This concept paper was inspired by a series of round table discussions that were hosted by the Israel Urban Forum, together with the Bezalel Academy of Urban Design in Jerusalem.

In the urban biosphere, the city is at the center and becomes an active player in the integration of ecosystems and urban communities throughout the metropolitan region.

The participants at my round table, where the topic of discussion was “The City and its Surrounding Region”, are all effectively co-authors of this piece, and their names and titles appear at the end. The resulting paper constituted one of the chapters of the report submitted to HABITAT III by the Israel Urban Forum under the general title of “Other Urbanisms”.

The question we posed was:

“Can we evolve from the traditional urban-rural divide to regional management requiring cooperation among stakeholders throughout the ‘Bioshed’?”

* * *

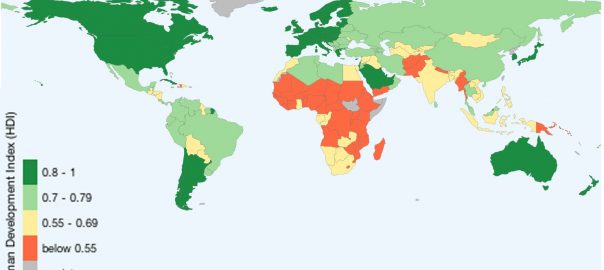

By the end of this century of cities, the global process of urbanization, which started unsustainably with the Industrial Revolution, will reach unprecedented proportions. An anticipated 90 percent of the world’s population will, by the year 2100, be living in urban settings (mega-cities, cities, or small towns). In Israel, a small country with a steep population growth curve, we have already reached that point, and one of our major challenges is to contain further urban sprawl and to discourage the establishment of new urban communities.

In our need to strengthen existing cities and to ensure that they remain compact yet sustainable, we have to face an additional dilemma: urban-rural connectivity. Within any given urban metropolitan region, there are many and diverse governing entities, none of which is answerable to the others. Some of these entities are political bodies, and include all the different ranks and levels of local authorities, whereas some are professional, dealing with the many layers of infrastructure that are needed for modern urban living. However, in spite of the inherent disconnect among all the governing entities, people living in any one part of the metropolitan region will have need of services from other parts. For purposes of employment, education, health services, recreation, business and many additional functions, people will seek solutions within the metropolitan region.

In the case of some areas of activity, there is a regional authority of some kind in place. This can usually be said of infrastructure layers such as education, health, electricity, and transportation. However, what happens to the life-giving layers of infrastructure, water sources, and natural resources? It is only in the last few decades that these latter have begun to be treated as playing a significant urban role. Even as the concept of sustainable development in general, and sustainable urban development in particular, have evolved, nature in the city has mainly consisted of what was left over after development took place, and has rarely factored into the process of city-making.

In recent years this has changed, and there is a growing understanding and appreciation of the added value of nature in cities, and of the contribution of urban nature to the well-being of city-dwellers. That said, the city-region conversation takes this thinking one step further, tackling the enormous challenge arising from the reality that natural infrastructure and its ecosystems do not line up with either municipal or even geopolitical borders. They are not sufficiently respected within the diverse units of governance, let alone recognized as a layer of infrastructure throughout the region.

Connectivity between urban and peri-urban ecosystems

“Ecosystems” are not just natural habitats secured in “protected areas” such as national parks and nature reserves, but encompass processes and any land area in which live biomass is produced by plants that use solar light, soil minerals recycled by soil micro-organisms, and soil moisture. Cities are part of the natural world. Cities therefore comprise an interactive mosaic of such areas, including parks, gardens, and natural habitats, in which buildings and other human-made infrastructures are embedded, thus making the city in its entirety an “urban ecosystem”.

Urban ecosystems generate many benefits to city residents: they regulate the urban climate and its air and oxygen concentration and quality; they reduce flood intensities and the spread of vectors of soil and airborne diseases; and they conserve soil and habitat for all biodiversity components.

These benefits, which are essential for human health and well-being, have been referred to as “ecosystem services”. However, their rates of flow may not suffice for providing all the daily needs of the city’s dwellers. Food and water are often, if not always, imported from ecosystems outside the city. Thus, just as the built-up entities of the urban ecosystem are embedded in the city’s biodiversity habitats, the urban ecosystem itself is embedded in an often expansive mosaic of natural, planted, and agricultural ecosystems, not to mention smaller urban ecosystems within the region.

The cultural services provided by the intra- and inter-city, or by the city and the peripheral natural ecosystems and their biodiversity, include the options of healthy leisure, recreation, and inspiration available to the city dwellers and their communities. However, it is important to highlight the interaction between the city and the off-city ecosystems and their biodiversity, in a synergistic provision of ecosystem services for residents of the city and the urban periphery.

It is only in the last few decades that the urban role of natural systems has been addressed. The effective management of these systems is rendered harder simply because they don’t align with any existing boundaries, and are barely taken into account within each unit of governance in the region. A joint and interactive planning and management of the urban and regional ecosystems is therefore mandatory, since they are interdependent, and the protection of ecosystems at all scales is necessary for sustainable urban development.

Planning across scales must also extend to the larger national scale. Only in recent years has the need to integrate ecological corridors into the national planning grid been understood. What is quite new and in need of wider and deeper understanding is the potential role of cities and the metropolitan areas around them in supporting the continuity of these essential corridors. Even a small-scale neighborhood plan could wreak havoc with a national-scale ecological corridor. However, if understood and implemented properly, that same small-scale neighborhood plan could not only support the connectivity of the national ecological grid, but could also bring great benefit to the local residents, giving them a valuable cultural and recreational asset.

The urban biosphere

The urban biosphere provides a framework through which the vision presented above could be achieved. Its goal is the sustainable development of the large city at the heart of the metropolitan region, in collaboration and cooperation with the other smaller urban communities around it. This is not a structure of hierarchy, but of consensus and dialogue.

Formally, a biosphere of any kind has to earn its definition as such through a process under the supervision of UNESCO’s Man and Biosphere program. However, the actual process of designation is perhaps less important than the concept itself, especially in the case of the urban biosphere, as developed jointly by ICLEI, the sustainable cities’ network, and academic partners, including the IUCN. A Jerusalem team, together with the Jerusalem Municipality, took part in the initial development of this program between 2010–2013. This led to the establishment of the Jerusalem Bioregion Center for Ecosystem Management in 2014.

Although regional, cross-boundary management of natural resources is essential, none of the local authorities in the region have the statutory capacity to do so. This is the point at which civil society initiatives, such as the Jerusalem Bioregion Center, can potentially play a significant role by developing a non-hierarchical framework for cooperation among the many and diverse authorities and organizations in the region. Local government and academia are also essential partners.

In the urban biosphere, as opposed to the traditional biosphere reserve, the city is at the center, and becomes an active player both in the integration of ecosystems in urban development, and in encouraging the other urban communities in the metropolitan region to work together.

In the framework of the urban biosphere, not only are regional natural systems recognized as infrastructure in their own right, but they are understood as the natural resources that give us life. This understanding will influence planning, education, culture, recreation, and all of the other urban frameworks, not in a way that impedes development, but in a manner that strikes a balance between the needs of urban communities and the requirements of natural systems. This framework underscores the City’s obligation to deal with the quantities of garbage and waste that it traditionally dumped in sensitive areas beyond its boundaries. It would protect natural infrastructure during the development of transport and energy systems. Containing the city and keeping it compact remains a major goal, but no less important is the need for connectivity between urban and peri-urban nature. This transformation in perception of the urban context cannot be brought about by a “decision-making” process alone, but the greater part of the effort would be in educating hearts and minds among all the communities in the region.

Four “biosheds” or biomes

In Israel, dynamic urban challenges necessitate a new approach, especially in the current geo-political situation. The urbanization of the four metropolitan areas requires conceptual consolidation within the context of the country and region. This means that in tandem with this expansion of urbanization, the open spaces in all their manifestations need to be reviewed and considered in two distinct contexts. First, there is a need to identify open protected areas, and to ensure that stringent guidelines are in place for their protection. Second, it is important to emphasize four regional biomes and their ecological corridors, including the peri-urban areas. The linkage of the intensive urban areas with open protected forests and reserves, through recognized and protected ecological corridors, can generate the synoecism we need in order to preserve and benefit from the many cross-boundary ecosystems.

At the global level, this relates to the IUCN urban protected areas, the UNESCO urban biospheres, the 2011 Recommendation for Historic Urban Landscapes, and the World Heritage cultural landscapes. At the local level, a range of legal devices exist, but have yet to address, these issues in a comprehensive way. It should be noted that the Israeli Planning and Building Law specifically indicates objectives regarding the control of development and provisions for conservation and environmental conditions, while the Israel Lands Authority Law opens with the need to provide a balance between development and conservation on the one hand, and reserves for future generations on the other.

There are at least four potential biomes or “biosheds” (an organizing concept coined by Jennifer Rae Pierce of Central European University, 2014) in Israel, but to date Jerusalem is the only one where this process of ensuring connectivity has been attempted. It is the most complex bioshed of the four, and it is not surprising that the current initiatives of cross-boundary ecosystem management are products of the bottom-up, multi-stakeholder process led by the Bioregion Center, rather than mandatory processes dictated by the different levels of government.

One important way to counter unsustainable development pressures is to foster the inherent but often forgotten linkage between culture and nature, by adopting a policy for culture as an enabler of sustainable development. This should marginalize speculative development and short-sighted planning decisions, which will exchange the urban problems of today with new and more complex urban and national problems of tomorrow. Making our cities safe, inclusive, sustainable, resilient, and green requires an integrative approach in which global and local mechanisms are better connected through the application of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals in general, with special emphasis on Goal 11.

Resources must be provided for local governments through regional initiatives, together with education and awareness programs, that can better address the relationships between human and natural habitats. The role of academia in highlighting the research in these fields, alongside that of civil society in raising the consciousness of its importance to the well-being of society, will be critical in generating new approaches. “A successful sustainable development agenda requires inclusive partnerships … built upon principles and values, a shared vision, and shared goals that place people and the planet at the center.”

Urban agriculture and the local food cycle

The ecosystems layer of infrastructure throughout the city and its surrounding region connects with another very important infrastructure layer: the food grown, marketed, and consumed in and around the city. Significant bottom-up entrepreneurship has been impacting national policy throughout Israel, and it is a trend that should be encouraged. People grow food locally for many different reasons; in some cases, the focus is educational, whereas in others, it is a community initiative. There is an increasing number of commercial initiatives, whether on roofs or on the ground, inside the city or in peri-urban areas. In parts of Israel, notably in the Jerusalem region, part of the tourist’s cultural experience can be to participate in farming on ancient agricultural terraces that have been used since Biblical times.

The urban agriculture movement is playing an integral role in the growing Israeli urban movement. It brings together environmentalists, whose concern is to cut down the heavy ecological footprint of importing fresh food. It attracts health and nutrition experts, who realize the value of food growing as a personal experience that brings children and adults pride of ownership of the food they grow and encourages healthy eating. Resilience experts appreciate that a city with its own food production capacity is potentially more food secure in any kind of emergency. In economic terms, a local food system can provide livelihoods for an entire chain of food-growers, markets, and eateries, to mention only a few. Last but not least, biodiversity experts see urban agriculture as an opportunity to wean some of our food production away from the vast extra-urban areas of monocultural food growing, which many think constitute a greater threat to nature than our cities. In addition, when roofs and neglected open spaces in cities are used to grow food, there are many additional benefits. Food-bearing trees provide shade, and well-tended herb and vegetable plots provide new urban opportunities for butterflies, bees, and frogs, not to mention the half a billion birds migrating bi-annually over Israel, for whom a local community garden could make all the difference, offering valuable rest and sources of nutrition on their long north-south journey.

In conclusion, I wish I could give an unequivocally positive answer to the question we posed in our round table discussion. Jerusalem has established what I believe is an excellent framework, in the Bioregion Center for Ecosystem Management. However, in our special bioregion, which encompasses a wide spectrum of cultural and geopolitical human diversity, as well as its rich biodiversity, while many more stakeholders are at the table than we had at the beginning, and a lot of hands-on projects are happening, the way ahead is fraught with many challenges, not least the charge which is frequently leveled at us, that we are simply naïve and unrealistic as to the true problems of our region. As the Israel Urban Forum develops, we will try to have this model adopted in the other three potential bioregions, in the hope that our bottom-up approach will ultimately impact official national urban policy.

* * *

I hope the ideas presented here will lead us into a continuing discussion of the special relationship between big cities and their metropolitan regions, and I would like to thank the people (listed below) who contributed their ideas to this concept paper. The round table team gave me permission to use their comments and I have incorporated much of what was said, and later summarized, into this section of the report.

Naomi Tsur

Jerusalem

Prof. Mike Turner, UNESCO Chair in Urban Design and Conservation Studies, Bezalel Academy

Prof. Uriel Saffriel, Chair of the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Committee, Israel

Dr. Nati Marom, Chair of Sustainable Development, Interdisciplinary School, Herzliya

Anat Gold, Director of Strategic Planning, Jewish National Fund

Hadas Bashan, Biosphere development, Jewish National Fund

Arch. Yael Hammerman Solar, Director of the Gazelle Valley Park, Jerusalem

Pazit Schweid, Director of Urban Communities, The Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel

Galia Zuckerman , lecturer and entrepreneur on urban agriculture

Yael Bruchin, Environmental Education Consultant

Helene Roumani, Director of the Jerusalem Bioregion Center

Leave a Reply