about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

“Biophilia” as an idea describes how people have innate love for, attachment to, and even need for nature. It also expresses the notion that, as a design imperative, cities are more livable when they have more nature, and that people are happier and healthier when they have more contact with nature, from wild parks away from buzzing traffic all the way to street trees and flowers in tree pits.

It sounds nice.

So, how can a city transcend the metaphoric qualities of “biophilia”—nature is good, who would argue with that?—and define something actionable? For example, how much nature is “enough” nature in a city? Or, how much biophilic experience is enough? What does “enough” mean? Does walking past 50 street trees equal, in terms of a biophilic dose, a hour in a park? Do workplaces designed with biophilia in mind compensate for less nature outside. The research questions are rich and extensive, and their potential connection to design is important.

Stated in these ways, the questions of biophilia become about goal setting and targets. This is the focus of this roundtable. Is biophilia an actionable driver of design in cities? If so, what should cities have as targets or goals for biophilia? If the aim is to create a “biophilic city”, how would you know when it was achieved? Perhaps the measures won’t be found in metrics of nature, but in metrics about people and their perceptions of and feelings for nature.

Several contributors wonder, however, whether talk of metrics somehow misses the point of biophilia. It leaves us with the key prompt: Specifically, what are we trying to accomplish with biophilic cities?

about the writer

Lena Chan

Lena Chan is the Director of the National Biodiversity Centre (NBC), National Parks Board of Singapore.

Lena Chan

What are the components of a city? They are commonly assumed to be the buildings, infrastructure, and open spaces. But it is the interaction between the living organisms, including people, plants, animals, microorganisms, etc. and the physical man-made features that make a city a dynamic entity!

A biophilic city should encompass all aspects of a city, both the software and the hardware.

Can a truly biophilic city exist, or is it just a utopian dream?

The challenge is that the goals of a biophilic city should encompass all aspects of a city, both the software and the hardware. Biodiversity considerations should be taken into account in the development processes of a city. The city will not be able to do this unless it knows what biodiversity thrives in it. Everyone must play a part to actualise the goals.

I would like to relate a case study of a city that embodied biophilia. A man had a vision and he planted a tree on 16 June 1963 which grew into the Garden City programme. This programme became the mission of a city-state which evolved into a City in A Garden (see also Tim Beatley’s contribution to this roundtable). That man with foresight was the late Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, and the city is Singapore.

In 2015, the National Parks Board (or NParks) of Singapore decided that it was time to systematically consolidate, strengthen, and intensify its biodiversity conservation efforts. This formalization process is manifest in NParks’ Nature Conservation Masterplan (or NCMP).

The NCMP comprises four focuses: 1) Conservation of Key Habitats, 2) Habitat Enhancement, Restoration and Species Recovery, 3) Applied Research in Conservation Biology and Planning, and 4) Community Stewardship and Outreach in Nature. The goals and targets of a biophilic city would be to ensure that all four of these aims are synergised and implemented successfully.

Some of the actions that can be taken to ensure the successful implementation of the first aim are the identification, safeguarding, and strengthening of the most important biodiversity areas that harbour the bulk of the native gene pool; the enrichment of buffer areas and ensuring that land use is compatible with that of the important biodiversity areas; the enhancement and management of additional nodes of greenery throughout the city, such as parks, roadsides, roof-tops, vertical and sky rise greenery, etc.; and the development of ecological corridors so that the effective area that can be used by wildlife is enlarged.

Most urban areas are degraded; hence, habitats for wildlife should be enhanced, restored, or created as targeted by the second of NParks’ aims. Rare species can only be sustainably conserved if the condition of the ecosystems that they thrive in is good.

Applying state-of-the-art technology would greatly assist in the achievement of the third aim. Indeed, the application of modern technology to biodiversity conservation work, including the use of geographical information systems, drones, 3D modelling, agent-based modelling, genomics, etc., has made possible much data collection and analyses that eluded us in the past.

Without community stewardship and public outreach, the efforts towards a biophilic city would be meaningless and would not be sustainable on a long-term basis. Biodiversity should be incorporated into the curricula of all levels of the education system. To build more ground support, we must also encourage citizen science.

There are many cities around the world that are biophilic in their own special way, including, Curitiba (Brazil), Edmonton (Canada), Montreal (Canada), Bonn (Germany), Nagoya (Japan), Wellington (New Zealand), and more.

Right metrics for measuring progress toward these goals

How can the success of achieving the goals of a biophilic city be measured?

In May 2008, the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, alongside the Global Partnership on Local and Subnational Action for Biodiversity (or GPLSAB) designed a self-assessment tool for cities to benchmark and monitor the progress of their biodiversity conservation efforts against their own individual baselines. This index is now referred to as the Singapore Index on Cities’ Biodiversity because of the pivotal role Singapore played in its creation and spread.

Determining an optimal number of indicators is not easy: if there are more than 30 indicators, it would be too onerous to assess, whereas fewer than ten indicators would compromise the robustness of the assessment. The GPLSAB tried to strike a balance with 23 indicators that first measure native biodiversity in the city; then measure ecosystem services provided by biodiversity; and, finally, assess governance and management of biodiversity. To be scientifically credible, the indicators we use must be quantifiable so that they can be verified by independent evaluators. Hence, each indicator is assigned a scoring range between zero and four points.

To date, 25 city governments have applied the Singapore Index (or SI). Academics have applied the SI to an additional 14 cities, and 11 more city governments are currently in the process of applying the SI. Academics who research biodiversity indices for cities have found that the SI is the only index currently in use for measuring biophilia—Timothy Beatley collated a list of indicators of a biophilic city in his book, “Biophilic Cities: Integrating Nature Into Urban Design and Planning”, but did not cite how these indicators were applied.

Any city can be a biophilic city—but becoming biophilic is made that much easier if all its citizens embrace biophilia into their ethos.

A city becomes biophilic when each year:

1) The area of green cover and tree canopy increases

2) More natural and human-created habitats are enhanced and restored with native species

3) The number of native species escalates due to discovery of new species, re-discoveries of species thought to be extinct, and new records

4) The participation rate of citizen scientists expands, and

5) Over 50 percent of the residents can name and recognize at least ten native plants, birds, and butterflies.

Cities, join in this challenge, and enjoy your journey to becoming truly biophilic!

about the writer

Ian Douglas

Ian is Emeritus Professor at the University of Manchester. His works take an integrated of urban ecology and environment. He is lead editor of the “Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology” and has produced a textbook, “Urban Ecology: an Introduction”, with Philip James.

Ian Douglas

My first memories of urban nature are how my father grew vegetables in our London suburban garden. He had dug up part of the lawn to increase the area used for growing vegetables. The other part of the lawn still had flowerbeds at the side, but there were also blackberries, and, farther down, the garden fruit trees and a larger area of vegetables. A few hundred metres from the house, the local golf course had been ploughed up to grow wheat. My childhood escape to wilderness was to find a path through the wheat to an overgrown bunker, which still had trees, and to me was an island in a sea (of wheat).

Forms of urban biophilia that emerge from wars and strife provide lessons in making biophilia work.

The park opposite my primary school had been almost totally dug up for vegetable allotments, as had most of the sports ground belonging to the company for which my father worked. My aunt kept chickens in her garden and we placed food scraps in the trash bin in the street, which I knew as the pig-swill bin. The food waste was collected and taken to pig-farms that had been established in the local area to enhance the meagre wartime meat rations. Looking back at this time, I now interpret this as a biophilia of necessity, a forced biophilia far beyond the control of any family or local community. The London suburbs at this time were part of a special kind of biophilic city.

A different awareness of urban nature came ten years later, when our sixth-form history teacher took us to the City of London to look at the remnants of its past that had survived wartime bombing. I was amazed by the way plants had colonised the bomb sites, with a great diversity of flowers and foliage, containing many species that I had not seen before. This spontaneous urban vegetation had caught the attention of many naturalists and ecologists, including E.J. Salisbury and R.S.R. Fitter, whose writings eventually led to the creation of urban ecology parks on pieces of neglected, derelict land (a story told brilliantly by David Goode in his “Nature in Towns and Cities”).

A different perspective on urban biophilia arose 12 years later, with my first experience of a tropical city which then had considerable poverty. In Kuala Lumpur, on the banks of the Sungai Gombak, people were cultivating vegetables; patches of land between buildings were used as temporary, precarious gardens, even within a metre or two of heavy traffic. Here was an urban agriculture of necessity: a subsistence biophilia that risked flood damage, pollution and contamination to increase families’ food security.

By 1999, 800 million people worldwide were engaged in crop, livestock, fisheries, and forestry production within and surrounding urban boundaries. In many low latitude countries, over 30 percent of households are engaged in urban food production, with over half the poorest 20 percent of households relying on growing their own food. This represents another form of biophilia arising out of need. However, other biota, especially insect pests and disease vectors, pose major problems for these communities. If adequate water, sanitation, and drainage could be provided to the informal settlements in which most urban farmers live, the problem biota could be greatly reduced and the benefits of urban greenery could be enjoyed by more people for longer.

Following the 2001 economic crisis in Argentina, 60 percent of the inhabitants of the city of Rosario had incomes below the poverty line and 30 percent were living in extreme poverty. Urban food production using vacant land was encouraged and incorporated into municipal policies. A biophilic city developed, with specific provisions for the agricultural use of public land and a municipal “green circuit” consisting of family and community gardens, commercial vegetable gardens and orchards, multifunctional garden parks, and “productive barrios”, where agriculture is now integrated into programmes for the construction of public housing and the upgrading of slums.

Rosario, and my other examples of forms of urban biophilia that emerge from wars and strife, show that, when there is political will and a clear policy of social inclusion, it is possible to incorporate urban agriculture into a wider urban green infrastructure and create a biophilic city that is socially inclusive and provides equitable access to ecosystem services.

For further information on Rosario go to: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i3696e.pdf.

about the writer

Chantal van Ham

Chantal van Ham is a senior expert on biodiversity and nature-based solutions and provides advice on the development of nature positive strategies, investment and partnerships for action to make nature part of corporate and public decision making processes. She enjoys communicating the value of nature in her professional and personal life, and is inspired by cooperation with people from different professional and cultural backgrounds, which she considers an excellent starting point for sustainable change.

Chantal van Ham

A growing body of evidence suggests that early childhood experiences with nature provide physical and mental health benefits, stimulate child development, and can help to generate a lifelong sense of connectivity and stewardship towards the environment—yet urbanization poses a growing challenge to these types of experiences (Revolve Magazine Spring issue 2017). We are part of nature, but in a rapidly urbanizing, noisy world, filled with entertainment and technological innovation, it is easy to forget that the state of the planet reflects the well-being of its inhabitants. Restoring the connection between people and nature is the foundation for improved quality of life.

Cities that prioritise green space development and budgetary input from citizens show how biophilia can be achieved in urban spaces.

I believe there cannot be enough nature in cities, particularly if we think of the diversity of benefits it can provide to urban citizens, from reduced risk of stroke, cardiovascular disease, and obesity to lessened symptoms of anxiety and depression. I grew up in a small village in the countryside in the South of the Netherlands, and nature captured my heart from a very young age. I can only imagine how different it must be to connect with nature when growing up in a city.

I believe that stewardship for nature comes only from the heart, from within, wherever we live. Experiencing nature—especially in early childhood—counts, and therefore it is important that people who live in cities can connect with nature close to their homes. If we want to restore this connection, it is also essential to educate people all around the world as to why nature is special; there are many ways of doing this.

Cities that prioritise green space development share core attributes: they protect, value, and celebrate their natural assets through education, community engagement, and monitoring and sharing successes. The inaugural issue of the Biophilic Cities Journal, launched in February 2017, is filled with inspiring examples, such as Vancouver’s Biodiversity Strategy; Pittsburgh’s riverfront trails and parks; the Butterfly Highway in Charlotte, NC; and the Oak Bottom wildlife refuge in Portland. These show how achieving biophilia in cities can be done.

In Europe, cities in different countries, such as Poland and Belgium, give citizens the opportunity to participate in decisions on how the city budget is spent. This offers a good starting point for dialogue, ownership, joint responsibility, and stewardship for the results of these decisions. Antwerp, for example, works with a citizen budget in several city districts, which gives citizens the chance to decide about the thematic priorities in which the city will invest. This means that they will become partners in policymaking, and city planners get better insight in their expectations, dreams, local sensitivities, and interests. This video shows some of the projects that have been realized in Antwerp in 2016 thanks to citizens’ involvement in the budget decisions. Over the last four years, Wroclaw, Poland—Cultural Capital of Europe in 2016—has opened 30-40 percent of its budget for citizen decision-making. It is perhaps too early to assess the results and compare the impact on nature as a result of citizen involvement in comparison to traditional decision-making, but it seems to be a positive way for co-creating public spaces and stimulating creative ideas and social cohesion across the city.

Setting goals and targets and developing metrics for measuring improvements for a biophilic city must start with awareness, ideas, and actions that are in harmony with nature—and by engaging all who make part of the city in developing its future.

about the writer

Mike Wells

Dr Mike Wells FCIEEM is a published ecological consultant ecologist, ecourbanist and green infrastructure specialist with a global outlook and portfolio of projects.

Mike Wells

Biophilia is about humans’ love of and response to nature, and many will naturally consider that designing to nurture this “weak innate tendency” is pretty much solely about humankind; that is to say, it’s about how we can create better, healthier, more productive lives for Homo sapiens—the “clever”, and now predominantly urban, species.

Perhaps the greatest risk inherent in the concept of biophilia is its very anthropocentricity.

It has been argued elsewhere that a key value of emphasizing biophilia is in getting us not only to cope with, but to prefer, high density urbanism, which will in turn help us to avoid urban sprawl with all its damaging resource use inefficiencies. This is a key theme that my colleagues and I have developed over many years, and which I believe to be more important now than ever.

Biophilic cities, however, must be about more than that. Perhaps, ironically, the greatest risk inherent in the concept of biophilia (as with sustainability) is its very anthropocentricity—its focus on urban humans and their well-being and comfort. I would like to explore this paradox a little in this short contribution.

I began my career not in cities, but in remote parts of the globe studying flora and fauna in wild (or semi-wild) places. Wherever in the world I have worked or visited, the pressures of anthropogenic habitat loss, extinction of species, and general degradation of the biosphere have been patent and distressing. We have little time to save a world worth living in and passing on to our progeny. We have used multiple methods for addressing this crisis of global biodiversity loss, all of which are part of the solution. Most governmental and scientific approaches these days focus on serious and pressing issues of economics and livelihoods of those in poverty and on fighting ecosystem imbalance that lead to disease. Nevertheless, the threats from development; population increase; resource demand and depletion; pollution; and warfare become ever more acute. We are reduced to drastic decisions over where to spend limited conservation resources or how to extract DNA from vanishing species in the hope that some future generation may be able to reconstitute what has been lost. We are locked in endless struggles to fight off particular threats, such as intense poaching, to feed cultural urban markets for ineffective cures. We are not winning overall—instead, we are driving the mass species extinction of the Anthropocene.

That is why I personally switched my attention from working in the wilds to focussing on design of the urban realm at a midpoint in my career; and to the pressing concern of how to change human attitudes and behaviours, altering the hearts and minds of urban citizens and consumers, towards a fuller understanding and love of nature. I was not then versed in the statistics of global urbanisation. But now I know that in about 30 years hence, 70 percent of us will probably live in cities. Any rural poor that remain in the countryside will be vying with the urbanites for scarce resources. Something, somehow, has to be done to reset our balance with nature, or we face a world reflecting some of the starkest views of science fiction, perhaps with nature reduced to simulators and our living space to “caves of steel” enclosures.

To me, biophilia is the latest useful conceptual mechanism in the armoury we have to save the overall biosphere in a condition worthy of the name. Most of us appear to be aware deep down in our psyches that we need nature. The power of the biophilic response, as opposed to the value of other urban ecosystem services, is that it relates to primal emotions that are considered innate. It is also one that auto-reinforces; when the weak tendency from childhood that has atrophied in adulthood is rekindled, it can grow. And the importance of this is that we have now reached a point where logical, numbers-based arguments, though having an important role to play in saving and promote nature, are not going to be sufficient to save nature from anthropogenic decimation.

We need to appeal to our deepest positive emotions and instincts. Biophilic theory—and, now, the theory of biophilic design—have raised the potential to tap into these emotions and instincts to a new level of professional focus and, thus, action.

Recent publications on “biophilic cities” have described in some depth the struggle there has been to define what such a city looks like. Many of the images that we love and use when talking of biophilic cities, from Gardens by the Bay Singapore, to Bosco Verticale in Milan, to the Acros Centre in Fukuoka, strongly tap into the health and well-being responses in people that so many new research initiatives are quantifying and documenting.

But the creation of a love of, and respect for, wider nature, including those parts of it that we might not even know about, or ever directly encounter, is, to my thinking, every bit as important as focussing on our own urban well-being. Generating this emotion follows the degree to which biophilic city programmes can be shown to change how much urban humans starts to care for “that which is other” and should be a primary metric of their success. We need to look hard for shifts in cultural attitudes and voting opinions from dominion over and use of nature, to ones of precautionary restoration, stewardship, inquisitiveness, and wonder. The metrics could be varied, but would probably be based on social, political, and psychometric surveys of citizens.

The types of measures implemented to achieve this goal may differ from those that comprise the most frequent components of the biophilic design canon at present. What those measures need to be could be the subject of a future contribution to TNOC. What is certain is that they need to work very strongly to awaken human awareness of, and care for, global biodiversity, and not just those parts of it with which we share our cities.

A final thought

There is even a risk that, by focussing on the urban ecosystem services that nature provides to us to make our lives better and more comfortable in the cities where we now spend most of our time, we could actually be distracted from thinking about the wider plight of nature. We may be lulled into feeling that all is well with the world in our nice, verdant urban realm.

Perhaps we also need, at times, to be made to feel uncomfortable, sad, compassionate—even desperate—about the plight of the wider natural world.

This is a very fine balance to strike.

Several times in my life I have had the pleasure of speaking with David Attenborough and, on the last occasion, I asked him why he does not directly present more hard hitting messages about humans’ harmful stewardship of the natural environment more often. He told me that he saw his main skill and main role to be inspiring people about the wonders of nature, and that from that love, perhaps sustainable stewardship would emerge. As an experienced broadcaster, he was all too aware of the risk of overloading viewers with depressing news to the point that they will “turn off”.

So, we need to employ all of our skill to create both nature-inspired wonder and knowledge-informed concern and action for nature in equal measure, in the effective “biophilic city”.

about the writer

Jana Söderlund

Dr. Jana Söderlund has spent her career being active as a sustainability consultant, environmental educator, tutor, lecturer, and presenter.

Jana Soderlund

My vision of a biophilic city is one in which city planning and design facilitate a seamless integration of the natural and built environment. A city where nature is given equal status to roads and buildings, or even takes precedence. City dwellers are healthy and happy, commuting through innovative electric vehicles, or simply just walking and enjoying the beauty of the city. Dedicated green corridors connect the city to its bioregion and provide safe pathways for local fauna. Biodiversity is flourishing. The urban heat island is a memory.

By looking at how smaller biophilic visions have been achieved, we can transition sterile, mechanistic, post-modern cities towards connectedness between nature and humans.

If we could start building a city from scratch, this vision is possible. The technology and the economics are there to support it. But the reality is that many cities are a long way from this biophilic ideal and the question is: How can we transition sterile, mechanistic, post-modern cities towards achieving a biophilic city of connectedness between nature and humans?

By looking at how smaller biophilic visions have been successfully achieved globally, we obtained an understanding of the metrics needed to move cities towards biophilic nirvana. This required an investigative, immersive journey to explore the origins of biophilic design and to meet with forerunners in the field as a way to gain an understanding of what motivated them to create a social movement of change in the way we design our built environment. The journey also explored examples of biophilic initiatives and how these had coalesced from the early conceptual ideas.

The first and most obvious commonality between these early initiators was a connection to nature, an understanding and intuitive knowing that the inclusion of biophilia in our cities is the way forward. Conferences were held which united these interested players and frequently resulted in the emergence of a local champion. Local champions are important to nurture, as it is often solely their passion, their vision, and their motivation that drives a movement forward. These leaders all appeared to have an undiminishing sense of wonderment about nature and the most frequently expressed word to describe their feelings in nature was peace, followed by wonder. The concept of biophilic design, when researchers or practitioners discussed or presented it at lectures, often attracted comments that this is common sense and why do we need research about what is intuitively obvious? For most, these beginning internal motivators coalesced into drivers of external action, which then advanced the social movement.

This is a social movement which needs to include nearly every profession and area of knowledge. Collaboration and integration of silos of knowledge, and the arenas of government, community, and industry, are essential in the delivery of biophilic outcomes. It is through this collaboration that the multiple benefits of biophilic design become more apparent.

The social and environmental benefits unite to create the economic benefits, thus presenting the necessary business case. The barriers need to be identified for each design approach and profession involved. By doing this, and through creating partnerships across the silos, there is greater potential for case studies and demonstrations to be implemented.

As people innately respond to the biophilic aspect of the demonstrations, a ripple effect of implementation is created. This brings further opportunities for the multiple benefits to become apparent, and for people to enjoy the aesthetics and benefits of increased livability and well-being for urbanites.

As implementation, also driven by the recognition that biophilic design features can address local urban crises, expands, there is increasing opportunity for integration into the professions through education and practice. Government strategic policy and delivery structures are needed for industry and business. Where community has come together and initiated biophilic principles, government needs to ensure that policy does not block these actions but enables and supports local champions in combination with professions and research.

With progression in biophilic design initiatives and greater implementation, the opportunity for innovation and research increases conjunctly. The complexity of components and influences on biophilic design and planning outcomes necessitates the need to consider potential innovation and change in any one part with an adaptive system that responds to change. Active reflection is vital to keep moving forward, with the sharing of knowledge and ideas through online media, articles, and research to continue the inspiration.

about the writer

Tim Beatley

Tim Beatley is the Teresa Heinz Professor of Sustainable Communities, in the Department of Urban and Environmental Planning, at the University of Virginia, where he has taught for the last twenty-five years. He is the author or co-author of more than fifteen books, including Green Urbanism, Native to Nowhere, Ethical Land Use, and his most recent book, Biophilic Cities.

Tim Beatley

About three years ago, we launched the global Biophilic Cities Network, and it has been getting a lot of attention and gaining traction in recent months (see www.BiophilicCities.org). To join the Network requires the adoption of an official resolution or statement of intent to become a biophilic city, among other requirements. Recent additions to the Network include Washington, DC; Edmonton, Canada; and Pittsburgh, PA. These are cities on the edge of what we describe as a global movement.

Biophilic cities are nature-immersive, shared spaces of wonder and coexistence. They want nature everywhere, at multiple scales—from rooftop or room, to region or bioregion.

The BIophilic Cities movement represents an important shift in our vision of cities. There is no question we still need to design and plan cities that are sustainable and resilient, but increasingly we realize that they must also be joyful, restorative, wondrous places: places that allow for human flourishing. Genuine and full human flourishing requires, I believe, contact with nature—not just on the occasional vacation, but nature that is all around us (ideally all the time), in the urban neighborhoods and communities where we live and work. Biophilic cities put nature at the center, and that urban nature can and should take many forms—biodiversity and remnant and restored ecosystems, but also new, more human-designed forms, including living walls, rooftops, and nature included in the vertical spaces of tall buildings, among others. Abundant nature and nature-experiences are central. Biophilic cities seek to maximize the moments of awe and connection, whether it is the sight of a Humpback Whale in the Hudson River or an encounter with a line of pavement ants. We sometimes speak of a need for a “whole-of-region” approach or goal (we want nature everywhere, at multiple scales—from rooftop or room, to region or bioregion—ideally integrated, and in all the space between). And our notion of biophilic cities is also “whole-of-life”—it must provide rich, abundant opportunities to experience nature from early childhood through to our senior years.

We must push our vision even further and many of our Network Cities are increasingly aspiring to a model of natureful cities that is profoundly more immersive: the idea that we don’t just want to visit nature in cities, we don’t just have trees and parks. Rather, these places aspire to a vision of cities where the city IS the park, IS the forest, IS the garden. Singapore’s official change in its motto from garden city to “a city in a garden,” is one important example (and involved much planning work to bring about: see our film about Singapore, a biophilic city).

Biophilic cities are defined by more than just the presence or absence or biodiversity or nature, but also by the extent to which residents in these places are engaged in enjoying, participating in, and caring about this nature. We aspire to cities where citizens spend much more of their time outside, are able to recognize common species of flora and fauna and fungi, where over the course of a day, there are many moments for personal or collective awe. We want cities where there is a culture of curiosity about nature, and a culture of caring about, and caring for, the local nature. Biophilic cities understand urban environments as spaces shared with many other forms of life, and recognize an ethical duty to work towards co-existence.

Two cities that have recently joined the Network exemplify this spirit of caring and co-existence. Austin, Texas, now famously celebrates the arrival each spring of the 1.5 million Mexican Free-Tailed bats that take up residence under the Congress Avenue bridge. Thanks to heroes such as Merlin Tuttle, founder of Bat Conservation International, Austin residents shifted remarkably in their view of the bats, from biophobia to biophilia. In Tuttle’s recent book, The Secret LIfe of Bats, he describes Austin as “A City that Loves Bats.” Several years ago, we filmed a segment about the bats for a documentary film called The Nature of Cities (You can watch the segment here). It was wonderful to see firsthand the palpable excitement and fascination and anticipation of (especially) the kids waiting to see the emerging columns of bats that evening.

The City of St. Louis is our most recent member of the Network (officially entering the Network in March 2017!). Here, fervor surrounds butterflies in much the same way as it now surrounds bats in Austin. Through the leadership of Mayor Francis Slay, and Sustainability Director Catherine Werner, the city has taken many steps to educate about and promote habitat creation for Monarch Butterflies. They set a high goal of planting 250 butterfly gardens through an initiative called Milkweeds for Monarchs. The number is now 370 gardens and rising, and seemingly everyone in this city knows about and cares about Monarchs.

I want to live in a city that loves bats and loves butterflies. This is a pretty good measure of a successful city—and a pretty good way for us to foster hope and wonder and flourishing in an age of despair.

about the writer

Paul Downton

Writer, architect, urban evolutionary, founding convener of Urban Ecology Australia and a recognised ‘ecocity pioneer’. Paul has championed ecological cities for years but has become disenchanted with how such a beautiful concept can be perverted and misinterpreted – ‘Neom’ anyone? Paul is nevertheless working on an artistic/publishing project with the working title ‘The Wild Cities’ coming soon to a crowd-funding site near you!

Paul Downton

When I look at goals and targets for biophilic cities, I find that my concerns don’t lie with issues of design so much as values, social organisation, and culture. For instance:

- Does the city environment encourage or discourage awareness of non-human nature?

- Does the city demonstrate its connection with the life of its supporting hinterland/region?

- Does the management and operation of the city (read “urban system”) protect and celebrate the living systems on which it depends or otherwise connects?

- What is the status of non-humans in the city? Do non-humans have legal rights; are they protected in law? Are their lives valued?

- Are there penalties for damaging living systems? (I’m not keen on penalties, personally, but they seem to be an essential part of organised human society and if there are penalties for harming humans there must, in a biophilic city, be penalties for harming non-humans).

- Who represents the interests of nature? Can we consult with non-human species?

In 1988, John Seed proposed a “Council of All Beings” as a way for representatives of non-humans to be given an opportunity to put their views in a general council. Strip away the countercultural trappings of feel-good rituals and it is essentially role-playing, but it’s as good a means as any for incorporating the interests of non-human nature in a formal framework.

If our innate love for, attachment to, and need for nature has to be reduced to a financial equation to justify itself, then we’re missing the point of biophilia.

Adapted to a more mainstream, science-based footing, it is possible to see how informed human representatives could present the ecological needs of their adopted species, and that they might be ideal candidates for helping to shape biophilic city goals. What could be more genuinely biophilic than letting nature speak for itself about what is beautiful?

- Is it beautiful?

Beauty is measurable to some extent in fractal dimensions (Downton et al. 2016). People respond positively to images of nature but non-living and virtual fractal imagery score highly, and that is a conundrum any biophilic city goals must address.

Translating biophilia into something “actionable” in the city is a challenging idea once you accept that, measurable fractality or not, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”; even something that measures up well in terms of fractal geometry may not be universally regarded as beautiful. Writing about “The Divine Proportion”, H. E. Huntley quotes Sir Francis Younghusband, musing on the beauty of Kashmir scenery: “It is only a century ago that mountains were looked upon as hideous” (Huntley 1970 p. 89). Those “hideous mountains” are the same magnificent mountains as the modern ones (give or take a bit of snow cover and glacier extent), but there has been a cultural shift. People tend to see as ugly things that they find threatening. In Western culture, for instance, men with long hair have been seen as both fabulous and threatening.

- Is it useful? What’s it worth?

Beware measures of mere utility that “justify” the role of nature in the human universe by showing how it provides services to our species. That is not biophilia, and one can despise that which does you good service or serves you well. Biophilia is about the love of nature, not its financial reckoning. If you love a flower more because it is suddenly worth a lot of money, it is not the love of nature that is driving your passion, but a base desire for filthy lucre.

At one end of the spectrum, the appreciation of nature is driven by emotion. Here, nature is enjoyed at a visceral level for its perceived emotional, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits. At the other end of the spectrum, nature is valued for its utilitarian benefits as a service provider, e.g., as an agency for cleaning the air and water. On the face of it, it is easier to demonstrate the value of nature to urban populations by demonstrating that it is worth money, i.e., that it provides, or saves, thousands or millions of dollars in servicing costs. But the monetary system is a completely human invention with no basis in objective reality. Every aspect of the financial system is a fantasy and can change on a whim or overnight—literally. Billions of dollars rocket around the planet daily, but they have no existence outside of the shared (and enforced) cultural assumptions that equate bits and bytes to dollars and cents.

Natural systems, on the other hand, are real. They are healthy or not, they work or not, they live or die whatever we want to call them and regardless of what price we put on them. Hideous mountains probably offended early American pioneers because they were massive impediments to their push westwards. Mountaintops have been blasted to smithereens because human value systems could convert them into millions of dollars—they were worth more as rubble than as the abiotic base for a living ecosystem. The shared human belief in a magical financial system has proven, time and time again, to be stronger than concerns about damaging nature. The attribution of monetary value to nature is part of the same fiction that allows for the idea of endless growth on a finite planet. It is intrinsically flawed and, given the inter-relationship between money and politics, politically unstable and ill-suited as part of any measure of biophilia.

So, beware of what numbers “mean”. But in drafting our goals, we cannot rely on assumptions about the meaning of language, either. It does not remain stable or inviolate. It is a human creation and subject to all the vagaries and inconsistencies that implies. It changes as the central concerns of society change. I have written before about how the buttercup and another four dozen words relating to nature and the countryside have been redacted from the Oxford Junior Dictionary in favour of computer terminology like “broadband” that the dictionary’s editors decided was more “relevant” to modern children.

If it is necessary to be pragmatic in order to value nature in a way that can be converted into goals, then that pragmatism must be about recognition of intrinsic value as a part of what it means to be human. Because biophilia is about loving nature and the visceral/utilitarian spectrum is about appreciating nature, it might be concluded that goals for biophilic cities should “strike a balance” and include both kinds of evaluation of nature’s worth. But in some ways, that would miss the point of biophilia. If our innate love for, attachment to, and need for nature has to be reduced to a financial equation to justify itself in the human constructed environments of our cities, then maybe we’re losing the plot. Innate love fits with intrinsic value. One of the primary purposes of architecture and design in human settlement is to make places that please the human spirit, sensibility, and aesthetic sense. Disagreement about what exactly constitutes beauty does not diminish the value of pursuing it, and diversity of expression and response is part of the dialogue of culture. Loving nature for what it is should be enough, and if it isn’t, then there is a deep flaw in our culture.

References

Downton, PF, DS Jones & J Zeunert 2016, Creating Healthy Places: Railway Stations, Biophilic Design and the Melbourne Metro Rail Project. Docklands, Melbourne: Melbourne Metro Rail Authority

Huntley, HE 1970, The Divine Proportion: A Study in Mathematical Beauty. Dover Publications, New York

about the writer

Pippin Anderson

Pippin Anderson, a lecturer at the University of Cape Town, is an African urban ecologist who enjoys the untidiness of cities where society and nature must thrive together. FULL BIO

Pippin Anderson

I love the idea of biophilia—that, deep down inside, we all yearn for nature, we have an innate affinity for other living beings, and that we seek to connect with these living beings. In the same breath, we also know that part of the process of settling and growing cities is “making benign”, nature-safe spaces that can be easily lived in. I live in Cape Town, and while I am a strong advocate of more nature in and around the City, I also don’t want to dodge lions when I pop out for a bottle of milk or a newspaper at the corner café. I have had students from other cities in Africa describe to me how liberating it is to come to Cape Town to study and to be in a city without the constant threat of malaria.

Perhaps what we really want is to save biophilia as a human condition—and the most important metric is whether citizens of the city still feel connected to nature.

Real, unattended nature can be a challenging thing to live with. It seems, perhaps, as part of our urbanizing personas, we might have lost sight of some of the significant trials that nature poses to comfortable and easy living. We also know from research on nature in cities that the kind of nature people want varies considerably. Some yearn for a true sense of wilderness, with exposure to untamed patches of remnant nature, while others want facilitated nature with boardwalks, benches, and reasonably placed parking lots. So when we say we want biophilic cities, do we really know what we want?

Perhaps what we really want is to save biophilia itself

There is mounting research demonstrating people’s needs for nature, and even more evidence for broader societal needs in cities in terms of ecosystem service delivery, resilience, sustainability, and generally keeping the show on the road. We know, without a shadow of doubt, that we need nature. But not everyone knows that, and perhaps we (those of us in the know) feel that if we can keep this notion of biophilia alive, then we can use it to meet broader environmental and nature-related needs in cities.

So perhaps what we really want is to save biophilia as a human condition. Perhaps what scares us is the emerging idea of extinction of experience and constantly reduced exposure to nature; we fear the death of biophilia. We fear the generation that will lead without this biophilic dimension in them. We fear that we will somehow manage to let biophilia—and nature—go, live without it, to not even notice when the last vista goes under for a complex of high-rise buildings. I propose what we really want is to ensure that this notion of “biophilia” is kept alive in all of us.

So the metric of success becomes biophilia itself—and the people who engender this notion. Of course, to achieve that, we need nature in cities.

What we need is to be in schools, and out in society, asking the kinds of questions that get to the heart of whether people still have this biophilic feeling. While we must, of course, continue to secure green parklands and remnant patches of vegetation growing wild in our cities, and continue to strive to expose our populace to these features, what we need to keep an eye on in terms of success is whether people have the love of nature required to continue to fight for its existence. I think the exposure to nature needed to maintain the biophilic feeling is extensive and varied, both for individuals and to capture the extremes of society as well. In this way, I believe that the measure of a biophilic city can be found in its people. I am no social scientist, so I offer no exact metrics of how you go out there and measure biophilia, but I believe that is the correct metric to measure success.

All cities differ, and people differ, and how old or how young a city is, as well as the settlement history of its people, will all inform their views of and love of nature. The kind of nature they want; what they want to do with it; and when and where they want to do it, will all be informed by these different elements. For this reason, I don’t believe there is a single answer to what a biophilic city should look like. I believe it is a question of being in tune with the residents of the city, ensuring that they are exposed to enough of the right kind of nature, the kind of nature they desire, packaged in a form that pleases them, that will give rise to biophilic cities.

That is: cities full of biophilic citizens.

about the writer

Bram Gunther

Bram Gunther, former Chief of Forestry, Horticulture, and Natural Resources for NYC Parks, is Co-founder of the Natural Areas Conservancy and sits on their board. A Fellow at The Nature of Cities, and a business partner at Plan it Wild, he just finished a novel about life in the age of climate change in NYC 2050.

Bram Gunther and Eric Sanderson

“New Yorkers need and have rights to a local environment that is healthy and whole . . . such rights are essential to each individual as part of the community of nature as a whole.”

This quote, from the Declaration of Rights to New York City Nature is the living, beating heart of our efforts to establish nature goals for New York City.

Making New York City a leader in biophilia requires refining recently established goals into targets that can motivate policy and action.

Hosted by the Natural Areas Conservancy (NAC) and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), approximately 35 representatives from public, non-profit, and academic institutions have worked for two years to establish goals for New York City nature out to 2050. Through discussions, we came to consensus around the following five functional goals. Functions express what we want nature to do.

By 2050 the nature of New York City should:

- Provide living environments for species (Biodiversity/habitat)

- Mitigate damages from coastal storms (Coastal protection)

- Absorb and filter water from runoff and clean our air (Air and water quality)

- Enable movement of species through the city (Connectivity)

- Encourage human creativity and appreciation of beauty (Inspiration)

How will the nature of New York City provide these functions? Through the composition of nature we seek now through 2050. Composition provides the structures to do nature’s work in the city. We came to agreement that New York City nature needs us to:

- Conserve and restore nature’s communities (Native ecosystems)

- Encourage a diversity of species to keep ecosystems vibrant (Native species)

- Support genetic variety to help local populations thrive and adapt (Native genes)

- Make nature locally available to New York City residents (Access)

- Plan for nature along with the built environment (Integration)

- Enrich people’s lives and communities through active participation (Engagement)

To date, we have consensus among a subset of the New York City biodiversity conservation community that these functional and compositional goals reflect a broad spectrum of aspirations. Leaders from the non-profit organizations; city, state, and federal government; and academia, all see that this kind of large structure can help coordinate our actions and directions constructively, while still enabling freedom of action and initiative.

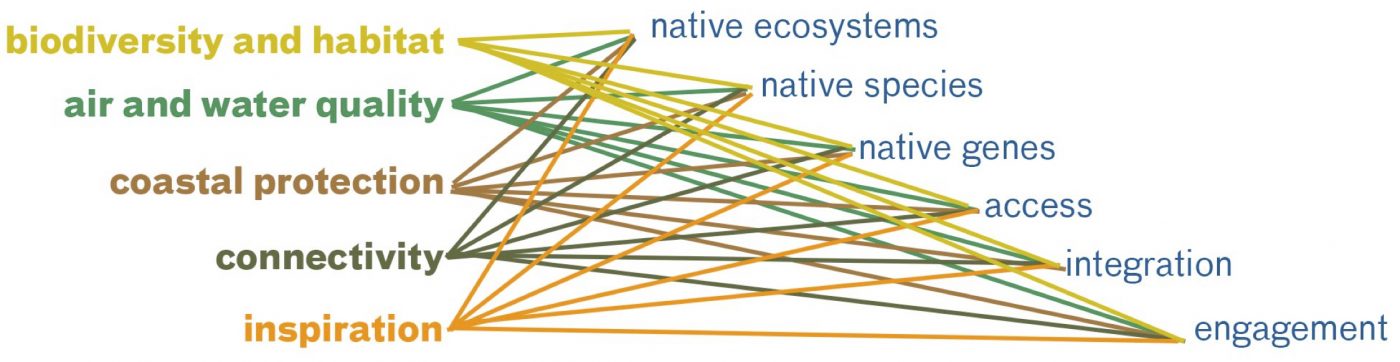

The real trick is to refine these goals into targets that can motivate policy and action, while maintaining consensus and alignment. Essentially, what we need to figure out together is how the different compositional elements of New York City nature satisfy the functions we outlined. In other words, how do native species contribute to coastal protection? How do ecosystems provide inspiration? How does engagement lead to biodiversity and habitat? Answering these questions—depicted the image below—lays the basis for setting specific, actionable targets between now and 2050.

We are working toward nature goal targets through a call and response structure in Phase II of the nature goal process. We have convened a large plenary group (approximately 75 people) of nature managers, academic scientists, urban planners, biodiversity conservationists, and advocates for environmental justice. About 30 of these people have volunteered for two working groups, one focused on ecological dimensions of the compositional elements of ecosystems, species, and genes; the other focusing on cultural dimensions of the elements of access, integration, and engagement. The working groups will propose targets for the plenary group to respond to; the working groups will revise and re-present. Through a set of four plenary and three working group sessions, we hope to find consensus across our minds and hearts and forge a consortium of organizations that will work to make New York a leader among biophillic cities. We propose to complete this work by 2018.

What comes next? In the third and final phase of nature goals, we plan to see concerted work to move the targets we establish into public and private sector practice; to establish a long-term funding mechanism for nature conservation and restoration in New York City; and to build a coalition and alliance of organizations and individuals to advocate for nature goals through the middle of the century. In part, we will accomplish all three of these through open community-based forums and workshops.

This initiative has been co-organized by the NAC and WCS and funded by the J.M. Kaplan Foundation. The NAC is a New York City-based conservation organization focused on the restoration and protection of the city’s over 20,000 acres of forest and wetlands. NAC programs are based on a belief in information-driven land management and coalition building as a means to sustainability. The WCS was founded in 1895 as the New York Zoological Society with the dual mission of helping New Yorkers connect with wildlife and to help conserve the places wildlife need. Today, WCS works to conserve wildlife and wild places in more than 60 countries in Asia, Africa, the Americas, and the Oceans, manages the largest network of urban zoological parks in the world, including the Bronx Zoo and the New York Aquarium, and connects urban people to nature through investigations of the historical ecology of cities.

[second_bio]about the writer

Eric Sanderson

Eric Sanderson is Vice President for Urban Conservation at the New York Botanical Garden, and the author of Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City. His upcoming book, Before New York: An Atlas and Gazetteer, will be released in 2026.

about the writer

Peter Newman

Peter Newman is the Professor of Sustainability at Curtin University in Perth, Australia. He has written 19 books and over 300 papers on sustainable cities.

Peter Newman

A Biophilic Parable

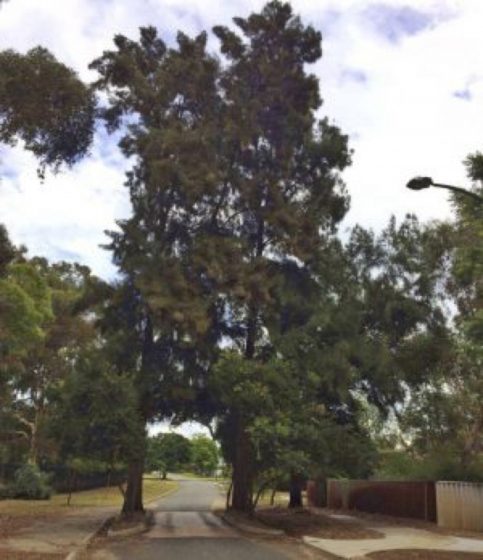

A recent article in a local online newspaper in Perth seemed very symbolic of the point biophilic urbanism has reached here in Australia, and perhaps elsewhere. It was a fight between some locals trying to preserve two large trees that were much loved but which were “lifting curbing” on the road.

Biophilic urbanism is part of post-modernism, which has more potential to be sustainable and resilient because it enables local solutions.

As the photos below show, the two mature trees, described as “local icons”, are relics of a time when the road was quite narrow and so they have become a traffic hazard. In reality, they are not a hazard, as they slow down cars, which must go through the gap one at a time, rather than in two lanes. What offends the traffic engineers and planners is that it is very messy.

Nature has a way of making cities messy. The biophilic urbanism movement is about making nature a part of our everyday life and, so far, this mostly means neat proposals for green roofs; green walls; green balconies; reclaimed streets; and parks and waterways with functional but natural systems. We often argue that the natural systems are just as good or better than engineered systems. But I think we should expect it to be messier than engineers want.

Neat cities are the result of modernism, which has detailed manuals for each profession on what is the single “best” way to plan and build infrastructure, buildings, landscape, economies, and even communities. As we move towards biophilic urbanism, we should see that it is part of post-modernism, which has more capacity to be sustainable and resilient because it enables local solutions, rather than just the simplistic single “best” ways of modernist professions.

Biophilic urbanism will be much messier.

The two trees in Perth were granted a last-minute, temporary rescue from the woodchipper after pleas from residents to find another solution. The residents are very attached to the trees and like what they do to the street in terms of landscape, but also in terms of traffic.

The local government wrote to residents to say it did not usually support the removal of trees but in this case it had no choice because the trees were “damaging infrastructure”. It also said they would not be replaced because there was a lack of space for new trees: “The City has plans for infrastructure upgrades to the traffic management devices in the street next financial year (subject to budget) which our engineers believe will require their removal.”

One of the residents said, “I am no greenie. I am involved in mining, but there are black cockatoos that spend a lot of time in those trees. The slow point is a key point as traffic is on the increase”.

I was asked to comment and said that trees slowing cars down was a worthy concept:

“The trees look beautiful and many suburbs would welcome such large specimens with canopies so attractive to bird life…I think the cars will be able to manage their way through. In my view the future of cities is to plant many more trees like these and create much more biophilic urbanism that people love…They need nature in their everyday life.”

We need to accept messy if we are to make a biophilic city.

about the writer

Chris Ives

Chris Ives takes an interdisciplinary approach to studying sustainability and environmental management challenges. He is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography at the University of Nottingham.

Chris Ives

The literal meaning of biophilia is affinity or love for nature. In this context, discussion of what constitutes a “biophilic city” and what meaningful targets may be must engage social and cultural dimensions as much as ecological ones. Certainly, targets must incorporate assessment of biophilic “elements” of cities (e.g., trees, parks, green roofs). But targets need to also account for the diverse values, perspectives, and preferences of people who live in and visit cities. These social and cultural factors are essential to understanding the degree to which biophysical elements of cities influence the human experience of urban environments. But how can these be assessed and incorporated with ecological evidence?

I don’t believe a biophilic city can be prescribed by metrics and figures. However, gathering data can be useful for understanding whether a city is heading in the right direction.

An important first step in pursuing this question is to stop and reflect on what is the ultimate goal of a “biophilic city”. Timothy Beatley defined a biophilic city as:

“a city that puts nature first in its design, planning and management; it recognises the essential need for daily human contact with nature as well as the many environmental and economic values provided by nature and natural systems” (Beatley, 2010: 45)

In this way, we see that the goal of biophilic cities is multifaceted. They are “nature first” (i.e., promoting ecological health), but biophilic cities also emphasise human interactions with nature. Developing targets for biophilic cities must therefore consider both ecology and people. I also suggest that rather than adopting a “standards approach” to developing targets, a “needs” or “values” based approach should be pursued. So rather than adopting a universal goal (e.g. a proportion of the landscape under tree canopy cover), targets should be developed that reflect context-specific demands.

A recent study by my colleagues and me on values for green spaces in Australia may provide some guidance in this direction. We assessed how urban residents assigned values to their local parks and reserves by engaging them in a participatory mapping exercise. We found that people assigned a range of different values to green spaces, including aesthetic, activity, and cultural values. We also found that these values were related to the design of the green spaces and their position in the landscape: for example the amount of vegetation cover in a green space and the distance of the space from a water body all had an effect on how people valued it. Further, analysis of socio-demographic data also showed that different types of values were more important to some residents than others. This research revealed what was important to the local community, and which areas of the landscape were underappreciated and in need of further management attention. Such data can feed into targets and goals for biophilic cities.

To really get to the heart of biophilia—affinity for nature—there is also a need to move beyond instrumental and functional values of green spaces and natural features in cities. While much attention has been paid to the health benefits and ecosystem services provided by green infrastructure, there is a risk that this framing does not capture the depth of the human experience of nature. Urban forests can be sites of mystery and intrigue—a reminder of a world that is bigger than us. Indeed, it is often the less-managed spaces that harbour the greatest biological diversity, yet also prompt ambivalent feelings of awe and fear. Human spirituality is also commonly intertwined with experiences of the natural world. Sometimes, it is the places that are least commonly visited that hint at a dimension of transcendence, that provide the space for reflection away from the congregating masses in shopping malls and busy streets. Undoubtedly, these kinds of experiences of nature are the hardest to translate into goals and indicators. Yet, surely, they must also be part of what constitutes a biophilic city.

I don’t believe a biophilic city can be prescribed by metrics and figures. However, quantitative and qualitative data can be useful in generating targets and indicators that act as signposts that signal whether a city is heading in the right direction. These must necessarily be designed in a way that reflects the unique character of the city. Below are four domains for which data may usefully be pursued in the interest of developing such indicators:

- Physical design: What places exist that provide opportunities for nature to flourish and opportunities for people to experience a diversity of ecosystems? What elements of biodiversity are especially important that need protecting and enhancing?

- Human behaviour: How do city residents use green spaces and interact with nature? Is there evidence of “nature routines” as part of a regular lifestyle?

- Human values: How important to residents is urban nature, and for what reasons? Are there particular places that are more meaningful than others? Do city residents consider nature to be part of their personal or collective identity?

- Governance: What formal and informal institutions exist for the management of biodiversity? How do decision-makers and government practitioners seek to enhance nature within the city, and promote residents’ appreciation of it?

Generating data around these four themes could be a useful way of developing indicators of biophilic design appropriate to each city’s context.

about the writer

Ken Yeang

Dr. Ken Yeang is an architect, planner, and ecologist. The Guardian newspaper named him as one of 50 individuals who could save the planet.

Ken Yeang

Many refer to the contemporary city as an “ecosystem,” but the contemporary city is not an ecosystem, nor is it ecosystem-like. The contemporary city is mostly inorganic. It is denatured, ecologically inert, and lacks the key attributes of the ecosystem that would enable it to biointegrate seamlessly and benignly with the ecosystems and the biogeochemical cycles in the biosphere. The existing city is, in effect, parasitic on the planet for its energy and material resources for its sustenance, and it gives nothing biologically beneficial back to the natural environment.

Instead of focussing on the biophilia of cities, we should be focusing on making cities into constructed ecosystems that are proxies and extensions of naturally-occurring ecosystems.

The existing city has an incomplete biotic-abiotic biological structure, unlike the naturally occurring ecosystems in nature. The existing city is unable to assimilate the emissions from the built environment’s production systems within the resilience and carrying capacities of the ecosystems in its surrounding bioregion and hinterland.

The land which has been fragmented for building the city remains disconnected, with poor ecological nexus, disrupting species interaction and mobility.

While greening the built environment as motivated by biophilia is good for the environment, it must not just take the form of undiscerning inclusion of organic mass. For example, the biotic mass must have non-invasive species. The species need to be native and their inclusion must come in the context of landscape conditions that must be designed to become habitats that will enhance overall biodiversity of the locality.

Biophilia is essentially an anthropocentric proposition, whereas we should be seeking nature-centric physical and systemic solutions. Nature-centric solutions seek to find ways to make our cities, our built environments, and our production systems (i.e. those systems producing energy, artefacts, and food) to be seamlessly and benignly biointegrated with the ecosystms and with the biogeochemical cycles in the biosphere. Instead of focussing on the biophilia of cities, we should be focussing on making cities into constructed ecosystems that are proxies and extensions of naturally-occurring ecosystems.

about the writer

Tania Katzschner

Tania Katzschner is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of City & Regional Planning at the School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics, University of Cape Town.

Tania Katzschner

In 2017, we are on the cusp of radical changes for our living world, culture, economy, and society. Our world is undergoing the largest wave of urban growth in history, and the city is thus one of the strategic sites where most of the questions about environmental sustainability become visible and concrete. Engaging with the problems we face in the world today requires a new understanding of our “sustainability dilemma” and reworking sustainability from modernism, so as to accommodate a better sensibility of dynamic complexity and aliveness.

Creating sancturaries for presence—being present in the world—could help us reclaim and recognise that we ARE the environment.

Civilization largely operates as if reality is about organizing inert, dead matter in efficient ways. The current ideology of dead matter, mechanical causality, and the exclusion of experience from descriptions of reality in ecology and economy are responsible for our failure to protect aliveness in our world (Weber and Kurt, 2017) [1].

It is impossible to build and sustain a life-fostering, flourishing, and enlivened society, or the “biophilic city”, with our prevailing “operating system” for economics, politics, and culture and within an anthropocentric mindset. It seems that we are abstracted, inattentive, and preoccupied rather than present to our surroundings—the living world we inhabit so carelessly. One can argue that human beings have become unearthed, distracted, dislocated, and resoundingly separate, and that our cities and our inhabitants need to come alive again.

I am an urban planner, which has a history of viewing cities as separate from nature. The urban is understood both in human exceptionalist and urban exceptionalist terms. This kind of thinking regards cities as places that have somehow risen above the biophysical constraints of nature. We foreground ourselves and our artefacts rather than the living world we belong to. The dominant attitude is one of doing what we want when we want, such as demanding strawberries for Christmas or avocados all year round.

There are many unconscious and unacknowledged precepts in current dominant thinking through which we see the world—such as linearity, causality, predictability, identity through separation, replicability, inertia, search for material causes, and explanation. One could say we largely live on rather than in the land, and we use and exploit rather than appreciate. This is a relationship with the landscape of “non-place”, where all is the same (Auge, 1995) [2].

To move towards “biophilic cities”, we need to wake up to connections and reestablish ties in a world of structural blindness. It is vital to discover a different form of thinking and to cultivate a living understanding of the spirit or power of the place, living connections and understandings of a place. I would argue that it is vital to create sacred spaces in our cities as sanctuaries for presence and sanctuaries for cultivating an open mind and openness every day, much like a child encounters the world without knowing. We need spaces that offer reprieve and the possibility of spiritual and imaginative recovery, reverence, and reconnection. Honouring the biological realities of Homo sapiens means acknowledging that we are completely dependent on our ecological systems. Creating sanctuaries for presence could help us reclaim and recognise that we are the environment.

Human beings are sentient creatures, yet over the last hundred years, human beings have increasingly lost the ability to be in touch because we have focused primarly on our intellect. When we observe the world of things, the world of stasis, we observe from the outside and our observing is instrumental. Too much appears discovered, disclosed, noted and listed.

Yet our world is not at all finished and given, but is changing, metamorphising, coming alive through the relationship between ourselves and itself all the time. Biophilic cities need to enable a moving beyond the borders of the known so that place can be intimately known, recognised, understood, and truly inhabited.

Targets and goals for biophilic cities need to move beyond the quantifiable and visible objectives to more indirect objectives, which can be much grander in forging ties and building enduring responsibilty. The story of the fox in Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s The Little Prince (1946) illustrates this well. In order for the little prince to get to know and tame the fox, they need to build a relationship and ties with patience over time. It is not about one being overpowering another or ownership, but about building connection, intimacy, and responsibility.

The Standing Rock resistance similarly depicts the significance of indirect objectives, which are so valuable when thinking about targets for biophilic cities. I have watched the unprecedented Standing Rock resistance with incredible excitement. Although the immediate objectives were not met—the camp is now evicted and the pipeline will almost certainly be built—it represents something so much bigger. It represents a coming together like we haven’t seen and something else is being forged in that. There are ripples of moral action, which feed a sense of possibility. There is no knowing what Standing Rock will do, but it may well set precedents for hundreds of years and contribute to changing our story because it engaged many sensibilities, head and heart, perception, intuition, feeling and imagination. In this way it also shifted and changed all that it touched. In working towards biophilic cities, we need to focus on cultivating healthy forces, connections, and relationships more so than only healing what we perceive as broken systems.

[1] Weber, Andreas and Hildegard Kurt (2017) The Enlivenment Manifesto: Politics and Poetics in the Anthropocene, in Resilience

Available at:

[2] Auge, M (1995) Non-Places Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London: Verso Books.

about the writer

Phil Roös

Phil Roös is known internationally for his leading work in environmental design and sustainability on large scale infrastructure projects. He is an ecological systems-inspired architect, designer, planner, and strategist. He is also Senior Lecturer in Architecture – Environmental Design (Ecology & Sustainability) at the School of Architecture & Built Environment, Deakin University, Geelong, Australia.

Phil Roös

The danger is that “biophilic” and/or “biophilia” becomes a catch phrase, a new trend where there is no substance under the surface. Frustratingly, I have started to notice more and more articles in the media about projects where the practitioners in the design and planning professions unfittingly refer to biophilia, arbitrarily using the words biophilic design, biophilic urban design, biophilic architecture, biophilic landscaping, and even “inspired by nature”, amongst many others.

Because the biophilic effect is more than what we can see on the surface, our biophilic design agenda must include the characteristics of the complex order of living structures.

Upon further investigation, many of these city-based projects use nothing different from a standard landscape design, or the use of vegetation in an architectural or urban design as a means of incorporating “greenery” into the urban fabric. If uncritical use of the term continues, the concept of biophilia will be watered down (as with sustainability and green design) and we will end up with nothing more to show than superficially green, vegetated landscapes dispersed in the city mosaic; vertical green walls in public buildings; and landscaped gardens based on the aspirations of our clients and those in power. In this short contribution, I would like to raise importance of the inclusion of the integration of deep patterns in our city-making process to support the right metrics towards a biophilia-inspired and resilient future.

Biophilia is “the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms. Innate means hereditary, and hence, part of ultimate human nature” (Kellert & Wilson, 1993). My interpretation of this phrase is that we are nature. We are not above nature, we are not just part of nature, but we are part of the whole.

The concept of “the whole” (inclusive of everything) as written about by Christopher Alexander (1977), can be supported by the Gaia principle, in which we, as Homo sapiens, are one species amongst many others that interact with our organic and inorganic surroundings on Earth to form a synergistic, self-regulating, complex system that helps to maintain and perpetuate the conditions for life on the planet. It is this deeper connection to the organised complex order of abiotic and biotic systems that results in us being nature, being part of the whole.

To be part of the whole is not simply to reflect on the need to link aesthetic preferences alone, but rather indicates a deep connection to the geometric structures and patterns that occur in the form-making processes of the living systems of nature (Salingaros, 2012). This biophilic effect, an important part of our daily lives, can be divided in two parallels; one source of biophilia instinct derives from inherited memory due to evolution, the second source of biophilia derives from the biological structure of nature itself. This structure comprises the geometrical rules of biological forms, a language of patterns—in essence, the combination of geometrical properties and elements of landscapes embodied in the complex structures found within all living forms (Salingaros, 2012).

This narrative indicates to us that the biophilic effect is more than what we can see on the surface, that what we see on the surface is only a reflection of the complexity of living structures underneath.

Our biophilic design agenda thus need to include the characteristics of a complex order, the complexity of the traditional ornament structure (Salingaros, 2015), inclusive of the rules of living structures (Alexander, 2001-2005). Rules for how ornament structure contributes to a healing environment can be derived from understanding how our brain is wired to respond to our surroundings. These rules are patterns. Our daily activities are organised around natural rhythms embedded within nature’s cycles. Patterns in time are also essential to human intellectual development, recognising the periodic natural phenomena such as seasons, annual events, and their effects.

Based on these rules of patterns, Christopher Alexander (1977) introduced into the design and planning of our urban spaces the notion that patterns influence place settings and provide formations for “living structures” in an orderly way. This structure of order, with reoccurring outcomes based on empirical rules, encompass a list of 15 fundamental properties that link geomorphological sequences and patterns in nature with geometric living structures of the built environment (Alexander, 1977; 2001-2005).

Perhaps these empirical rules of nature are the metrics we need to apply to the discourse of biophilic cities. The goals and targets we set for our future cities must be based on the generative processes embedded in the geomorphological sequences of the complex structures in nature—in essence, the structures beneath the surface. The biophilic discourse is not just about the greenery of our cities, as we have clearly identified in this article that there is much more to biophilia than surface.

about the writer

David Goode

David Goode has over 40 years experience working in both central and local government in the UK and an international reputation for environmental projects, ranging from wetland conservation to urban sustainability.

David Goode

It is crucial to have a vision, and that vision needs to be big. When I was appointed to a new job in London as Senior Ecologist in 1982, we didn’t have the word biophilia, but I knew what I wanted: to promote nature at every opportunity throughout the capital. That meant working with a huge range of different disciplines, including planners, architects, landscape designers, civil engineers, and a host of others. For most of them an understanding of ecology was not part of their daily life, and for many, removing nature was much more familiar.

There is much we can learn from our biophilic successes. The target is to think big.