I spent a year documenting the on-the-ground reality of local farmers and villagers, in an attempt to provide an alternative to development maps offered by centralized planners.

#watchingthericegrow is a hashtag I created on Instagram on 4 August 2016, tagging a photo I took from a bicycle survey along a winding rural road on the outskirts of Chiang Mai, Thailand. The initial framing marked a memorable composition at the center of a territorial survey that would spiral out from this center. The posting announced my commitment to an on-line audience to take a picture on that same spot for the entire growing season. My goal, to not only watch but document the rice grow for the following three months was extended to a full calendar year, as my last post was on 4 August 2017. In the year, I documented the growing and harvesting cycles of two crops of rice. I supplemented the Instagram posting with various forms of videography: drone, handheld from a moving bicycle, and contemplative close-up still shots of the community irrigation weirs that dot the landscape.

As an architect and urban designer from a generation that made the transition from analogue to digital media, I have been interested in how forms of new media create new publics and audiences for mapping as well as new forms of social agency in urban design decision making. #watchingthericegrow will provide material, for on-line and in gallery exhibitions, which defines the villagers and farmers of Chiang Mai as the land artists and the owners of the map of the Lanna Territory, and important agents in deciding its future. Local narratives and visions provide alternatives to standard development strategies hatched in Bangkok. It is imperative that artists, designers, and social activists endeavor to assist in communicating local knowledge.

Marking a start

I was looking for a composition I would remember. I frame a lush tree in the middle of the straight rows of seedlings in my view finder. A narrow irrigation canal cuts an angled path across two paddies, a giant check mark formed by two raised berms channeling water to the fields. There is a slight grade change between the higher paddy on the right, and the lower one on the left, with a cut in the berm, allowing the adjustment of the water level between the two paddies. The edge of the rural road is in the foreground, and a black and white painted sign post marks my vantage point. My weekly posting documented the growing and harvesting cycles of two crops of rice between August 4, 2016, to August 4, 2017.

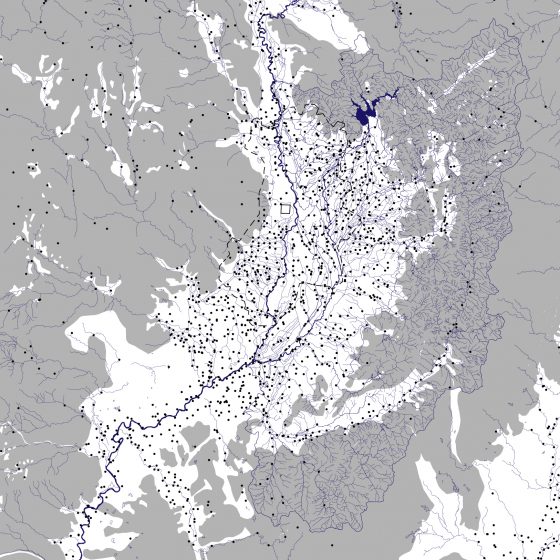

This rice field sits between the village and Buddhist temple of Tha Thum, seven kilometers east of the center of the historic city of Chiang Mai, Thailand. The field, village, and temple are an example of the hundreds that dot the Chiang Mai/Lamphun Valley in Northern Thailand. The region, historically called Lanna, which means “a million rice fields”, is one of the most fertile in Thailand, and a complex gravity-fed, wet rice growing irrigation system developed over hundreds of years. The system was both royally supervised and locally managed through a community-based, water sharing network called muang fai, which refers to the weirs and canals that divert river water to fill the thousands of rice paddies that comprise most of the historic valley.

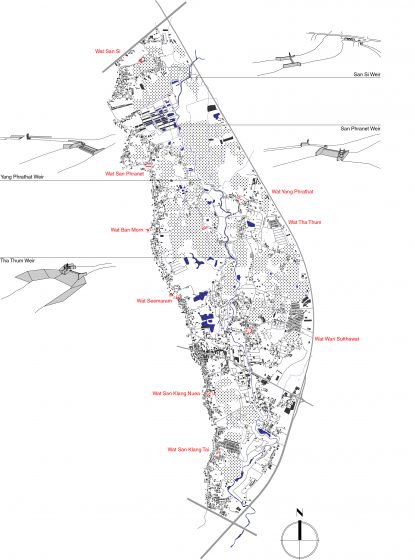

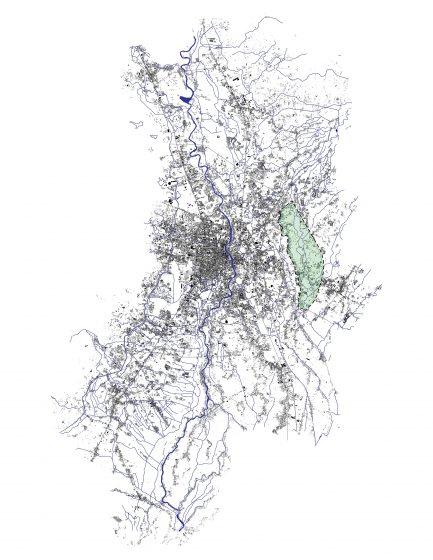

I intended to survey this system outward from this marked point by bicycle and foot, limiting the area geographically, but not focusing on a single village. The area I studied was bounded by the new national highways recently constructed across the valley—the outer ring road to the east, Doi Suteph Road to the north, and new San Kamphaeng Road to the south. The western border was the busy rural San Phranet Road. The rural open matrix of the muang fai system is transforming to a fragmentary urban/rural mix as land is fenced and filled for new houses.

New developments along the radiating highways and ring roads generate commercial strips and gated residential communities, but the within this superblock there are many dead-ends and overgrown vacant areas that remain from a previous period of land development and subdivision. In addition to the bounding roadways defining the site survey, at its heart is where the Mae Kuang River passes in and out of the urbanizing area encircled by the outer ring road. The area is approximately 12.6 km2 considering the boundaries of the highways and the village road. The east-west distance is approximately 2.8 km between the village road and the ring highway. The north-south distance is approximately 8.2 km between the two intersections of the radiating highways and ring road.

My bicycle survey comprised the circuitous route between these fragments, never crossing the obstacles of the highways. The area is like the one that Terence McGee described as Desakota, named after the rural and urban mix he identified in Indonesia. A major trigger for this kind of dispersed urbanization is the arrival of motorcycles to relatively dense rice growing landscapes. My two-wheeled survey was intended to help me understand the spatial imagination of the locals navigating between farm, village, and city, rather the mindset of the city’s planners and traffic engineers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOMQ-6ooT2c&feature=youtu.be

Video: The field survey was conducted by bicycle in order to acquire the two wheeler understanding of the farmers and villages.

The Mae Kuang River is a major tributary to the Mae Ping, and the two rivers occupy seismic fault lines, forming the valley and the alluvial plain that allowed the Kingdom of Lanna to flourish from its founding in 1296. Chiang Mai means “new city”, and it is located on a slightly higher elevation west of the Mae Ping, with its western gate leading to the royal gardens at the foothills of Mount Doi Suteph. The main rice fields were in the “belly” of the valley, southeast of the city, around the older city of Lamphun, located on the Mae Kuang River. The muang fai system begins with the royal project of diverting the rainy season excess from the Mae Ping through a long canal parallel to the river. The weir construction was an enormous effort, necessitating the marshaling of thousands of laborers to annually reconstruct the weir (fai) and dredge the canal (muang). Once this conscribed labor was complete, villagers were free to manage and maintain smaller muang fai, under the local supervision of a weir headman.

The Mae Kuang watershed is drier than this flood plain at the bottom of the valley, and a modern dam and irrigation system built by the national Royal Irrigation Department (RID) was overlain on top of the traditional muang fai irrigation system. However, the majority of the land is still farmed using an upgrade to the traditional wood, bamboo, rock, and silt fai. Called the “people’s irrigation program”, RID converted many of the old fai into concrete foundations that farmers could adjust to continue their practice of diverting river water to muang.

Same-same but different

Eventually, I discovered four fai within this stretch of the Mae Kuang. The one at Tha Thum and San Si villages were quite easy to find as they were located near bridges over the Mae Kuang on two of the narrows rural roads that I bicycled over to survey the area. San Si includes of two shallow fai and a major diversion muang that feeds an enormous rice field located below an area of more recent industrial farming activity. Tha Thum is the highest fai I found, a spectacular four-meter high falls located just below a royally initiated fish hatchery and water plant harvest area. At this time, I conducted a drone survey to locate additional fai in the area of the river not accessible by bicycle.

Video: Drone from Tha Thum weir. Pilot Santipab Sonboom, October 2016.

With the onset of the dry season, at the start of the new year, I was able to bike along the river embankments south from the weir at San Si and soon discovered a third fai, directing a muang westward towards the village and temple of San Phranet. While the muang from San Si fed the enormous field adjacent to this fai, this muang disappeared into the forest on the other side of the river. I chose to continue surveying the field fed by the San Si muang fai, which continued as a lush farm to the south before the muang drained back to the river. The gravity fed loop of the irrigation system was now apparent in this closed circuit, where the river water fell approximately one meter at the San Si fai and another two meters at the San Phranet fai. The muang gently sloped, and the scores of paddies slightly stepped over the course of this drop.

I discovered the fourth fai by biking through the rice fields beyond the temple at Tha Thum. The temple, like my original marker tree, is surrounded by lush, active paddy. I was able to find the water source of the fields and trace a minor branch to a major muang, biking along its embankment, through the small settlements of a chicken farmer and woodworker before I found a spectacular fai that was feeding the Tha Thum fields. This bucolic spot was only accessible by foot, but the sound of the falls led me on, even when the pathway gave way. This fai was a short distance upriver from the village of Yang Phrathat, where a riverfront pavilion created a covered meeting space for the area’s villagers.

I followed the last muang from Tha Thum fai through an urbanized area with scattered fields. East of the Mae Kuang, where the ring road bows away from the river, scattered fields fed by an unknown fai surround Wari Sutthawat village and temple. Finally, south of the old San Kamphaeng Road, a branch of the fai fed a few rice paddies, but most of the field was not fed by the system. However, I met a farmer, pumping water up from the Mae Kuang to mechanically irrigate an organic asparagus field he was cultivating, for export to Europe. This area along the river is dotted with earlier developments, many of them incomplete, vacant and overgrown. The 700-year anniversary celebrations of the founding of Chiang Mai were followed in 1997 by a severe economic crisis, and countless real estate developments were abandoned with bankruptcy. If the upper half of the site is dominated by the two large rice fields, to the east and west of the Mae Kuang as it winds around Tha Thum temple, the bottom half is dominated by a secondary forest covering these abandoned landfilled zones.

Scaling up

The four villages and four muang fai discussed here are both in a particular position with the urban/rural interface of Chiang Mai, but also can be generalized to understand the challenges the entire valley faces as urbanization pressures rural life. The Chiang Mai Comprehensive Plan designates the land in between the radiating highways along the ring road as an agricultural preservation zone. However, the new ring has triggered much new development. Within my site boundaries, the Mae Kuang is marked as the boundary between agricultural preservation and low-density urban development, even though as the survey shows, farmland is fed by a muang fai system on either side of the river. A specific solution for this important site where the Kuang River passes through urban land is to preserve these large rice fields and two-wheel paths as important open spaces and trail ways within the city periphery. This proposal is also a model for the rest of the territory as urban development spreads from the newly widened radiating highways.

During my survey year, there were many community meetings as another road is planned to cross the site below Tha Thum. In these meetings, villagers are presented with schematic planning maps and asked to offer input. They are not the “owners” of these planning maps, yet they are subject to the planning map’s ordering of their land. My project seeks to understand the farmers and villagers own mental maps of the territory and to use that as a basis for an alternative planning and design process for Chiang Mai. I borrow the term “owners of the map” from anthropologist Claudio Sopranzetti, who’s ethnography of motorcycle taxi drivers in Bangkok revealed their keen tactical knowledge of the city. As Thai scholar Thongchai Winichaikol has written, maps conform on us a “geobody”, usually of belonging to a nation-state. I hoped to embody this two-wheeled understanding of the Lanna territory through this year-long survey.

The farmers and villagers seem ready to fully engage in creating a more comprehensive transformation of the territory. Smartphones and a 4G internet network are widely present in the area. In fact, villages have formed “Line” social media groups to post images and discuss many issues of concern. I wonder if planning agencies located in Bangkok and provincial capitals are ready to hear the villager’s messages and understand their alternative maps of the territory, rather than relying on the simplistic ones created in their offices. I wonder if Terry McGee’s Desakota, created through the accessibility afforded by two-wheeled mobility, will be embellished and maintained by modern social communication and networking technology.

Brian McGrath

New York City

Leave a Reply