The right of people to freely move, interact, work, and associate should not be at the expense of wildlife to thrive. It should complement their right to a clean, safe, and productive environment.

The most recent development in this quest for an interlinked, faster, and efficient movement of people and goods within the city is the construction of a four-lane thoroughfare aimed at connecting Nairobi’s Westland area and the iconic Jomo Kenyatta International Airport. The 62 billion Kshs (about 6.2 million USD) expressway activated by the China Road and Bridge Corporation will also serve residents of Mlolongo and fasten the time taken to reach the international departure station. The construction follows a green light from the country’s National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA), which conducted an Environmental and Social Impact Assessment of the then proposed urban infrastructure. Once completed, the expressway will ease the flow of traffic as travelers will not have to go through the city’s central business district to catch their flights. However, the environmental harm caused by this project is large-scale and somewhat irreversible. The environmental and social impact report of the enhancement of road A104 from James Gichuru road junction to Rironi indicated that contractors needed to clear trees and other vegetation for the multimillion-dollar project to take place, resulting in loss of habitat and biodiversity. Other negative environmental impacts of the road construction outlined in the report included contamination of soil and water resources, soil erosion at road reserve, and increased waste generation.

The environmental and social impact report of the enhancement of road A104 from James Gichuru road junction to Rironi indicated that contractors needed to clear trees and other vegetation for the multimillion-dollar project to take place, resulting in loss of habitat and biodiversity. Other negative environmental impacts of the road construction outlined in the report included contamination of soil and water resources, soil erosion at road reserve, and increased waste generation.

Road developers of the Nairobi Express way from Mlolongo to James Gichuru earmarked sections of vital public green spaces like Uhuru Park and Nairobi Arboretum, and trees that host birds around Westlands and Nyayo stadium roundabouts, for clearance. In a set of conditions provided by NEMA in March 2020, the authority advised the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) to mitigate the damage by planting trees in all affected spaces. The CRBC was also expected to clean the areas of the Nairobi river over which the road would cross. NEMA did not, however, give clear communication on whether the Chinese contractor should replace the mostly indigenous trees with similar ones. My common observation over the years has been that road builders often replace indigenous vegetation with exotic grass and trees species, and ornamental plants.

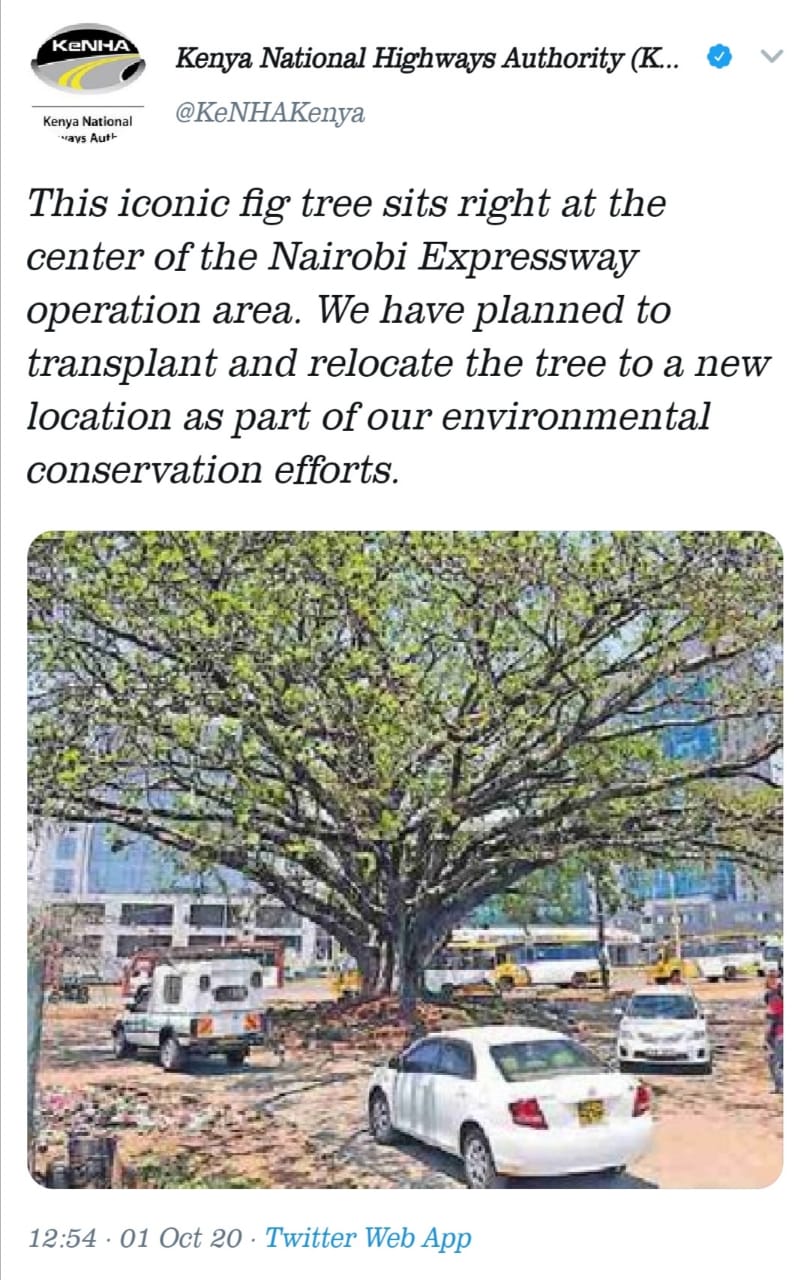

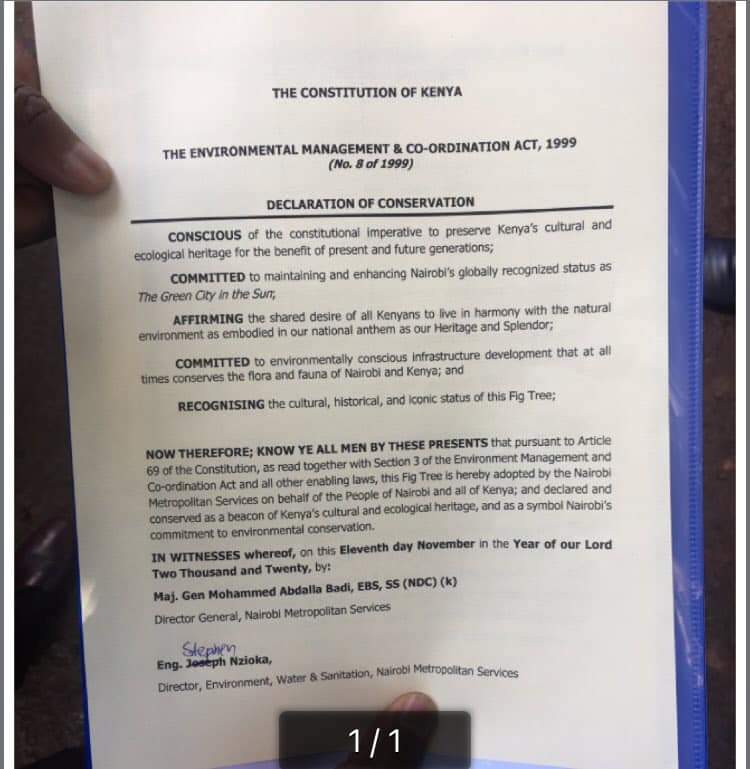

To the astonishment of conservationists and concerned residents of Nairobi, the Kenya National Highway Authority (KeNHA) had confirmed last month that it would uproot an iconic fig tree that that has been sitting pretty at the crossway between Waiyaki Way and Mpaka Road for over 100 years. This news elicited demonstrations from groups of environmental activists, calling the government to consider biodiversity in its quest for modernization of the transport systems. In a news conference held on Wednesday this week, the director general of the Nairobi Metropolitan Services (NMS), General Mohammed Badi, assured the public that the iconic tree will stay put in its current place. While visiting the site where the gigantic tree exists, General Badi said he was working on a Presidential declaration to preserve the famed tree.

The spectacular tree, estimated to be the height of a four-storey building, will be adopted by the Nairobi Metropolitan Services. The Nairobi boss further instructed the environmental department to erect a fence as a protection measure to ensure Nairobian continue to enjoy its presence. He also vowed to “recover Nairobi’s lost green spaces”. While this breathed a sign of relief to many and a clear show of a battle won, many other green areas in the city have already gone under the wrath of builder’s axe and irreversible damage witnessed.

Growing up, I was always welcomed to Nairobi with extensive roadside green spaces full of trees and life. The stretch between Uthiru and Westlands had well-preserved tree lines that truly depicted Nairobi as the Green City Under the Sun. It was always refreshing to have this feeling before you go deep into the noisy and busy estates that form the city. The story of the Nairobi green reception area has since changed. The expansion of the Nairobi-Nakuru

Highway has entailed massive vegetation loss with minimum to no replacement done so far.

Such unprecedented habitat fragmentation has a far-reaching contribution to biodiversity loss. Isolation of animal and bird species often makes them vulnerable to predation. Displaced animals may also find it hard to adapt to new surroundings. Woodland-dependent species of animals may find it difficult to settle in fragmented patches of landscapes. Subdivision of breeding areas also disrupts natural mating patterns, which eventually affects the flow of genes within a species. Residents of Nairobi are denied their fundamental right to access to a clean and healthy environment when ecosystems are destroyed or fragmented, as they are unable to function optimally.

Nairobi’s river ecology is not spared. The Express Way will traverse over rivers Nairobi and Ngong. In its impact assessment report, NEMA indicated that the road contractor should ensure that sections of the river over which the road will pass are cleaned. While this sounds like a glimpse of the right thing to be done, it is unclear whether the “cleaning” process will mitigate all the harm caused by construction on the rivers’ structure and functionality.

Nairobi’s population, which is about 4.4 million people, is expected to double in the next 50 years. The projected increase dictates the need to conserve the few green spaces available in the city. Conservation organizations such as the Kenyan Youth Biodiversity Network, Wangari Maathai Foundation, Natural Justice, Wildlife Direct, and the Green Belt Movement have been at the forefront of opposing the construction of the expressway as initially planned, citing the adverse impact on the city’s ecological spaces. In June 2020, a petition was filed in court under the umbrella of the Daima consortium, propelling NEMA to adequately involve the public before approving the construction of the expressway.

An initial statement released by the government in 2019 indicated that Uhuru Park, the largest, historical, and most preferred public spaces, was to lose about a 23 meters thick stretch to the road. We will keep a keen eye on it to see if the current construction will tamper with this central park. Our freedom fighters and environmental defenders like Professor Wangari Maathai fought to have these spaces protected from degradation, grabbers, and encroachment. The milestone makes Uhuru Park a national symbol of freedom and the power that people have in standing for their ecological rights. We must fight to ensure that the legacy is maintained and that future generations enjoy their right to the ecosystem services provided by these spaces.

The four million Kenyans who currently live in Nairobi depend on forested areas such as recreational parks to relax, appreciate the city’s beauty, and catch some fresh air. Nature lovers find green spaces such as the Nairobi Arboretum, City park, Karura forest, and Ngong Road forest perfect hideouts and ideal for cycling, birdwatching, and meditation. Living in one of the busiest, hence polluted, cities in Africa, these green spaces absorb a considerable amount of smoke, dust, and other harmful air particles.

The $467M Southern Bypass that left sections of the once pristine Ngong Road Forest cleared is another visible case of how Nairobi lost some of its urban biodiversity. Ngong Road forest, a once continuous and thriving urban natural ecosystem with endless varieties of trees and a host to a myriad species of birds and animals, was fragmented into five sections. The forest is the only true indigenous forest in the county and hosts the near-threatened African Crown Eagle as one of its key bird species. There have been efforts by multiple role players to recover the tree cover lost due to the construction of the Southern Bypass. However, the conversion of interior habitats into road-edge habitats means the ecosystem can no longer function as efficiently as it used to. The 30 km road has had visible habitat fragmentation that points to an immediate impact of wildlife dislocation and isolation, and an undocumented probability of local extirpations.

Development that is informed by the density of cars in the city is unsustainable. Nairobi’s population will continue to steadily rise, creating an endless need for additional infrastructure and other social amenities. Young people, together with other stakeholders, should help the government urgently explore mechanisms of improving road transport using the available space, without the need to put pressure on existing green spaces. Contractors must urgently prioritize innovative ways of maintaining the integrity of green spaces, reducing dependency on private cars, and incorporating sustainability into road plans. It is becoming increasingly important for commuters to consider carpooling to access work, recreation, and shopping. Fewer cars on the road will always reduce demand for the expansion of road infrastructure. I encourage the use of more sustainable modes of transport, such as cycling, that do not need large spaces of land.

The construction of a standard gauge railway (SGR) right through the Nairobi National Park is another clear illustration of how the government of Kenya has its priorities twisted. Nairobi National Park, an extensive natural space of its kind in the world is now battling a myriad of challenges, including invasive species. It is estimated that the park lost about 100 acres of conservation land to the multibillion gigantic transport project. This is a considerable amount of conservation land to lose, considering the park is only 117 km2. The already vulnerable ecosystem was divided by the railway line into two sections. The deliberate disruption of the continuous flow of the park poses a threat of confining animals in certain areas, an element that is likely to promote inbreeding and ecosystem imbalance. Reducing the size of the park will escalate human-wildlife conflicts.

The Environmental Impact Assessment report, conducted only after a public outcry, did not adequately cover the potential ecological impacts of the project in the park. Efforts by environmentalists against the railway line passing through the park were unsuccessful. One of the most memorable moments in my life was taking a signed petition to the national parliament of Kenya and the headquarters of the Kenya Railway Corporation. We also held demonstrations to urge the government to consider re-routing the railway line. All in vain.

The right of people to freely move, interact, work, and associate should not be at the expense of wildlife to thrive. It should complement their right to a clean, safe, and productive environment. Nairobi’s urban infrastructure development has proven that political priorities are more economical than ecological, which could affect the city’s functionality in the long term. The County Government of Nairobi should evaluate their infrastructural development priorities and consider the sustainability of its green spaces.

Kevin Lunzalu

Nairobi

Leave a Reply