“Do you seek the highest, the greatest? The plant can teach you to do so. What it is without will of its own, that you should be with intent – that’s the point!”

—Friedrich Schiller

Some days ago, after giving a lecture in a west German city, I arrived back at my Berlin neighbourhood subway station and walked home. I dragged my baggage trolley after me, tired from the journey, with a certain numbness of having seen and thought and being told too much. Too much dispersion, too many other lives entwined with my own, and a creeping loss of clear perspective on what I truly needed. Slowly walking back, I tried to exclude the sounds of passing traffic and the faces of passing humans from my perception.It was not at all about city vs. nature, or human vs. technology. It was about the struggle between control, and obedience—and being, and needing.

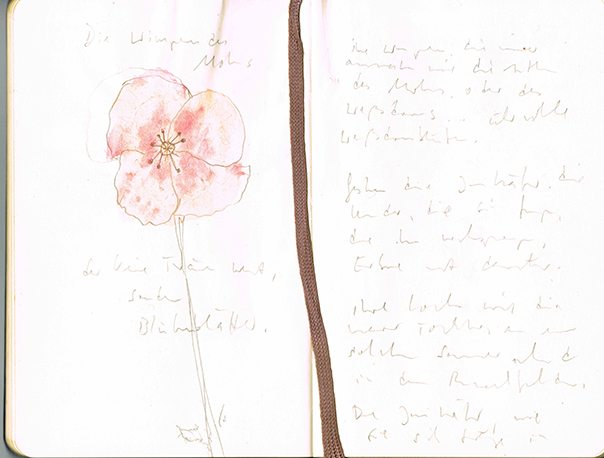

I was torn out of my numbness by a glowing red haze that hovered above a traffic island overgrown with herbs. At first, I only felt this: a sensation of something glowing, emanating warmth, literally palpable on my skin. I stopped and focused my gaze. There was a patch of vivid redness spreading in the middle of the streetscape with its hushed silhouettes of cars, passers-by, and cyclists. The colour seized my senses like a distant blaze.

I stood for some seconds and then I nodded. It was a tiny field of poppies. The blossoms of the common European field poppy (Papaver rhoeas) emerging from the small wasteland on top of the traffic island. As I stared at them, I could vaguely discern the single petals, shivering under the oblique sun. In a slight gust of wind the stems bowed, sending a wave that rippled through the glow. Some of the petals gently swirled to the ground. The blossoms seemed to burn away silently, flanked by the makeshift ecosystem of slender blades of grass, of mallow (Malva sylvestris) and broad-leafed sorrel (Rumex acetosa).

What is the essence of a city? What is the kernel of urban civilisation, which, as we know, is engulfing the planet? Urban life is spreading from a minority’s lifestyle to be the predominant fate of human and increasingly nonhuman beings. As I thought in a first glimpse, being stopped at that glowing traffic island, the essence of a city is a constant immersion of everything and everybody in human affairs.

And human affairs are affairs of control. They secure that we do not trespass norms, behave accordingly, function, are on time, cope with what is desired and what one increasingly is desiring—status, a beautiful face which does not show the traces of age and of any vulnerability. Traffic noise, anonymity, peak-hour hurry, traffic lights, cars rushing by with deadly speed are not “inhuman forces” destroying human naturalness. They are forces in service of control.

Urbaneness is a big experiment against the vulnerability that goes with life. At the same time, it generates more of it. More wounds. More fertile soil. Cities are not only the loci of efficiency, but also the places of failure. They gather poverty, breakdown, despair, crime—and unexpected solutions. They are meant to be run as machines, and they partly come out as alive. This is what always fascinates me, and what makes me cling to my home city, Berlin. Blossoms are drawn to a city, as there are always crevasses in the functional façade.

When I stood in the light of the poppies, halted in my tracks, the trolley handle-up on the street, and let my eyes sink into the flickering red rising into the air, I felt in the flowers’ precarious exuberance, the power of vulnerability unfold. In this vulnerability, the streetscape revealed itself as wild. It was not because a small piece of “nature“ was preserved, but because the poppies so adamantly insisted on displaying their vulnerability on this bit of casually neglected dirt. Glowing in the evening sun, they dwelled on their ramshackle settlement. It was a pledge for being whole even while under assault. It was a pledge of being whole not in spite of, but because of being vulnerable.

I was reluctant to carry on walking. The traffic rushed past me. My bag sat there, on the curb, as if it had been forgotten by someone anonymous. The evening sun warmed my hair and my body from behind. The poppies’ embraced me from in front. I was immersed in sweetness, and melancholy, and did not immediately understand why. I could not walk away.

Last summer, the poppies had been our company, when I was falling in love with a friend I had known for some time, but distantly. I looked for her at her place, which was in a tiny village in the Southern Alps, in Italy. We walked the fields among the vineyards, the evening air vibrating between us, with the glow of a light still hidden. It was the time of the poppies. Grasses and flowers freckled the side of the small road, but the poppies were in the middle. They stood there, glowing, and untouched, formed of slender, hairy stalks, and fluttering petals opened to the light. Their beauty called to us.

We walked there, feeling gifted by the flowers’ naturalness. Not by the fact, that they were “nature”, as we commonly say, but by their gesture of being totally, naturally, what they were. They completely believed in themselves. They surrendered to their fragility without reserve. “I don’t have that”, my friend said. “I do not have this softness.”

In this moment, I felt the desire to stroke her skin in the same manner as the blossoms stroked my gaze. I yearned to see her walk into some of that warm glow that emanates from beings who are openly needing what is truly needed. I wanted to kiss her, because the poppy had kissed me, had embraced me with its warmth that was total surrender, and I wanted my friend inside that embrace, too.

For a short time, the time of the poppies of last year, I forgot that we cannot grant this to another person. Only poppies can do it, as any other living being who does not know, but simply is, can. They love, because they totally surrender to their own fragility.

In Berlin, that evening, I could not resume walking home from the traffic island. My thoughts returned to the poppies of the year before. Each time, when I returned to Italy to see my lover, I was greeted by the poppies. They grew along the railway embankments, and between the tracks, welcoming my approach with their radiance and fragility. The blossoms risked themselves totally in their gesture to unfold, to be fertilized, to connect, to multiply. They knew dying was included in this.

I found the poppies everywhere in Italy; between the tangled steel lines of Milano Stazione Centrale, along ripening wheat fields, under greyish olive trees, beneath the umbrellas of maritime pines on the way to Rome, where we once met. I saw them in the crevasses of the streets in Roman living quarters. I spotted poppies emerging from the ruins along the antique Via Appia, where one endless afternoon we lay in a freshly harvested field.

Their blossoms watched us, and they allowed us to be fragile, as long as they watched us. They watched us by being fragile. They granted us space by basing their radiance on the fact that every petal only lasted for a few hours. When I tried to gather a bouquet for my friend once at her village, I came back with the stalks only. The fire could not be conserved.

The poppies were summer, but a summer as a pledge, still not totally and reliably there, a gesture of summer sweetness rather than its installation. It was like Natalie Babbitt writes in Tuck Everlasting of the early days of the hot season hanging at “the very top of summer, the top of the live-long year, like the highest seat of a Ferris wheel when it pauses in its turning. The weeks that come before are only a climb from balmy spring, and those that follow a drop to the chill of autumn…”. Our love was in the poppies, and when I think back, its sweetness is part of what the poppies did, rather than the other way round. When our love blossomed, a slight breath could extinguish it.

At some point, in Berlin, I walked on, dragging my trolley after me. It seemed to me that its wheels circled with smoother revolutions, in a more effortless way as when traveling to Italy in the previous year. I slowly walked towards my home, not numb anymore, but vulnerable, feeling all sorts of feelings, sweetness, and soreness, birth, and death. “Blender”, my lover had called the states of her unseparated, undiscernible emotions, when she was in them, that numbness I also had felt stepping out of the subway. But that was gone now, substituted by something clean, and melancholic. The poppy’s blossoms are a sort of centripetal agent. They help solidify feeling, as the slender flowers show what they need. There is no error possible in what makes them live, or die.

With the anesthesia gone, I gazed around on my short way back home. I returned the gaze of all the blossoms I encountered, growing from slits in the curb, from untended spots between the green stretches in front of the tenements, in the neglected yard around the building of the high school my son graduated from last year. I felt seen, and I felt allowed to feel. I could be, because all these others trusted their needs. I could trust mine. And in the slight afterglow of the poppy’s blossom everything settled into clarity. I started to blossom myself.

The poppies I encountered, now and last year, are not a feature of rural areas (rural like the sweet southern alpine landscape where my lover lived). They are not a feature of “nature”, which could awaken me and console me by the way it had found its path between the “human-made” landscape of the inner city of Berlin. It was not at all about city vs. nature, or human vs. technology. It was about the struggle between control, and obedience –– and being, and needing.

It was about what family psychologist Virgina Satir calls the “Five Truths”, which are about being genuine about what we need, and perceive, and want to do. The poppy grants itself the right to be real. By its nature, it has no choice. We can see this absence of choice as determinism, like mainstream science is inclined to do. The blossom as genetic machine, totally dead from the inside. But we can also see it as a fantastic intuition about the right thing to do. As self-confidence. As a statement, announced by a red glow, and hairy stalks, and total wastefulness, about a real individuality.

“I am what I am”, reads a famous line in the old testament. I never really appreciated this enigmatic phrase, beyond it being a bit tautological. But what the poppy tells me, and other city dwellers, is just that. I am what I am. And what my lover for those days of the poppies, last year, until all the petals had been blown off by our reluctant breath, was telling me again and again, was the opposite of this: “I am not what I am, and that makes me suffer.”

So, what we call nature, is not about being self-made (organic) against human-made (technological). It is about being oneself, making oneself from the powers of the flesh that yearns for unfolding, against not being oneself, enclosed by powers who tell me what to do, how to behave, what to feel, until I have completely forgotten what my powers are—forgotten the fact that I also long for blossoming. That, indeed, blossoming is what all beings not only want, but need: to become a manifestation of blossoming, as my friend and colleague Hildegart Kurt puts it.

One of the places to blossom is the city. We all know this. It’s the reason we constantly travel to cities, although we are yearning for “unspoiled nature” at the same time. Wild flowers in the city are not a contradiction, but one way a city blossoms, and hence also allow me to blossom. I am lucky that Berlin is full of flowers in summer, full of small wild spaces, sought by rare plants, and peopled by rare beasts.

Berlin is not the world’s poppy capital, though. That is Rome. Not the official beautiful Rome, but the dirty backdoor, hidden Rome, which you cross when approaching or leaving. It’s the Rome where I had stayed with my lover last year, for one short week, under an uncompromisingly blue sky. And when it was over, something was lost. It’s the Rome of the memories which grow not from idealizations, but from wildness, which has been watching us with tenderness and irony, and hence granted us to be wild for a couple of moments. Wild, here, does not mean unchained. It means self.

Self is a call. To see others blossom is a call. This explains the strange mixture of joy and longing I experience when I see other beings blossom. It shows me that I need to blossom, and it highlights for me the degree to which I already do. Or do not. Or can’t yet. The joy of the blossoms is a yearning.

There came a time, at the end of the season of the poppies, when my lover started to be wary of her vulnerability. She felt she had already shown too much of it to me. “It’s holes all over”, she said, feeling ashamed of herself. Of her individuality, which was beauty, in one individual making, from vulnerability, in one specific cast. Holes, like we all have, in her brilliant arrangement. Poppiness, ready to shed all the petals at one shy breath.

“Loving is touching souls” writes Joni Mitchell in her song “A Case of You”. This includes being allowed to be vulnerable, finally. That is why we are all searching for it, in the haze of the cities, among other single humans, hasty, lonely, very much in control. But love not only allows vulnerability, it also needs it. Loving is a call for vulnerability. A call like the poppies were uttering on the neglected island in the rushing Berlin traffic, which made me stop in my tracks, and let the wounds of the last year re-open, sweet and sore.

Love is a call for vulnerability. To let yourself be loved is to show all your vulnerability, because one who truly loves you wants you to be true. To be who you are. That’s the essence of it. And this is why the poppy is leading the way. It is encouraging us to be all we already are. It is a fundamental way of loving. The time of the poppies was over when my lover started to close herself, feeling too fractured, and I let the petals fall. We had lost our pact with the blossoms.

Andreas Weber

Berlin

References

References

Quoted according to Lorenzo Ravagli, “Live and Let Live”, Erziehungskunst (Waldorf Education Today), http://www.erziehungskunst.de/en/article/love/live-and-let-live/

Hildegard Kurt, Die neue Muse. Versuch über Zukunftsfähigkeit. Klein Jasedow: thinkOYA, 2017. See also https://cultures-of-enlivenment.org/en

Andreas has a new book coming in August 2017, called Matter & Desire.

Leave a Reply