A frequent refrain in conservation is that we must prioritize. A cottage industry of conservation biologists, among whom I count myself, has risen to plan conservation and set priorities. And in nearly all of the hundreds or thousands of pages of conservation prioritizations that have already been published, nearly always the first thing let go is the nature of cities.

Transforming the human footprint means seeing people as the primary asset that we, as conservationists, can actually influence.

The argument for prioritizing conservation action goes like this: since the funding for conservation is limited, we need to make wise choices about where to invest. Good places for conservation investment are where we get the most conservation benefit for the least cost, as expressed in that most American of expressions, “the bigger bang for the buck” (which, I learned recently from Wikipedia, was coined by the U.S. military during the 1950s, for whom “bang” had a literal as well as a metaphoric meaning.)

Costs for conservation are frequently associated with human development; the more developed a landscape is, the higher the costs for conservation, a difficult but unavoidable fact of urban nature conservation. Conservation in cities is more expensive, sometimes by three or four orders of magnitude per acre, not only because the threats are more numerous and more intense, but also because of competition for land. Land for nature, or anything else, is more expensive in the city than in the countryside.

One can also argue that conservation benefits per acre, in terms of the abundance of species or the amount of intact habitat or ecosystem services, are generally higher where there is less human pressure; in other words, out of town. One might quibble that cities are often constructed in places of naturally high local biodiversity, so in the absence of development, they might actually be quite wonderful places for conservation. But the unfortunate truth is, buildings and pavement and cars usually trump natural potential and trample all but the hardiest of commensal species (e.g., pigeons, weeds, cats and dogs), unless cities are designed to do otherwise.

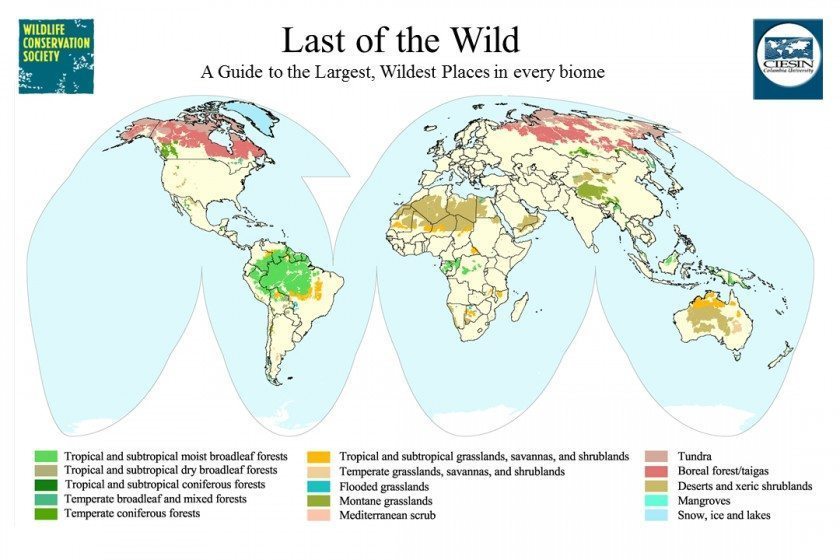

A classic conservation prioritization is the human footprint map that I helped create many years ago with some colleagues from the Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia University and at the Wildlife Conservation Society, or WCS, my home institution, which is committed to conservation of the world’s wildlife and wildest places. Through the human footprint project, we initially set out to map the Last of the Wild areas, which were defined as the places most intact in all the major biomes of the terrestrial biosphere. The trick is that intactness, as such, is difficult to identify on a global scale; what’s much easier to describe is non-intactness. In other words, to map wild places, we first mapped where people were and the ways people used the land in order to deduce, by subtraction, where people weren’t and wild places were. The Last of the Wild map that resulted found the ten largest, contiguous, wildest areas in all terrestrial biomes of the world—the places where, putatively, the bang for the buck is greatest. I’m proud to say my institution works in many of these wild places to conserve wildlife today, assembled in 15 priority regions around the world.

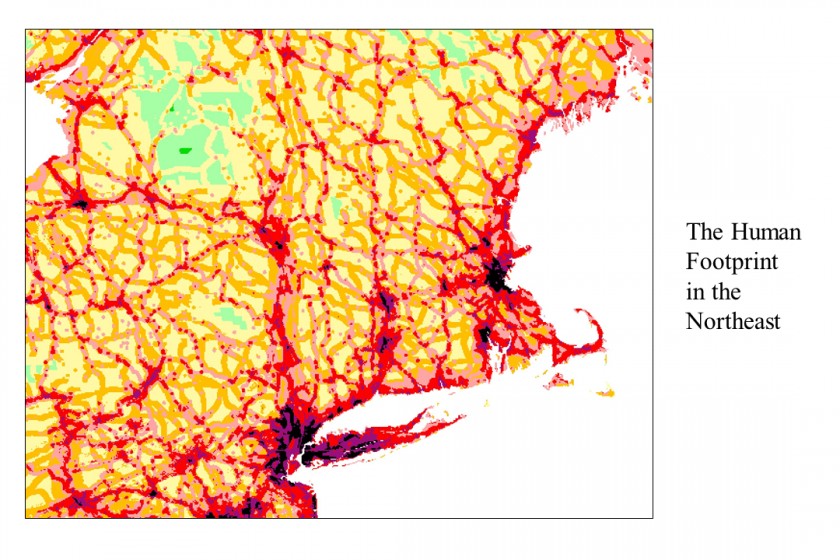

Along the way, we had once of those happy accidents of the scientific process. I remember standing in the lab watching the intermediate product—the map of non-intactness—pouring off the plotter. It was an extraordinary document, completely fascinating in its detailed depiction of towns and roads and cities and the places in-between, not just in places I knew well, but for places on the other side of the Earth. I realized that the map of non-intactness had value too. Not only did it contain the story of the wilder places of the world, but it showed them in a systematically derived index of human influence that connected wild places to cities, as they existed at the end of the twentieth century. (A new update, by Oscar Venter and colleagues, is currently under review which—the peer review gods willing!—should be out soon.) Because the map was created at such high resolution—one square kilometer pixels—one could zoom in from a global perspective to individual countries and regions and identify towns, cities, highways, even neighborhoods. The patterns made a kind of universal sense regardless of culture, education, or interest in conservation. As we colored it, one can see the wildest places in shades of green; pastures and other lightly used areas appear in light orange and yellows. One can see agriculture in its distinctive geometric shapes in tints of red and umber. The suburbs and highways pop out in scarlet and purple. And the central cities are black: cartographically, the heart of darkness.

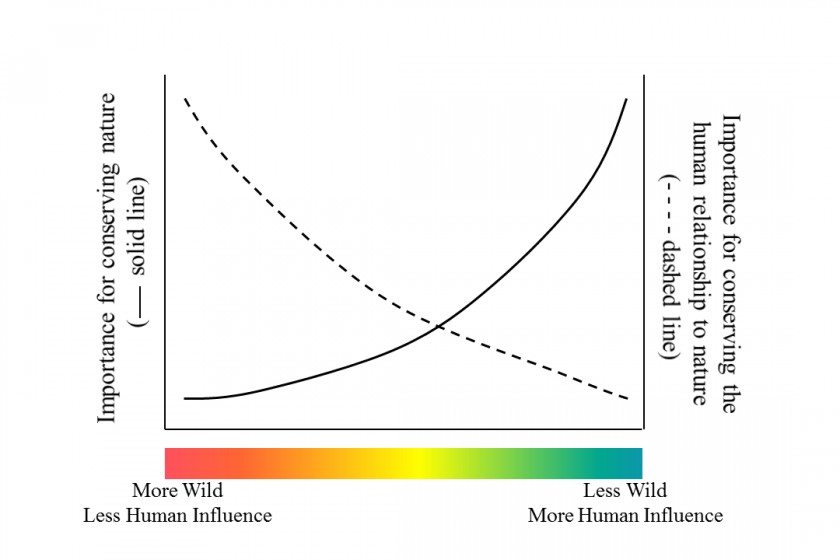

The human footprint challenged the premise for which it created. It showed a continuum, not a dichotomy. It measured relative levels of human influence, not absolutes. In fact, as I thought about it, I realized there really is no such place that is purely wild (i.e., uninfluenced); nor is there any place where nature is totally destroyed. Both of those abstractions live only in our heads. Midtown Manhattan has nature of a kind, and the biggest wilderness areas feel the troubling effects of climate change and atmospheric pollution. The entire world is caught somewhere in-between. A continuum defies binary distinctions. There are not wild places and non-wild places except as we arbitrarily draw the line; rather, there are less wild situations and more wild ones, more human-influenced localities and less human-influenced ones.

The human footprint was a turning point in my thinking, though I didn’t recognize it at the time. At first, it just meant reformulating my pitch for conservation at WCS. Conservation was about saving the Last of the Wild and Transforming the Human Footprint, one being impossible without the other. While the majority of my colleagues continued to focus on the first priority, I started to wonder about the second part. What does it mean to “transform” the human footprint?

Well, it can’t be just about the wild places and creatures, because if understanding and marveling at nature were enough, we wouldn’t have such a sprawling tangle of human influence in the first place. There must be more to it. Slowly, it occurred to me that transforming the human footprint requires understanding where the human footprint comes from. It means recognizing the reasons why the human footprint has extended so far and touched so much of the Earth, and why it is heavier in some places and lighter in others. Transforming the human footprint means seeing people not just as a threat, but as an asset—in fact, the primary asset that we, as conservationists, can actually influence. We can’t speak to tigers or rally forests or entreat the climate to sustain us. What we can do, and what conservation actually is, is about influencing people to make choices to conserve nature on behalf of us all (tigers, forests, climates, and humanity, etc., inclusive).

Seen in this way, the prioritization argument is turned on its head. If people are essential, then isn’t the biggest bang for the buck also where the people are? If one wants to conserve elephants and other wildlife, indeed we should do everything we can to save the remaining “wild” places of the world. If one also wants to conserve the human relationship to nature, cities are the highest priorities. Conveniently, the human footprint continuum is our guide either way, simply by changing the legend on the map.

Through my obsessions over the last decade and a half (The Mannahatta Project, Terra Nova, Visionmaker, Welikia, SFB4), my approach to conservation has come to focus on cities. Cities are not hearts of darkness where conservation is hard and pointless, as I once supposed; cities are shining lights that can illuminate the human relationship to nature if we help them to do so. Cities are where decisions are made and money earned and culture created. Cities are where the conservation movement arose and where it still has its strongest support, as evidenced by my own organization, founded over 120 years ago as the New York Zoological Society and still going strong with the same mission it has always had: to speak to urban people about wildlife and to save wildlife out in the world. Urban conservation gets you more minds for your buck and more hearts for your dollar.

I became an urban nature conservationist because I eventually realized that it is self-defeating for conservation to say that only nature far away and remote from view is valuable. Doing so limits our audience to the few people that live in the wildest places, who are often poor and powerless, or to the few people fortunate enough to have an experience of the extraordinary nature of the African savanna or the Patagonian coast or the Russian Far East. When we say that only wild places matter, we limit our audience to the people that already believe. Having limited our audience, we limit the resources and the support available for conservation. Having limited the resources, we then require prioritization. Prioritization of only the wild places for conservation becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy for ever-diminishing influence in the world in a time when the need for conservation, and the love conservation action expresses, is greater than ever.

For conservation to sweep society and to save the world against the enormous pressures created by the natural resource demands of more than 7 billion human beings, we have to say that nature everywhere matters and that every action in the human enterprise matters to nature. Each and every place has a role to play in the web of life, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant. If we believe that people need nature to live fully realized lives, then it is immoral to say that city people—which describes most people in a world where more than half the population is urbanized—don’t deserve nature close by. That’s why we created zoos and botanical gardens, but they are not enough on their own. We can’t say, “Nature over there is cool,” but “Nature outside your door is terrible.” Conservation must encompass nature everywhere, and that includes the nature of cities. Urban nature is our best chance to build the strongest constituency of people to care for the Earth as a whole. That woodlot in the park, that community garden up the road, that green roof on top of the building across the way, provide direct benefits to people that see them every day because they facilitate a connection to the world and build empathy for wildlife and wildness, both near and far.

I am an urban nature conservationist because I love nature everywhere and I need you to love it, too.

Eric Sanderson

New York City

Leave a Reply