The manipulation of our hidden hydrology and the desire to connect back to these lost traces is a commonality we share distinct from culture, geography, and ecology. It is a story reflected in every city, and manifest in every old blue line on every old map.

This was the inspiration for Hidden Hydrology (www.hiddenhydrology.org), my homage to these histories and a way to connect this to my work as a landscape architect and urbanist. The tagline is “Exploring lost rivers, buried creeks & disappeared streams. Connecting historic ecology + the modern metropolis.” A long-time passion for historical ecology, fired by pioneers like landscape architect Anne Whiston Spirn and her work in Philadelphia and Eric Sanderson’s Mannahatta, with its evocative maps of disappeared streams, and inquisitive essays of place by the likes of David James Duncan, led me to more formal research. Starting in late 2016, and through this recent work, I’ve been uncovering and sharing the projects and activities of many urban historians, hydrologists, artists, mapmakers, photographers, and others, including some that have made it to TNOC as well. All of these share a focus on celebrating the lost rivers, buried streams, and disappeared streams in their cities.

Map:

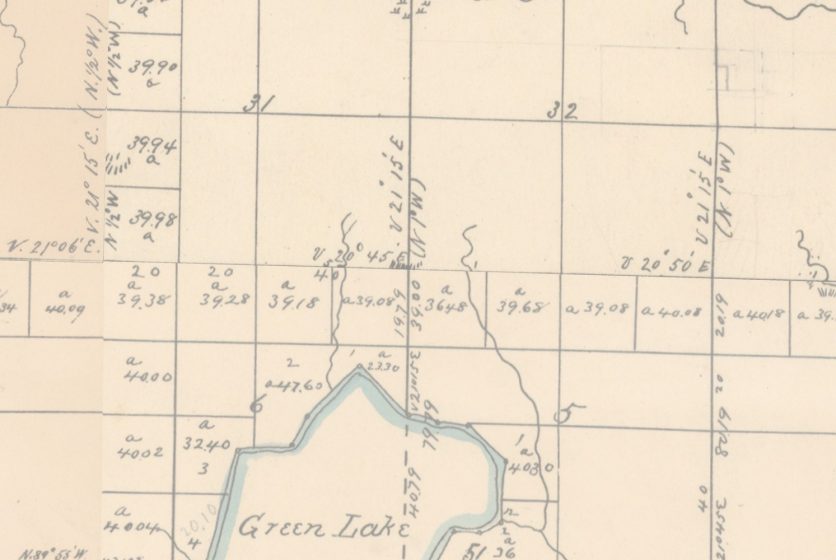

The hidden hydrology of cities manifests itself in unique ways. On a number of walks in Seattle last summer, I followed the routes of urban creeks and discovered that while hidden, the traces left behind reveal layers of meaning. One notable exploration was of an historic waterway known as Licton Springs Creek, in North Seattle. Licton Springs Creek is a short stem flowing north to south, and feeding Green Lake, which is the center point of a significant park in the inner north neighborhood of Seattle. The original General Land Office Cadastral Map from the 1850s revealed the creek.

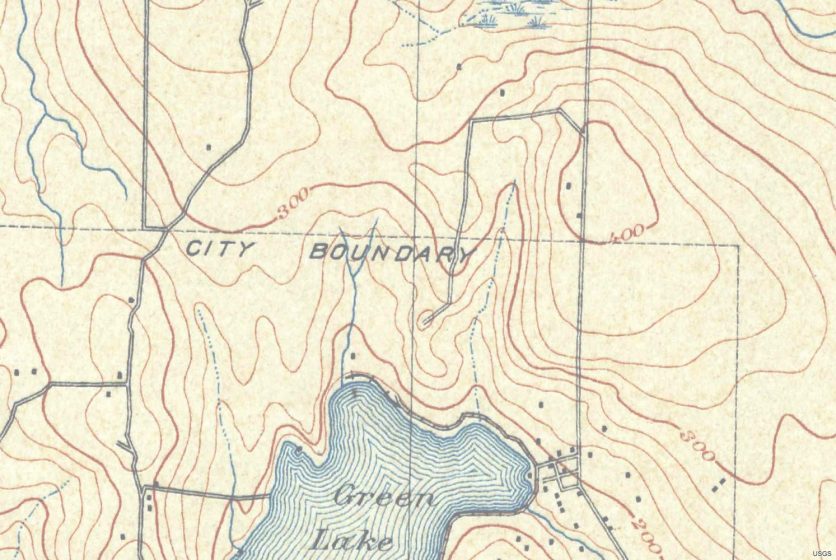

The more detailed 1894 U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) topographic map shows the same forked creek along with some topography. The interesting take home message here is the absence of development, with only a few informal roads and a scattering of houses on the banks of the lake, just a bit over a hundred years ago.

The composite map, digitized into a Geographic Information System (GIS) and married with the database of information and aerial photos, provided the current context for the area including the existing open waterways. This became the blueprint for a route to explore. Although the map shows the creek as a shorter waterway, the current water route implies that the creek started further north, at Licton Springs Park.

Explore:

With maps in hand, the process of exploration is easy. Find a good starting point and try to follow the route as closely as possible heading downhill. For this particular site, there were some springs emerging in the neighborhood, and these all led to a significant portion of the original creek in Licton Spring Park. The map below shows areas of “open channel” that exist within the residential neighborhood.

Walking a few feet off the sidewalk, you begin to hear the rush of water, and as it gets louder and louder, you find the inflow pipes feeding the creek. Three of these pipes drain other upland water bodies, feeding water to the existing daylighted portion of Licton Springs Creek, which weaves through the park, in both channel form and spreading into a larger wetland, with pathways and bridges crisscrossing at points.

In the park itself is the namesake Licton Springs, a serene spring consisting of a simple basin with an outlet, which is striking from the reddish tint of the sediment, caused by red iron oxide. From the Licton Springs Neighborhood page, some history of the spring and its significance to native people:

“Aurora-Licton Springs was once heavily forested, filled with springs, bogs and marshes. The Duwamish Indians called the springs Liq’tid (LEEK-teed) or Licton. Liq’tid means “red-colored” or “painted” in the Puget Sound Salish language, referring to the red iron oxide that still bubbles up in the springs. The springs had spiritual significance to the Native Americans who camped and built sweat lodges nearby, using the reddish mud to make face paint.”

The springs were a constant destination for native peoples as well as early settlers, including habitation in and around the location of the park, which provided recreation for inhabitants (see an interesting write-up on the site at Holy and Healing Wells). David Denny built a cabin on the site in 1870, and other habitation continued in the adjacent area for years. It is still used as a harvesting and recreation destination by the Duwamish. The pressure to develop this area led to the typical cycle, with concerns about the water quality.

Via Wikipedia: “The natural spring fed Green Lake before it was capped and drained to the Metro sewer system after it became contaminated by residential development (1920, 1931).” The typical “modernization” of city infrastructure in the early 1930s, the shift from destination to development and erasure, happened throughout the area.

“Throughout the years, settlers and city dwellers came to the springs to picnic, drink the mineral water and to ease the aching legs of draft animals by soaking them knee deep in the mineral mud. Until 1931, when Seattle diverted the spring’s water to storm drains, Licton Creek fed Green Lake. Eventually most of the springs and bogs in the area were filled to create buildable lands. The natural wetlands were further drained because they were thought to be a health hazard.”

The area of the current park was always a vision, although it took many years to come to fruition. A development in the 1930s proposed a park plan from the Olmsted Brothers on the site, which is captured in a summary from Historylink:

“The Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts, were retained by Calhoun, Denny & Ewing to draw up plans for a park. They proposed an organic layout with a park, rustic drives, paved streets, and home sites. The Olmsted plan, never fully realized, included rustic shelters over the two spring basins, bridges, paths, and clearing the reserve around the springs as well as preservation of the original, rustic Denny cabins. One remnant from the Olmsted plan for Licton Springs that exists today is a portion of the street network, where Woodlawn Avenue curves to connect with N 95th Street.”

The park plan wasn’t implemented, but the land was used for a spa operated by Edward A. Jensen, which “offered thermal baths that included 19 minerals. Jensen also bottled the water and sold it countrywide.” After his death, the land was slated to be developed as a sanitarium but escaped this fate by being purchased as park land by the city. The park was developed officially in the 1970s, and the connection to the streams was maintained. The outfall to the south is a garden entitled “Healing Hands” designed by landscape architect Peggy Gaynor. Gaynor created drama with ripples transitioning to the grand finale—a larger grated outfall creating a cacophony as it exits into the storm system. The area also includes a bridge crossing a rock-lined channel planted with a mix of streamside vegetation.

Beyond the park, my thought was that there would be no remnants left of Licton Springs Creek as the remainder of the route is built-up residential neighborhoods. This is where exploration pays dividends, opening up layers of urban history that, if you wander, stop and look, tell unique ecological stories of our places. In this case, two hidden hydrological features emerged to complete the story of Licton Springs Creek.

The first is a gem known as Pilling’s Pond, which is a discovery that opens up new understandings of place. As you near the site, it seems a little different, surrounded by a chain link fence behind which is a large spring-fed pond, teeming with unique residents—waterfowl. An interpretive sign on the site tells the story, with a short excerpt from the Licton Springs Neighborhood page:

“At around 1933, Chuck Pilling dammed the creek that runs through the property from Licton Springs. This enabled him to provide a habitat that still exists and sustains a broad assortment of waterfowl today. Chuck attracted worldwide attention as the first successful breeder of the hooded merganser, bufflehead and harlequin ducks. Chuck’s hobby has turned into a major community attraction. With people stopping to look at the unusual assortment of water birds, both tame and wild it is a truly unique treasure enjoyed by the entire community.”

You can read the history of this fascinating guy, the connection to Licton Springs, and also check out a video excerpt from the documentary “Chuck Pilling’s Pond: A Seattle Legacy”.

A block south of the pond is what I call the Ashworth Neighborhood Stream, in which the historic Licton Springs Creek (albeit radically altered), is still present, channelized through the front yards of an entire residential block. The small channel slices through the front yards, with various types of bridges spanning the waterway, providing a hint of audible running water from the sidewalks, a rarity in a built up urban area.

Toward the end of the walk, you arrive at Green Lake. The old inflow to the lake is no longer visible, and the location is not the exact stream route of Licton Springs. However, there is an abstracted sequence of water features at the Green Lake Wading Pool that provide a hint of what used to be, including an inlet from the north cascading into a sinuous pool, which overflows under a simple bridge before entering Green Lake. It is a metaphorical connection at best, but one that at least ends the journey in a way somewhat more poetic than a pipe.

You can read a longer exploration of Licton Springs Creek here.

While this is a story about Seattle, it’s merely the story of one creek, which is sometimes visible, but much of which is obscured from our daily lives. It is also a story that is reflected in every city, and manifest in every old blue line on every old map. While pouring over maps, referencing old reports, and digitizing stream corridors into GIS is a nerdy and noble pursuit, and hours of fun, the most compelling advice I have to offer to engage in these places is to get out and walk them. Walking allows us to see our home places in new ways, as evidenced by a wide-ranging literature from amazing authors and explorers alike, such as Robert Macfarlane, Rebecca Solnit, and Lauren Elkin. Walking is a natural act but walking with purpose sometimes is a mystery. In this manner we are not following a trail, nor are we just aimlessly wandering. The act of tracing hidden streams, shorelines, and other waterbodies exists somewhere in between the two. In this regard, it is neither walking for exercise nor walking just for the sake of walking, but a sensory way to engage the body that connects the present and the historical.

For these walks, I have few rules. I do minimal research before the fact, so I’m focused on the experience of the journey and not anticipating some known destination ahead. I follow as closely as possible the original route of the stream or waterway, honoring sensitive ecosystems where present, but sometimes engaging the creek in a uniquely physical manner, as noted by the muddy boots above. For many reasons, I avoid trespassing, even when every fiber of my being wants to walk into someone’s backyard because I know something good is there, hidden just out of site. I often record sounds and take photos. I take lots of notes, and mostly importantly, I take my time. Although I’m not averse to company, I usually like to do these walks alone, to feel fully immersed in the process of engaging all my senses. And every time, even when I’m convinced there will be nothing, a monotony of development for the miles I plan to follow, I’m always rewarded with hints, clues, and traces of the palimpsest of the hidden hydrology.

It’s something that is present to varying degrees in every city around the world. A common thread we can all connect with, is the burying of these lost waterways, which happens in every city, everywhere in the world. It’s a commonality we all share distinct from culture, geography, and ecology—that of the manipulation of our hidden hydrology and our desire to connect back to these lost traces.

So, find and print out an old map. Sketch a route on a new map that matches some stream, any one will do. Grab a comfortable pair of shoes, perhaps a camera and a sound recorder and you’re set. Drive, bike, or bus your way to that hidden endpoint on the map. Map and explore, and begin to truly see these hidden parts of your city for the first time.

Jason King

Seattle

All photos and maps © Jason King, Hidden Hydrology, 2018

Banner Image: Urban creeks and wetlands flow throughout Seattle, often hidden from view, including here at Licton Springs Park. Photo: Jason King, Hidden Hydrology

Leave a Reply