The concept of biocultural diversity— the coming together of biological and cultural diversity—is receiving more attention recently along with an awareness that elements of cultures all around the world are deeply rooted in the nature, or biological diversity, around them, and that greater cultural diversity comes with greater biological diversity.

Cultural innovation in urban areas is often attributed mainly to the cultural diversity found in urban areas because the myriad ways that cultures and cultural elements merge, clash, interact, and rub off on each other in urban areas makes them hotbeds of innovation and creativity. Wide recognition of this fact manifests itself through the existence of programs like the UNESCO Creative Cities Network (UCCN), which includes member cities all over the world in seven categories of cultural creativity—Crafts & Folk Art; Design; Film; Gastronomy; Literature; Media Arts; and Music. UCCN recently held its 2015 Annual Meeting in Kanazawa City, Ishikawa Prefecture in Japan, a Creative City in the Crafts & Folk Art category.

From biological and cultural diversities to biocultural diversity

While cultural diversity has always gotten a lot of attention, the existence of The Nature of Cities and the lively dialogue it generates is just one example of the increasing recognition of cities as equal hotbeds for biological diversity. Parallels between urban biological and cultural diversity can perhaps be seen in the way diverse species are brought to cities—for example, as pets, ornamentals in gardens and parks, etc.—just as cultural elements from all over the world are gathered in cities to interact, interbreed, compete, survive, or perish.

This biological interaction, however, functions differently from cultural interaction in a number of ways. It can lead to problems with alien and invasive species, whereas the cultural parallel—interesting new cultural elements—is often seen as a beneficial rather than a damaging factor. Also, while some new biological variants have certainly arisen from urban biological melting pots, actual evolution of new species is subject to a much longer time scale than cultural innovation. These differences in the functioning of cultural and biological diversity in urban settings can make it harder to see what biocultural diversity means for cities.

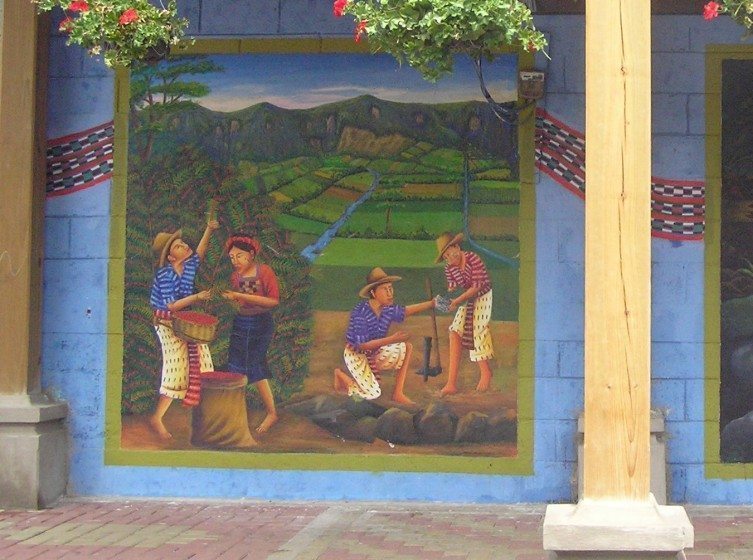

It seems intuitively true that richer biological diversity leads to richer cultural diversity if you think about the wide variety of art, rituals, traditional knowledge, etc. that are related to nature and are integral to indigenous peoples and local communities around the world. Empirically as well, greater cultural diversity has been shown (for example, in this study) to correlate with biodiversity hotspots.

From this description, it might be tempting to think that biological diversity leads to cultural diversity but not vice-versa. But in fact, the causality can work in both directions, meaning that cultural diversity can actually lead to higher biological diversity. For example, the areas surrounding Kanazawa, where the Creative Cities Network Meeting was held, are known for their satoyama landscapes and satoumi seascapes, which are places where long-term interactions between human production activities and the surrounding nature have produced a diverse mosaic of land and sea uses. This diversity of land uses comes from a wide variety of cultural practices and traditional knowledge resulting from people historically diversifying their livelihoods in order to ensure sustainable provision of ecosystem services. Diversification of livelihoods in turn results in a wider diversity of habitats within the landscape, from rice paddies to coppiced forests to maintained grasslands to sustainable fisheries and human settlements. A multi-year survey called the Japan Satoyama Satoumi Assessment found that the diverse forms of land management practiced over long periods of time in satoyama and satoumi have led to higher levels of biodiversity in these areas. Similar results have been seen (for example, here) in other human-influenced areas around the world, with higher biodiversity compared to places that have been left wild or abandoned.

A proposed model for a biocultural region

The importance of satoyama and satoumi areas for biocultural diversity around Kanazawa was on display at an event held in the city at the same time as the UCCN meeting. The event was an International Symposium titled “Introducing the Ishikawa-Kanazawa Biocultural Region: A model for linkages between biocultural diversity and cultural prosperity”, held on 28 May 2015 at Kanazawa’s 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art and organized by the United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability’s Operating Unit Ishikawa/Kanazawa (UNU-IAS OUIK). According to the event website, “UNU-IAS OUIK has been conducting research focusing on how ecosystem services are associated with interrelated cultural and biological diversity. This research looks at how the tangible and intangible aspects of culture in Kanazawa City are influenced by the ecological conditions of surrounding rural areas and vice versa.”

The event featured speakers from the Ishikawa/Kanazawa area, from around Japan, and from around the world. Among the keynote speakers were representatives from a Joint Programme between UNESCO and the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD) on “Linking Biological and Cultural Diversity”, which was established in 2010 to respond to the need to better understand the mutual links between cultural and biological diversity. Abstracts and discussion by the presenters can be found in the conference proceedings.

One of the outcomes of the International Symposium was the reading of the “Kanazawa Message 2015”, and its endorsement by the participants. The original English text of the Message is as follows:

We, the participants:

- Recognize the contribution of biological and cultural diversity to our health and wellbeing as well as to building a resilient and sustainable society.

- Support to enhance urban and rural communities towards maximizing the vitality of local power and the pleasure of ingenuity based on the use of local biocultural resources, and to create a commons and human resources for the next generation.

- Seek integral pathways to conserve, utilize and hand down local biocultural diversity and landscapes through learning each local knowledge, technologies and cultural practices.

- Promote the building a platform in which citizens, municipalities and researchers can form networks and foster exchange towards better policy development regarding biocultural diversity with urban-rural linkages.

At the international symposium, “Introducing the Ishikawa-Kanazawa Biocultural Region: A model for linkages between biological diversity and cultural prosperity” held on 28 May 2015 in Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan

The Symposium and its Message are intended to serve as an early step towards wide recognition of the Ishikawa-Kanazawa area as a model for promoting biocultural diversity, both in urban areas themselves and in terms of the ties between urban areas and surrounding rural areas. The Ishikawa-Kanazawa region’s claim to be worthy of serving as a model is due to the essential connections between the many crafts and folk arts Kanazawa City is famous for, as recognized by the UCCN, and their grounding in the nature and traditions of satoyama and satoumi areas around Ishikawa Prefecture and beyond.

The ongoing development and promotion of such a model will require a great deal of institution-building, as noted in Paragraph 4 of the Kanazawa Message above, in addition to a firm theoretical underpinning. In recognition of this, one of the keynote addresses at the Symposium was about the process leading up to the Florence Declaration on the Links between Biological and Cultural Diversity and its promulgation at the UNESCO-SCBD European Conference on Biological and Cultural Diversity in Florence, Italy, in 2014. Another example mentioned as informing the Ishikawa-Kanazawa model, this one also originating in Japan, is the Satoyama Initiative, a global-scale effort to promote the revitalization and sustainable management of so-called “socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes” in rural, peri-urban, and even urban areas around the world, including Japan’s satoyama and satoumi (for more information on the Satoyama Initiative, see the website of the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative). UNU-IAS OUIK, the organizer of the event, will be the main coordinator of institutional efforts in favor of the Ishikawa-Kanazawa model.

Finding roots of biocultural diversity

The proposal of the Ishikawa-Kanazawa region as a model for biocultural diversity brings us back to the original issue of this essay, namely: how biocultural diversity applies in cities, where biological diversity and cultural diversity apparently function quite differently. What makes the Ishikawa-Kanazawa region a suitable model to resolve this apparent conflict? The answer would seem to lie in exactly what is described in the previous section: the close ties between the urban area of Kanazawa City and the satoyama landscapes and satoumi seascapes in the surrounding Ishikawa Prefecture.

As noted earlier, it would likely take evolutionary timescales for biological processes to produce new species from urban interactions, while cultural innovations sprout quickly from urban diversity (although it would not surprise me to learn that new species have appeared recently in cities, and I encourage anyone to post examples in the comments). The biological underpinnings of cultural elements that ultimately interact in cities, however, are what make urban cultural innovations biocultural.

In the Kanazawa Message, this idea is present in its references both to “landscapes”—in the local context, meaning satoyama landscapes—and “urban-rural linkages”. Representatives from the local region at the International Symposium explicitly noted the rural origins of apparently urban cultural elements, ranging from the dyeing of silks used to make kimonos to different kinds of food culture. Food may be a particularly easy-to-understand example in that, while much of the cuisine found in the city’s restaurants represents a fusion of elements from various places coming together in the urban setting, there is no denying the ultimately rural origin of the ingredients. When seen in this light, other aspects of urban culture, art, crafts, music and others can be seen to be biocultural. Many such elements have been covered in The Nature of Cities recently. For example, regarding trees as a basis for art, where artistic techniques likely refined in urban settings are nonetheless highly reliant on nature both for content and for technology, illustrates how otherwise “urban”-seeming cultural phenomena can be described as biocultural.

The approach proposed in the Kanazawa event and ongoing work related to it is, of course, one model of urban biocultural diversity; further work will show to what extent it can be applied to different settings. In any case, it would behoove us all to keep in mind cultural aspects of biological diversity and biological aspects of cultural diversity whenever we work with the nature of cities.

William Dunbar

Tokyo

Leave a Reply