Nature consistently emerged as a place of refuge, offering moments to pause, reflect, and retreat from the city’s fast-paced life.

about the writer

Marthe Derkzen

Dr. Marthe Derkzen is a researcher and lecturer with the Health and Society chair group. She studies urban nature from a social justice perspective with an interest in climate adaptation, local food, healthy neighborhoods and stewardship of the commons.

about the writer

Agnès Patuano

Dr. ir. Agnès Patuano is an Assistant Professor in Landscape Architecture and Spatial Planning in Wageningen University (The Netherlands) and an expert on landscape architecture and human health.

about the writer

Vanya Bisht

Vanya Bisht works at the intersection of socio-ecological systems and science and technology studies, exploring how diverse knowledge systems and values shape human-nature relationships in cities. She is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Future Cities Institute in the University of Waterloo, Canada.

about the writer

Yuliya Dzyuban

Yuliya Dzyuban’s work focuses on developing solutions to mitigate urban heat and enhance resilience and livability amid climate change and social inequity. Her research spans some of the world’s hottest cities, including Singapore, Phoenix, and Hermosillo, informing climate-sensitive design and planning policies. She engages local communities in mapping and understanding lived experiences of heat by leading participatory thermal walks that foster awareness of how urban design influences microclimates and thermal comfort for both people and ecosystems.

about the writer

Alessandro Arlati

Alessandro Arlati is an urban planner and researcher with 4 years of experience in Horizon2020-funded projects. After a bachelor’s degree in architecture at the Polytechnic University of Milan (Polimi), Italy, he studied urban planning in a double-degree master’s programme between Polimi and HafenCity University. His interests range from multi-level governance to sociological network analysis. He worked in the CLEVER Cities project, focused on the co-creation of nature-based solutions in deprived urban areas, and in the REPAiR project, which worked with the concept of the circular economy to improve material cycles in peri-urban areas.

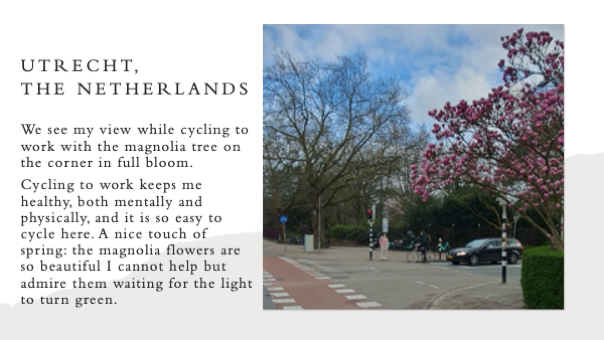

What constitutes a healthy living environment? What environment keeps us healthy looks different across the globe, as it depends on both cultural (e.g., uses, behaviours) and spatial (e.g., ecosystem, climate, infrastructure) factors. This motivated us to ask participants of The Nature Of Cities Festival 2024 to take a photograph and answer the question: what outdoor environment keeps you healthy in your everyday life?

In a virtual and an in-person Photovoice (see box 1) group session, we discussed participants’ photos to identify differences and commonalities in our interpretations of a healthy environment. Our aim was to derive design recommendations based on the diverse perspectives represented in the pictures. Photovoice enabled us to engage with the diverse audiences at the TNOC Festival, across geographical and professional boundaries, to facilitate discussions on healthy urban environments. The Photovoice exercise and group discussion are a follow-up of a session and essay about designing urban green spaces for health and wellbeing that we organized at The Nature of Cities Festival in 2022.

| Photovoice

Photovoice is a participatory research methodology that uses photographs to elicit participants’ perspectives, emotions, and experiences on a particular theme. In a typical Photovoice activity, participants are given a prompt related to a research topic and asked to take photographs at their convenience that depict their connections to the prompt. This is followed by individual or group discussions among the researchers and participants, where participants reflect on their photographs and their relation to their experiences with the research theme. Photovoice is a versatile methodology that can easily be used with a diverse range of participants across age, gender, regional, and professional backgrounds: it uses photographs as a medium of discussion that most people are familiar with and have fun using. Since Photovoice allows participants to take photographs at their own time and convenience, it can be easily adapted to a variety of research topics, including sensitive subjects such as health and relationships with urban spaces. In many cases, photos produced by participants offer deep, nuanced insights into their everyday experiences, which can include stigma, marginalization, and recovery (see Resource section, 2). |

Participants were prompted to take a photo of an outdoor environment that is part of their daily life and that they believe contributes to their health. In the group discussion, we started with a round in which each participant showed their photo and answered the following questions:

- Where is this photo taken?

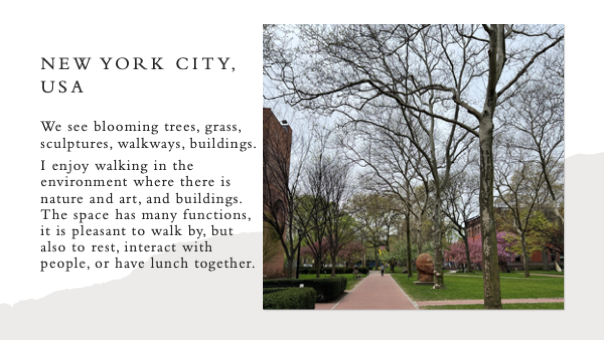

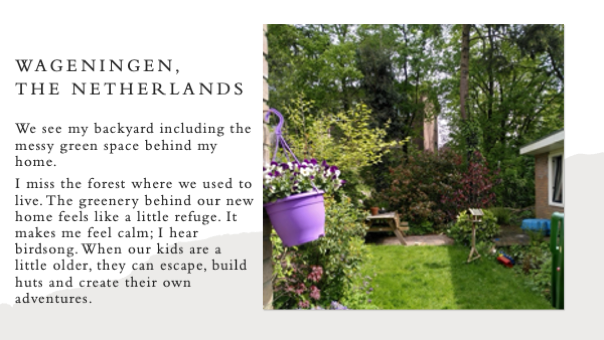

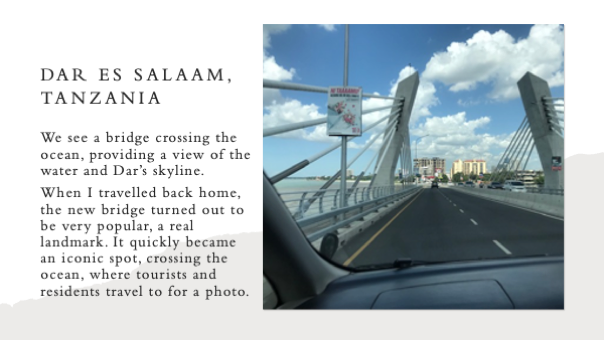

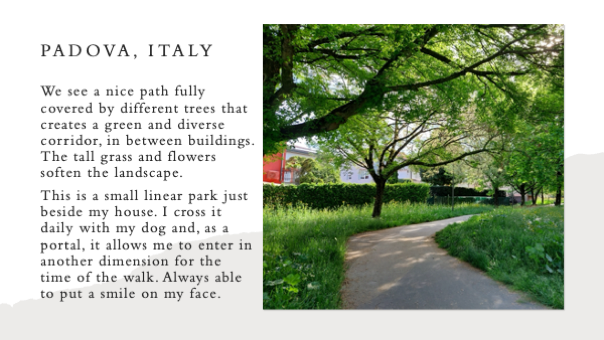

- What do we see?

- Why did you choose this photo?

- How does this relate to your health and well-being?

In the second round, everyone was asked to carefully look at each photo individually and, using sticky notes, identify design elements for health. After this individual exercise, we got back together for a third round to discuss commonalities and differences between the photos and the design elements.

Photovoices

Design elements

Commonalities

All photos represented natural elements in different forms, particularly trees, flowers, and a variety of vegetation layers, but also, in one case, water. Contact with wildlife, either birds or insects, and particularly native species, was a recurring point in the discussions. Another commonality of the photos was their location, often on a commuting path, showing the importance of these spaces in our daily lives. The majority of photos were taken in public spaces, although 3 out of 10 participants had brought pictures of their private gardens. One striking commonality was that in most pictures, no human presence was visible. Additionally, despite most photographs showing public spaces, only 2 out of 10 showed the presence of cars.

Differences

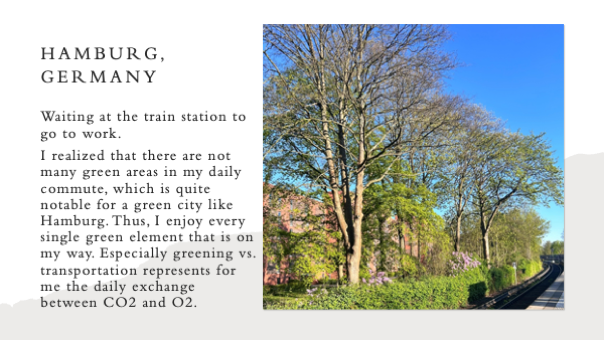

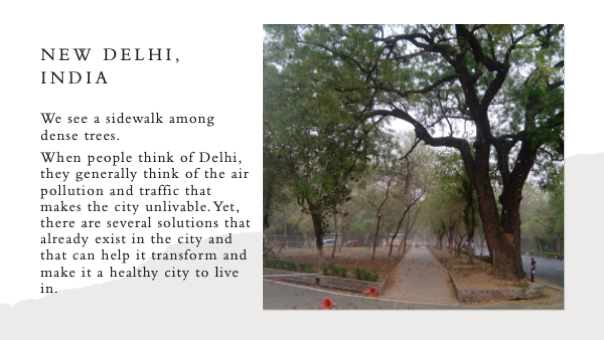

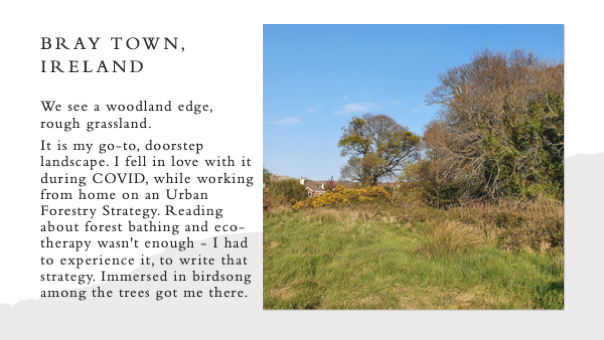

The photos captured a diverse range of urban environments and climate conditions, reflecting the varied backgrounds of participants—from the small coastal town of Bray, Ireland, to the bustling metropolis of New Delhi. As a result, the environments depicted in the photos varied greatly. Although all photos showed natural elements, these ranged from formal to informal, from nature to be touched to nature to be seen, and from nature hiding the building to nature and buildings working together in synergy. The one photo that did not feature vegetation depicted a landmark well-known to both residents and tourists (in Dar es Salaam), illustrating how built elements can contribute to a sense of place and well-being when they become locally significant.

Meaning

The photovoices shared by the participants illustrated the many ways urban nature supports physical, mental, and emotional well-being. Nature consistently emerged as a place of refuge, offering moments to pause, reflect, and retreat from the city’s fast-paced life. Often, participants captured glimpses of nature encountered during daily commutes through the built environment. These momentary experiences, such as hearing a birdsong or catching the scent of spring blossoms, offered brief but meaningful connections with the more-than-human world. Such encounters not only nurtured emotional bonds with nature but also deepened participants’ sense of connection to the city itself, especially through familiar, endemic trees that have become part of the city’s identity in their minds.

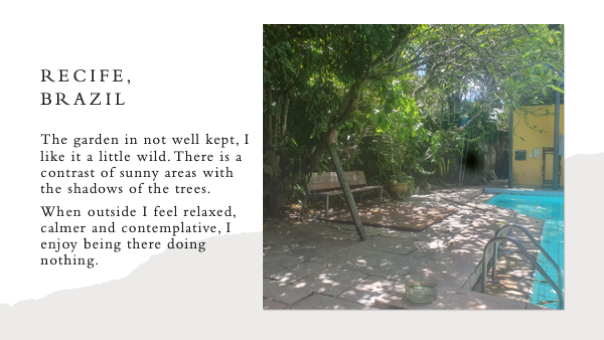

In addition to nature encountered in transit or public spaces, many participants also shared photographs of nature within private or semi-private spaces, such as their homes, backyards, or shared neighborhood areas. These carved-out pockets of nature offer spaces for cultivating meaningful urban lives, whether by growing and sharing food, providing opportunities for youth to play and explore, or fostering a sense of “wilderness” within an otherwise built-up city. Participants were especially eager to share the personally significant plants and vegetables they had chosen to grow in their home gardens, often explaining the reasons behind their emotional attachment or the meaning those plants held for them (see the photostory from Chile).

Design guidelines and recommendations

Although the small sample of photos does not allow the formulation of blanket design guidelines for the universal creation of outdoor spaces able to support the health of everyone, we have summarized our findings into a set of general recommendations:

- Create multifunctional environments to foster everyday contact with nature and support active and restorative mobility

- Design landscapes that integrate with daily routines, such as green verges near homes or paths used for commuting. Keeping in mind the ordinary, not only the extraordinary.

- Create safe, accessible, and pleasant cycling and walking routes that pass through green spaces.

- Prioritize views of greenery from these living spaces to provide moments of joy and contemplation.

- Combine nature with art, architecture, and social spaces to create landscapes that are engaging and inclusive.

- Provide seating areas, shaded spots, and flexible-use spaces to encourage social interaction and rest.

- Encourage informal and wild green spaces to strengthen urban biodiversity

- Allow for “messy” and less-maintained green areas to create biodiversity refuges and personal sanctuaries.

- Integrate informal play spaces where children can explore, build, and connect with nature.

- Design plantings that support native pollinators, such as bees, and incorporate edible plants when possible.

- Preserve woodland edges, rough grasslands, and other ecotones to enhance ecosystem resilience.

- Create multisensory experiences

- Incorporate diverse seasonal elements (e.g., blooming trees) to enhance sensory experiences.

- Encourage wildlife (e.g., birds, insects) to provide dynamic auditory experiences and minimize artificial noises (e.g., traffic).

- Provide green and blue elements at different scales

- Prioritize a network of green and blue interventions at different scales, from private households to city scale, to mitigate urban stressors like air pollution and traffic noise, as well as climate-hazardous conditions (heavy rain, etc.).

Wrap up

Through their photographs and reflections, participants revealed multifaceted relationships between physical spaces and health. While the documented spaces varied by type and geographical location, several key themes emerged. Participants identified meaningful interactions with nature in both public and private spaces, either through incidental or intentional encounters. During incidental encounters in public spaces, such as daily commutes, nature provided shelter from the elements and anthropogenic pollution and noise, as well as offered aesthetic pleasure through diverse colors and shapes. Intentional interactions that often happened in private gardens or public spaces that were either intended for recreation or were not actively managed, offered refuge, wildlife encounters, and provided multi-sensorial experiences. These natural spaces fostered feelings of wonder, peace, and rest.

Participant reflections also highlighted several features of the built environment that support health. Walkways and bike lanes were mentioned as enablers of physical activity. Art and landmarks created a sense of familiarity. Benches and seating areas were associated with rest.

Based on these findings, we developed health-focused design principles that can be adapted across diverse geographical and socio-cultural contexts. These design guidelines prioritize connection between the built environment and natural elements, promote connection with biodiversity through supporting urban rewilding aesthetics of public and private spaces, and provision of ecosystem services, as illustrated in the diagram below.

However, it is important to remain aware of the diversity of the social, political, cultural, and ecological contexts, avoiding the one-size-fits-all narrative. Our guidelines do not have a vocation to be universal, as they are based on our participants’ specific visions, and should be applied in a contextualized way, remaining sensitive to diverse populations’ needs.

Marthe Derkzen, Agnès Patuano, Vanya Bisht, Yuliya Dzyuban, Alessandro Arlati, and Jean-Marie Cishahayo

Arnhem/Nijmegen, Wageningen, Kitchener, Singapore, Hamburg, and Ottawa

Also with contributions from: Sofia Schmidt, Circe Monteiro, Ilaria Doimo, and Aidan French

Resources

On Photovoice as a method:

- Implementing Photovoice in Your Community by Community ToolBox

- Adeboye, A., Aghalu, U., Onuorah, W., Samuel-Nwokeji, C., Nwanguma, C., Akerele, A., & Wasige, J. (2025). The impact of photovoice on mental health and stigma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Global Public Health, 5(7), e0004272.

Some recent research and applications of photovoice to human and nature connection include:

- Understanding Connections Between Nature and Stress among Concernation- Engaged Adolescents Using Photovoice Methodology (2023). Nature shows us different aspects of beauty, helps us relieve stressful experiences by balancing our senses, gives us space to find solutions, and to find time to enjoy nature.

- Photovoice: Promising Method for Capturing and Responding to Climate Change (2025). Photovoice is a popular participatory research method for instigating critical reflection and social change. It does, however, rely on participants being able to photograph and capture the phenomenon under study.

- The impacts of Nature Connectedness on Children’s Well being: A systematic Review (2022). Direct or indirect well-being of children and adolescents’ natural connectedness is are growing societal interest. However, the concepts, the conceptualization and operationalization of the nature of connectedness, well-being, and their interaction, as well as the empirical methods used to analyze them, vary remarkably.

- How Emerging Adults Perceived Elements of Nature as Resources for Well-being: A qualitative Photo-Elicination Study (2022). The thematic analysis revealed four distinct received pathways connecting these elements of nature: the pathways connecting nature to wellbeing, including systematic nurturing, building social glue, maintaining a positive, and centering yourself.

Leave a Reply