An exhibition by Robin Lasser and Marguerite Perret

Originally produced by Oklahoma State Museum of Art,

adapted and digitally-curated for The Nature of Cities by the

Forum for Radical Imagination on Environmental Cultures (FRIEC).

Introduction

“…from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being evolved.”

— Charles Darwin

We human beings are part of this ever-evolving world described by Darwin. Indeed, as much as anything found in Darwin’s journals, we are among the amazingly beautiful and wondrous species. Yet our destructive influence can sometimes seem in opposition to this beauty. Will humans follow the more ominous Darwinian path, or might we put our thinking minds to use, finding ways toward the “beautiful and wonderful” path?

Which side of the human story will prevail?

In this exhibition, science and art are used side-by-side, allowing us to peer deeply into both sides of this human dichotomy through our relationships with water. After multiple years of interdisciplinary research and production, artists Robin Lasser and Marguerite Perret find that we certainly have some work to do in order to live up to our potential as an earth-bound species.

Yet they also uncover a spectacular, uniquely human beauty in — of all places — sewage plants, rain storms, and laboratories.

The experience below is a curated tour of three selected galleries from what is an extremely far-reaching exhibition produced by Lasser and Perret at the OSU Museum. The selected works here at The Nature of Cities, relate intimately to our human relationships with water in cities. Through the dual-lens of science and aesthetics, we explore the effect our actions have on our ecosystems. At the same time, we imagine new ways of seeing ourselves in relation to these ecosystems — ways that allow us to share more fully in its beauty.

These ways of seeing are not only inspirations, but hints at how we can each shift our own actions toward the ecological. In viewing these works then, we challenge you to find your own inspiration and action, in the poetry and fantastical world of Weather Report, in the sculptural forms of a Strangled Tangled Bank, and in the beautiful absurdity of a Theater of Water Reclamation.

Thank you for joining us, and please enjoy the journey through this virtual exhibition.

Patrick M. Lydon

Arts Editor, The Nature of Cities

Weather Report

Scientific reports and news headlines alike, can make ocean tides, storms, and global warming seem too big, too overwhelming, or at times, too remote from our own life. But relationships with the environment can be highly personal, too.

In the Weather Report gallery, artist Robin Lasser works with multiple artists from the United States and Japan, and most touchingly, with her own mother, who passed on as work on this exhibition came to a close. Here, Lasser brings us into a world of weather that is poetic, emotional, and filled with unfathomable beauty and wonder.

Weather Report Installation

Robin Lasser

dedicated to Phyllis Lasser

January 8, 1924 – April 24, 2020

This installation holds multiple tensions—the tensions brought about by global warming, longer droughts, rising seas, and stronger storms as well as the incomprehensible tensions between mother and daughter, the mystery, tears, and love.

The genesis of the work in this gallery was the Signaling Water: Multi-Species Migration and Displacement exhibition, presented in Osaka, Japan in 2019. While installing the show, there was a typhoon warning that threatened to close down the entire exhibition. In this milieu, the collective Typhoon Queens was born, whose work you will see in several places throughout the gallery.

Images (left to right):

Typhoon Queen installation view, Masahiro Kawanaka, Robin Lasser, Takuma Uematsu

Blue River and Sturgeon Mandala, Robin Lasser

Weather Report installation view

The typhoon primarily hit Tokyo, just north of Osaka; nevertheless, in Osaka the clouds were shaking. As they were shaking, the sacred Sumiyoshi River that flows from one of the oldest water-related shrines in Japan, rippled with incredible patterns from the rain and elements striking the river’s surface. These patterns, in this case created by rain striking river water, evoked stained-glass windows from ancient cathedrals, patterns scratched onto cave walls, bas-reliefs motifs on Egyptian tombs, and temporary Navajo sand patterns created for healing ceremonies.

The weather, the rain, mirrored the creative imagination of humanity.

Returning from Osaka to visit Phyllis, her 96-year-old mother, Robin started to read some poetry aloud that Phyllis had written forty years ago. Phyllis and Robin had wanted to create a poetry and image book almost four decades ago. That day, re-reading Phyllis’s extraordinary words of wisdom, and the observations that connect bodies to place and souls to the universe, Phyllis and Robin decided to collaborate at last. They bonded over the shared sentiments in their work, produced at the same age in different eras.

The film below is the moving image companion to the book, the soundtrack embracing the ambient sound of a typhoon, along with Phyllis Lasser’s poetry read by Alan Schneider, actor and director, recorded in 1984. The film premiered in April 2020 at Art Spot Korin Gallery in Kyoto, the show went ahead, with caution, in middle of the pandemic!

Both the moving images and photographs inspired by Sumiyoshi River patterns explore the relationship between science, nature, art, and spiritually by documenting the moment when rain ripples across another body of water. The imagery, when mirrored, resembles the patterns utilized in art and architecture, throughout time, around the globe. The photographs and video are reminiscent of mandalas, traditionally utilized in healing settings. This added layer, healing, inspired the project to turn both the relationship between mother and daughter and to the planet itself, and what a need for healing means in those contexts.

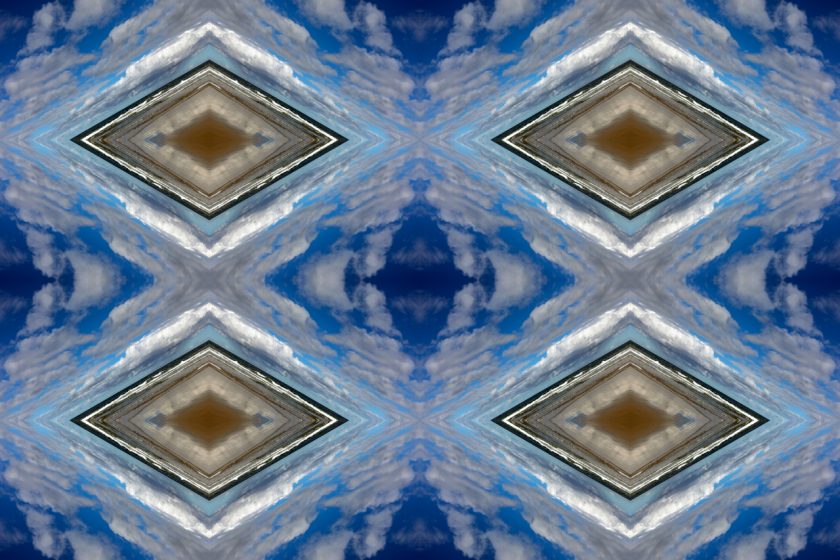

Images (left to right, top to bottom):

Aquarium Waste Falls; Tides Waves; Sea and Sky Mandala Version Three

Sea and Sky Mandala Version One; One Eye Closed but Not to Sleep

Robin Lasser

On April 22, 2020, a printed version of the poetry book was delivered to Robin’s home in Oakland at 8:00 PM. Robin drove all night, arriving in La Jolla with book in hand, the following morning. There was a bit of a rush—the family had learned just days before that Phyllis had decided to exercise her Dying with Dignity option.

On April 23rd, the day before her chosen date of death, Phyllis lavished her attention upon the final draft of the book, the film, and the photographs included in this exhibition. Phyllis and Robin went through this process together, the process of making this project and the process of dying.

Phyllis died during the pandemic, so only a few members of the family, due to the shelter-in-place mandate, could return home to be with her during her final few days. Phyllis ushered Robin into life; Robin pledged to see her though death. In those final moments, Robin kissed her mother tenderly, and a smile formed on Phyllis’s lips, radiant. The expression lasted just an instant, and then Phyllis died in Robin’s arms.

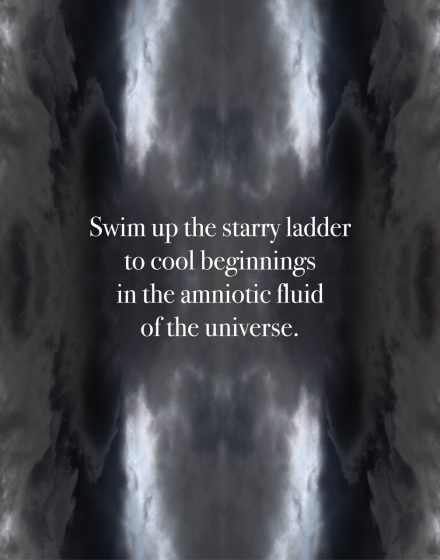

Images (left to right, top to bottom):

Reaching Deep for Wellsprings Now Empty; Peel the Green Mountain from the Blue Page;

Sea Foam: Death is Closed Eyes and Another Awakening; Amniotic Fluid of the Universe

archival dye-infused metal photographs, Robin Lasser

Phyllis’s smile is not all that flashed on April 24th, however.

The unseasonably heavy rains in La Jolla this year, the rains that marked the lens-based work done for the exhibition, also created a nutrient-rich overflow into the sea. Plankton grew, and the red tides followed. Those single cell critters, called dinoflagellates, glow neon blue in response to physical disturbances in their space, as a form of “protecting” themselves from predation.

By day, the windows of Phyllis’s house looked out onto red/brown waves, and by night, including the night of Phyllis’s death, they looked out on the blue glow of dinoflagellates in the sea, providing a lightshow send-off. Phyllis’s spirit was released into the Pacific.

The Strangled Tangled Bank

Human beings have produced technologies, products, and new ways of understanding our place in the universe that, so far as we know, no other living being could even imagine. With these tools, unfortunately, we have also disrupted the health and stability of our environment in ways that no other living being would likely want to.

Such is the strangled tangled bank that artists Marguerite Perret and Bruce Scherting help us navigate, presenting some wondrous views and discoveries at the borders of science and art.

Transmutation Still Life

Nature Study Tables

Marguerite Perret and Bruce Scherting

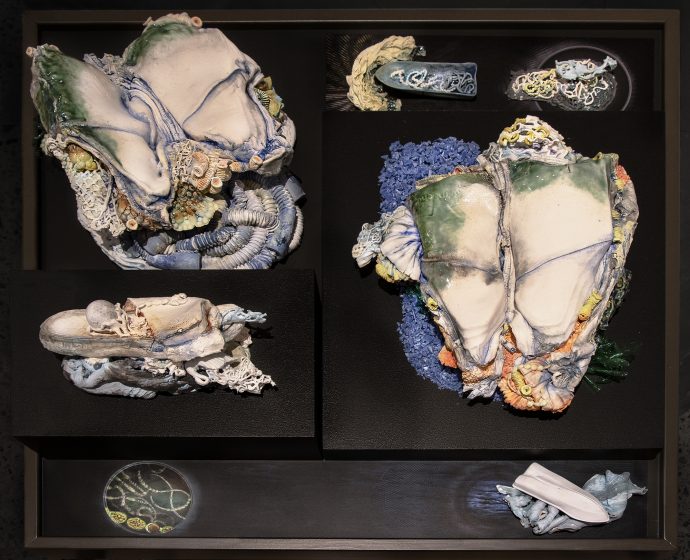

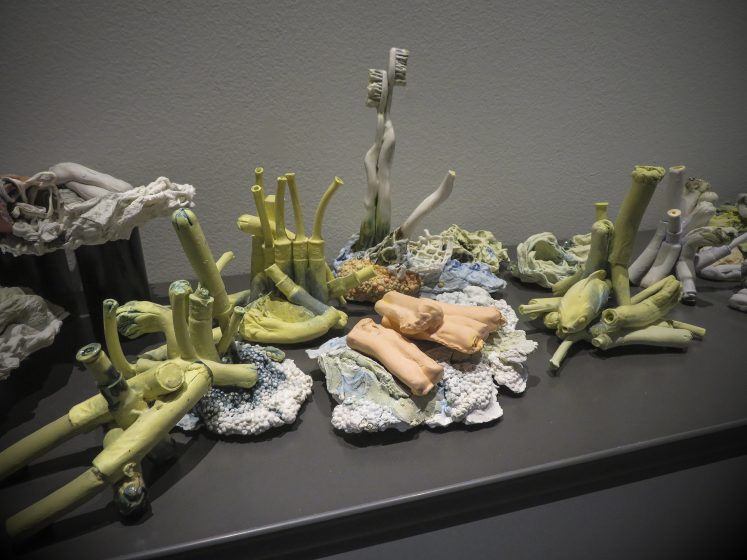

The following is a mixed media installation, with porcelain slip cast, press molded, and ceramic burnout specimens of anthropogenic debris found along fresh waterways and lakes. In the tradition of a museum study collection, a variety of related objects are placed on low tables, in boxes, and on risers for inspection.

The relationship between these objects to each other and the collection as a whole is implied and further suggested by graphic and photo-based images that line the table beds.

Transmutation Study Collection installation view

Marguerite Perret and Bruce Scherting

2019—present

Transmutation is an old word for changing one thing into another. It is often associated with alchemy (lead into gold), but it is also an expression for changing one species into another. The term was replaced in 1872 when Charles Darwin used the word evolution for the first time in his sixth edition of the Origin of Species. Clay (the porcelain used here as a medium) also goes through a process of transmutation in the firing process. And notably, in a very real way we are living in an era of transmutation, in part because of the COVID-19 virus, but also because the world around us is changing so fast, giving rise to pandemics and other challenges associated with climate change.

All living things are chemists, bioelectrical engineers, manufacturers and fabricators. The snail synthesizes a shell by metabolizing raw materials from its environment. Ancient cyanobacteria created a breathable atmosphere releasing oxygen as a byproduct of photosynthesis. And so life on land exists thanks to the alchemical talents of these tiny creatures. But cyanobacteria can also produce harmful compounds when there is an excess of nutrients in the water causing a ‘bloom.’ These cyanotoxins make humans and wildlife sick, kill fish and–as they move down stream–create dead zones in ocean. Humans likewise take resources from the environment and modify them creating new products and waste streams, some of which are beneficial and others disastrous to the environment. The difference is that humans can understand the consequences of their actions.

Transmutation Study Collection installation view

Marguerite Perret and Bruce Scherting

2019—present

The porcelain specimens, mixed media objects and images on display appear to be in various states of decay. They are torn, broken and ruptured; encrusted with nettings and fibers, casts of zebra mussels, worm and leech like creatures, suggestions of biofilms and populated with other speculative macro and microscopic transplants and colonizers. Yet despite their organic appearance, all of the ‘specimens’ in this collection are rooted in the world of trade and mass consumption. What appears to be anemone like creatures are the patterns found in iconic ash trays. Plant forms are ceramic burnout remnants of dead houseplants from the local home improvement store. Casts of found objects include many lost shoes, boating paraphernalia, fishing gear, single use plastic packaging and the ever-ubiquitous plastic bottle.

In a very real way, we are living in an era of transmutation because the world around us is changing so fast, giving rise to pandemics and other challenges associated with habitat disruption, loss of biodiversity and climate change.

Theater of Water Reclamation

Water has a cyclical life. The things that flow down our drains never really leave. Some of them — bacteria from our own gut — actually help the process of water reclamation, while others — plastics, pills, hygiene products — continue to be harmful in the ecosystem even after water is treated.

This is not a topic we tend to think about, let alone sing and dance and make sculptures about. Yet, that is just what Lasser and Perret do, enlisting the help of water scientists and water reclamation plant workers, no less.

Welcome to the Theater of Water Reclamation. If you have never seen a musical operetta about sewage treatment, you are in for a treat.

Wastewater Is Us: A Complex System

Marguerite Perret

The common meaning of the word abject is something that is base, low, vile, or miserable and wretched. Abject is opposite of the exalted, the beautiful. An older meaning is to cast aside or cast off.

Contents at wastewater treatment plants are literally the substances we want to send away and so that we never have to think about them again. These include the material of our own bodies, and the waste it generates– expelled, shed or sloughed off; together with kitchen debris, grease, dirt, cleaning solutions and other household chemicals, personal hygiene products, prophylactics, old medical prescriptions, and the occasional dead goldfish.

Cloacina in Triplicate

Marguerite Perret and Bruce Scherting, 2020

Archival photographic digital prints on Aluminum

They accumulate at the wastewater treatment plant where they are transformed into a complex system, a unique series of habitats that are created by our bodies and their functional activities. Because most of the flora and fauna comes not from the wastewater treatment process, or the air, but from our skin, our gastric intestinal tracks, the microorganisms that we bring into our homes and then clean and release into the waste stream through the sink or shower or washing machine. The benign organisms are encouraged to help breakdown the solids in wastewater and purify the water. It is an act of genuine alchemy, a transmutation of a base substance into something more precious than gold– potable water.

The wastewater treatment plant offers no social hierarchies, it is ultimately purely egalitarian. My microbes, DNA, skin cells (and worse) mix with yours, and this can tell us much about our community. During the COVID-19 pandemic, health officials began to test wastewater to determine local spread of the virus.

Toys and Blooms installation view

Marguerite Perret, 2020

Porcelain and mixed media with digital images, 2020

Songs, Poems, and Interviews

Robin Lasser

featuring staff of the City of Stillwater Wastewater Treatment Facility

The physical presence of the architectonic setting is captivating, as is the process of turning human waste into water—the only new source of fresh water on the earth. The wastewater treatment environment houses the community’s DNA and is a place that reveals so much about the personal lives of the community. The wastewater treatment staff members care deeply. Art Lage, Senior Lab Technician at the Wastewater Treatment Plant in Stillwater, states, “It’s all about saving the planet and saving the water. Making sure it’s here for future generations.”

All the staff members at the wastewater treatment plant in Stillwater are deeply committed to serving the community, education, and sustaining our environment. They sport other attributes as well; who would have guessed that the former superintendent, Lou Ann Fisher, loves to sing? In the film, Lou Ann provides an on-site tour of the plant, singing musical compositions she has written, about each stage of wastewater treatment at the Stillwater plant. Lou Ann is also a talented seamstress and fabricated the lush red velvet theatre curtain framing the film in this installation.

Dondi Earnest, wastewater treatment lab technician, writes a poem a day. He says, “the reason I write poetry is that I know when I pass from this earth, that I won’t leave anything to my family as far as property, or money, or nice cars, so I try to write a poem a day to leave that as my legacy.” In the lab, Dondi reads a poem revealing a personal relationship to the plant and the work of a lab technician. Dondi also plays guitar and is a singer/songwriter.

Theatre of Water Reclamation

by Robin Lasser, 2020

Drone footage by Victoria Alexander, student,

Unmanned Systems Research Institute,

OSU Sewer Operetta by Dan Gold, Theatre Lighting Engineer

Needless to say, wastewater treatment is filled with creatives and educators who powerfully informed the film’s depiction of the art and science of the waste stream.

Exhibition Credits

Originally produced by Oklahoma State Museum of Art, this exhibition has been adapted and digitally-curated for The Nature of Cities by the Forum for Radical Imagination on Environmental Cultures (FRIEC).

Lead Artists

Robin Lasser

Oakland, California

Marguerite Perret

Lawrence, Kansas

TNOC Production

Project Direction / Curation: Patrick M. Lydon

Web Development Support: Karen Tsugawa

Additional Support: David Maddox, M’Lisa Colbert, Carmen Bouyer

OSU Museum Production

OSU Museum Director / Chief Curator: Victoria R. Berry

Curatorial Staff: Kristen Duncan, Christina Elliott

With Thanks to

The Prairie Arts Center, Stillwater

Students and Faculty in the OSU Environmental Sciences Graduate Program

(Dr. Scott Stoodley, Director)

Students and Faculty in the OSU Unmanned Systems Research Institute

(Dr. Jamey Jacobs, Director)

Students and Faculty in the OSU School of Architecture

(Faculty mentor & collaboration coordinator, Paolo Sanza)

The Office of the OSU Vice President of Research

(Dr. Kenneth Sewell, VP)

OSU Center for Sovereign Nations

Oklahoma Water Resource Center

OSU Integrated Biology

OSU Allied Arts

Freshmen in Transition in the OSU Ferguson College of Agriculture

OSU Department of Art, Graphic Design, and Art History

OSU Edmon Low Library Science Cafe

OSU Science Education

OSU Environmental Engineering

OSU Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management

The Lake McMurtry Foundation

(Jill van Egmond, Executive Director)

Sara Hill, Cherokee Nation, Attorney General, Formerly Secretary of Natural Resources

City of Stillwater, Oklahoma

Lou Ann Fisher, Former Superintendent, Wastewater Treatment, City of Stillwater currently, Compliance Coordinator for The City of Stillwater, Water Utilities

Jason Tyler, Superintendent, Wastewater Treatment

Kelly Kerr, Student Media Coordinator, OSU School of Media and Strategic Communications

Adam Johnson, Source Water Protection Manager, City of Tulsa

Jason Aamodt, Attorney, Environmental & Social Justice, professor, University of Tulsa, College of Law

Ashley Nealis, Regional Supervisor, Fish Division Kaw Lake, Ponca City, Oklahoma

Oka’ Yanahli Preserve: Nature Conservancy (Blue River), Stillwell

The McGregor Herbarium at the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute

Great Salt Plains Lake

Lake Carl Blackwell

The Weather Report Contributors: Phyllis Lasser, Patrick Lydon, Suhee Kang, Takuma Usematsu, Masahiro Kawanaka

Virtual Tour of the Full Exhibition

For an in-depth look at the full exhibition please explore this 3D virtual tour, produced by the OSU Museum of Art: