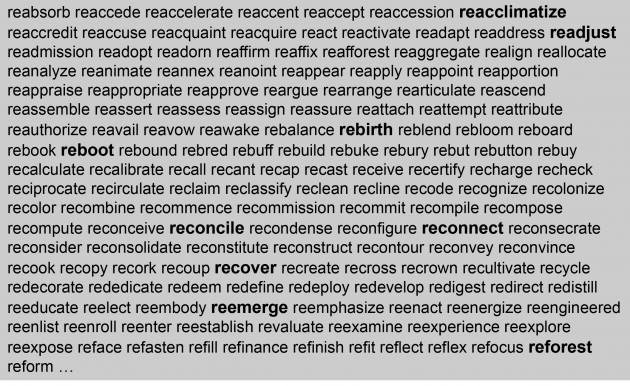

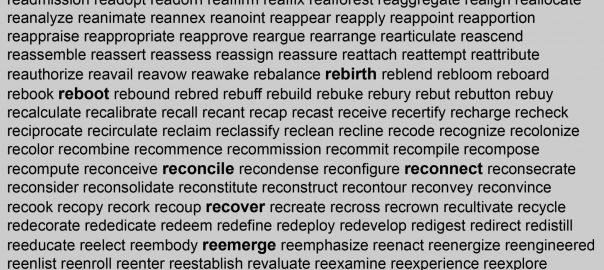

I recently gave a talk at the Horticulture Society of New York’s annual Healing Nature Forum: Planting the Seeds of Health and Sustainability. As could be expected, there was a lot of talk about Hurricane Sandy’s aftermath, and the role of greening. This, of course, is of great interest to me. In my talk, I presented a large number of so-called ‘re-words,’ words that are common in the discourse of urban ecology and related disciplines. These words are interesting because of what so many of them represent—they are ‘do-over’ words, words that indicate another opportunity, a second chance. They suggest alternate endings and outcomes, improved performance or satisfaction, a kind of optimism and hopefulness that a second chance means a better conclusion.

My interest in these re-words stems from the broader philosophical underpinnings of my work on Greening in the Red Zone. Though in a direct sense this work is focused on how humans interact with nature in the midst of and in the aftermath of calamity, and how that interaction is a very important but underappreciated source of resilience and recovery, in a broader sense my work on nature and green spaces in hazard and vulnerability contexts is about playing a hunch. The hunch is that perhaps a key to this idea we are collectively chasing called sustainability is in essence a focused understanding of how our species remembers and reconstitutes relationships with the rest of nature when serious calamity occurs, when the proverbial ‘stuff’ hits the fan.

My interest in these re-words stems from the broader philosophical underpinnings of my work on Greening in the Red Zone. Though in a direct sense this work is focused on how humans interact with nature in the midst of and in the aftermath of calamity, and how that interaction is a very important but underappreciated source of resilience and recovery, in a broader sense my work on nature and green spaces in hazard and vulnerability contexts is about playing a hunch. The hunch is that perhaps a key to this idea we are collectively chasing called sustainability is in essence a focused understanding of how our species remembers and reconstitutes relationships with the rest of nature when serious calamity occurs, when the proverbial ‘stuff’ hits the fan.

What can we learn about how humans relate and reconnect with nature in dire circumstances? And how can that learning about what we do in urgent circumstances be applied to longer term thinking about sustainability and resilience?

In addressing these broader questions, I find that my work is mostly about a kind of archeology of the human social-ecological experience, trying to excavate and peel back the layers of history that have covered over our ecological identity. I am interested in this because fundamentally I believe that our species faces very dark days indeed if we cannot remember our ecological identity and recover a relationship with the ecosystems upon which we depend. Given the challenges facing society and our planet, remembering and recovering our individual and collective ecological identity is of the utmost urgency. However hopeless this endeavor feels in daily life, it is when we are faced with calamity that our withering ecological identity suddenly flushes and blooms, and becomes more clearly important to our survival.

I have documented and expounded on arguments that creation and access to green spaces promotes individual human health, especially in therapeutic contexts among those suffering traumatic events elsewhere.

But what of the role of access to green space and the act of creating and caring for such places in promoting social health and well-being, at neighborhood, community, and even city-wide scales? The forthcoming book Greening in the Red Zone asserts that creation and access to green spaces confers resilience and recovery in systems, from individual human systems to regional and landscape scale systems, which have been disrupted by violent conflict, crisis, or disaster. This edited volume provides evidence for this assertion through cases and examples. The contributors to the volume use a variety of research and policy frameworks to explore how creation and access to green spaces in extreme situations might contribute to resistance, recovery, and resilience of social-ecological systems.

Fundamental to the book is the argument put forward by Berkes and Folke (1998): systems that demonstrate resilience appear to have learned to recognize feedback, and therefore possess ‘mechanisms by which information from the environment can be received, processed, and interpreted’ (p. 21, emphasis added). In this sense, these scholars go further than simply recognizing that people are part of ecological systems, but attempt to explore the means, or social mechanisms, that bring about the conditions needed for adaptation in the face of disturbance and other processes fundamental to social-ecological system resilience. One such social mechanism extensively documented by Berkes and colleagues is traditional ecological knowledge (Berkes 2004; Berkes, Colding, & Folke 2000; Berkes and Turner 2006; Davidson-Hunt and Berkes 2003; see also Shava et al. 2010).

But what other social mechanisms might exist and how does one identify and describe these mechanisms in often urban post-disaster scenarios?

As a result of editing and writing this book, I have become very interested in tracking down the following questions:

What processes or mechanisms might explain the phenomena of Greening in the Red Zone?

Why do people turn to nature and green spaces as sources, sites, and systems of resilience and other re-words?

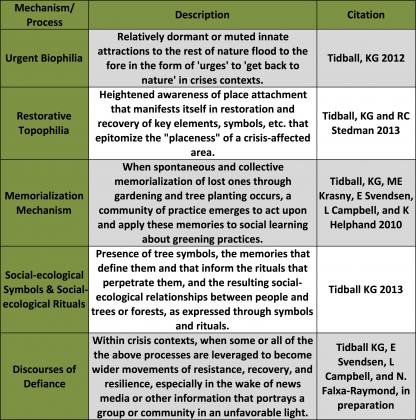

To date, my list of processes/mechanisms that might explain the emergence/persistence of Greening in the Red Zone includes five processes:

(1) Urgent Biophilia

(2) Restorative Topophilia

(3) Memorialization Mechanisms

(4) Social-ecological Symbols and Social-ecological Rituals; and

(5) Discourses of Defiance.

Each of these has been (or will be) explored below, and also in a peer reviewed journal article or book chapter (see below).

I will briefly describe each of these mechanisms in the following paragraphs, and conclude with some caveats and areas for future work.

Urgent biophilia

Urgent biophilia is the affinity we humans have for the rest of nature, the process of remembering that attraction, and the urge to express it through creation of restorative environments, which may also restore or increase ecological function, and may confer resilience across multiple scales. So, when faced with a disaster, as individuals and as communities and populations, we seek engagement with nature to summon and demonstrate resilience in the face of a crisis, we are demonstrating an urgent biophilia.

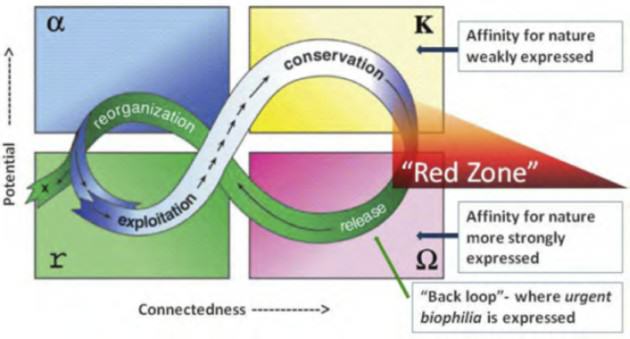

Urgent biophilia represents an important set of human-nature interactions in social-ecological systems (SES) characterized by hazard, disaster, or vulnerability, often appearing in the ‘backloop’ of the adaptive cycle (Holling and Gunderson 2002). Urgent biophilia builds upon contemporary work on principles of biological attraction (Agnati et al 2009) as well as earlier work on biophilia while synthesizing literatures on restorative environments, community-based ecological restoration, and both community and social-ecological disaster resilience.

Restorative topophilia

This mechanism is yin to the yang of urgent biophilia. Here, drawing upon Tuan’s notion of topophilia (literally ‘love of place’), I am emphasizing a social actor’s attachment to place and the symbolic meanings that underlie this attachment. In contrast to urgent biophilia, restorative topophilia is conceived and operationalized as more experiential and ‘constructed’ rather than innate, and suggests that topophilia serves as a powerful base for individual and collective actions that repair and/or enhance valued attributes of place. These restorative greening actions are based not only on attachment—people fight for the places they care about—but also on meanings, which define the kinds of places people are fighting for.

An important implication of the juxtaposition of urgent biophilia and restorative topophilia is the conceptualization of positive dependency. This idea suggest that purely-deficit based perspectives regarding urban social-ecological systems and the human populations within them represent barriers to these systems’ ability to move from undesirable system states into more desirable, sustainable ones. A characterization of issues such as individual ecological identity, human exceptionalism and exemptionalism, anthropocentrism, and resource dependence is offered, in order to better examine notions found in the resource dependency literature, such as the roots of ideas about dependency. This literature is used as a springboard into the possibilities of an antipodal notion of resource dependency that may be applicable in urban contexts, named positive dependency.

Positive dependency as a concept allows us to escape the misguided conclusions potentially drawn by resource dependence arguments that the more that humans depend on natural resources, especially for tangible needs, the more those humans become vulnerable, the more their resilience is compromised. While attempting to recover or reconcile our relationship with nature, we may not need the contradictory message that “the less we are forced to depend upon nature, the better off we are” rattling around our heads. Rather, we can benefit by contributing to the evolution of resource dependency thinking to include the at once simple yet profound idea that “the more we acknowledge our dependence on nature, especially in urban contexts, the more resilient we can be.” Two possible sources of positive dependency in urban social-ecological systems are suggested, urgent biophilia and restorative topophilia. An important conclusion is the recognition of positive dependency as a precursor to the development of a heightened sense of ecological self and sense of ecological place in urban social-ecological systems.

Memorialization Mechanisms

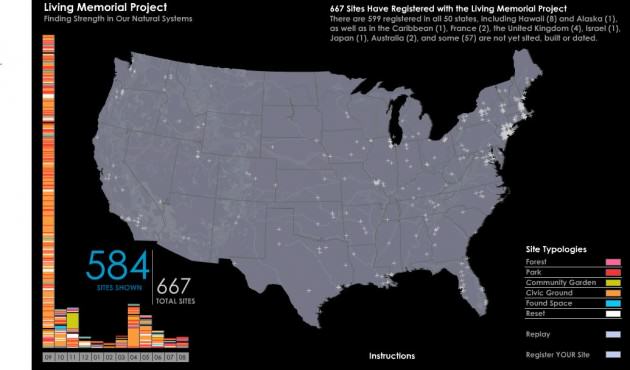

A memorialization mechanism begins right after a crisis, when spontaneous and collective memorialization of lost family members or community members through gardening, tree planting, or other civic ecology practices happens. Then a community of practice emerges to act upon and apply these memories to social learning about greening practices. This, in turn, may lead to new kinds of learning, including about collective efficacy and ecosystem services production, through feedback between remembering, learning, and enhancing individual, social, and environmental well-being.

Social-ecological symbols and social-ecological rituals

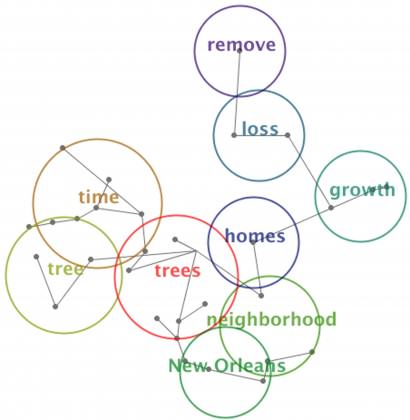

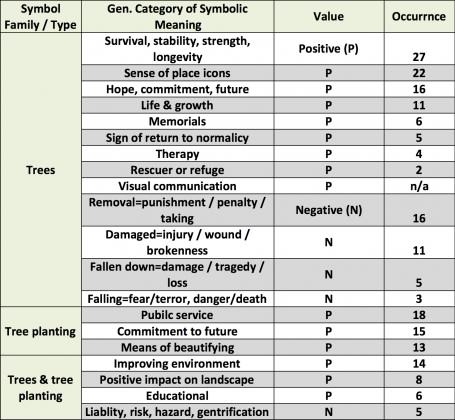

Social-ecological rituals can be understood as storehouses of meaningful symbols by which information is revealed and regarded as authoritative, as dealing with the crucial values of the community (Turner and International African Institute 1968:2; Deflem 1991). In post-Katrina New Orleans, reforestation activities emerged as rituals by which information that represented a counter-narrative to news media and others who spoke of New Orleans as a ‘failure of resilience’ was revealed and regarded as authoritative. Post-Katrina reforestation rituals acted as storehouses of multiple meaningful tree symbols dealing with crucial community values and concepts such as place attachment and sense of place, resilience and resistance, hope and commitment, and survival and stability.

But tree planting rituals and the symbols contained in them reveal more than crucial social values. They are also transformative for human attitudes and behavior, and therefore the handling of tree symbols in ritual exposes the power of tree symbols to act upon and change the persons involved in ritual performance. Whereas New Orleans residents may have been attracted to tree symbols and rituals for reasons such as urgent biophilia, restorative topophilia, positive dependency, biological impulses combined with socio-cultural phenomena, for instance, recalling social-ecological memories (Barthel, Folke et al. 2010), involvement in memorialization mechanisms, or the clear connection of trees to notions of stability and re-birth, my work in New Orleans suggests that subsequent participation in tree planting rituals appears to change the persons involved such that they experience renewed hope, optimism, and sense of commitment to their neighborhood and to their city, important indicators of community resilience.

I have documented how New Orleans residents organized around a particular area of knowledge and activity (trees and tree planting) and developed or reconstituted rituals and symbols that at once reinforced and reinvented the accumulated knowledge of the community via a distributed community of practice centered on trees and tree planting after Katrina. This, I argue, contributed to enhancing a sense of joint enterprise and identity, and therefore contributed to the resilience of the New Orleans social-ecological system. New Orleans residents also continue to plant and steward trees, directly adding to the biomass, future urban tree canopy, and the potential capacity of the urban social-ecological system to produce critical ecosystem services. In so doing tree symbols, tree planting rituals, and those involved in them simultaneously present both a source of and a demonstration of individual, community, and social-ecological system resilience.

Discourses of defiance

As discussed in the above section describing the importance of tree symbols and tree rituals as counter-narratives, the discourses of defiance mechanism is focused specifically on the importance of the use of social-ecological symbols and rituals, memorialization, restorative topophilia, and urgent biophilia to resist or reshape the conversation about where one resides and the people living there. This mechanism was first explored in my work in New Orleans, as residents resisted initial discourses promulgated by the news media essentially “writing off” New Orleans as a failed, or worse, feral city. Residents used many of the mechanisms above to reframe the discourse to reflect a more hopeful, more optimistic, recovery and rebirth oriented conversation.

More recently, working with my colleagues at the US Forest Service Urban Field Station in New York City with funding from the TKF Foundation, we have begun to more deeply explore these discourses of defiance in places like Detroit, Michigan, which despite years of economic decline and disinvestment is emerging as a sort of greening and urban agriculture mecca; and in Joplin, MO which has worked tirelessly and enthusiastically to create a positive and redemptive community response to the aftermath of an EF-5 tornado that destroyed a large swath of the city and killed 161 people. We are currently working in New York City areas hard hit by hurricane Sandy as well.

Conclusion

A growing network of social and ecological scientists argue that change is to be expected and planned for, and that identifying sources and mechanisms of resilience in the face of change is crucial to the long-term well-being of humans, their communities, and the local environment. Yet, as has been pointed out elsewhere, several gaps in the resilience literature persist, including (1) a lack of studies focused on cultural systems (Wright and Masten 2005), (2) relatively few studies that explicitly re-embed humans in ecosystems, and (3) a need for more studies that integrate the theory and science of individual human resilience with broader ecological systems theory and research exemplified by social-ecological systems resilience scholarship (Masten and Obradovic 2008). In introducing the reader to the five mechanisms above, I hope to have outlined an attempt to address these gaps by asking two fundamental questions.

First, I ask “Why do humans turn to greening in the wake of conflict and disaster?”

This question invites us as humans to revisit our relationship with the rest of nature, and to ask ourselves what we may learn from ourselves, given our behaviors in urgent or dire circumstances.

Second, I ask “Of what use might greening in human vulnerability and security contexts be in managing social-ecological systems for resilience?”

This question alludes to application, in planning and policy making fields, in natural resource management, and in fields of disaster preparedness, mitigation, and recovery. Both questions belie a desire to conceptualize human systems as nested within ecological systems, and therefore human resilience as nested within ecological resilience, especially in disaster resilience contexts (Gunderson 2010). The answers to these questions seem to be timely given continuing worries about conflict over access to resources, climate change, and overpopulation and the red zones that will inevitably emerge. The ways in which we as humans reorganize, learn, recover and demonstrate resilience through remembering and operationalizing the value of our relationships with elements of our shared ecologies in the direst of circumstances such as disaster and war hold clues to how we might increase human resilience to new surprises, while contributing sources of social-ecological resilience to ecosystems.

Keith Tidball

Ithaca, New York USA

Citations

Agnati, L., F. Baluska, P. Barlow and D. Guidolin (2009). “Mosaic, Self-similiarity Logic, and Biological Attraction Principles: Three Explanatory Instruments in Biology.” Communicative and Integrative Biology 2(6): 552-563.

Barthel, S., C. Folke and J. Colding (2010). “Social-ecological memory in urban gardens–Retaining the capacity for management of ecosystem services.” Global Environmental Change 20(2): 255-265.

Berkes, F. (2004). Knowledge, Learning and the Resilience of Social-Ecological Systems. Knowledge for the Development of Adaptive Co-Management. Tenth Biennial Conference of the International Association for the Study of Common Property, Oaxaca, MX.

Berkes, F., J. Colding and C. Folke (2000). “Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management.” Ecological Applications 10: 1251-1262.

Berkes, F. and C. Folke, Eds. (1998). Linking social and ecological systems. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Berkes, F. and N. J. Turner (2006). “Knowledge, learning and the evolution of conservation practice for social-ecological system resilience.” Human Ecology 34: 479-494.

Davidson-Hunt, I. and F. Berkes (2003). “Learning as you journey: Anishinaabe perception of social-ecological environments and adaptive learning.” Conservation Ecology 8(5).

Deflem, M. (1991). “Ritual, anti-structure, and religion: A discussion of Victor Turner’s processual symbolic analysis.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 30(1): 1-25.

Gunderson, L. (2010). “Ecological and Human Community Resilience in Response to Natural Disasters.” Ecology and Society 15(2): 18.

Holling, C. S. and L. Gunderson (2002). Resilience and Adaptive Cycles. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. L. Gunderson and C. S. Holling. Washington, D.C., Island Press.

Masten, A. S. and J. Obradovic (2008). “Disaster preparation and recovery: Lessons from research on resilience in human development.” Ecology and Society 13(1): 9.

Shava, S., M. E. Krasny, K. G. Tidball and C. Zazu (2010). “Agricultural knowledge in urban and resettled communities: Applications to social–ecological resilience and environmental education.” Environmental Education Research (Special Issue, Resilience in social-ecological systems: The role of learning and education) 16(5): 325-329.

Tidball, K. and M. Krasny, Eds. (2013). Greening in the Red Zone: Disaster, Resilience, and Community Greening. New York, Springer.

Tidball, K. and R. Stedman (2013). “Positive dependency and virtuous cycles: From resource dependence to resilience in urban social-ecological systems.” Ecological Economics 86(0): 292-299.

Tidball, K. G. (2012). “Urgent Biophilia: Human-Nature Interactions and Biological Attractions in Disaster Resilience.” Ecology and Society 17(2).

Tidball, K. G., M. Krasny, E. Svendsen, L. Campbell and K. Helphand (2010). “Stewardship, Learning, and Memory in Disaster Resilience.” Environmental Education Research (Special Issue, Resilience in social-ecological systems: The role of learning and education) 16(5-6): 591-609.

Turner, V. W. and International African Institute (1968). The drums of affliction: a study of religious processes among the Ndembu of Zambia. Oxford, London, International African Institute.

Wright, M. O. and A. S. Masten (2005). Resilience processes in development: fostering positive adaptation in the context of adversity. Handbook of resilience in children. S. Goldstein and R. Brooks. New York, New York, USA, Kluwer Academic/Plenum: 17-37

Leave a Reply