At a time when abundance seems to be getting all the attention, we must acknowledge, at least when it comes to water, the reality is scarcity.

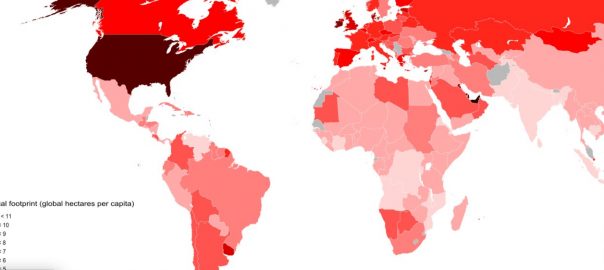

After living part of a sabbatical semester in Santa Fe, New Mexico, I have come to more fully appreciate the value of water. Growing up on the East Coast of the US, we tend to take for granted the presence and ubiquitous nature of water. Where it is scarce, such as in the American Southwest, it seems even more precious and beautiful, and in these moments of water awareness, there are lessons for many other arid and not-so-arid cities and regions in the world.

In New Mexico, I was re-acquainted with some of the unusual institutions that have evolved to manage this sacred water. Only a block or two from our home was the Acequia Madre (Mother Ditch), an ancient water irrigation ditch that has been transporting and spreading water from the Sangre de Cristo Mountains for centuries. It is part of a larger tradition of collectively and democratically managing limited water supplies that dates back hundreds of years.

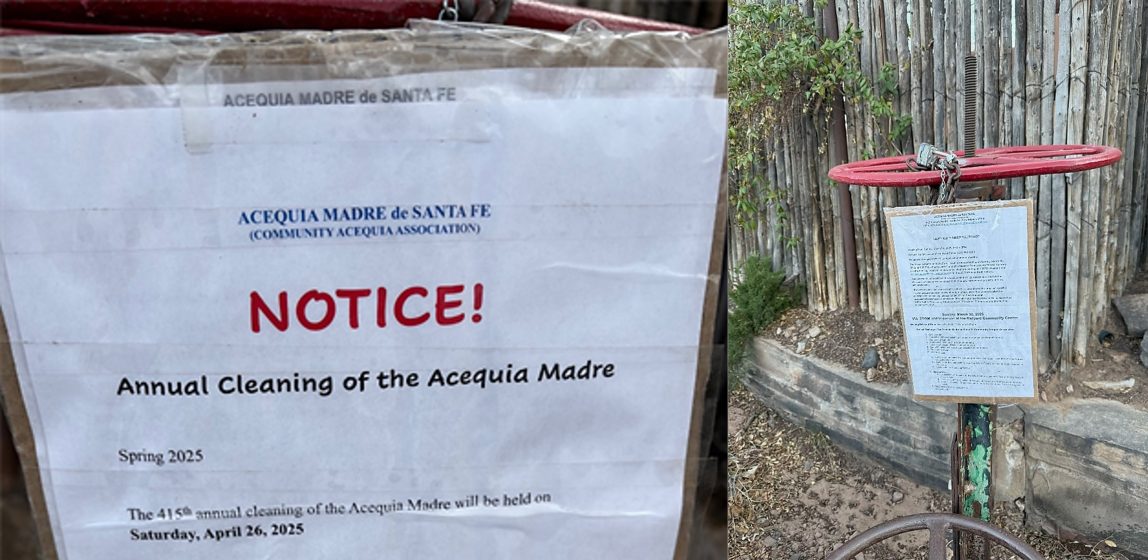

Acequias, from the Arabic “as -saquiya,” meaning “that which brings water”, are collectively governed water ditches or irrigation canals. It is a tradition brought by the Spanish to the New World that was built upon and was inspired by indigenous water management that has existed for even longer. The hand-dug, gravity-fed earthen ditch that we got to know well is, remarkably, more than four hundred years old. This democratic institution is very much alive and well in New Mexico, where there are an estimated 700 functioning acequias around the state (and another 70 in southern Colorado). As visitors, we were warmly welcomed into the acequia world, attending the Acequia Madre annual meeting and participating in the annual community cleanup and maintenance.

For much of the year, acequias are dry. Visitors often see them and think (not unreasonably) that they are drainage or stormwater collection channels. There is something quite unusual about their fast flow and the magical way they hug the edges of walls and bend and snake their way through a neighborhood, with many creative bridges and connections to front doors and side yard entrances. These are what some have called elements of “cultural greenery”, and like the immense cottonwoods that dot this city, are a steady and reassuring connection between past and future.[1] We knew the story of these ancient irrigation ditches, but were still surprised by the notices along the Acequia Madre announcing the “415th annual cleaning”. Few traditions last this long.

One Saturday morning in March, with rakes in hand and some basic instructions (clear out anything larger than your fist!), we set out to clean up a section of the seven-mile-long acequia. It was less than entirely obvious what we needed to do in the dry bed (much of the debris and trash had already been cleared earlier by city of Santa Fe workers, a helpful commitment by the city to maintain the remaining ditches), but it was a chance to work with others in ensuring the long-term health and survival of this unique waterway.

Waiting for the water may be part of what makes it so deeply enjoyable when it finally comes. The Acequia Madre water runs every Monday, starting in May and lasts into the summer―months that are especially important to grow food and to sustain birds and their young clutches. Like the snowmelt in this part of the country, the acequias help to strengthen a sense of the seasonality of this arid place.

Acequias represent one of our oldest forms of democratic governance, older by more than a century than our Declaration of Independence. The governance structure includes an elected mayordomo (essentially the chief “ditch officer”) as well as elected commissioners. Our brief film below includes an interview with Acequia Madre’s current mayordomo, Eric Montoya, and one of the acequia’s most active commissioners, Miche Bové Garcia. Along with some accompanying footage, it provides a window into what this ancient institution means to Santa Fe and other communities around the state.

It is a refreshing story at a time when so much of our collective lives are lived online and without direct connections to place and nature. In acequia culture, it is people, with their knowledge of their communities and environment, who devote their time and physical labor to the care and protection of this life-sustaining cultural asset.

There are challenges, of course, in maintaining this democratic tradition, as our short film suggests. Acequias have been disappearing in many cities and in the more urbanized areas, especially. In Santa Fe, there remain just four acequias where there were once forty. Yet, they still provide a model of resource democracy, for how to manage collectively an essential resource–water–that every person and living creature needs and relies on. Admirers of the ancient method of water management rightly lament the prevailing system of water rights, which has mostly replaced the sense of water as a precious collective resource with the notion of water as an economic commodity to be bought and sold.

The value of a network of citizen-managed acequias is undeniable. They have an essential role in distributing scarce water to farms and villages, and an important role in recharging groundwater, as well as providing key habitat for birds and other biodiversity, as a 2021 article in Audubon Magazine makes clear. Quoting Enrique Lamadrid, a retired University of New Mexico professor and expert on acequias: “We forget to give acequias credit, but acequias broaden and expand the riparian zone…Where there are acequias, there are beautiful trees full of birds.”[2] One of the other remaining acequias in Santa Fe, Acequia del Llano, runs through and helps to nourish the Randall Davey Audubon Sanctuary, a remarkable birding site and habitat, where we often delighted in seeing several species of hummingbirds.

There is special value in creating mechanisms where we are expected to commit our time and energy to manage resources together, especially water, that we all rely upon but rarely have a hand in protecting. It is partly about cultivating a citizenry that better understands the hydrological context and setting, and by doing so, will be more likely to adjust its use and resource-impacting behavior. It accentuates the crucial sense that these are resources we all depend upon, and it builds important place-knowledge. More importantly, it has the potential to instill in participants a deeper sense of place and a deeper connection to the nature around them.

There are many other arid or semi-arid places where acequia traditions and cultures have taken hold, sometimes even in larger cities. Andrew Bernard, Landscape Architect and adjunct at the University of New Mexico, has been documenting the “tree-acequia” tradition in Mendoza, Argentina, for instance, where a network of acequias sustains the city’s urban trees. Bernard describes how Mendoza’s acequias “sustain a robust urban tree canopy and plentiful green spaces,”[3] not only sustaining the city’s trees but also allowing these life-sustaining water channels to become a visible part of the city, “not hidden away underground.”

In unexpected ways, the scarcity of water heightens the experience of it. The modest Santa Fe River, in comparison even to the small creek near our Virginia home, becomes the focal point for much respite, strolling, and socializing, especially along the city’s beautiful riverfront park. There are few spaces more beautiful or soothing.

In a modern world in which few understand the ecology (or hydrology) of the places they reside in, few know meaningful things they could engage with and protect these life-sustaining ecological processes and assets. And as a result, the fundamental preciousness of water may be lost on most of us.

Perhaps public art could help to activate some of this eco-awareness. As the Acequia Madre was getting organized to welcome back the summer water, renowned eco-artist Stacy Levy arrived to lead a collective process of painting and making visible some of the now missing acequias. Levy’s work in other parts of the country has been both intentionally unsettling and aimed at enlisting residents as art-makers on behalf of a greater awareness. Here in Santa Fe, the focus was on the creation of a long and linear water painting on the bike- and pedestrian-way that runs through the city’s Railyard Park, the site of one of the city’s now mostly disappeared acequias. The first day involved residents in this painting exercise (see photo), meant to illustrate and make present the acequia waters, through the use of water-soluble chalk paints.

It was a welcome chance to express my innate love of water (in a way adults are rarely allowed). As Levy says, few of us get the chance to express ourselves in this way. Everyone benefits, she tells me, “from this very experiential, kinetic drawing with a pivot in your whole body.”

Imagining the creation of a new acequia by merely drawing it was itself a kind of act of mind-dunking or -diving, Levy was ever encouraging, providing guidance about water-shapes and forms we might repeat or model after. Some of these shapes tie directly to the physics of water movement, especially the Kármán vortex streets. These are swirling and curling vortexes that Levy tells us can be found in every aspect of nature and human life, from the fluid dynamics of ocean currents and weather systems, from hurricanes to daily cloud cover, and, as Levy tells us that day, even the movement of blood in and out of the chambers of the human heart. We were inspired that day to channel the patterns and life forces we see and perhaps pay little attention to, to manifest them and make them visible.

Levy’s works are mostly ephemeral and temporary, as was the case with the water-soluble chalk paint. “I’m trying to conjure up the sense of an old path of an old acequia,” she says. It is a fitting medium given the fleeting nature of water itself. Reflecting on this missing water, Levy believes, is a critical part of learning about a place, of “knowing where you live,” she says.

I have been a fan of Levy’s work for many years. Her body of work includes, most arrestingly, the Dendritic Decay Garden in Philadelphia. It is a project that seeks to set in motion a process of ecological healing, in this case, creating a web of curated cracks that allow water to seep in and be cleansed before eventually joining the river. The Association for Public Art describes the project this way: “The large fissures cut into the asphalt create a ‘grooved platter’ that channels rainwater and furthers the weathering of the concrete landscape”.[4] The actions of freezing and thawing, and growth and decay, intentionally open up the impervious world of the cityscape to convert it to a natural stormwater sponge and a network of micro-wildernesses (to use E.O. Wilson’s words). It is appealing to think that such acts of water art not only inspire and educate but also set in motion natural processes that help to restore and regenerate the watershed.

Another of my favorite projects is the Rain Ravine, an outdoor water feature designed into the outer edge of the Frick Environmental Center in Pittsburgh. The water feature collects rainwater from the structure and sends it down into a series of stone levels meant to simulate the passage of Pennsylvania rainwater from mountain to coast. The short film below describes the impressive biophilic design elements of the Center (the exterior pattern of wood siding is meant to mimic a natural forest, for example), and demonstrates vividly how this water feature works when it rains (at about the 3-minute mark).

On the last two days of the Santa Fe event, Levy engaged high school-aged students at the New Mexico School of the Arts. One could not be more optimistic about filming their creative artistry in real time.

First-hand participation in the management of water, as the acequia story shows, also helps to highlight the profound changes underway, largely a result of climate change. Northern New Mexico, along with much of the Southwest, continues to struggle with a long-term drought, with a diminishing snowpack, and rising temperatures. The Rio Grande, into which the Santa Fe River flows, is experiencing serious ecological change and actually ran dry in early July. The implications of this increasing water scarcity are daunting, to be sure. The truly majestic “bosque” or canopy forest of cottonwoods is, as a result, under considerable stress. Decline in groundwater levels and reduced intermittent flood conditions that are necessary to sustain new cottonwood seedlings have meant this riparian forest is changing dramatically. As I write these words, news arrives that the Rio Grande has run dry over the stretch that passes through Albuquerque, sixty miles to the south.

There is no doubt we must do a better job managing the water we have, whether in New Mexico or Virginia. That includes thinking more systematically about the over-abundance of water at times (floods) and how to manage land use patterns to at once reduce human risk and exposure, but to creatively harness these pulses to restore groundwater resources. And here there are acequia lessons and potential applications.

Designing city streets to steer a steady flow of rainwater into life-sustaining water to increasingly thirsty urban trees and forests, as some cities are now doing, ala Mendoza, is one idea. And in the process, as Bernard reports, they create a more natureful and interesting city: “Being able to see and interact with this [water] infrastructure makes it more relevant in our lives and provides an opportunity to learn more about it and the essential role it serves”.[5]

We have been immensely impressed with the ways this city has sought to maximize the emotional power and import of the limited water it has. Walking and sitting along the Sante Fe River, immersed in its beauty, movement, bird-life, and audible presence, add immeasurably to the life of this city. The carefully designed small waterfalls maximize this visual and audible impact. The Acequia Madre, and the other remaining acequias, when their water is running, provide a similar set of sensory thrills.

Traveling back to Virginia in early May, we crossed increasingly larger rivers as we headed east. The size and width of these rivers were, even after our relatively short time in the West, striking: the North Canadian River, the Arkansas, the Mississippi, the Ohio, and eventually the James, close to home. The abundance of water is something many Easterners take for granted; we certainly waste much of it and fail to understand its ecology, beauty, and preciousness. At a time when abundance seems to be getting all the attention, we must acknowledge, at least when it comes to water, the reality of scarcity. We would certainly benefit from more careful use everywhere, as well as the lesson of engaged and democratic methods of water governance that New Mexico’s acequias provide.

Tim Beatley

Charlottesville

[1] See Lamadrid and Rivera eds, Water for the People: The Acequia Heritage of New Mexico in a Global Context, Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2023.

[2] Lourdes Medrano, “Climate Change Puts New Mexico’s Ancient Acequia to the Test, Audubon, October 12, 2021, found here: https://www.audubon.org/magazine/climate-change-puts-new-mexicos-ancient-acequias-test

[3] Andrew Bernard, “Looking to the Past for Solutions for the Future: A Comparative Study of the Acequias of Two High-Desert Cities,” in Lamadrid and Rivera eds, Water for the People: The Acequia Heritage of New Mexico in a Global Context, Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2023.

[4]Association for Public Art, “Dendritic Decay Garden,” found here: https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/dendritic-decay-garden/

[5] Bernard, p.213.

Leave a Reply