California has long been a center of gardening culture. With a mild climate and a history of agricultural expansion followed by rapid urbanization, California’s ornamental gardens are populated by plant species and cultivars imported from all over the world. Many of these exotic species have become iconic, such as the palm trees, figs, and citrus of southern California. However, the current drought has brought wide recognition of the fact that most of these ornamental plants, from the palm trees of Rodeo Drive to Santa Barbara’s landmark Moreton Bay Fig, are supported by irrigation that is rapidly becoming a scarce commodity. So, is there a place for ornamental gardens in the new California? We’ve been studying this question for a number of years in Los Angeles and its surrounding municipalities, and fortunately, the answers are not as alarming as most people seem to assume.

Water conservation in irrigated gardens generally has three components: watering less; employing more efficient irrigation technologies; and changing the composition of garden plants (by removing lawns and non-waterwise species, for example). Many Californians have concerns about the costs of these measures and their implications for the aesthetic and recreational quality of urban parks and gardens. Just as “xeriscaping” became associated with mental images of sparsely planted cacti and succulents that were unappealing to most people, the new language of water conservation is “mandatory watering restrictions,” which brings to mind brown lawns and withered flowers. Is that the future of California’s cities?

We’ve extensively measured the water use of residential yards, parks, and also individual plants and trees grown in the Los Angeles area, and can consider each of these measures in turn. First, let’s think about irrigation efficiency. Reducing water applications without changes in technology or plantings is the “low hanging fruit” of outdoor water conservation, but most people are lacking information about the actual water requirements of urban landscapes. Excess irrigation is apparent virtually everywhere in California, perhaps most visibly in urban storm sewers and storm drains. As the name implies, storm sewers are meant to convey stormwater—that is, rainwater—away from streets and residences. However, looking at California’s storm drainage system at any given time of the year, including the “dry season”, one will find storm gutters and sewers full of running water. In the absence of storm events, most of this year-round “nuisance flow” originates from irrigation runoff. Excessive irrigation has been prevalent in most California cities for a number of years, and the consequences have been severe not only for water conservation, but also for water quality: irrigation runoff contains contaminants that pose serious problems in coastal waters due to eutrophication and bacterial outbreaks. To combat this issue, some coastal municipalities prohibit excessive runoff from residential properties, but these restrictions are very difficult to enforce. Widespread over-watering has simply become an accepted source of both water consumption and non-point source pollution throughout the irrigated western U.S.

The potential upside to all this over-watering is that eliminating it can be an effective means of meeting conservation targets without drastic changes to landscaping. But, how will residents know how much to water? Many water districts and state and local agencies provide guidelines, although we have found that these often over-estimate the actual water requirements of urban landscapes, particularly lawns shaded by trees or buildings. Online recommendations and calculators are a starting point, but many residents don’t access or properly implement them. This is where irrigation technology provides the next effective strategy in urban water conservation. Most people have a general sense that lawn and garden watering requirements vary with the weather: cooler temperatures = lower water requirements. Unfortunately, the ubiquitous irrigation timers found in most California homes have to be adjusted by hand to account for changes in the weather. And even with the best of intentions, most of us have probably failed to adjust or shut off these systems during foggy or rainy conditions. Newer systems use environmental measurements to do this for us: there are systems that record soil moisture onsite or that tap into California’s network of weather stations to automatically adjust irrigation schedules at the appropriate times, although the accuracy of the calibrations for these systems can vary. Of course, changing irrigation technology costs money, and the reality is that these new systems need to be widely incentivized by water districts to be implemented on a large scale. The good news is that they work: for example, we found that a soil moisture-based system tested in residential turfgrass at the South Coast Research and Extension Center in Irvine, CA had almost 100% irrigation efficiency, with virtually no water lost to runoff or drainage (percolation below the rooting zone).

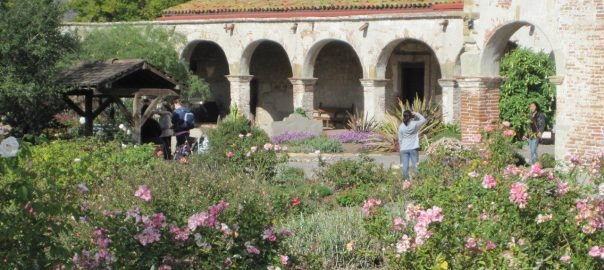

Lawn watering practices and the extent of turfgrass in California cities are important aspects of urban water conservation. We agree that reducing the area of urban lawns should be an important aspect of water conservation strategies. Yet much of the appeal of California’s urban gardens is due to their stunning array of other types of ornamental plants. Many media reports highlight fears about the loss of valued ornamentals such as exotic trees, heirloom roses, and other flowering shrubs as a consequence of the current drought.

Is there a place for these species in the new California? Most definitely, the answer is yes. Of all of the plants that we’ve studied, lawns require the most water by a large margin, mainly because they are very shallowly rooted. In all ecosystems including cities, the deep soil is a storage pool of water, and plants that are deeply rooted have a far better capacity to withstand drought than lawns and grasses. Virtually all shrubs and trees, including ornamentals, use far less water than lawns, and can persist on infrequent (but deep) watering if they’ve developed adequate root systems. One significant factor limiting the success of these species is that most home irrigation systems are optimized to keep lawns green, not to properly water trees and shrubs. Further, some urban developments are built with relatively restricted soil volumes, and plants in these areas will be prone to drought stress regardless of watering practices.

Thus, there can be room for ornamental shrubs and trees in the new California, even for species that many presume to have high water requirements (roses, lilacs, ficus, and Eucalyptus to name a few), but cities will need the appropriate infrastructure to accommodate them, including adequate soil depth and irrigation practices that are optimized for deep root systems. Without these changes, the future of California’s urban tree canopy may be threatened as lawns are increasingly removed: while most people don’t specifically irrigate urban trees, California’s urban forest has long benefited from the excessive watering practices associated with lawns. Even large trees require far less water than lawns, but they still require some water in addition to local rainfall. This water will have to be provided by modest irrigation—at half the rate or less than current average outdoor water consumption—and the efficiency of the irrigation could be enhanced with low volume or drip irrigation systems.

Without proper stewardship of California’s urban ornamental gardens, the consequences for the new California will be dire. Urban trees and gardens provide a significant cooling effect, and large reductions in the extent of urban vegetation will exacerbate warming of California’s cities. What’s more, although the mechanisms are not well understood, many studies have found both physical and mental health benefits of access to urban vegetation. Finally, many people simply enjoy ornamental plants, as California’s active gardening culture shows. Ornamental gardens make cities more livable and enhance quality of life for many residents. So remove your lawn but keep your roses, and switch to infrequent, deep watering applied directly to the soil with no excess runoff. The new California will be better for it.

Diane Pataki and Stephanie Pincetl

Salt Lake City and Los Angeles

about the writer

Stephanie Pincetl

Pincetl has written extensively about land use in California, environmental justice, habitat conservation efforts, urban ecology, water and energy policy.

FULL BIO

Leave a Reply