Facing the ecological dilemma created by urban growth and climate events means moving from pilot projects to landscape-scale conservation.

To catch a glimpse of the wildlife that is returning to Greenway Park at Fanno Creek, take a peek at our “critter cam” video.

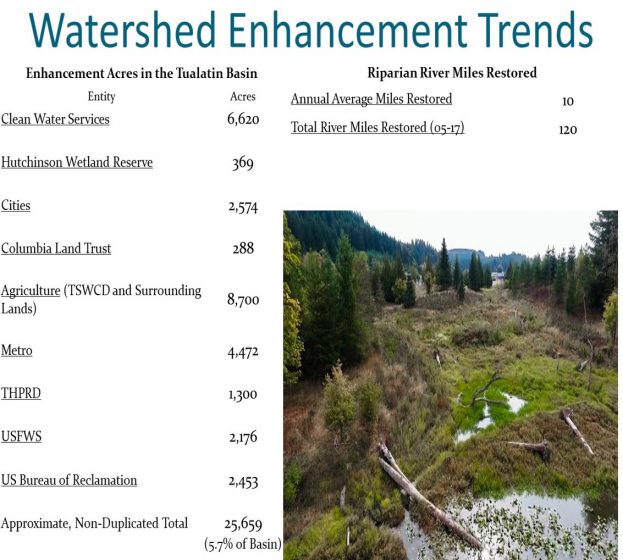

Tree for All is one of the USA’s largest and most successful landscape conservation programs. In the past 12 years, Tree for All has successfully restored over 120 river miles (10 plus river miles annually) across more than 25,000 acres in the rural and urban communities of Washington County, Oregon.

If you’re interested in learning more, check out this video about Tree for All partners and the tree planting challenge that started it all.

Common community vision: what’s good for Mother Nature is good for humans too

If others want to replicate the program, they need to understand that you have to get community buy-in to be successful. Tree For All is a collaborative effort that takes many jurisdictions. Folks from the public sectors, schools and others, they all have to buy into it.

— Andy Duyck, Washington County Commission Chair

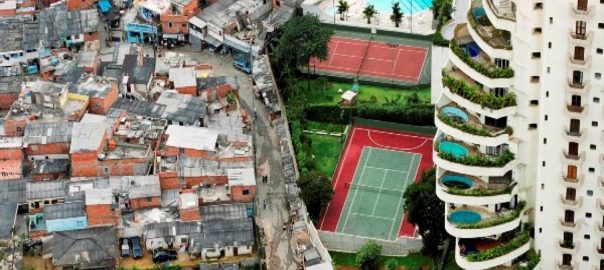

Our natural resources provide many benefits to humans, such as clean drinking water, healthy air, and nourishing foods. In addition, we require efficient transportation networks and cultural diversity to create resilient, thriving human communities. As we play witness to hundreds of restoration projects, it becomes clear that local wildlife has many similar needs. A grey squirrel needs a network of natural vegetation to provide food and transportation, allowing it to cross the watershed without ever touching the ground. Lacking such highways, that squirrel experiences the same dilemma as humans when we see a “road closed” sign with no detour.

These wildlife highways cross urban, rural, and forested landscapes where humans also reap great benefits from natural resources. Floodplains are an example of an ecosystem that provides a water highway for migratory birds, fish and other wildlife. The restoration of these “water highways” also benefit human communities by providing flood mitigation, carbon sequestration, water filtration, and recreational areas for activities such as fishing or boating.

In agricultural areas, clean air and water, healthy soil and pollinators propagate our human foods. Native plant buffers on agricultural land are an example of a way that communities can help wildlife and humans thrive. When we plant strips of native plants along water margins, they provide shade, slow runoff, and absorb nutrients from agricultural land. Just as humans need clean water, so do the fish and wildlife that greatly benefit from the water cleansing benefits of native plant buffers. Indeed, the benefits of native vegetation buffers—cleaner air and water, shade from the urban heat island effect—also extend to the children who walk along Fanno Creek observing egrets and Pacific tree frogs.

Time and time again we have found that if we help to restore native vegetation, Mother Nature is capable of doing the rest. When Mother Nature is given the opportunity to succeed, wildlife and human communities thrive together.

Partnerships: Working together, we each gain strength while enhancing community benefits

Tree for All is possible because of the partnerships that were established over the last ten years. That’s how you get a million plants into the ground. It took people reaching out and asking others to help—and by doing that, we now have this whole social system that revolves around getting this kind of work done.

— Carla Staedter, Environmental Coordinator, City of Tigard

A beaver pond creates an interesting partnership between the wildlife and native vegetation of Fanno Creek. Waterfowl find a welcoming home to raise their families when water is available and native vegetation helps create the habitat needed for turtles, songbirds and fish. Each of these creatures rely on each other to provide food, habitat and water, which puts in motion the makings of a healthy and vibrant watershed. However, this setting meets an interesting challenge when we consider the role humans can play in this story. This role can either be a controlling dictatorship, or, preferably, that of another watershed partner that finds nourishment in their association with local wildlife.

Like many words in the English language, the term “partnership” has many definitions. Tree For All has created its own definition that can best be told by a story about a stranded traveler with a flat tire on a hot dusty road in central Oregon.

A stranded traveler stands beside his car with tire iron in hand, a sweaty brow, and the dejected look of person missing a jack to change his flat tire. It’s not long, however, before a fellow traveler sees this situation and stops to help. With pen and paper in hand, he jumps out of his car to lend this troubled traveler a helping hand. He asks about the make, model, and gross weight of his car and quickly jots the information down. Turning to the troubled traveler, he quickly assures him that he will order a jack in the next town and have it sent back to him. Smiling, this Good Samaritan jumps back in his car and speeds away. He is happy knowing he helped a struggling traveler.

It’s not long before another helper stops to lend aid to the flat-stricken traveler by handing him a bottle of cold water. He smiles as he drives away, watching in his rearview mirror as the struggling traveler thirstily downs the bottle of water. He feels good that he was able to help.

The next traveler is a different character. He is the owner of the local drive-in a few miles back, and every weekend he makes a strawberry milkshake and takes a leisurely drive in the country with the top down on his convertible. Seeing the same situation as the previous travelers, he also stops to lend aid. He hands the weary traveler his milkshake and tells him to drink and sit in the shade while he gathers the jack from his convertible and changes the tire.

When I think about creating great partnerships, they begin with a kind gesture and an offer to meet and exceed expectations. In this story, both travelers reaped value from this interaction. After the incident, the flat-stricken traveler made it a point to bring his family to the drive-in and tell his friends about the thoughtful drive-in owner. Both parties saw great value in this relationship knowing each benefited from this opportunity. It can be easy to stumble at times when we forget to meet partners where they stand.

Through such partnerships, the people of Tualatin Watershed are transforming the landscape, averaging more than 10 river miles of restoration annually (195 km in the past 12 years) across more than 25,000 acres. Here are some examples of Tree for All partnerships and how they are working together to further their individual goals while enhancing the benefits that natural resources provide to the community:

Metro: Metro is a regional government and planning agency in the Portland metropolitan area. Metro’s mission to connect high quality stream corridor and wetland habitats across the Tualatin River Watershed has resulted in the protection of almost 5,000 acres of natural areas. Its collaboration with Clean Water Services and other partners on more than a dozen natural areas including Wapato View, Maroon Ponds, and Gales Creek Forest Grove Natural Areas has been instrumental in achieving Tree for All goals. These projects leverage multiple funding sources and create a bigger impact than each organization could complete on its own. By allowing access and combined planning efforts, Metro helps Tree for All achieve a core goal of improving water quality, while enabling Metro to complete enhancement across entire properties where other priorities would have meant leaving them incomplete.

Friends of Trees: Friends of Trees is a nonprofit dedicated to empowering communities to improve the natural world by planting trees. By gathering an army of volunteers every weekend during planting season, Friends of Trees plays a pivotal role in the success of Tree for All. In 2015 alone, Friends of Trees mustered more than 17,000 volunteer hours with a value of $375,000. A decade of partnership translates into millions of dollars leveraged, and thousands of urban Washington County residents connected to water resources.

Tualatin Hills Parks and Recreation District: Tualatin Hills Park and Recreation District (THPRD) is a pivotal partner with more than 1,300 acres of natural areas in Beaverton and adjacent areas. One example is a 35-acre complex on Bronson Creek, owned by THPRD since the early 1990s. The complex improves habitat diversity and water quality in the area while complementing and connecting with nearby restoration projects. By forging this partnership and harnessing multiple interests, the benefits are tangible and growing, all at lower cost than if we each did it alone. Through this partnership, THPRD is making a big contribution to sustaining and enhancing the Tualatin Watershed where residents may live and work in harmony with the environment.

Tualatin Soil and Water Conservation District: Twelve years ago, we saw the first farmer sign up for a new riparian restoration program developed jointly by the local farming community, foresters, environmental groups, and Clean Water Services. By year three, this program caught its stride, leveraging millions of additional Federal To learn more about our partnership with farmers in the Tualatin River Watershed, check out this video about our agriculture partners.

Speaking a common language: using a voice that engages and inspires

Speaking a common language: using a voice that engages and inspires

What’s happening in Washington County is not an accident. We’ve got an incredible effort of all different organizations working together towards one thing, and that is to work with Mother Nature. But we’re all doing that with the understanding that those benefits to each and everyone of us are far, far greater—and it’s not just to us. It’s to the future generations.

– Carolyn McCormick, President and CEO, Washington County Visitors Association

The slap of a beaver’s tail on the surface of the pond sends ducks scurrying, the turtle diving and the songbirds chirping. A red tailed hawk decides to stop and say hello. Isn’t it fascinating how that one voice/tail engaged and inspired such a diverse audience?

How many times do we humans shoot ourselves in the foot when we forget to communicate with a voice that engages and inspires? When I think about my conversations with school children, farmers, and government representatives, it can be challenge to communicate the importance of watershed health using a single message that resonates with all of these groups. It requires accounting for their concerns, speaking to the common values we all share, and conveying the benefits we all experience when we invest in our natural resources. The truth is, we all need clean air, water and healthy soil to be resilient and happy. There are many ways of telling the story about the interconnection between humans and our environment. Tree for All has found great success in telling that story through the many different voices of our partners while speaking a common language through engaging stories and inspiring conversations. This voice becomes very important as partners from diverse backgrounds come to the table to share resources and their experiences across broad landscapes.

Click these links to hear stories from Tree for All’s community, ecology, and economic partners.

As we witness the many stressors associated with interesting weather events and the human desire to grow and prosper, Tree for All partners have clearly demonstrated that it is possible work locally and create the actions needed for watershed resiliency. The next essay in this series will elaborate on how Tree for All catalyzes this community impact through business innovation and co-investment, targeting efforts that provide the best return on investment, and planning for the interests of future generations.

Bruce Roll

Portland

Leave a Reply