STEW-MAP is a tool that helps us understand and visualize how groups steward their local environment, and how their work is part of a larger network of civic engagement.

Worldwide, cities are grappling with aging infrastructure, shifting populations, and changing weather patterns, necessitating the use and expansion of green space in equitable and creative ways. Many are embracing a transition from the sanitary city—comprised of siloed functions and grey infrastructure—to the sustainable city—comprised of regenerative and distributed systems that require ongoing coordination. At the same time, municipal budget constraints create an urgent need for leveraging civic capacity. Even under the best-case scenario, cities invest in their natural resources and green infrastructure primarily through the commitment of capital funds, leading to insufficient support for long-term maintenance of these installations. City agencies do not have the funding or humanpower to maintain these sites and systems alone, and rely on a growing network of civic organizations and volunteers.

If you are a gardener, a park champion, a food justice activist, a kayak club member, an educator, a researcher, or a community organizer—we need your help in putting your group on the map! The 2017 NYC Region STEW-MAP survey is now open! Check your inbox and respond to the survey to make sure your hard work is recognized. If you have not received a survey but are a part of a stewardship group you would like to see on the map, email [email protected]. For more information on STEW-MAP, visit nrs.fs.fed.us/stewmap or email [email protected].

The urban landscape is a co-creation of many, and if we want to improve the quality, accessibility, and viability of our natural resources then it is important to understand not only the resource as a social ecological system, but those who care for it as part of that system. STEW-MAP (the Stewardship Mapping and Assessment Project) began in New York City in 2007 as a way of visualizing the civic groups that provide capacity and take care of the local environment. It is a way to understand the social extent of caring for a place. In urban environments where there are many layers of change as well as overlapping bureaucratic boundaries and property jurisdictions, civic stewardship groups can appear more transboundary as their work and purpose often cross over space, time, and scale.

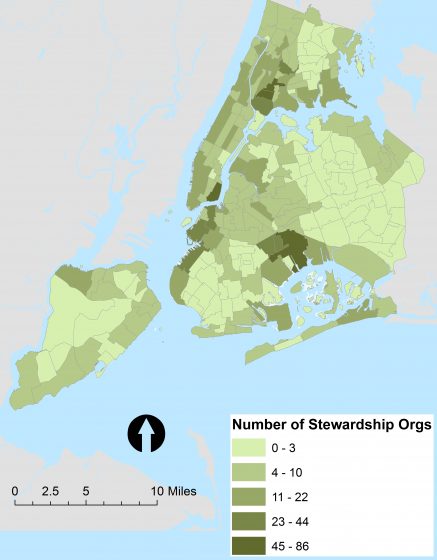

Visualizing and mapping these groups helps point out gaps and overlaps in civic capacity across a city’s neighborhoods. Prior STEW-MAP research found that stewardship groups focused on different issues may be working in the same neighborhood, yet unaware of each other. Also, groups may be working on similar issues, but in different places and without coordination. STEW-MAP aims to connect groups and sites across the entire city’s social-ecological system.

At the NYC Urban Field Station, we define stewardship groups as two or more people working to conserve, manage, monitor, transform, educate on and/or advocate for the local environment—from a group of friends or block association planting flowers in tree pits, to large environmental education NGOs, to grassroots environmental justice campaign. STEW-MAP collects data through a survey, which asks questions about:

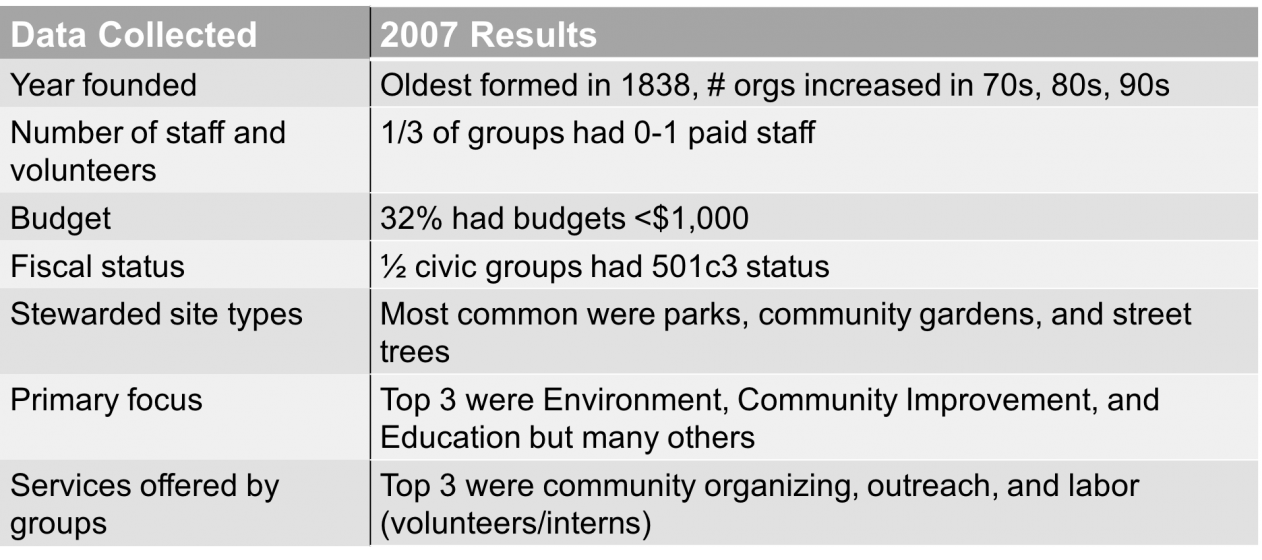

1. Basic Characteristics: The STEW-MAP survey measures a group’s capacity, longevity, structure, and theory of change. Questions address the motivation and the mission of groups, as well as the metrics used to track progress. This information is essential to knowing not only the type of stewardship group but how it is functioning as an organization.

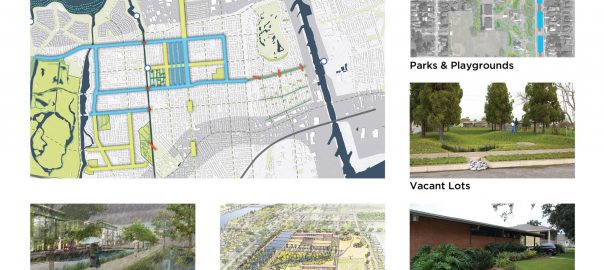

2. Stewardship Turfs: The STEW-MAP survey also maps the physical spaces that stewards care for such as the waterfront, a block or a park and the spaces where systems like waste or air quality touch down in place. Unlike the jurisdictions that govern private property, political districts, and formalized public space, civic stewards are not held to such boundaries. Instead, they create, determine and shape their own turf based upon where they do their work. Stewards can self-define their turf in the STEW-MAP survey, whether they work on a specific lot or an entire borough or waterway. Stewardship is not ownership, it is defined by caring for a place.

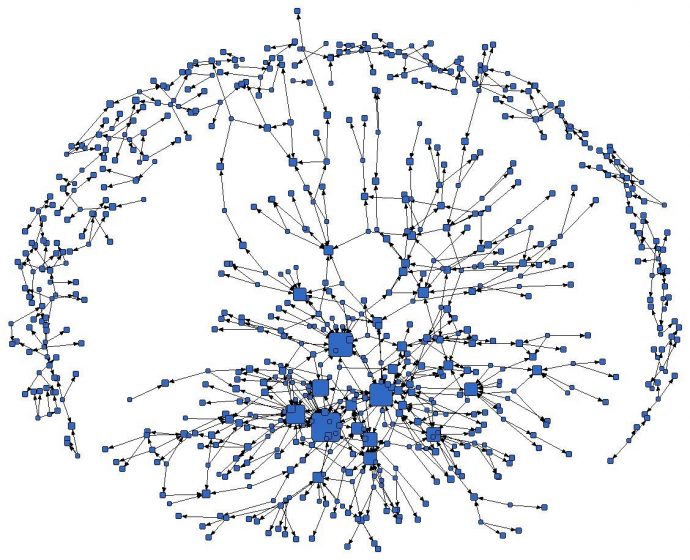

3. Networks and Nodes: Finally, the STEW-MAP survey captures the connections with other civic groups, businesses, and governmental agencies. These include public agencies and NGOs that stewardship groups go to for collaboration and support. Many of these social networks channel resources like materials, labor, and funding. These networks transmit knowledge, ideas, and data, helping to to shape new forms of cooperation and even governance. STEW-MAP allows us to visualize the key nodes or brokers in this network.

The data collected from the 2007 STEW-MAP survey in New York City were analyzed and made into a public database and interactive map designed to help stewards better understand how they fit into their city. Data from the 2007 survey can be found here. STEW-MAP findings from 2007 showed that there are groups of all sizes, shapes, budgets, and structures across the city. However, they all share the way they care about their local environment—which is evident through the strong place attachment, social cohesion, community identity and co-creation of knowledge across a diversity of different site types. Research also found that stewardship groups focused on different issues may be working in the same neighborhood, yet unaware of each other. Also, groups may be working on similar issues, but in different places and without coordination.

Through many years of research, we have learned that people care for that which has meaning in their lives; as Steven Jay Gould famously said, “…we will not fight to save what we do not love.” STEW-MAP helps to understand and visualize how groups are making meaning of their local, everyday environment. In doing so, we find that people can be positive agents of change in our community, and that these acts are more than localized actions but part of a much larger network of stewardship and action. STEW-MAP data adds to our understanding of civic stewardship and can be used at varying scales to improve and grow the network of stewards. It helps visualize universal human behaviors of how we move from individual action to a group action in an effort to care for ourselves, each other, and our environment. It can also help to see these actions within the scale of an entire city or region, noting the places where people have come to invest time, money, labor, and ideas to strengthen and leverage the work through partnership and sustained collaboration with others. Our long-term vision is that stewards of all sectors –civic, public, private—and in all places will see themselves and their efforts as part of a co-creative effort to strengthen our natural resources and our communities.

Since 2007, STEW-MAP has expanded to cities internationally. STEW-MAP projects are currently underway in Baltimore; Philadelphia; Seattle; Chicago; Portland, Maine region; Los Angeles; North Kona and South Kohala regions in Hawaii; Paris, France; San Juan, Puerto Rico; Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic; and Valledupar, Colombia. A 2016 Forest Service General Technical Report describes the steps for undertaking STEW-MAP in new cities.

In 2017, we are working to update and expand STEW-MAP in New York through a regional survey of stewardship groups. STEW-MAP 2017 builds upon past research, providing the first update in 10 years on previously participating groups. In addition to capturing change over time, the 2017 survey data will reveal the ways in which the larger stewardship landscape has evolved in the New York Region, including how the changing climate, political administration shifts, social movements, and environmental disasters have influenced the goals and methods of stewardship groups.

Laura Landau, Lindsay Campbell, Erika Svendsen

New York

about the writer

Lindsay Campbell

Lindsay K. Campbell is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service. Her current research explores the dynamics of urban politics, stewardship, and sustainability policymaking.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

Leave a Reply