about the writer

Mark Davis

Mark Davis is Dewitt Wallace Professor and Chair of Biology at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA.

Mark Davis

Like native species, some non-native species cause problems, some produce desirable effects, and most we do not think much about. When it comes to management, it is important that we worry about the right things. We should always worry about species that threaten human health, negatively affect the economy, and/or undermine ecological services. We should worry much less about species that are not producing any of these effects but are simply altering the composition of communities and other ecological processes. We should worry less about the latter species because we need to utilize the public’s limited management resources on the first group of species. Cities simply do not have the luxury to consider as harm mere ecological change.

It is important to remember that ‘harm’ or ‘damage’ is in the eye of the beholder. Normally, there is little disagreement over what constitutes a harmful species when the harm consists of threats to human health, the economy, and/or to ecological services. However, citizens may differ dramatically in how they view other non-native species. While a non-native plant may be viewed as harmful to a nativist simply because it is occupying space that could be occupied by a native plant, the same species may be viewed as desirable by an herbalist, and beautiful to someone else. Urban managers need to be careful not to assume that their view of such species is shared by all, or even a majority, of the public, i.e., those who are paying their salaries and funding their departments and agencies.

While we should worry about some non-native species, we need to remember that many non-native species are contributing positively to the environment and to the life of urban residents (human and non-human). For example, like native plants, non-native plants fix carbon, provide shade and reduce air temperatures, reduce erosion, provide habitat and food for native animals (including native pollinators), and many enhance the aesthetic experience of urban human residents. Since, in many instances, these species are growing in places where native plants do not thrive, eradicating the non-natives actually will compromise ecological services and quality of life of the human residents.

Without question, the traditional nativism approach to managing urban biodiversity has created obstacles to gaining widespread public support for the management of urban environments. While most of those schooled in conservation over the past several decades have been taught to prefer native over non-native species, simply on the grounds of their origins, many in the public have continued to take a much more nuanced approach to species, judging individual species on their actual effects and not on how long they have been here. Since many of these species have been in the city longer than any human currently alive, some of the non-native species actually contribute to the residents’ sense of place. A good example of this is the recent public backlash in San Francisco against a proposal to remove thousands of eucalyptus trees from a park and natural area. The wooded environment provided by these non-native trees had been highly valued by many area residents. If destroying a place they loved were not enough, the eradication methods were to involve large amounts of chemicals.

The public is getting smarter and less tolerant of the types of methods commonly used to eradicate and manage non-native species. Unless managers of urban environments abandon the simple-minded nativism approach, and begin following the public’s wisdom and start taking a more nuanced approach to species, they can expect to encounter an increase in public backlash in the future.

about the writer

Katie Holzer

Katie works with city managers to create urban natural areas that benefit both people and wildlife. She is a Ph.D. Candidate in Conservation Ecology at the Univ. of California-Davis.

Katie Holzer

What are major goals for urban natural areas, and how do invasive species management actions fit, or not fit, with them? In the face of continued urban growth worldwide and rapid climatic changes, one major goal for urban natural areas may be to create and maintain resilient, functional, and healthy ecosystems into the future, which may or may not be comprised entirely of native species. Another major goal for urban natural areas could be to provide a place for local residents to connect with and enjoy nature.

Cities house over 50% of the world’s human population, but take up less than 3% of the land surface. This demonstrates that cities may not be priority areas for conservation of rare native species, but they may be the most important place for many humans to develop an appreciation for, and connection with, nature. By understanding that they are part of nature, rather than removed from it, this can make people more likely to work to preserve it. If child in a city ventures out to a local pond to wade among the cattails and catch a frog, does she care more that there is a pond, cattails, and a frog that she can interact with, or that those species are native?

I think almost everyone can agree that it is important to isolate introduction pathways and vigilantly apply early detection and rapid response techniques to prevent introduction and spread of invasives in cities. It is of course also important to make sure that urban exotic species don’t become invasive outside of cities. But what about species that were introduced decades or centuries ago and are now well established in altered urban ecosystems? Control of established invasives is often more difficult in cities than elsewhere both because the landscape is more disturbed and because cities are a patchwork of management agencies, organizations, and private owners with differing goals, schedules, means, and methods. Consequently, particular invasive species are often controlled over small areas or short timeframes with low long-term success.

Attempts at invasive species management that don’t succeed in the long run may simply be a non-ideal use of limited resources, but there is also increasing evidence that many intensive management actions have the potential to directly or indirectly harm native species. This harm can occur for a number of reasons, many of which are more pronounced in urban areas. Invasive control actions can produce substantial short-term disturbances (e.g. mowing or chemical removal of large stands of plants) which have the potential to negatively impact native species in any landscape, and can be especially detrimental in small, isolated urban natural areas where native organisms may not have other suitable places to move to for refuge. Urban organisms are often already stressed by many other factors, making them less able to cope with a sudden loss of cover.

In addition to potential increased harm by control methods, it is possible that urban wildlife species are less in need of maintaining entirely native species composition. Most native wildlife species have not been able to persist in urban habitats, and the subset that do are often those able to rapidly adapt to novel ecosystems and make use of new habitats that they may not have experienced before. These relatively adaptable species are often more able to utilize introduced plants as habitat than species that do not occur in cities.

Due to the unique challenges, potential harms, and possible lessened necessity of some invasive management actions in cities, invasive species management may not always have a strong place in working towards the major goals of urban natural areas.

about the writer

Paula Villagra

Paula Villagra, PhD, is a Landscape Architect that researches the transactions between people and landscapes in environments affected by natural disturbances.

Paula Villagra and Carmen Silva

Our thoughts on this topic are influenced by our experience in landscape planning, design and ecology in the Chilean environment which lack of enough nurseries to produce native plants in the amount and standards needed for the development of urban landscape projects. Of course, we would prefer to design and plan parks and plazas with native plants only; however, the cultivation of native species and the knowledge about their management (e.g., water requirements in urban environments) and behavior (e.g., survival to municipalities’ management practices) is still limited (although developing fast!).

In this context, exotic plants are useful, because they are easily available, grow faster than many natives (at least faster than ours in Chile) and depict dramatic seasonal changes in terms of color and canopy density, which adds visual and temporal diversity to urban sites, making them attractive to people.

Nonetheless, including exotics in urban zones can be highly problematic if the selection and management is not taken care of. Exotic plants have higher water demands which on one hand is not sustainable, and on the other hand, if enough water is not provided, exotics take it from other plants, deteriorating the overall design and affecting mostly our natives (which do not have the standards to compete with them). Under extreme conditions, the exotic plants die faster, creating unattractive environment.

Other exotics usually used in urban sites in Chile (e.g., Acacia dealbata) can expand due to their invasive qualities and the ‘comfort’ they find in urban parks and plazas where water is provided regularly. Indeed, this kind of issue is usually ‘solved’ with environmentally toxic insecticides, diversifying the problem into the environment.

Besides, native plants commonly used in our cities increase health problems. Some (e.g., Platanus orientalis) cause severe allergies by the spread of seeds in the reproductive times of the year. While others (e.g., Melia azedarach), pollute the urban environment after the fruits fall and glue themselves to the pavement.

In terms of species interaction, the overuse of exotic plants has increased the presence of exotic over native fauna, altering urban “natural” systems. For example, exotic species are chosen due to their ornamental benefit (e.g., the fruit of the Cotoneaster sp.), which can be very attractive visually. However, they do not provide food for birds, which, as a result, leaves the urban environment resource-poor and require wildlife to search for other sites with better survival advantages.

All together, the problem of introducing exotic plants in urban sites affects ecological aspects, visual landscape qualities, and human well-being. In addition, it can cause a deep misunderstanding among the public, influencing human behaviors and the developing of environmentally unfriendly urban practices. In terms of the private landscaping developed by the general public, most people copy from public parks and plazas what they like and see. Hence, to overcrowd the public areas with exotics plants can convey urban dwellers the wrong message. If that is the case, people will introduce exotics into their private gardens (or increase the amount they have), which in turn, can intensify the problems exposed before, developing a local culture unaware about the role of native plants and their ecological and social values in urban sites.

We do not disagree with using exotics in the design and planning of urban environments when other options are not available; however, in our experience, the selection of exotic plants, the amount which they are introduced, and their distribution should be carefully studied by experienced professionals in landscape and urban ecology. Good results can be achieved when natives already on site are included in the landscape design, when exotics are chosen due to their aesthetic as well as ecological values, and when the community is involved during the process of design.

[second_bio]about the writer

Carmen Silva

Carmen Paz Silva is a PhD student at Universidad Austral de Chile and is particularly interested in the effects of urbanization on biodiversity.

about the writer

Timon McPhearson

Dr. Timon McPhearson works with designers, planners, and local government to foster sustainable, resilient and just cities. He is Associate Professor of Urban Ecology and Director of the Urban Systems Lab at The New School and Research Fellow at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies and Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Timon McPhearson

Exotic invasive species are damaging but here to stay

We should worry. Urban exotics species often have negative ecological and economic impacts and understanding the complex interactions among simultaneous exotic effects and feedbacks is ecologically very challenging. Let New York serve as a case study since it is one of the most “infested” states in the U.S.

Forests across New York State, including urban forests, are filled with exotic earthworms. Exotic earthworms have slowly re-invaded these forests since the last glaciation, first arriving with European settlers in the balls of soil around plants and soil used for ballast in ships. The earthworm invasion hasn’t stopped, if anything it is probably accelerating. For example, when people buy worms for their urban compost bins they buy exotic worms, and these get out and spread to local backyards and forests. Now there are about 45 species of exotic earthworm species in the New York region.

So what? For starters, exotic earthworms change nutrient dynamics and thereby alter the community structure and species assemblages of forests. Most forests have a layer of decomposed material (duff) that was laid down over thousands of years through the accumulation of deciduous trees dropping their leaves in the fall. Duff protects soil from erosion and provides critical habitat for many native species (ferns, wildflowers, salamanders). Earthworms chew through this later, aerating it, releasing carbon (a greenhouse gas), adding nitrogen, and thereby changing soil chemistry. This can completely alter forest diversity, structure, function, and may affect the provisioning of urban ecosystem services.

Indeed, scientific studies are showing that native plant species grow better when there aren’t any worms. Not only that, where exotic earthworms have invaded, so do other exotics, like Japanese barberry and Asiatic bittersweet, both invasive plants that are damaging forest diversity. So, exotic invasives not only can have direct negative ecological impacts, they can also create the conditions for further invasion by other exotics. How many simultaneous and interacting exotics can our natural areas handle before they shift into complete different system states or even collapse?

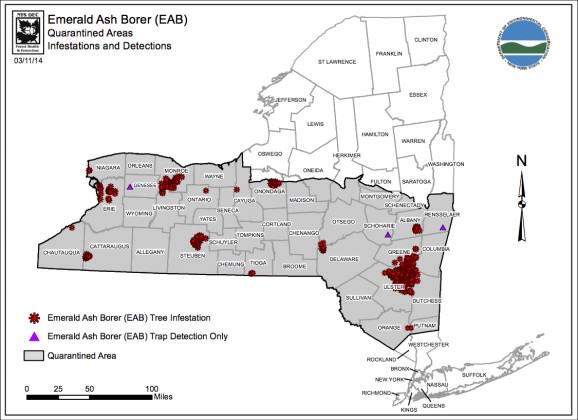

New York City (NYC) is an epicenter for invasive species in the U.S. and functions as a major pathway for invasive species to the rest of the continent. One of the challenges we have in managing urban ecosystems is dealing with the wide variety of exotics, including their ecological interactions and feedbacks. Natural resource managers in the NYC region have to worry about Asian longhorn beetle, Emerald ash borer, Hemlock wooly adelgid, and many other insects pests, in additional to a wide range of aquatic (zebra mussels, water chestnut) and terrestrial (kudzu vines) exotic invasives. Chestnut blight wiped out American chestnut populations — more than 9 million acres of American chestnut forest from Mississippi to Maine. Ash trees, which are common in towns and cities, as well as in backyards of homeowners, are likely to experience the same fate from the Emerald ash borer (EAB). This beetle has killed 50 million ash trees in Michigan alone since 2002 and it is closing in on New York City. Unlike chestnut blight, EAB will probably end up killing off 20 different species of ash trees. As Ash trees start dying, removing the dead trees before they fall and cause property and other damage will be financially costly for municipalities and homeowners. The USDA Forest Service has estimated the emerald ash borer will cost communities in a 25-state area as much as $10.7 billion by 2020. In New York City, forested areas include 900 million ash trees, approximately 10% of the total NYC urban forest.

New York City (NYC) is an epicenter for invasive species in the U.S. and functions as a major pathway for invasive species to the rest of the continent. One of the challenges we have in managing urban ecosystems is dealing with the wide variety of exotics, including their ecological interactions and feedbacks. Natural resource managers in the NYC region have to worry about Asian longhorn beetle, Emerald ash borer, Hemlock wooly adelgid, and many other insects pests, in additional to a wide range of aquatic (zebra mussels, water chestnut) and terrestrial (kudzu vines) exotic invasives. Chestnut blight wiped out American chestnut populations — more than 9 million acres of American chestnut forest from Mississippi to Maine. Ash trees, which are common in towns and cities, as well as in backyards of homeowners, are likely to experience the same fate from the Emerald ash borer (EAB). This beetle has killed 50 million ash trees in Michigan alone since 2002 and it is closing in on New York City. Unlike chestnut blight, EAB will probably end up killing off 20 different species of ash trees. As Ash trees start dying, removing the dead trees before they fall and cause property and other damage will be financially costly for municipalities and homeowners. The USDA Forest Service has estimated the emerald ash borer will cost communities in a 25-state area as much as $10.7 billion by 2020. In New York City, forested areas include 900 million ash trees, approximately 10% of the total NYC urban forest.

Map of outbreaks of Emerald ash borer across New York State. New York City is under quarantine to prevent infestation of the urban forest. (Source: NY Department of Environmental Conservation)

The impending decline of ash trees, is just one of a very long list of major ecological and economic effects of invasive exotic species. In urban areas like NYC, where we are trying to promote natural areas that both preserve native biodiversity and provide important ecosystem services for urban residents, invasives pose a difficult management challenge since multiple interacting species are already well established. Realistically though, we have probably already lost the battle over exotic invasives and need to begin turning our attention toward adaptation. Like climate change, exotic species are here to stay, and we need to spend some portion of the money spend to control invasives to develop innovative ways to harness their rapid growth, fast reproduction, and competitive ability for green infrastructure solutions to pressing urban challenges. For example, we may find from stormwater absorption, flood control, and air pollution to carbon removal and urban cooling, that some exotics are more effective than native species. Comparative scientific studies in cooperation with local management could go a long way towards improving our understanding of the potential benefits of exotics and how they can be employed to meet sustainability and resilience goals.

about the writer

Ana Faggi

Ana Faggi graduated in agricultural engineering, and has a Ph.D. in Forest Science, she is currently Dean of the Engineer Faculty (Flores University, Argentina). Her main research interests are in Urban Ecology and Ecological Restoration.

Ana Faggi

How much should we worry about exotic species in urban zones?

Urban habitats are more or less intense modifications of the original matrix and native plants are often either eradicated or replaced with exotic ornamentals, since the structure of the city is heavily influenced by the cultural tastes of society and its fashions.

Urban green is in many cities a necessary component to improve the microclimatic conditions and make cities more livable. In Argentina, the urban forest in towns located in arid or semiarid zones are almost entirely composed of exotic trees such as blackberry, poplar, ash, etc. In such cases, there is no real chance of having an urban forest composed only by native woodland.

As cities extend across the rural landscape, they bring about the fragmentation of biotopes, thus creating novel habitats for alien organisms. Nevertheless, a certain degree of “naturalness” can be found in the riverine vegetation along watercourses, although natives species coexist with exotic trees and shrubs. This vegetation has important benefits for human welfare. In my opinion, the positive of promoting native species is that people can become familiar with them. Exotics, provided they are not invasive, are welcome, taking in account that they are very much appreciated.

How do we reduce damage from exotic invasives when management resources are limited?

Here it would be necessary to involve the local community in eradication programs. Students of forestry, agronomy and environmental science could lead projects involving other volunteers of all ages. These actions are ideal opportunities for the local community to connect more deeply with nature working together towards a common goal. Simultaneously they would allow people to understand the relationships between cultural and ecological processes.

Are there conflicts between management or eradication efforts and building general support for urban biodiversity?

Ordinary people do not see differences between exotic and native species at all! Generally they do not understand why the exotics should be eradicated. Therefore, exotic management in the city needs to be well communicated to the public, explaining with concrete examples the grim consequences of invasions in the local ecosystem.

about the writer

Deborah Lev

Deborah Lev is about to retire from the position of City Nature Manager for Portland Parks & Recreation in Portland, Oregon, overseeing natural area management, environmental education, urban forestry, and community gardens.

Deborah Lev

As an increasing percentage of the world’s population lives in cities, biodiversity becomes more an urban issue. In recent decades, authors have expressed surprise and delight at the discovery of urban biodiversity hot spots. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised. Throughout history, people have gathered and established settlements in locations where we would expect biological diversity: the confluence of rivers, along estuaries, and at geographic transitions such as mountains to plains. Over these same few decades, we have seen an expansion of the world’s cities and an attendant expansion of invasive species.

It is not a surprise that high concentrations of people beget high concentrations of invasive exotic species; managing urban natural areas, it is apparent that invasive species are the primary threat to remaining habitat patches. Most of the terrestrial plant invaders that threaten our natural areas were brought to the region intentionally by people as garden ornamentals or land reclamation projects. People also serve as unintentional vectors of invasive species. Naturalized invaders from adjacent gardens and compost piles threaten our urban natural areas while hikers, bikers and their pets inadvertently spread seeds along park roads and trails.

People, of course, can be part of the ongoing management of these species as well. Inviting community stewardship of our natural lands is a tremendous opportunity to introduce people to nature and build an appreciation for natural systems, ecosystem services, and the value of biodiversity. Raising the awareness of invasive species in the urban population is necessary to combat these pests on private lands as well as public spaces. Community volunteer stewardship can also become a valuable tool in the resource constrained efforts to control invasives. Our integrated pest management system includes hand pulling of weeds by volunteers as well as use of herbicides by state-licensed staff and contracted crews. We deploy volunteers on sites where we will continue to invest in maintaining the improved conditions. Often, volunteer hand-pulling of vines and ground cover weeds is paired with the work of professionals to remove invasive trees or apply chemical herbicides where required.

Another way to manage scarce resources in the invasive species battle is to prioritize where to fight. Portland Parks & Recreation (PP&R) manages more than 8,000 acres (> 3000 ha) for habitat. A matrix of sites with axes of ecological health and ecological function potential dictates where resources are deployed. In general, we focus on maintaining the ecological health of sites already in good condition and improving the health of sites where ecological function can be achieved by combatting the invasive species. Other factors considered in setting work priorities include connectivity to other sites and community support, especially from an organized friends group willing to assist in management activities.

As a local government land manager we directly treat terrestrial plant invaders. We are also well aware of the key role that urban areas play in the migration of other critical invasive species. One example: international cargo ships, potentially harboring invasive species, call at coastal ports, primarily in urban areas. Entomologists predict that the Asian long-horned beetle is likely to appear in Portland via cargo ship. We are training park staff and volunteer partners to recognize this insect and its characteristic damage to trees. The preferred target species for these insects are maple trees which comprise 40% of Portland’s street trees and 60% of the trees in Forest Park, at 5200 acres (2100 ha), our largest City natural area. Portland is a likely entry spot for the continent — just one example of a potential threat in one port city.

Peter Werner

First of all, I have to state that I know more about plants than animals and that I have an European bias.

My answer for the first question is rather clear. We should not be worried about exotic species in urban areas! Some species are pests or cause diseases, but that is not only true for exotic, also for native species (e. g. rats, allergic potential of hazelnut). Exotic species and urban areas — these belong together. Why?

Cities are centers for political power, money, culture, ideas, goods, and so on. Therefore, they are locations of exchange and accumulation. They are market places, connected with the world, and that includes goods, which come from outside. Introduction of nearly everything is an inevitable feature of cities. It is estimated that around 16,000 ornamental plant species were brought to European cities from all over the world (Dehnen-Schmutz et al. 2007).

Urban areas are also places where strange, foreign persons, ideas, and things can exist, rather than outside of cities. The German phrase “urban airs makes you free” underlines it, describing a principle of law in the Middle Age. That includes the idea that exotics are not dangerous per se, but they are an enrichment for the society. Many humans become scared of the otherness.

In my mind you can transfer that picture to plants and animals, too. That means, as I mentioned above, you cannot imagine a livable, busy city in which exotics, including plants and animals, do not play an important role.

As you look to the fact, then you can see the following. Native species represent the majority of species in cities, more than exotics, and this is valid for birds and plants (see publication of Aronson et al. 2014, a working group which analyzed more than 100 cities worldwide). Common native species are still the dominant species in European cities, and that is also true for the inner urban areas. With respect to the species richness, the exotics enrich the fauna and flora in urban areas and compensate the lost of native species. The number of flowering plants, especially of the ornamental plants, and their blossom time over the year are increased in cities, and a lot of insects, notably pollinators, benefit from them.

Some species, for example the goldenrod (Solidago gigantea) in German cause problems in natural and semi-natural areas, but not in cities. Many people like the goldenrod as an ornamental plant in their gardens or gather it from wasteland, as I see it in my neighborhood, to bring it at home for a bunch of flowers. A problem can be that such exotic plants spread out from gardens to the outside, like fashion, which spread out from cities to rural areas, impacting cultural and natural landscapes.

about the writer

Glenn Stewart

Glenn Stewart is Professor of Urban Ecology, Lincoln University, NZ. Current research is on Southern Hemisphere urban ecosystems and invasive species, successional processes and predicted changes in global climate.

Glenn Stewart

These are my views from the colonies of Empire downunder. Here I am including South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Although some of these thoughts and issues probably relate to North America as well. To put my views in context you need to know a quick bit of history here. The British Empire (god bless their soul) carried all things familiar to them to the colonies (to make them “feel at home”). And they took “exotic” plants and animals from the colonies back to mother England (but that is another story for another time). So in New Zealand for example we have many species of plants and animals that “do not belong”. Add to this the fact that the native flora and fauna evolved over millions of years in the absence of mammal browsing and in the absence of mammalian predators. That is why we have flightless birds and strange and wonderful ancient plants! At least 85% of all native plants, birds, frogs, and reptiles found in NZ are endemic to NZ. That is why we are one of the 25 global biodiversity “hotspots”. So what is the situation now after 800 years of Polynesian settlement and 150 or so years of occupation by Europeans? Here is a quick summary (numbers approximate):

2300 species of native plants, 2700 species of naturalised exotic plants (that reproduce and are invading), 33 species of naturalised mammals (the only terrestrial mammals prior to human settlement were 3 species of bats), and countless species of exotic birds. We also have on the order of 30,000 to 40,000 species of exotic plants in cultivation. And one of these species becomes naturalised every 3 months! That’s why NZ has such a stringent border control program!

So what does this mean for urban environments in New Zealand? Basically it means that our cities are dominated by exotic plants and animals — cultivated gardens of exotic species, lawns dominated by Northern hemisphere grasses, woodlands constituted of species from around the globe, urban birds from every continent on the planet and mammals from the European hedgehog to the Norway rat!!! And many of these mammals are predating our native birds and invertebrates. So one of the biggest challenges we face is to reduce the “exotic” influences and enhance and restore indigenous nature. Hence a real focus in the last 20 years or so on restoring native plant communities, and associated bird life. It is an enormous challenge!!

So the removal/reduction of exotic animal and plant species are one of the foremost issues that challenge us in restoring indigenous biodiversity in our cities. And also in restoring vital ecological services to enhance sustainable ecosystems.

about the writer

David Burg

David Burg has been working on the environmental issues of New York and other metropolitan regions for over thirty years. He first started working as a naturalist in 1966, as a field assistant for the Department of Ornithology at Yale University. He subsequently worked odd jobs while hitch-hiking around North America, Central America, and Europe before resuming his naturalist career in New England and Israel.

David Burg

The real Invasive Worm in the Big Apple

Like most mega cities, New York has worlds within worlds. There are the well known human divisions of class and culture; most of us know that even if we live on the edge of an outer borough we can hop on a bus to a subway and travel from neighborhoods of chitlins and greens to Kosher Bukharian lamb, of Sichuan soup dumplings or gnocci Bolognese. But there is another New York.

Visit Breezy Point Queens in mid-winter and snow buntings swirl with real snow while white gannets dive for fish offshore. Almost every year a snowy owl roosts by day on the white dunes and watches the white breakers curl over the green waves. Or visit Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx in summer when the Great Granny Oak stretches her ancient limbs towards the Golden Meadow where goldenrod flowers are visited by clouds of butterflies and shiny green native bees. Prairie grasses nod in the wind next to little white orchid blossoms, all a three minute walk from the egrets feeding in the high marsh of Long Island Sound. In the blue dusk a great horned owl lands in the old oak and hoots softly while the fire flies twinkle below. Yes, there is real nature in cities, and it is good. Yes, we should be very afraid, very afraid of invasive species that wipe out our remnants of ancient ecosystems.

Even in the most highly built sections of cities wild nature persists. Native cherry trees and daisy flea bane flowers duke it out with invasive ailanthus trees in abandoned vacant lots. Peregrine falcons and red-tailed hawks breed on the cliff-like walls of the concrete canyons. We can do much more to encourage nature in the cities but we need to start by understanding and protecting what we still have.

Because big cites are global transit hubs they are often epicenters for invasive species, as they are for new diseases of humans. The cities are where the wooden boats brought in the first farm weeds from Europe, and where containerized cargo ships now bring in insects pests like Asian long-horned beetles that have stowed away in wooden packing crates. Cities are where jet liners bring in people with HIV and ebola and West Nile Virus. Preventing new invasions of pathogens should be a much higher priority than it has been. Ounce of prevention vs. pound of cure is trite but true.

On the other hand, when it comes to the expense of dealing with invasive plant control cities and suburbs have a built in advantage. A surprising number of our millions of residents are willing to volunteer their time to keep the parks and green spaces they love weed free. In more than thirty years of working to protect nature in cities there has been nothing more gratifying to me than the last twelve years of hands-on work to remove the few rampant invasive species that pose a threat. The Earth Tenders program of WildMetro has organized invasive control events to protect native diversity with a terrific diversity of humans. Everyone from an hundred bank employees doing community service to small numbers of inner city youth have helped. As in many such programs in cities around the world, people from eight to eighty are happy to get involved. Great exercise, great comaraderie — a classic case of doing well while doing good.

And except for a couple of times when we accepted some gloves and hand tools, we cost the city nothing. We use no power tools, no chemicals and we plant nothing. No need to. In site after site one sees that given a whiff of a chance even delicate species like wild roses come roaring back. Such conservative and cheap management of nature has a long history, and it is just common sense. While we were working in our quiet, patient, labor intensive way we were surprised to learn of the Bradley Method. This is a nearly identical approach developed by two sisters in Australia. We have not used any conservation grazing yet, but around the world, and even in New York City, goats and other animals are being carefully used to control weeds. Volunteers and other animals are the sensible, and affordable way to tackle the weed problem.

Sadly, these simple methods are not popular now with most government or non-profit agencies. Currently favored means of nature management and invasives control may indeed jeopardize public support for nature protection. Right now in New York City and much of the rest of the United States, the standard way of handling weeds is to use a variety of harmful options. So many government agencies now use what I call the 4Ps approach. They use Plowing, Plastic mulch, or Poison, then they Plant. These are modern industrial techniques at work. No thought of using careful slow hand work to nurture and protect the last of our ancient lineages of native species with their unique genetic heritage. We have had to overcome obstacles to just get permission to volunteer in parks, even though our results have been outstanding.

There are two really troubling aspects to current methods. The first is that tons of herbicides being supplied. New evidence continues to emerge about the dangers of even “safe” poisons like Round Up, one of the most commonly used formulations. Yes, the same chemical Monsanto developed to spray on genetically modified corn just went off patent and various formulations are now widely used in natural areas. And in addition to the harm they do in the environment, there is risk in the manufacture, storage, transportation and handling of any toxic substance. I recently learned that several government agencies in the city have been using Oust, a poison that is designed to kill all plants and seeds even before they emerge in the spring. Though some chemicals can be carefully painted on cut stems, I have recently seen the city using broad cast spraying of these poisons. This kills indiscriminately. Both the target species and the last native plants are eliminated.

But never fear, the agencies have a solution to the scorched earth policies they use. Giving the lie to the affordability argument, New York City alone is spending hundreds of millions of dollars to come in and plant trees. This is the second troubling aspect of current vegetation control. The trees they plant cost an average of $1400 a piece. They are a mix of native and non native, but few are raised from local seed. What is so insane about this is that even on vacant lots it takes work to keep trees from coming in on their own. Each tree can produce hundreds of thousands of seed a year. Many are carried by wind and birds. Planting trees in an abandoned lawn or meadow is a case of carrying coals to Newcastle. It is only a matter of time before citizens get outraged at this harmful waste. I only hope they do not turn against all urban nature protection in reaction.

Invasives are not the only threat to urban green spaces. For several years now New York and other cities have developed a mania for paved asphalt recreation roads for bicycles, roller blades and other devices with wheels. I love bikes, but these are often placed in the last green spaces. One such road (to add insult to injury they are often called Greenways) that was built on Staten Island went right through a patch of rare plants. Another one planned for Pelham Bay may be about to go right through a patch of rare iris and native sunflowers. And any large green space, especially near waterfront or low income neighborhoods, is fair game for housing development, sports stadiums, new highways and recently new gas pipelines. The impact of invasives on our last bits of urban nature is only one of many threats that are working together to unravel our green blanket. These weeds are, however, one of the more controllable problems. In cities we still have the opportunity to reweave the blanket, if we only have the will. The real worm in the Big Apple is not an invasive plant or animal species. It is greedy and ignorant people.

about the writer

Pippin Anderson

Pippin Anderson, a lecturer at the University of Cape Town, is an African urban ecologist who enjoys the untidiness of cities where society and nature must thrive together. FULL BIO

Pippin Anderson

Invasive alien plants in the City of Cape Town present a real conundrum. The City is heavily invaded, most significantly by Australian species, in particular Acacias and Eucalypts. These species were actively introduced for various reasons and have since run rampant, with huge losses in indigenous biodiversity, much of which is endemic. They use more water than indigenous flora with hydrological losses of a scale worthy of attention. As species from a similar fire-driven system, they are favoured by the fires that sustain the Cape Flora, but their much higher fuel loads serve to alter fire regimes and create hotter and longer fires, to the detriment of the local flora. So at a glance it seems like a clear case where the call for the eradication of these alien invasive species is imperative and without question the right thing to do.

However, the original reasons for their introduction in some cases still hold. For example Acacia cyclops and Acacia saligna were introduced to stabilize mobile dune systems across the Cape Flats. While obviously it would be ideal to have pristine, and indeed mobile, dune systems, the truth is that now these areas are heavily inhabited, largely by the City’s poor, and if these dunes started to move once again it would present a massive management problem. The indigenous flora of the Cape is typically shrub dominated, with few trees. In light of this, large stands of woody invasive aliens are a source of wood, used both for energy provision and as a livelihoods supplement by the urban poor who gather wood and sell it by the side of the road. A further complicated benefit is in the government public works schemes, such as Working for Water, which employs the indigent to clear invasive aliens to improve water gains.

So where does that leave us? I certainly feel the problem needs to be contained, and that there should be no further loss in biodiversity to invasive aliens. But in the case of Cape Town, the plight of the poor is no trifling matter and associated benefits of these emergent novel ecosystems have to be taken in to consideration. So, I would put my money behind biological control. Biological control requires that some of the original population of any invasive species remains to serve as host population to the control agent, but sees the invasive species contained. Much research is needed in this area, so that would be an area of critical importance. An additional spin off might be an associated public works scheme with the poor employed in control distribution, the clearing of die off, and the cultivation of control agents for distribution.

So it seems to me to be a problem that does not present an either-or answer, but rather one that requires a middle-road.

about the writer

Toby Query

Toby Query is a father, husband, and ecologist. As part of the City of Portland’s Revegetation Program since 1999, he stewards natural areas for all Portlanders. He founded the discussion group Portland Ecologists Unite! which created spaces to learn, discuss, and connect over ecological issues.

Toby Query

As a manager of natural areas for the City of Portland, Oregon for the past 15 years, I have slowly shifted my thinking from one that “combats evil invasives” to a more nuanced approach. This approach targets thresholds and moves the system to a healthier state with the lowest overall impact. Interventions to restore habitat need to better evaluate the impact on the ecosystem as a whole.

In the past our crews cut down invasive Armenian blackberry (Rubus bifrons) around our planted seedlings in the middle of bird nesting season. We destroyed the occasional nest in blackberry bushes, but didn’t realize that many were “species of concern” including the little willow flycatcher (Empidonax traillii brewsteri). In 2006, another City of Portland initiative, the Terrestrial Ecology Enhancement Strategy, published documents demonstrating how to avoid damage to nesting birds. These documents, along with discussions with wildlife biologists, led us to shift our treatments to avoid the bird breeding season along with goals to reinstate lost structure and function for target species.

Each invasive species should be evaluated for its current and projected impact to the system, how well it is established, and if its presence is a sign of a degraded system or it is the cause of a community shift. In my experience, established invasive species will resist eradication even with the best orchestrated attempts unless they are detected early on. Thus, we should shift resources towards prevention of new arrivals and start to embrace some of our invasive species.

An example of this involves the much-reviled Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense). It occurs on most restoration sites that we manage, but how much damage is it doing, and can we effectively replace it? Canada thistle arrived in North America in the 1600’s and other species have been coevolving with it ever since. The seeds are an excellent food source for goldfinches, and the plant and nectar are valuable habitat for many native bees and butterflies. With this knowledge, ecologists, including myself, are starting to accept it, putting value on its services for our regions’ wildlife.

Our “love to hate” invasives mantra has led us urban restoration practitioners to potentially harm wildlife in our quest for eradication and control. Restoration performance success often involves meeting a minimum threshold of invasive plant species cover percentage. This needs to be re-evaluated, especially in an urban context, and instead use goals and objectives involving habitat structure and function. By choosing focal species’ preferred habitat (i.e. dense patches of shrubs for the flycatcher) or desired functions (like shading a stream), we will have a clearer path forward without jeopardizing what we seek to improve.

We need to do more evaluation of the causes of the stress to the system and fix those, rather than address the symptoms of a disturbed habitat (which can be expressed through the abundance of invasive plant species). Some of these fixes are outside the ecologist’s hands, such as nitrogen deposition and hydrological changes, but we can work to advocate for these solutions. This approach can save resources as well as build public support. When we frame our work as land managers as a war against invasives, rather than well thought out plans to improve ecological health, we have the potential of making simple decisions that don’t solve the problem. When evaluating an invasive species, we need to involve ornithologists, herpetologists, entomologists and others to more accurately assess what the effects of the “war” might be on the system as a whole. We need a more complex dialogue to reflect the challenges that we face as ecologists and continue to seek new pathways to enhance our urban wildlife habitat.

about the writer

Madhusudan Katti

Madhusudan is the Director of Science, Technology, and Society, and Associate Professor of Public Science in the Department of Integrative Humanities and Social Sciences at North Carolina State University.

Madhusudan Katti

Reconciling native and non-native species in urban biodiversity

Humans are the most invasive species on Earth. Our cities, ecosystems we build and replicate around the world, are also focal points from which other species have invaded native habitats. Just as wanderlust defines our species, so does the biophilia which makes us take living elements of our habitats with us wherever we go. Carrying a suite of species as sources of food, comfort, companionship, and beauty, has always been part of our cultural and evolutionary baggage. Invasiveness is something evolution tends to reward, and our own evolutionary success springs from a certain restless invasiveness.

We have spent millennia figuring out how to make some species grow where and when we want them. Meanwhile, other species have latched on to our coattails making the most of this new mode of hyper-efficient long-range dispersal: the hairless ape that travels the world, with baggage. Only recently have we realized the often devastating consequences of bringing exotic species into native habitats. Invasive species fuel some of the most intense debates among conservationists, often laden with hysterical rhetoric about alien, exotic, invaders who must be exterminated. Yet we tiptoe around the fact that we are the most invasive, disruptive species on Earth.

Cities are where most humans now live, where we often first introduce new species, and whence some of these species launch invasions into new habitats. Indeed, cities themselves seem like invasive habitats proliferating in and destabilizing ecosystems around the world. Cities must therefore be central to our efforts to address the challenge of invasive species. Cities embody the contradiction between our desire to control nature, shaping entire ecosystems to suit our purposes, and our growing desire to conserve nature and biodiversity.

How do we reconcile our innate desire to build habitats for our own biological and cultural needs with a growing awareness that perhaps we should leave nature alone? It must start with owning our central role in this ecological conundrum. It requires us to transform our role beyond the dichotomy of active perpetrator / passive bystander in the drama of invasive species. We must embrace the role of more deliberate stewards of the lands we now dominate.

As more people recognize the problems of invasive species, many now seek ways to build native species friendly urban landscapes. Ecologists are good at understanding the effects of non-native species in native habitats, and in raising the alarm about invasive species. We haven’t done enough to actually transform the practices that contribute to the invasive species problem. Urban ecologists have been lax in engaging with one group who arguably wield the greatest influence on this challenge: gardeners, nurseries, and landscapers. The growing desire to make urban gardens native-friendly is constrained by lack of available species options in local nurseries, and of expertise in nurturing native species. Ecologists must fill this knowledge gap by developing better ways to support native species in urban habitats in partnership with the people who actively transform the landscape.

Forget “leave nature alone”; in cities we must become better ecosystem engineers, designing habitats more consciously to enhance native biodiversity while limiting opportunities for non-native species. We must also recognize that some non-native species have become naturalized to play important roles in their adoptive ecosystems, so simply eradicating them is not the ideal solution. People move and grow plants and animals to fulfill complex social, cultural, aesthetic, and emotional needs. We must develop a broader vision of biodiversity that includes both the ecological roles of species and their cultural resonance for people. Balancing these will be key to managing invasive species in and around urban landscapes.

about the writer

Matt Palmer

Matt Palmer is a senior lecturer in the department of Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology at Columbia University. His research interests are primarily in plant community ecology, with emphases on conservation, restoration and ecosystem function.

Matt Palmer

Some exotic species are certainly causing problems in cities. In patches of remnant native vegetation, invasive exotics may be the primary threat to preserving native biodiversity. Those native species are important not just for the services they provide (e.g., habitat for wildlife, stormwater management, aesthetics), but also for the role they can play in connecting people to the nature of a specific place. In cases like this, managing invasive exotics — while almost always difficult — is probably a fight worth fighting.

For example, the Thain Family Forest in the New York Botanical Garden is a 16 ha old-growth forest in New York City. It is one of the few places that one can experience the landscape that once covered most of the city. There are several invasive exotic species present that displace native species. Staff from the Garden manage the forest quite intensively — including removing exotic species and planting native species — in an effort to maintain the forest in its historic condition. Urban restoration efforts like these may require so much effort that they essentially become gardening, but if the end goal is the preservation of indigenous species in their historical landscapes then intensive management may be the only way to succeed.

This being said, cities are full of wild or semi-wild areas that bear little resemblance to their historic condition. The environment has very likely changed with altered microclimate, hydrology, soil composition, and other factors. The kinds of disturbances and their frequency and intensity have likely changed — fires, floods, trampling, and pest outbreaks all have different dynamics in an urban matrix. And the plants, animals, and microbes that live in these areas are almost certainly different than those that were there before the city arrived. There’s a distinct set of cosmopolitan urban species — the “weeds” and “pests” familiar all over the world.

These weeds and pests — the classification of which is subjective — provide services that are generally undervalued. Exotic species in highly disturbed sites may be most of the biomass, which means those are the species doing the “greening”. For example, if the primary services provided by vegetation on a vacant lot are capturing some stormwater, cooling the air through evapotranspiration, and providing some habitat for insects and birds, these functions can be accomplished by both native and exotic species.

Some might argue that the urban ecosystem services provided by exotic species are less than those provided by native species. This may be correct, though I don’t think there is much convincing data on this question. However, it’s not really appropriate to compare the services from exotic species (which are often abundant in cities) with the services that could be provided by native species if they were present. If the native species are absent, rare, or declining, it generally consumes a lot of resources to manage them in a way that maintains their abundance. Those kinds of management require long-term investments of resources and face many practical challenges. There’s a much lower investment required to increase whatever services are desired from the species already present without worrying too much about which are native or exotic. It’s easier to tweak the system with the species you already have than to try to rebuild some historic system.

Cities are heterogeneous places. In almost every city, there are habitats that should be managed to maintain their indigenous species. But every city also has the neglected green spaces — often populated with exotic species — and these could be managed wisely with a more inclusive view of urban nature.

Leave a Reply