Scale tension in common in many large cities, where solutions to problems at one scale are considered the cause of problems at another. At what scale should cities then be governed? The answer is simple without being obvious. A city should be governed at the scale of its most painful problem and highest priority.

Could we construct a new image of what the political boundaries of an urban landscape could take shape as? Instead of the hierarchical approach that is commonplace, with cities governed by layers of neighborhood, urban, regional, and state-provincial levels through different electoral or appointed bodies, I propose to approach the problem geometrically, by using the principles of scaling and iteration to demonstrate how fractal geometries can provide solutions to urban scaling politics that layers of governance fail to provide. We will explore a way to resolve political tensions at the municipal level by applying natural, fractal geometry to city boundaries, and that this geometry provides a natural way to govern cities of millions with historical roots of many centuries.

The most significant event in North American urban planning of the past century is the challenge organized against Robert Moses’ plan to build a highway through Greenwich Village in Manhattan. The conflict put a halt to a half-century (or more) of automobile-scale modernisation in cities and started a trend of scaling down government to the neighborhood. Two books on the outcome of this event have massive influence on our perspective of city planning to this day: The Death and Life of Great American Cities, by Jane Jacobs, documents the complexity and liveliness of urban relationships at the small scale, while The Power Broker, by Robert Caro, documents the byzantine system of management and influence that had been constructed by Robert Moses to plan and transform New York City at its largest scale.

I suspect the reason why these books could become so influential, and the conflict of Greenwich Village so widely known, is that the same tensions and conflicts arise in every large city. While the sample size is admittedly small, there is a visible trend in cities that achieve the multi-million population scale to struggle with issues that are scale problems expressing themselves as political conflicts.

Many of these cities suffer, for instance, severe home affordability issues. As an extreme case, the San Francisco Bay Area is governed as a patchwork of small regional hubs and country towns, not the sprawling world metropolis it has become. For the past decade it has received billions, perhaps trillions of dollars of capital flows to its technology companies. As a result, a class of technology professional has become so wealthy that the housing market of San Francisco is becoming exclusive to cash buyers. The traditional wealth-building instrument of mortgages, such as the one that made the wealth of Steve Jobs’ adoptive middle-class parents, has become irrelevant to people whose wealth comes from selling companies to global investors. Large corporations now erect pharaonic new headquarters where they once occupied Jane Jacobsean repurposed office and industrial buildings. The patchwork of municipalities, and the city of San Francisco itself, are fighting tooth-and-nail to preserve by regulatory powers their suburban single-family housing originally intended for a mortgage-driven market, and in the garage spaces of which many of the now gigantic corporations were founded, against the waves of investment capital flowing to them. As a consequence, regional home prices are increasing at an even greater pace, and a counter-intervention against those preservationist regulations are being proposed at larger levels of government to increase regional supply of homes and hopefully break the cycle.

Toronto’s housing affordability challenge is comparable to San Francisco’s. Toronto is governed by competing provincial and agglomerated municipal jurisdictions. This arrangement is the outcome of a multilateral merger of the suburban Edge City around the gridded industrial city that had preserved itself quite successfully from modernisation, and was not coincidentally the home of Jane Jacobs. The conflict between suburbs and center city in Toronto has taken tragicomic proportions with the election of the Ford brothers (champions of the suburban residents) to first City Hall with Rob, and now with Doug as premier to the Ontario Provincial legislature (a competitor for authority over the city and a building historically located within walking distance from City Hall). Exacerbating the political logjam around its tram and subway network expansion, the seam between core Toronto and its suburban ring is the 401, a severely congested 18-lane highway.

The tension between neighborhood preservation and home affordability is in multiple metropolises creating a cycle where regional powers are reasserting themselves through grassroots influence groups such as the various YIMBY movements. Nearly all of them propose, as a solution to the housing development pipeline running dry, a return to regional-scale planning. This takes the form of coercive constraints on the powers of neighborhoods to regulate home building rights, or direct mandates to add more affordable homes in proportion to a neighborhood’s size within the region, with penalties attached for failure. The prototypes for these are the European capital cities of London, then Paris, which struggled with the conflict between local preservation and home affordability decades before North American cities. They have unfortunately not found a successful resolution so far, despite multiple attempts to scale planning up, up to outright nationalization of planning codes.

Scale tension pervades these problems, where solutions to problems at one scale are considered the cause of problems at another. It’s evident that applying more power at one end of the scale produces a balancing reaction at the other end to neutralize that power, and everyone ends up wasting their energies in a cycle that produces no beneficial resolution. Unfortunately there is no political resolution because both positions are correct at their respective scales, and well worth taking a stand for.

The question that should concern us is thus at what scale cities should be governed. The answer is simple without being obvious. A city should be governed at the scale of its most painful problem and highest priority. What makes this simple question create so much complexity is the enormous variation of what constitutes the most painful problem over the landscape, especially large metropolitan world capital landscapes.

Biological systems have no trouble solving for complex landscapes, for instance by repairing small errors in cellular divisions or fighting infections by viruses before they become generalized, while simultaneously the larger animal flourishes in its ecosystem by complex adaptation and cooperation. Fractal geometries and boundaries are essential to this success. Could we imagine such a geometry for a city?

The problem to be solved is to create a geometry of the metropolis that is simultaneously local and regional, that allows local communities to grow through their own specific urban generators while it remains simple to launch and plan projects at the regional scale. The divisions have to be clear enough internally that people can easily understand how they work, thus excluding the layering of levels of governance and bureaucracies.

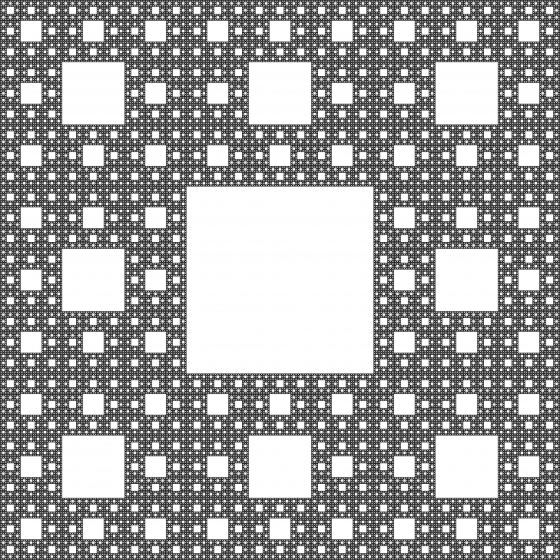

An object that describes such a geometry is the Sierpinski Carpet.

The Sierpinski carpet is a fractal construct that has structure at infinite levels of scale and can therefore solve problems that occur at the biggest and smallest scales, providing unusual applications with devices such as antennas. Could this be applicable within a large modern metropolis? It could suggest that a regional metropolis has grown around smaller existing communities and towns, each with their own separate and contrasting scale, and harmonizes them into a coherent whole at their boundaries. It would be a fractal, perforated city.

Let’s consider the intuition behind this. We are familiar with hierarchies in cities’ networks, such as arterial roads and access roads, or regional transit lines fed by collector networks. This makes the centrality of cities fractal, since time and distance to reach any given point depends on the shape and hierarchy of the network and not the abstract geometric distance of bird flight. We know the feeling of being in the center of a large nature preserve and feeling the city fading away, despite perhaps having walked from downtown. The shape of networks shapes our experience of urban space, and these networks are fractal.

Has there ever been an experiment with this kind of fractal landscape? I believe all unresolved local-regional standoffs are instances of such an experiment. For my last assignment as a graduate student of urban planning in Paris I was fortunate to serve as an intern on the planning staff of one Paul Delouvrier’s (planner of the regional express system, the Robert Moses of Paris) great projects for the Paris region, the New Town of Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines. The city has since its founding been a microcosm of the local-regional conflict.

Local government in France is notoriously entrenched, the Ile-de-France region being divided into over 1200 communities, roughly one third of them creating the 10,000,000 people Paris metropolis. Planning a world capital with 1200 mayors, all out to protect their local community and thousand-year-old identity, has to this day been achieved by layering multiple superimposed regional authorities, some elected, some administered by boards, that have fought each other in party-line turf wars and become an abstraction to the citizens they are remotely accountable to. Whenever things achieve complete irrationality the national state under the president, or sometimes Emperor, directly intervenes and bypasses local administration to resolve scale issues.

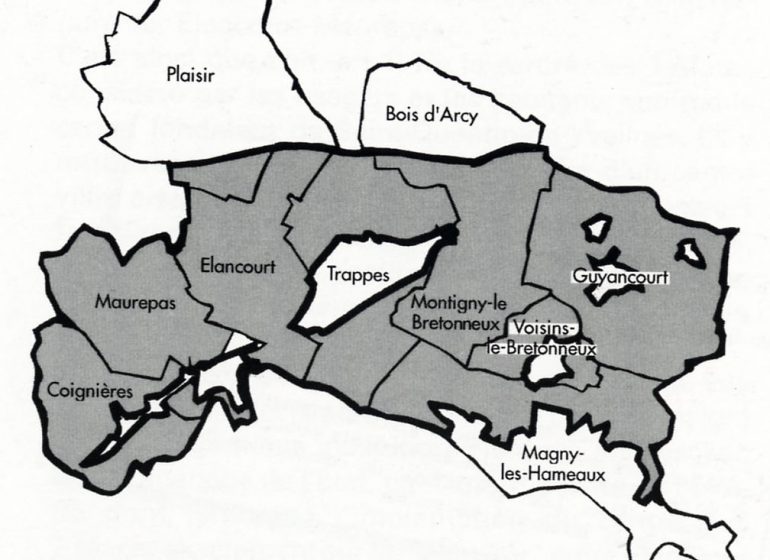

The city of Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines was a response to the post-war housing affordability crisis of France’s capital. The original territory, on the outskirts of the urban area just south of Versailles, was a sleepy agricultural country with one small town and a handful of villages surrounded by large farming estates until the state launched its program of new towns in the late 1960’s. Because the farming estates were concentrated in the hands of a few large landlords, the state considered them easy to acquire and develop into a city with a population that could act as a political balance to the Parisian core (it was planned for as many as half a million residents). A state-owned developer, EPASQY, was created to develop and commercialize the new town, and a special regime of planning regulations was imposed by the state around the existing town and villages, while preserving the local building codes within them. This territorial organization had the form depicted below.

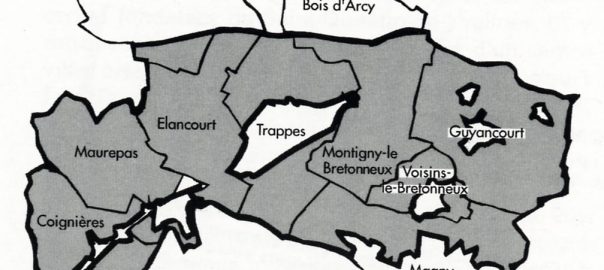

The gray area was the territory controlled by the development company. The white pockets were the town of Trappes and the other villages and hamlets of the area, which maintained nominal political autonomy. The tragic aspect of this organization is the superposition of the historical community boundaries through the structure. The commune is the basic element of local governance in France, defined and delimited during the French revolution and static ever since.

Instead of creating a new commune for the new town, the suburban commuters resettling from Paris became citizens of the existing town and villages, outnumbering the existing citizens with which they had no shared historical interests. In one fateful election year every mayor was swept from office and replaced with more politically-savvy migrants from Paris, who quickly acted to block the plans of the state developer and scale them down to what it is today, a suburban city of around 150,000 made up of 7 semi-autonomous and politically antagonistic communities now struggling to solve integration problems that were to be resolved by the development company.

Because the boundaries of the cities did not match the boundaries of the communities that lived in them, some very ancient (though quite small) communities disappeared, the metropolitan community did not achieve its goal of resolving demand for homes and decentralizing the capital, and a new system of antagonistic suburban towns rose in its place.

The nature of fractals suggests that we should see the same pattern across the territory as we decrease the resolution of our observations. In fact, a visitor to the Paris region could be easily persuaded by the necessity of preserving its local communities, some of which have had a distinct existence since before the middle ages (one town, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, has the claim of being the birthplace of the French kings, with castle and cathedral to go along), from regional growth demands.

Some tourist-favorite neighborhoods are outright alien, such as the skyscraper district of La Défense, an attempt by the state to create a business cluster decked on top of a three-story rail station and which landed like a UFO on the boundary between two existing communities. That neighborhood has grown in a legal gray area under exceptional administrative status granted to it by presidential decree.

Other communities have not enjoyed political autonomy since Haussmann’s reforms, but continue to exist in fact and as special planning zones. The village of Montmartre is physically remote by rising above the center city in height, not only by being hard to access by road. These distinct planning processes are sometimes abolished, sometimes brought back, but as with any exception they make governing a more difficult and conflict-prone task.

The solution to tension within Greater Paris and its many communities would be to create a perforated fractal metropolis, with special historical communities and their distinct planning processes existing autonomously within it, but not concerned with regional-scale issues such as infrastructure, economic competition or home affordability, that being solved by the metropolitan-scale community.

The most important of these inner communities, and the one most people recognize as Paris, is the historic core of boroughs 1-12, where all the landmarks and iconic architecture are found. This area has developed a tourism-centric economy that requires a planning process focused on strict preservation of the urban fabric, or as Parisians call it, a museum-city. Quality of life and reducing the impact of traffic and tourist activity dominate its politics.

Beyond that circle begins metropolitan Paris, a space centered along the two ring expressways, whose community faces entirely different challenges and priorities. Scalability, not historical preservation, is the major concern, with transportation, home affordability and ecological harmony of residential development as the major problems to be resolved.

If Greater Paris were redrawn as a fractal, then alongside major historic towns such as Cultural Paris, Versailles, and St-Denis, the territory could be perforated by a constellation of villages and perhaps some entirely artificial and experimental communities. At the fractal boundaries of the metropolitan city of Paris would exist preserved historic communities as well as special-purpose mission-based cities, such as La Défense or the community of Eurodisney, whose unconventional urbanism and unorthodox governing institutions preserve the economic vitality of the region.

A fractal territorial structure of thousands of communities cannot be made by legislative act (the debates alone would be endless), it must be an emergent outcome of autonomous communities exchanging parts of their territory until they have achieved an equilibrium. For this the legislators must give up defining the boundaries and instead define a process by which communities are formed and grow out of other communities. Dividing a community from a city must be as quick and expedient as extending a city to a new boundary reflecting its greater scale. Preserving a quiet community from a booming residential market must be as accepted as constructing whole new neighborhoods for hundreds of thousands of new households on reclaimed industrial or commercial zones.

With Paris serving as a model of regional complexity fitting the proposed geometry, we can easily project the same geometry onto Toronto and New York and arrive at similar conclusions. Had Greenwich Village remained an autonomous community (it has an urban grid oriented differently from Manhattan’s because of its autonomous past) then Robert Moses would have gone around it, and perhaps a political operative such as him would not need to exist if New York’s city government had scaled large enough to lead regional capital spending projects. Toronto’s suburban Edge City would be empowered to deal with the consequences of its automobile-centric path without clashing with the preservationist and localist culture of the center city.

Institutional health can come from specializing on a shorter list of priorities, but regional complexity itself cannot be simplified or shortened. It requires complex pattern formation to resolve, and we now know that complex patterns can be produced through the iteration of simple geometric rules that produce fractals. The political landscape can itself be fractal if this geometry becomes part of our common knowledge. With each fractal city able to focus on its unique priorities the friction generated by scale conflict would no longer hold back necessary policies, from preservation of historic or cultural identities at one end of the scale, to resolution of demographic, ecological and technological pressure at the other end. If we could perceive the fractal boundaries of the landscape, then energies that we invest today in debates, public activism and moral arguments over issues that are defensible on different sides of these boundaries could be redirected to improving our communities.

Mathieu Hélie

Montreal

Leave a Reply