One adage I want to share after finishing the US Forest Service Inaugural International Urban Forestry Seminar is: look more closely, think more deeply. This was something that one of the presenters said to us on our first day in Chicago and it stuck with me throughout our journey.

Collaboration is key and we need to listen to one another actively and globally to achieve common goals.

Given my eclectic academic and professional background, my view of urban forest management, research and planning has largely focused on Canadian needs and perspectives. The experience of this two-week seminar broadened my understanding of international viewpoints and directions with every site we visited by sharing outlooks on the challenges facing communities and greenspaces in urban environments. Although many of the sites overlapped themes, this only served to emphasize the complex integration of urban issues. The themes we dealt with at specific sites over the two weeks included:

- Environmental education (Seward Elementary);

- Resiliency and restoration (Gary, IN);

- Alternative education and community development (El Valor)

- Environmental justice (Faith in Place and Sacred Keepers)

- Building social, ecological and disaster resiliency (NYC Parks)

- Governance and community connectivity (STEW-MAP)

- Social and ecological restoration (Rockaways)

- Access, environmental education (Biobus)

- Activism and partnerships (Community Gardens)

- Community engagement, art and innovation (SWALE)

- Food justice and food security (Brooklyn Grange)

- Environmental stewardship and youth development (Rocking the Boat)

Our itinerary included a wide array of field trips, site visits and case studies to examine approaches, techniques, tools, and partnerships that showcase the overall theme of the seminar: Community Engagement—the underlying significance being that without community support, the natural (physical) environment we strive to conserve cannot be sustained. Through engaging discussions, presentations and experiential learning, we shared understandings about urban forest management, urban planning, and community engagement.

The seminar exceeded my expectations and afforded me an opportunity to experience a multitude of community activities and programs related to social and environmental justice. One of the main things that stuck out for me was the importance placed on the multi-level partnerships and the scale with which these relationships are imbedded. I am thankful to have met new and inspiring people from around the world. The primary lesson I take from this group is that collaboration is key and we need to listen to one another actively and globally to achieve common goals.

Prior to arriving, we were asked to identify questions and challenges to natural resource management and urban communities facing our countries. During the first few days, each participant offered an introductory presentation on urban forestry and community outreach issues in our home country, allowing us the opportunity to get to know one another more closely, to recognize the common challenges facing practitioners worldwide, and to find common (or dissimilar) entry points into critical dialogue.

From a Canadian perspective, the main questions I proposed were: (1) Given that some countries have competing (or other) priorities (e.g. poverty, political unrest), what are the motivations for engaging governments and communities in urban forest stewardship and education? (2) What are the considerations for being inclusive with respect to diverse cultures, ethnicities, religions, and economic backgrounds? Questions that my seminar colleagues offered included: What are the regulations for planting specific species in urban areas? How do you engage people that have limited access to education? How can we move away from science being an elitist activity or concept and make it accessible and fun? What are the similarities and differences among departments at different levels of government and how can we learn from one another to bridge gaps?

Overall, our collective challenges to urban natural resource management included: lack of awareness and urban forestry education programs; disconnect between research initiatives and applied practice; lack of policies incorporating urban greening in infrastructure; increased residential and commercial development; absence of strategic approaches at federal and regional levels; and lack of knowledge exchange between communities and across professions.

One of the main goals of the seminar was to enable and empower participants to ask questions about how we can develop, replicate and maintain similar programs around the world. Daily, the seminar left me considering the notion of responsibility and what we can do in our respective positions and countries to enhance community resilience and engagement in urban environmental sustainability. In my case, for Canada, one of my roles with Tree Canada, a national NGO dedicated to urban forestry, is to provide direction for the Canadian Urban Forest Network (CUFN) and Strategy (CUFS). Our national steering committee is currently in the process of updating the Strategy for the 2018-2023 term. We have an opportunity to move in a more socially inclusive direction by revising the five working groups of the Canadian Urban Forest Strategy to include critical operational elements that will benefit urban forest infrastructure. Specific activities organization-wide can include:

- To advocate for alternative modes of education and creative communications

- To better integrate citizen science and crowd-sourcing into our knowledge sharing and knowledge production work

- To incorporate more inclusive community engagement strategies for long-term volunteer commitment

- To actively broaden the multi-disciplinary Canadian Urban Forest Network and reach the audiences that are currently under-represented

- To determine and explore areas of collaboration with the US Forest Service to bring iTree and STEW-MAP into Canada

- To engage with the Canadian Forest Service as their primary external partner to help develop urban forest policies/mandates

In Tree Canada’s work with municipalities across Canada, communities have expressed that the primary challenge is a lack of federal support. The Canadian Forest Service is currently developing their internal mandates related to urban forestry; this new development in Canada’s federal government offers an opportunity for closer collaboration.

Lastly, even though diversity was not an overtly identified theme, it permeated every discussion and presentation we experienced. The contribution of women in urban forestry and arboriculture is the overarching narrative that I am currently examining in my postdoctoral research through the University of British Columbia. As such, it was particularly interesting to me that the majority of our host speakers were women. It was inspiring to see the influences of so many women at different ages and stages in their careers, not to mention the diversity in race, ethnicity and perspectives.

In order to better understand some of the questions being raised and the challenges with which we were contending, I want to share some of the places we visited during our seminar that best exemplified the major themes listed above.

The Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum: environmental education

Also known as the Chicago Institute of Science and Technology, the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum serves to bridge the gap between science and practice working with communities both on and off site. With both their live and dead specimen collections, the Nature Museum offers unique learning opportunities for students and the public with their summer camps, overnight and after school programming, and series of exhibits and events. This site was our home base for much of the Chicago portion of our journey. Our discussions here began with introductions to the seminar and the space as integrative gateway for access to nature and science knowledge. Set within Lincoln Park, the Museum serves as a model for environmental education facilities.

Seward Elementary School and Jardincito: environmental education and community engagement

At the Seward Elementary Communication Arts Academy we experienced how environmental education programs are brought directly to the classroom. Jo Santiago of the US Forest Service presented live raptor specimens and discussed habitat, behaviour, individual stories, and the lessons birds of prey can teach us about ourselves.

We also learned about engaging communities where they live at Jardincito in south Chicago with Carina Ruiz of the National Audubon Society. We discussed urban environmental stewardship and resiliency against challenges of poverty and gang violence. The takeaways here for me included bringing passion to our jobs and using non-traditional ways of learning and understanding how profoundly surrounding environments can impact student learning and development.

Gary, Indiana: resiliency and restoration; brownfields and reindustrialization

The visit to the Mayor’s office in Gary, Indiana, fostered discussion on how industry can often have such a deep impact on the social succession of a community—who was there, who came after and the impact on landscape use. With the continuing decline in population since the 1960s, 10,000 houses are currently abandoned. Brenda Scott-Henry, Director of Environmental Green Urbanism Affairs, and Deirdre Campbell, Director of Commerce explained that the City of Gary is working hard to stabilize neighbourhoods through community green infrastructure plans and programs like Universal Access at Marquette Park among others like nature tours and historical preservation tours.

During our tour of the surrounding neighbourhoods in Gary, I was struck by the long-term commitment of some of the volunteers who have settled in empty communities maintaining anywhere from three to six houses at a time. The City also encourages volunteers to paint decorative board-ups and fake windows during “blight” removal (blight: term used to describe building decay and illegal dumping). In addition, local and international artists come together each year for the Graffiti Art Festival as part of community building and beautification.

As we drove through the east side of Indiana, which is overwhelmed by the impact of its steel mills, the question we grappled with is what do you do with these spaces when the mills close down? This reminded me of the Ruhrgebiet, or Ruhr region, in Germany (cultural capital 2010), and the reindustrialization of Landschaftspark in Duisburg-Nord, for the purpose of tourism. While not at the same scale in Gary, however, the City’s efforts to restore the declining population and devastated landscape is ongoing. The takeaways here for me included understanding how to engage the local communities based on their immediate needs and create community ownership.

El Valor: alternative education and community development

El Valor, a non-profit social service agency with programs focused on engaging adults and children with cognitive and physical disabilities, serves communities mainly comprised of immigrant families, a majority of them from Mexico. Monarch butterfly symbolism is used as a cultural metaphor for migration and journeys. Integration of environmental art using cultural connections like “dia de los muertos” (a cultural celebration of our life cycle in remembrance of relatives) is a cornerstone of their program.

As a non-traditional partner, the El Valor children’s centre and programming supports 500 families to train families together. Parents are valued as their child’s first teacher; as such, much importance is place on family engagement in the knowledge sharing and learning process. It may be common to walk by a piece of artwork created by a child and not realize the complexity or the impact behind it. The takeaways here for me included a better understanding of using symbols as cultural connections for environmental education, that everyone is a stakeholder and can be involved in the process of conservation through creative pathways.

Faith in Place and Sacred Keepers Sustainability Lab: environmental justice

On our last afternoon in Chicago we had a panel discussion with Reverend Debbie Williams, Veronica Kyle, and Toni Anderson about environmental justice. I was moved by each speaker’s passion and intimate integration into the community. The question that this conversation raised is how do you have the uncomfortable, complicated dialogue about race and environment?

First, Veronica Kyle, Chicago Outreach Director for Faith in Place, spoke about engaging faith-based communities in developing green teams to deliver programs of environmental stewardship and conservation. Their mission is to reach diverse people of all faiths, races, ethnicities, and sexual orientations to share the commitment to care for the earth. She made a compelling argument to make room in operational budgets for diversity. She also spoke about overcoming the resistance to the message of environmental impact by meeting a community’s immediate needs (e.g. jobs). For example, if you have mold in your home, you are not going to care about geothermal solutions.

Second, Reverend Debbie Williams from Faith in Place spoke about story circles and the importance and power of narrative and storytelling in connecting people to people and people to nature. Encouraging leaders to be inclusive and listen to the priorities of communities and explore multiple avenues of entry into the environmental conservation conversation. “Fostering the family and people connections is key in environmental programs because people will do things for the love of one another.”

Finally, Toni Anderson of Sacred Keepers Sustainability Lab spoke about indigenous cultural connections to nature, youth engagement and the need to understand the importance of histories and legacies of ancestral land and settlement. This raised questions about equity, power and race and how these issues underlie land use and ownership and ultimately governance. The takeaway here for me included a better understanding of how to engage with groups who are often overlooked in the environmental science discourse.

NYC urban natural areas: building community resiliency (social, ecological and disaster resiliency)

Our first day in New York was spent discussing how we build, develop and maintain resiliency after disaster; the importance of public-private partnerships— how we develop them and leverage resources; and the balance of green and gray infrastructure. Land use management is a 3-way partnership in New York between the US Forest Service (who does not own any land in NYC), The Natural Areas Conservancy, and the NYC Parks Department. Bram Gunther, of the NYC Parks Department and Natural Areas Conservancy provided an overview of NYC’s natural areas and greenspaces, restoration, and green infrastructure.

Dr. Lindsay Campbell of the US Forest Service spoke about the important role of the Urban Field Station as a research base for studying the city as a social ecological system (integration of social and biophysical). This is done through adaptive management, applied science, and public-facing programs. The Urban Field Stations serve to create a space of meaning where people can be innovative and where new topics and ideas can emerge. In NYC, the importance is focused on forming interdisciplinary teams and operating as a network across the country. The takeaways for me here were the importance of people underlying land use management and their individual responsibilities for tree care.

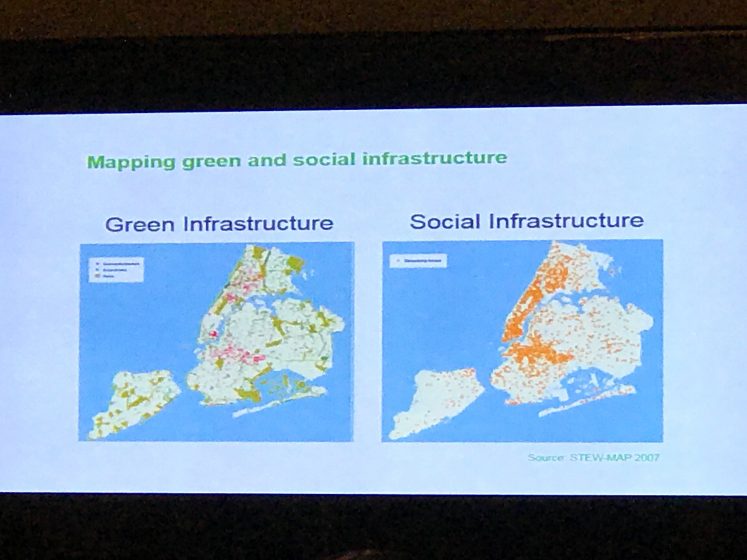

STEW-MAP and i-Tree Tools: governance and community connectivity

How do we understand the social, spatial and temporal interactions within a city of 9 million people? This is the research question that underlies the Stewardship Mapping and Assessment Project (STEW-MAP), a civic capacity map and a data-driven set of tools that has resulted in a regional list of 12,000 groups who steward the urban spaces across NYC. Drs. Michelle Johnson, Lindsay Campbell and Erika Svendsen explained that the tool itself is for natural resource managers, funders, policy makers, educators, stewardship groups and the public.

The tool collects information on organizational characteristics, physical geography and organization social networks (relationships). Maps and databases can be generated to better understand civic capacity and support community development.

On the application side, the benefit is building a community of data contributors who share the same goals for sustainability. With respect to governance, people can be positive agents of change; without stewardship groups, there is a high possibility that the landscape will not be sustained. The mapping provides a legitimacy of these groups. Stewardship and indicators of social resilience include: place attachment, collective identity, social cohesion, social networks and knowledge exchange.

In addition, Scott Maco of the Davey Institute spoke about i-Tree Tools as method for urban forest management and research. Analyzing the structure of the forest to garner present data that is relatable to a general audience and useful for proactive planning given its applications (e.g. i-Tree also measures health and vulnerability data). These tools are available for free.

Rockaways: resilience and ecological restoration

The Rockaway Institute for Sustainable Environment (RISE) is a community hub for artists, residents and scientists to congregate and collaborate on issues facing the Rockaway peninsula. At RISE we discussed disaster response, the impacts of Hurricane Sandy on the surrounding community and the efforts to plant native grasses to stabilize the dunes at Rockaway Beach.

Biobus/Biobase: access, environmental education

At the Lower East Side Girls Club in Alphabet City we were introduced to the Biobase and the Biobus, a mobile science lab that serves 150-200 elementary, middle and high school students on any given day, across 111 schools in 154 days per year. As students discover science through the Biobus, they have opportunities to explore their interests in more depth and then pursue after school programs. Dr. Ben Dubin-Thaler, founder of the Biobus, spoke to us about how the bus provides access to science knowledge and equipment and offers an alternative approach to environmental education.

Community gardens in NYC: activism and partnerships

We examined community gardens through the lens of activism, community partnerships, resiliency and public health with Aziz Dekhan, New York City Community Garden Coalition, and Charles Krezell from LUNGS (Loisada United Neighbourhood Gardens). We were introduced to the rich history of NYC community gardens and how they offer a refuge for communal gathering and contribution.

Some of the sites we visited were long-established gardens that the organizations had to fight the City (via litigation) to keep, due to threat of increased development. More broadly, many communities struggle with this challenge and can either grow closer in the process of standing together, or some projects can come undone in the face of overwhelming adversity.

SWALE: Community engagement, art and innovation, food security

Our visit to SWALE, New York City’s floating food forest, integrating permaculture, social design and art for education was innovative and inspiring. Founded by artist Mary Mattingly, this garden is built on a barge and travels to the various piers in NYC, serving as a mobile outdoor classroom to educate visitors about food security and stewardship of land and public waterways. This initiative addresses the challenge that many citizens live in food deserts (areas with limited access to fresh food). The correlation between public health and greenspaces is becoming more widely acknowledged and projects like SWALE are important models for public education. For me, this site captured many of the themes of that we dealt with during the overall trip: integration of nature and cities, community coming together, art and creativity, mobility and transformation.

Brooklyn Grange: food justice and food security

At Brooklyn Grange Rooftop Farm, we received a tour by founder Anastasia Cole Plakis, who spoke about the important role that urban agriculture plays in connecting communities to nature and getting people to think about where their food comes from on a broader scale. She spoke about the necessity of educating inner city youth about nutrition and how many of them do not think of the space as a farm so much as a park until they see the four chickens in their coop. The chickens are kept to connect the space with farming and food in the minds of schoolchildren who visit the rooftop. The cycle of this for-profit business involved growing food, selling it to local restaurants, and then using part of the profits to host education programs.

Rocking the Boat: environmental stewardship and youth development

Rocking the Boat, an organization that focuses on youth development and environmental stewardship through boat building, environmental science and sailing offered us a unique experience to row down the South Bronx river with youth educators as our guides. Their three core programs engage over 200 youth per year who move from being students to paid apprentices to alumni then to being eligible for part-time work with the organization as Program Assistants. Participants in the program also receive services from social workers and counselors who help them plan their long-term goals. Groups like this help youth to build strong foundations in environmental stewardship. Click here to hear from the team at Rocking the Boat.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the US Forest Service International Programs, for including Canada in this seminar, and I’m thankful to Tree Canada for recognizing the importance of this seminar and affording me the opportunity to attend; our work will certainly benefit from the insights garnered during this two-week journey.

The organization of this inaugural seminar was seamless due to the dedication of the coordinating team; a huge thank you to Kristin Corcoran, Mike Rizo, Liza Paqueo, Rachel Sheridan, and Pam Foster, for making our experience as comfortable and fun as it was informative and memorable. I look forward to future collaborations.

I’m also grateful to all the hosts of this seminar over the two-week period in both Chicago and New York. The shared insights are beneficial to my practical work and academic research; but I’m particularly grateful for the personal experiences this journey afforded, including:

- Getting out of my comfort zone on more than one occasion (e.g. speaking to 5th graders);

- Re-learning the meaning of acceptance by feeling humbled by the social interactions and level of compassion and commitment of volunteers;

- Being exposed to the challenges of urban forestry and social engagement from different countries around the world;

- Re-kindling my own passion for collaboration and knowledge that people can achieve anything if they’re kind, open and community-focused.

Finally, I’m grateful to my co-participants for their honesty and openness during our sessions while sharing stories and experiences. It was an honour to be part of this incredible group and I’m thankful for the opportunity to learn from, and contribute to our engaging discussions. After all, the best experiences are the ones that are shared with the people we meet along the way.

Adrina C. Bardekjian

Montreal

References

Click here to meet the 2017 participants of the inaugural US Forest Service International Urban Forestry Seminar.

For photos and videos, please visit: https://www.facebook.com/adrina.bardekjian/media_set?set=a.10159479025725377.1073741833.665320376&type=1&l=fdb192fec4

US Forest Service International Programs. 2017. Concept Note: 2017 International Seminar on Urban Forestry. Introductory document given to participants about the seminar.

Leave a Reply