Engagement is the first step toward active acknowledgment, inclusion, and stewardship of the environment. Nature Atlas provides a rich tapestry of options for engaging with urban nature.

Edward O. Wilson popularized the concept Biophilia more than 30 years ago, in 1984, describing it as “the urge to affiliate with other life forms”. In short, Biophilia is a hypothesis that suggests the innate affinity of humans towards nature. We agree that humans possess the tendency to seek connections with nature—whether as a place for escape from the busy and chaotic city life, or as scientists curious to learn about other life forms, or designers seeking inspiration from natural habitats/environments, or as artists fascinated by colors, forms, shapes, and habits—we all share a love for living systems. It is this tacit, inherent connection between humans and nature that we explore in this essay and wish to make explicit through a research project based on Ruchika Lodha’s master’s thesis, called Nature Atlas, which excavates hidden layers of urban environments by mapping relationships between humans and nature. With this project, we hope to broaden the spectrum of human engagement with nature, to deepen awareness and knowledge, invoke curiosity to observe, interact, and engage, all as a way to help create a culture of stewardship toward our urban (and non-urban) environments.The purpose of Nature Atlas is to invoke diverse ways of perceiving, understanding, and engaging nature by actively and consciously interacting with our environments through various practices across disciplines, inclinations, expertise, and capacities.

In the Anthropocene, people may be aware of and concerned about the environment, but there are many factors that deter them from being actively engaged with the nature around them. There are time constraints, lack of knowledge or expertise, fear of nature, and many other possible reasons. Engagement is the first step toward active acknowledgment, inclusion, and ultimately stewardship for environments (accreting toward nature at large). Personal associations and attachments that people build with environments provide stronger and more permanent motivations for engagement and stewardship (Nassauer 2011). The aim of Nature Atlas is to involve people with various interests and expertise to create a collective consciousness toward our environments.

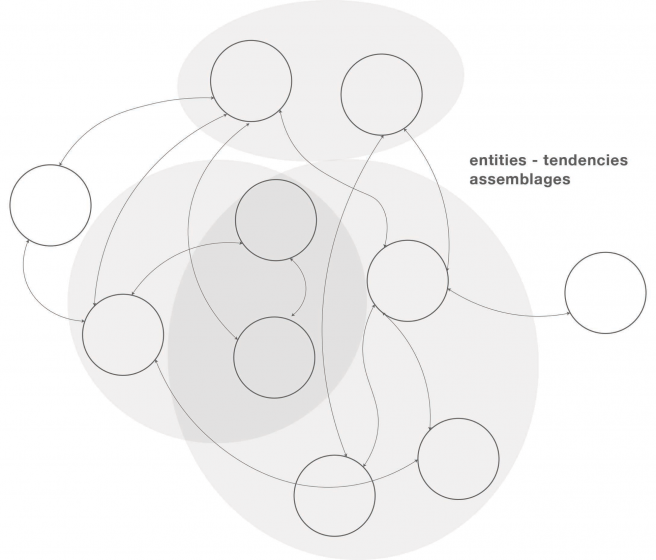

Developed over 2016 and 2017, Nature Atlas employs alternative mapping techniques that go beyond top-down, two-dimensional spatial visualization to employ mapping as a reflexive, sensorial, and immersive methodology to excavate the unseen, tacit, or disregarded layers of nature within a case study in New York City, the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. This kind of mapping provides a wide range of inspirations and real-life projects to evoke readers to engage with the environment in their own ways without suggesting one universal or “best” strategy. The Atlas, thus, is a compendium of interpretative and speculative maps, diagrams, illustrations, and stories visualizing quantitative, qualitative, archival, scientific, empirical, and anecdotal research.

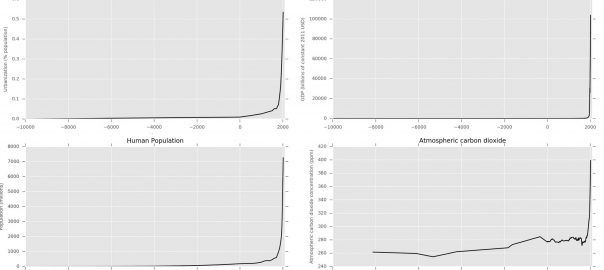

We envision the Nature Atlas as a step toward the creation of a broader collective of knowledge that yields diverse ways to actively and consciously recognize, interact with and engage nature through sensorial experiences, reflection, and speculation to understand how we (may) intervene with/in the Anthropocene to shift the present toward a more desirable future, Good Anthropocene (Bennett et al. 2016, McPhearson et al. 2017). Below we iteratively map layers of history of the Gowanus Canal, Brooklyn as a basis for exploring the current landscape of contemporary imaginaries and engagement of this changing nature in the city. This historical lens provides an opportunity to compare shifts in human-nature relationships through time.

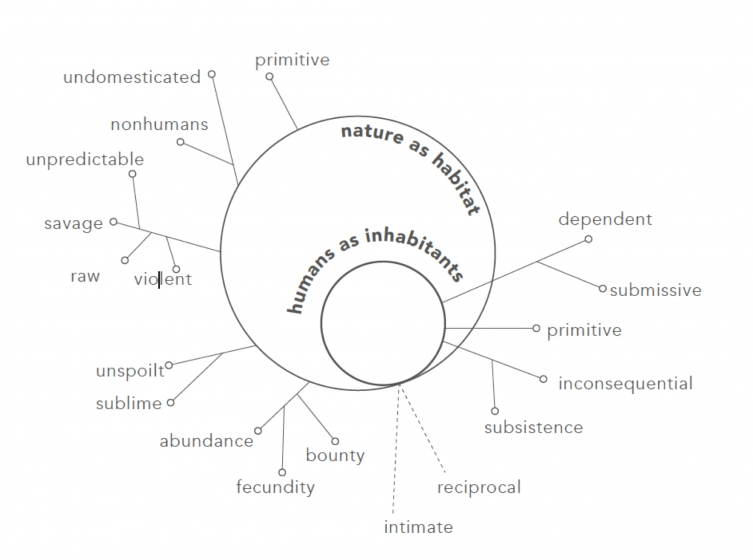

“Primitive nature”

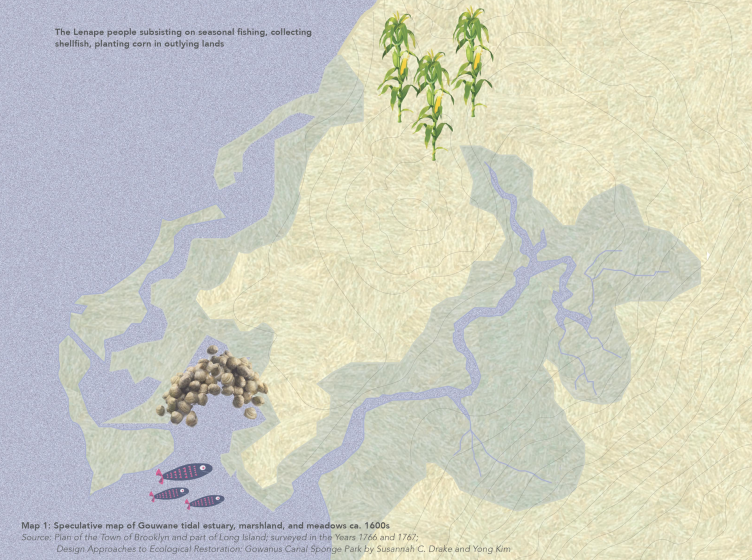

About four centuries ago, Gowanus was a saltwater marshland and meadows called Gouwane after the chief of the Lenni-Lanape group (Alexiou 2015), who were its earliest inhabitants.

The natives lived well off the tidal inlet of the marshland—a creek, then—through subsistence farming (of corn in the outlying lands), seasonal fishing, and collecting shellfish. These early inhabitants shared resources and lived intimately with nature, ebbing and flowing with its bounty.

European Encounter

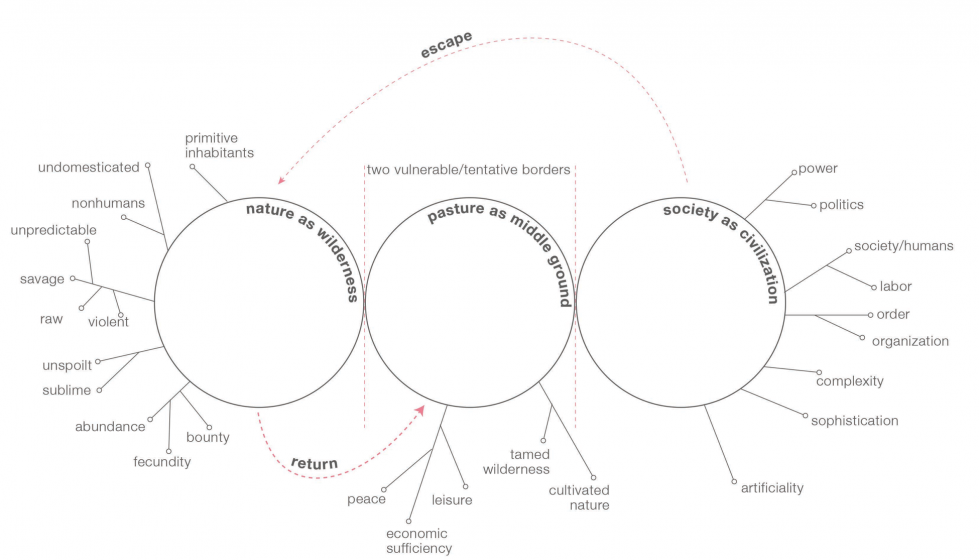

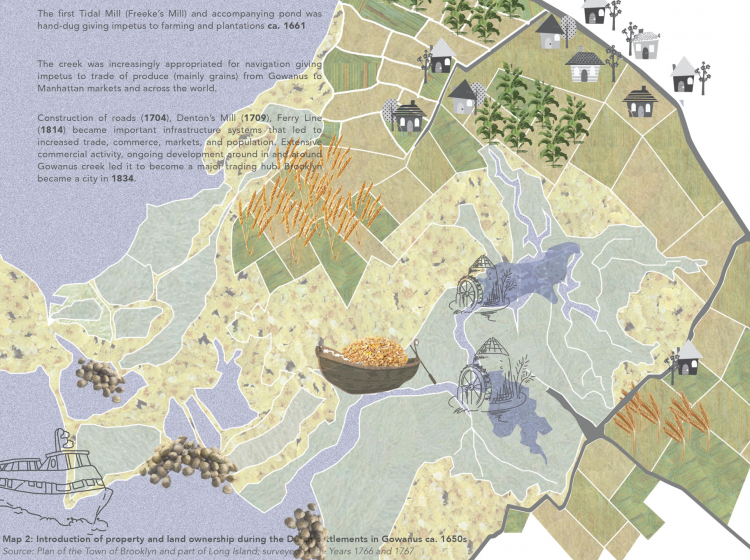

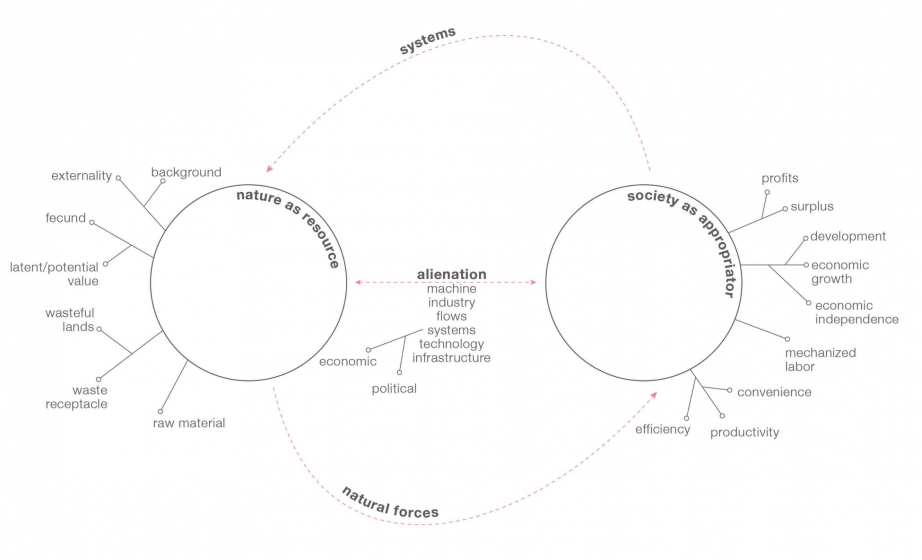

Europeans first arrived in Gouwane around the 1630s and settled in the area, intrigued by its plentiful and pristine nature, which was unlike the ordered and complex European cities (Alexiou 2015)[1]. The Europeans introduced new concepts of land ownership, property, and regulation. They appropriated and tamed the topography by delineating land, water, fields, settlements, constructing mills and roads for farming, fishing, trade, commerce, and navigation. The creek became a means to cultivate and transport produce from Gowanus to Manhattan markets. These delineations between land and water, labor and leisure, nature and society that were nonexistent or mutable before the arrival of the Europeans became clearly defined boundaries with distinct meanings and functions. Nature was therefore “tamed” and appropriated to create an ideal middle ground or pastoral ideal between wild, primitive nature of Gowanus and highly organized European societies to fulfill needs beyond subsistence, arguably producing a dichotomous relationship between nature and society.

Commercial nature

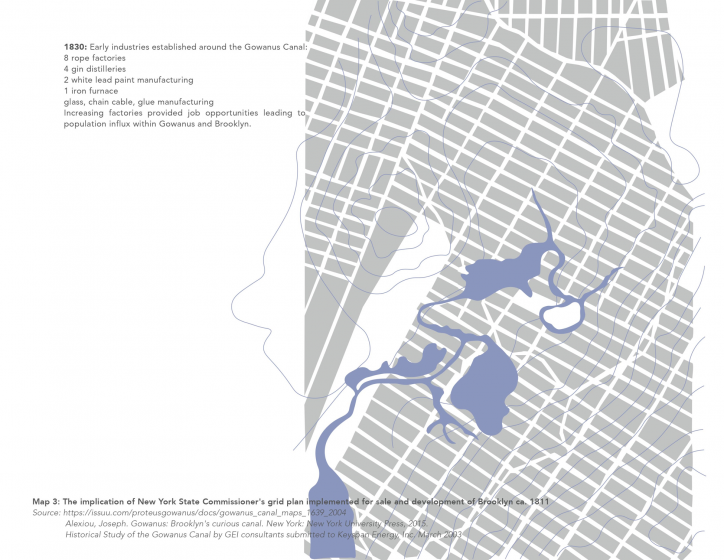

The nineteenth century saw the establishment of many early industries along the creek. Political and economic structures increasingly influenced and subsumed the topography of Gowanus. Infrastructural systems including the construction of the canal were seen as engineering marvels that eased the processes of manufacturing, trade, and commerce providing economic gains and convenience for sewage discharge. The canal became a raw material for exploitation and a waste receptacle for industries and society rather than an environment to inhabit and appropriate based on needs for subsistence (as in the 1600s). Mechanized labor, driving economic and political systems, and technological advancements, dictated its use and form changing the perception, function, and interaction with inhabitants intensifying the separation between society and nature.

Post-industrial detritus

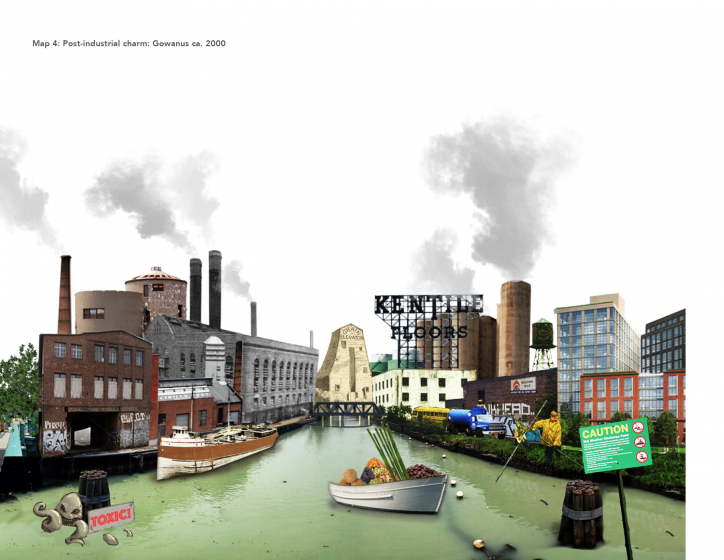

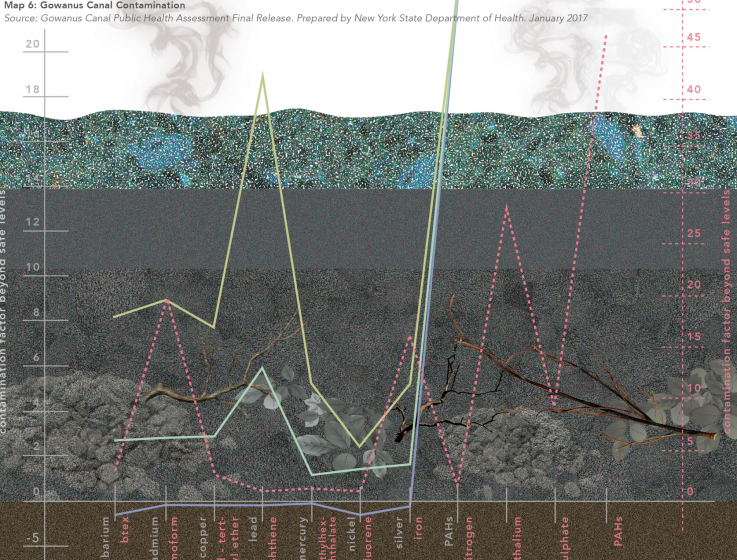

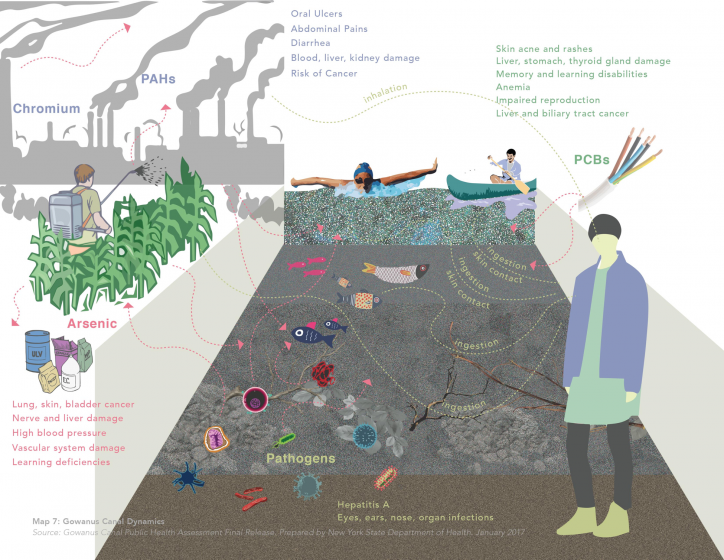

Since the stock market crash during the Great Depression in 1929, development and construction in Gowanus were almost completely at a stand-still due to lack of investments. The century and a half long industrial history that led to its glory, progress, and development also resulted in extreme contamination and toxicity in the canal. Map 4 hyperbolizes the post-industrial landscape of Gowanus Canal. It is a juxtaposition of industry, trade, commerce, prosperity, stagnation, toxicity, grime, romanticism, and charm. This perception of Gowanus Canal exposes contesting and overlapping epistemologies of nature. In the early twenty-first century, after residents and government officials raised concerns and voices, the site was studied and sampled producing reports of contamination levels and its effects on public and environmental health. This was representative of the acknowledgment of the interconnectedness between nature and society. After two years of deliberation, the government eventually designated Gowanus Canal a Superfund site, placing it on the National Priority List 2010. The site is now managed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) and undergoing remediation and cleanup.

Contemporary nature

The current remediation plan envisions Gowanus Canal as an amenity to human society, an accessible piece of nature with flourishing habitats for plant, animal, bird, and aquatic species. Even though there are efforts to clean the canal and employ design strategies to acknowledge, address, include, and improve habitats for other species that cohabit the environment with humans, the vision co-opts the idea of a pastoral “garden” that manifests the reconciliation between deteriorating wild nature and extremely chaotic society through technology. Although there is awareness of the interconnectedness between societies and nature, nature is still perceived as an externality that supports and situates society. The knowledge produced through literature and scientific research that promote ecological thinking are often inaccessible or abstruse to laypeople.

Actionable engagement

In this section of the Atlas, we list projects and practices that critically engage with nature through various disciplines and skill-sets including science, research, design, photography, art, and pedagogy as a pathway for the multi-scalar approaches for initial and ongoing environmental engagement. This collection hopes to provide inspiration and invoke readers from various backgrounds, with diverse inclinations and capacities to engage with nature by actively observing, acknowledging, interacting and engaging with their environments. The Atlas may also become a live archive connecting people and building networks among similarly-inclined practitioners and aspirers while bridging the gap between the literature on nature and empirical experiences through multidisciplinary practices.

Interpretive reporting is a method to translate long, tedious, and abstruse scientific reports into accessible and legible (visual) information to a population that is not academic or scientifically-inclined.

Relational reporting allows us to map the relations between things, facts, implications, causes to understand the connections within a situation or context under consideration.

The Verge Workshop, “designing for inclusion” aimed to engage students and scholars from various backgrounds in an open-ended collaborative discussion around invisible actors, systems, and structures within the framework of extractive economies and environments.

Ellie Irons is an interdisciplinary artist with a background in environmental science whose practice explores human-nature relationships through interactive, exploratory, recreational, and fieldwork-based methods. The Invasive Pigments project focuses on what she calls “spontaneous urban plants” or invasive weed species that rapidly grow within densely populated and developed urban landscapes in order to make pigments to produce paintings, diagrams, or field guides. Whereas, the Next Epoch Seed Library is an archive and seed exchange program that promotes awareness of and engagement with urban plants.

Conclusion

Nature is a complex realm with many meanings and manifestations and for many can be daunting to engage with. Ambiguous genealogies discussed as part of the history of the Gowanus debunk the need for a universal theory to understand or know nature. Our interest here lies in exploring the multiplicities of epistemologies of nature and the shifting relationships of humans within nature to elicit new ways to engage with nature within situated urban environments. This collection of “maps” is both a research method and a presentation technique that expands the scope of and translates abstract and esoteric literature to understand and engage nature within empirical context in two ways: one, by re-telling the story of Gowanus with the focus on human-nature relationships, and two, by addressing the diversity of epistemologies of nature through an assembly of praxis projects in order to create a collective knowledge of and engagement with nature.

As a research method, the Atlas suggests observing and interacting with the environment in a conscious, analytical, and sensorial manner by revealing covert layers. In the case of the Gowanus Canal, the alternative mapping techniques incite the acknowledgment of smells, weeds, “inanimate matter”, and micro-ecologies within the water and soil of the canal. As a presentation technique, the Atlas distills complex information like the transformative history of the landscape of Gowanus, and scientific reports on contamination and health impacts into easily comprehensible visuals through story-telling techniques. In both capacities, the Nature Atlas provides for a pedagogical tool that helps conscious, and more involved interaction and understanding of our environments. Bringing this into local neighborhoods, classrooms, community organizations, and backyard barbecues is the next step to link multiple ways of understanding and to connect to the everyday nature in our communities and streets.

Ruchika Lodha and Timon McPhearson

New York

This research, including mapping, interviews, and workshops, was conceived and conducted as part of Ruchika Lodha’s unpublished graduate thesis (2017) for MA in Theories of Urban Practice at Parsons School of Design.

[1] Ibid.

Cited Literature:

Bennett, E.M., M. Solan, R. Biggs, T. McPhearson, A. Norstrom, P. Olsson, L. Pereira, G.D. Peterson, C. Raudsepp-Hearne, F. Biermann, S. R. Carpenter, E. Ellis, T. Hichert, V. Galaz, M. Lahsen, M. Milkoreit, B. Martin-Lopez, K. A. Nicholas, R. Preiser, G. Vince, J. Vervoort, J. Xu. 2016. “Bright Spots: Seeds of a Good Anthropocene.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(8): 441–448, doi:10.1002/fee.1309

McPhearson, T., D. Iwaniec, and X. Bai. 2017. “Positives visions for guiding transformations toward desirable urban futures.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability (Special Issue), 22:33–40 DOI: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.004

Nassauer, Joan Iverson. “Care and stewardship: From home to planet.” Landscape and Urban Planning 100, no. 4 (2011): 321-23. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.02.022.

Alexiou, Joseph. “Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal.” New York: New York University Press, 2015.

about the writer

Timon McPhearson

Dr. Timon McPhearson works with designers, planners, and local government to foster sustainable, resilient and just cities. He is Associate Professor of Urban Ecology and Director of the Urban Systems Lab at The New School and Research Fellow at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies and Stockholm Resilience Centre.

Leave a Reply