutting down a beloved Black Walnut tree, concluding in the end not to cut it down. In the poem, Oliver and her mother talk it through, “two women trying in a difficult time to be wise”. Careful and thoughtful deliberation is needed but so often lacking when it comes to decisions about trees. In the end, “Something brighter than money moves in our blood,” says Oliver, and the decision is made to save the tree.

Is this “something brighter” a love for the tree, or perhaps a sense of stewardship, a recognition of personal responsibility to care for the tree and the many animals and other living things that rely upon it as their home? Is it a sense of civic duty to refrain from destroying something that is such an important collective good? It is not clear in the poem, but there are hints of these considerations.

Selling the tree might pay off the mortgage, writes Oliver, but if they did this, “what my mother and I both know is that we’d crawl with shame in the emptiness we’d made in our own and our fathers’ backyard”. The poem reflects the sense of collective or familial disapproval and hints at the importance of this in understanding the psychology of these kinds of decisions. In contrast to this poetic story, there is rarely the feeling of shame. It is more akin to changing a sweater or choosing a different color paint for the exterior of one’s house. And at a time when we are even less likely to know our neighborhood perhaps it is unrealistic to expect much of such a strategy or to assume that a homeowner will care at all what others might think of her actions.

Those of us lucky enough to have older trees ought to think about the legacy value of taking steps to protect them and passing them along. Many of us who are moving into our elder years ought to be experiencing what social psychologist Erick Erickson described as “generativity,” the desire to think about one’s legacy, what one will leave behind, a natural desire that tends to emerge in the last stage of human development. As the number of people 65 and over rises sharply perhaps there will be a rapid rise in legacy thinking and actions that tree protection can rightly tap into? One of the largest and oldest trees here in central Virginia is a white oak, now adjacent to our airport, that was preserved in the will of the landowner. Giving new meaning to the idea of a living will, I’d like to challenge older folks to think about how they will protect and pass along the giant trees around them—putting in place legal protections that will ensure the acts of passing along that Renkl speaks of above.

Economic signals

There are other things we can do, of course, including working to change the economic and moral signals we send about the trees around us. I have advocated for many years the need to reform our local property tax systems to better take into account trees and the ecosystem services provided especially older, larger trees. Most local property assessments do not explicitly consider trees, but they could. A homeowner willing to protect a large older tree, or several, is entitled to a rebate or reduction in their tax bill that reflects the ecosystem benefits provided by the tree or trees. If the tree is cut down, the annual financial benefit goes away and so there is a tangible cost borne by the property owner.

There are many precedents for such an approach to point to. In other parts of the world, the idea of offering annual payments for actions that support the protection of the environment. In the Netherlands, farmers have received payments for protecting endangered species. In the US, we have precedents as well. Many cities now have stormwater management districts that assess a stormwater fee calculated according to the extent of impervious surface and the presence of trees and vegetation. Cities like Los Angeles and Las Vegas have generous financial rebates for homeowners willing to take out water-thirsty lawns and replace them with xeriscaping and drought-tolerant plants. And I recently wrote about a community in Florida that has been providing a subsidy (small to be sure) for homeowners willing to host nests of burrowing owls.[16] There are lots of examples of the kind of economic incentives that would make a meaningful difference. And in addition to the economic calculus offered, they also have the benefit of sending a clear message to property owners (and the larger public) that trees do indeed matter.

The public trust doctrine

We also need to address some of the false arguments that defend or support the casual and callous cutting of older trees. One I hear often is that a tree is coming to the end of its life anyway so why not cut it down? New research suggests that trees (unlike humans) don’t die of old age but rather from some specific threat or ailment―they are hit by lightning or succumb to a disease or a pest. Most of the large trees I see could easily live for many more years, and don’t exhibit signs of disease or distress.

Still, there is the retort that trees are private property, and their disposition is rightly the domain of private decisions by those who own them. But private property rights are always subject to the constraints of the larger public good. There are many legitimate limitations placed on the exercise of private decisions and private freedoms to support a larger public interest.

Could the public trust doctrine apply in such cases?

The public trust doctrine is a common law principle drawn from our British legal heritage and earlier still from Roman law. It is the doctrine that establishes our right (the public’s right) to access and move along navigable rivers. And in every coastal state, it ensures that the public has access to and is able to walk along the wet beach (and in several states, this right applies to the dry beach as well, at least up to the first line of vegetation). It has been used as the basis for protecting coastal wetlands and even more recently, it has been argued, for the protection of our collective atmosphere on which all human and nonhuman life depend.

Given that larger older trees in a city provide such undeniable public benefits, individually and cumulatively, the public trust doctrine would seem a highly relevant tool to defend and underpin limits on the right of a property owner to cut down such trees. As with beaches, wetlands, and rivers, trees and forests would seem similarly imbued with intrinsic qualities of publicness. I do not know whether state or federal courts would sustain an application of the public trust doctrine to the protection of local trees, but this seems a logical and defensible application, at least to me.

There are always constraints on the exercise of individual rights, and it does not seem unreasonable to place restrictions on the ability to cut down such a tree given the public implications. But there may be times, of course, when, in our effort to protect trees, may leave a property owner with few other economic options. Some cities are now using TDR (transfer of development rights), to allow a landowner or developer to transfer unused density in cases where, to protect a tree or tree grove, he/she is not able to achieve the maximum permissible development. And it is not unreasonable to ask that building and development plans and designs be adjusted (e.g., so that homes are more vertical, building footprints are shifted to avoid existing trees). Some city tree codes require that developers go through a process of avoidance where protected trees exist on site.

And sometimes a city may need to be ready, albeit in rare cases, to purchase a site with a tree or grove of trees when the regulatory impacts on a landowner are too great. There is a recent example in Toronto of a 250-year-old red oak under threat, perhaps the oldest tree remaining in the city. The city ended up buying the tree (and the house and lot it occupied) for $780,000 (Canadian dollars, or around $570,000 USD, about half the funds were raised from private donations, it should be noted). This may seem a large sum to expand for a single tree, but it does suggest the need to explore options for publicly purchasing trees in some situations (where preserving the tree leaves a property owner no or highly curtailed development options). Perhaps we should explore the possibility of adapting more traditional (conventional?) land conservation tools to urban settings: purchasing tree conservation easements, for example, or seeking donations of tree conservation easements, that would essentially create a protective provision (running with the property deed) for a specific tree or grove.[17]

Tree conservation tools

Part of the answer is to apply new tree conservation tools that help solve this program or adapt existing tools. Portland, Oregon (and maybe other cities) has adopted a tree TDR provision that allows a landowner to transfer (or sell) unused development potential―that is, if because of the need to protect an existing tree or grove, it is not possible to reach the full permitted density. This would work in concert with the kinds of financial annual subsidies mentioned earlier. Undoubtedly there are other planning tools that communities could use that I have not heard of or thought of. Lack of tools should be an excuse for the loss of trees and canopy.

Image: Tim Beatley

Standing up for trees

Can this new tree ethic, or paradigm shift to use Renkl’s terms, really transcend politics, and should it? Rather than transcend it, it must underpin and guide local politics. While I have pointed out the importance of individual behavior when it comes to the trees around us, at the end of the day the political system must deliver the strong tree codes we want and need. We should still have heated and earnest conversations about the trees in our neighborhood, and we should engage our neighbors in discussions about the trees they share on their street, certainly, but we should also demand that trees throughout the community be protected, even those lacking the visibility or the support of a nearby engaged neighbor or group of neighbors.

Standing up for the trees around us has the potential to significantly change local politics. I have been encouraged that, in my home city, the loss of trees has found its way into a recent local political campaign (see/note the recent campaign sign above). This is a good start [though the local press needs to do a better job reporting accurately on tree loss: one recent local newspaper headline reported the canopy decline as 15 percent when really the loss is closer to 30 percent]. And the city has begun work on a new tree code, though it remains to be seen how stringent it will be, and how assiduously it will be enforced. Cultivating a deeper community tree ethic will remain an important and necessary step and is the best assurance that politicians and neighbors alike will begin to see how and why these majestic trees “matter” and work hard to protect them.

Trees do matter and those of us (most of us) who believe strongly that they do must stand up and say so. We must name our trees, celebrate them, and speak their praises, and work for stronger codes and ordinances that acknowledge both the immense beauty and health they bring us, but also their inherent value and right to exist.

Tim Beatley

Charlottesville

1 Charlotte Rene Woods, “Charlottesville’s tree cover has dropped about 15% since 2004–but there are ways to bring it back,” Charlottesville Tomorrow, April 5, 2022.

2 City of Boston, Urban Forest Plan, September 21, 2022, p.47, found here: https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/2023/03/2022%20Urban%20Forest%20Plan%20-%20two%20pages-3.pdf.

3Dengkai Chi et al, “Residential Exposure to Urban Trees and Medication Sales for Mood Disorders and Cardiovascular Disease in Brussels, Belgium: An Ecological Study,” Environmental Health Perspectives, Vol 130 No 5, May 11, 2022

4Geoffrey H. Donovan, et al, “The association between tree planting and mortality: A natural experiment and cost-benefit analysis,” Environment International, Volume 170, December 2022

5See “Canopy Story” found here: https://www.pdx.edu/sustainability/canopy-story

6David George Haskell, The Song of Trees: Stories From Nature’s Great Connectors, Viking, 2017.

7Agueda Pacheco Flores, “Seward Park Neighbors Come Together to Save an ‘Exceptional’ Tree,” South Seattle Emerald, March 10, 2022, found here: https://southseattleemerald.com/2022/03/10/seward-park-neighbors-come-together-to-save-an-exceptional-tree/

8Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants, Penguin Books, 2013.

11Margaret Renkl, “How Do You Mourn a 250-Year-Old Giant?” New York Times, January 24, 2022.

12Christopher Stone, 1974. Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects, Los Altos, CA: William Kaufman.

14Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac, New York: Ballantine Books, 1949, p.263.

15Mary Oliver, “The Black Walnut Tree,” in New and Selected Poems, Volume One, Boston: Beacon Press, 1992.

16See Beatley, “The Burrowing Owls of Marco Island,” Biophilic Cities Journal, May 2022, found here: https://www.biophiliccities.org/bcj-vol-4-no-2

17This is sometimes referred to as Purchase of Development Rights (PDR), and has been used extensively to protect farmland and ecological lands such as wetlands.

Leave a Reply