Introduction

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

There has been what seems like a lot of work on Nature-based Solutions.

There has been great enthusiasm among NbS professionals for “mainstreaming” NbS into urban practice. We generally mean one of two things when we say mainstreaming NbS: (1) making NbS more widely known in the general public (like, say, “climate change” is…maybe); and (2) making NbS the default or common practice among urban professionals. The two are perhaps related, but the audiences for such social change are not exactly the same. Plus, NbS professionals are often a little vague about which element of “mainstreaming” they are talking about.

As contributor Harriet Bulkeley says: what does it mean to become mainstream?

The answer seems simple, until we actually start talking about it.

The mainstreaming we need may be an old idea, not new one: reconnecting humans to nature.

Now, this is certainly a matter of “communications”: tactics about how to effectively spread the good word about the cultural and environmental importance of NbS. This is important. But it is not only communications. It is also a matter of how the frames we use for indicating “NbS” reflect deeply on what we believe is important in weaving environmentally friendly and effective design into notions of science, society, and place: what NbS installations do; how they fit into the social fabric; the equity challenges of who gets to choose and benefit; their direct economic benefits; how NbS designs occupy a fizzy boundary between ecological and social value and meaning.

What are the wicked problems for which we need “solutions”? They are found embedded in both social and environmental challenges, which are difficult to disentangle. Maybe they should remind entangled, so we an seek and find rich cross-sectoral solutions and then find language to talk about them with everyone.

As contributor Gillian Dick points out, there is a park near her house with a road through it. The park has provided benefits since long before there were called NbS. The road is counted in the government’s books as an economic benefit. The park just counts as a negative because the only thing they count in the budget is the maintenance cost, not the harder-to-quantify social and environmental benefits. Indeed, as several contributors point out, across many years and nomenclatural evolutions, much of what we need is to re-maintream an older idea of human connection to nature.

What are the wicked problems for which we need “solutions”? They are found embedded in both social and environmental challenges, which are difficult to disentangle. Maybe they should remind entangled, so we an seek and find complex solutions. These are questions that firmly reside in the emerging New European Bauhaus mission.

So, OK, we asked 33 people professionally engaged with NbS in one way of another: from scientists to practitioners, from grant makers to artists. What do you mean by “mainstreaming NbS”? And, if the goal is to mainstream NbS in the way you desire, what will it take to get there?

This roundtable is a co-production of Network Nature PLUS (in which TNOC-Europe is partner), which is funded by European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 887396; and by by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) under the UK government’s Horizon Europe funding guarantee under grant No 10064784.

This roundtable is a co-production of Network Nature PLUS (in which TNOC-Europe is partner), which is funded by European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 887396; and by by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) under the UK government’s Horizon Europe funding guarantee under grant No 10064784.

Loan Diep

about the writer

Loan Diep

Loan is a researcher in environmental studies. Her work is centered on the development of cities that are green and inclusive of communities, most particularly those trapped in marginalizing systems. Her PhD focused on green infrastructure for rivers in informal settlements of São Paulo.

One of the powers of NbS resides in the fact it can give us clarity on where the greening and the “right to the city” agendas might be in conflict.

When the concept of Nature-based Solutions (NbS) started to popularize among IUCN and its circles in the 2010s, many asked what new doors it could possibly open that had not already been pushed by its predecessors “ecosystem services”, “green infrastructure”, “ecosystem-based adaptation” (to name a few, in case they have already been forgotten…!).

Framing NbS as an “umbrella concept” by the big players was a smart move that essentially helped sweep up all the other ones that had already done the hard work of opening up the way towards a greener societies. It has worked pretty well. NbS has already conquered many academic, governmental, non-governmental, and other public and private spaces of most regions of the world. But certainly not all…why?

For a start, the idea of “widening public acceptance” of the NbS concept ― of any concept in fact ― is a misconception, and it surely should not be the goal. The notion of public acceptance is one that carries heavy assumptions. It conveys the idea that the public, as a single homogenous entity, is out there waiting to be convinced (controlled?), largely by those in charge “above” and/or the “experts”. It is a famous rhetorical strategy to portray the public as unaware, unknowledgeable, not interested, or sometimes rebellious, and where the means are justified under the putative argument that “it is for society’s own benefit”. Many have used it to push for the NbS agenda.

And there we went again: the usual greenwashing suspects entered the game and integrated NbS into the same dualistic and hierarchical structures that create exclusionary patterns. These dynamics, we know it, clearly emerge where greening agendas are pushed by governmental institutions supported by big financers, and lead to evictions, land grabbing, gentrification and displacements. Nothing we don’t know. Yet, it keeps happening.

Vila Nova Esperança is a perfect example of the power of international green discourses over everyday lives, and which can be particularly damaging for those living on the edge (metaphorically and not). Because Vila Nova Esperança settled in proximity to an environmentally protected area, this community living on the margin of the city of São Paulo has been threatened with eviction. To resist, their community leader engaged in a series of initiatives to prove the community’s alignment with environmental values (Photo). This helped the community build a counter-narrative, a tool for resistance.

While the political visibility that these actions attracted has enabled Vila Nova Esperança to survive, other communities have not met the same fate. Green projects supposedly aimed at helping the most vulnerable, have commonly ended up creating more issues because of the set of assumptions they are based on in relation to human-nature relationships. Dobson’s Ecological Citizenship theory reminds us that environmental rights and duties are disproportionately owed in society. In its mainstreaming quest, NbS first needs to resolve such non-reciprocity.

If we have learned anything from attempts to mainstream other concepts, it is precisely that mainstreaming can be the enemy of transformational change. If mainstreaming NbS comes with a process of letting the usual suspects in power to (re-)appropriate concepts precisely developed for the purpose of changing what “mainstreamed” concepts failed to address, we are simply repeating history.

NbS helping us put a finger on multi-scalar politics could be its greatest strengths. One of the powers of NbS resides in the fact it can give us clarity on where the greening and the “right to the city” agendas might be in conflict. If NbS brings nuances to dualistic worldviews, it can break barriers that place people and nature in opposition. Only then we will be in position to explore the innumerable possibilities of truly integrating them. Rather than seeking wide acceptance of the concept, understanding its resistance might be where we learn from it the most, dig into the heart of the problems, and finally move forward.

Paola Lepori

about the writer

Paola Lepori

Paola Lepori is a Policy Officer for Nature-based Solutions at the European Commission, DG Research & Innovation. Her core professional objective is building alliances to trigger transformative change towards an inclusive nature-positive future.

In the quest to mainstream an idea and turn it into a default option on the ground, each of us needs to engage with those within our reach, speaking their language, understanding their narratives, needs, and concerns, creating alliances and partnerships, cultivating new ambassadors.

When I try to explain what I do for a job―and it’s never easy because the role of policy officer is somewhat hazier than more tangible professions like architect or farmer—I usually mention that part of it is contributing to “mainstreaming Nature-based Solutions in policy and practice”.

My understanding of “mainstreaming” reflects the Cambridge Dictionary definition: “the process of becoming accepted as normal by people”. Where it gets complicated is in the how to make that happen. What concrete steps lead to something becoming accepted as normal by people and who are these people whom we want to accept nature-based solutions as normal? Lastly, how do we measure success?

I know this roundtable includes brilliant contributors who are going to adopt a much more scientific and grounded approach than I could ever hope to achieve, so I won’t delve into specific mainstreaming strategies and the theoretical approaches behind them. My starting point is imagining and visualising a world in which NBS are “mainstream”.

Imagining a certain kind of world is the very first step towards bringing it into existence. So, I imagine cities where the green, and all the colours that beautifully dot the green, are widespread and accessible regardless of the social stratification of urban areas. Cities where rivers and streams are not bridled but can regain their space and follow their natural courses, truly integrate natural features of the urban landscape rather than constrained sources of potential danger. Cities that are not exclusively human settlements, but where life forms other than us can reclaim space and coexist comfortably, rather than at the margins; and an urban built environment that lives in partnership and symbiosis with vegetation.

While this image seems to convey just an aesthetic idea, it’s actually the visual representation of an urban landscape in which nature-based solutions—which embody an alliance on equal footing between nature and human societies that is not based on exploitation but on mutual benefit and on re-internalising the notion that human beings are, in fact, part of nature—help us tackle a myriad of pressing and even existential challenges that we face today in our city life, mostly due to the combined and interdependent effects of human-induced climate change and biodiversity loss.

This visualisation represents the end goal. How do we get there? The grand objective that seems so far away it’s almost unreachable can only be achieved by breaking it down into smaller components and fostering collective efforts where each contributes according to their skills, expertise, inclinations, and network.

Where can I hope to achieve the most impact? How do I prioritise where to invest my energy? Given my access to EU policymaking in different fields, I’m in a privileged position to raise awareness of nature-based solutions within my organisation—this big and complex public administration that serves half a billion people in Europe—with all the firepower provided by the knowledge produced by the NBS community with (but also without) EU funding, with the ultimate goal to create an EU-level policy and regulatory framework that is conducive to the uptake at the scale of NBS. (In this, I’m encouraged by the words of former EU Commission climate chief Timmermans who said that “we will promote nature-based solutions as much as possible”).

My point is that in the quest to mainstream an idea and turn it into a default option on the ground, each of us needs to engage with those within our reach, speaking their language, understanding their narratives, needs, and concerns, creating alliances and partnerships, cultivating new ambassadors.

Mainstreaming NBS may seem like a vague and far-away objective but it’s already happening and if I can add one last word, ultimately, I don’t even care if people call it NBS; my main concern is seeing the future I describe materialise.

DISCLAIMER: These views are expressed in a personal capacity; they are not meant to represent the official position of the European Commission.

Kassia Rudd

about the writer

Kassia Rudd

Kassia Rudd joined ICLEI in March 2022 and plays a leading role in communicating ICLEI’s work on nature-based solutions. Kassia leads strategic communication for multiple EU projects committed to furthering sustainability and justice via urban greening, leveraging her professional and academic experience in public health, community outreach, sustainable agriculture, and restoration ecology to render project results accessible, engaging, and meaningful to a broad audience.

It is corny, but mainstreaming requires working NbS into the tapestry of a city or region. It can’t be only one thread or motif―NbS must be woven into everything. Cities like Quito can help us figure out how best to get there.

To answer this question, I have to start with the definition of mainstreaming. What do we mean by the term, and do we all mean the same thing? For me, mainstreaming means that an idea or process has become the default, not the exception. That it is interwoven into everything we do. For Nature-based Solutions (NbS) to be mainstreamed, they cannot be extra, additive, or nice to have. Rather, NbS components must be integral to urban and regional planning, and key components of all construction plans. Increasing awareness is essential because as many have said before me, to change something, we first need to name it. For behavior to change, people must understand, value, and feel empowered with the knowledge, skills, and monetary resources necessary to integrate NbS across the planning and political landscapes.

Based on my work with cities, effective mainstreaming generally involves (1) education at all levels (community, primary, university, professional); (2) practitioner accountability via integration into standards and policy; and (3) financial incentives such as equipment/tax rebates or grants.

These components operate at the individual, community, and governance levels. Effective mainstreaming cannot rely solely upon single initiatives that live or die by champions but must instead provide the scaffolding (education and funding) for grassroots success, but also integrate top-down pressure via political mandates and standards. This is seen again and again in the school garden sphere, where an individual teacher invests time and energy in a garden, but there is no one to fill any gaps should the individual retire or simply experience reduced capacity. We need champions, but we need them to operate as a network supported by a facilitating political and financial framework.

I am smiling now because I recently visited a city that is turning the tragedy of the champion story on its head. Quito, Ecuador, is a city of Champions. The cast of characters includes Yes Innovation, a dedicated duo (individual level) furthering innovative architecture and urbanism via NbS; the residents of the San Enrique de Velasco Neighborhood (community level) who gather regularly to discuss greening their streets; and the office of the Secretary of the Environment, City of Quito (individual/governance level). CLEVER Cities (financial incentive), a Horizon 2020 project supporting the integration of NbS into urban planning helped bring these actors together but these champions worked together to integrate NbS into the new local blue-green ordinance (accountability/governance level). More recently, they wrote a Spanish language guide to NbS for the city of Quito (education), which will soon be translated into English. While the CLEVER Cities project is ending this November, many of the resources guiding NbS Mainstreaming can be found on the CLEVER Guidance, and will also be permanently housed on the NetworkNature resource platform.

At their core, NbS are a holistic approach to a variety of social, economic, and environmental problems. Using NbS, Quito is actively generating benefits for communities such as flood management, water conservation, and protecting biodiversity. While important, any one piece of Quito’s approach would not be mainstreaming, but because Quito is working with the community, has local businesses involved, and is integrating NbS into policy, slowly but surely, NbS is on its way to being normalized. It isn’t the norm yet, as evidenced by the recent destruction of a community rain garden along a seldom-used and often-flooded dirt road in favor of a non-porous pavement. Despite setbacks such as this, Yes Innovation, in partnership with the neighborhood and Secretary of the Environment, are mainstreaming NbS in their own sphere, and reminding the city at regular intervals of the positive impact local NbS could have on recurrent flooding and community cohesion.

While there is still a long road ahead for Quito, substantial change has already taken place. There is awareness at the community level that NbS can provide solutions to local challenges and improve quality of life. Community interest is a key component of mainstreaming, and essential for innovative NbS implementation. At the end of the day, NbS works best when communities decide what they need and how they want to get there, effectively becoming living labs for non-conventional and inspiring NbS.

“What do [future generations] have to learn in order to take care of the planet? We want to generate awareness so that [future generations] can take care of the earth. We would like everywhere to have this policy. The planet is calling, and we want to answer this call” -INEPE Director, Quito, Ecuador.

This is true for all of us, yet awareness is only one step. It is corny, but mainstreaming requires working NbS into the tapestry of a city or region. It can’t be only one thread or motif―NbS must be woven into everything. Cities like Quito can help us figure out how best to get there.

Laura Costadone and Bryce Corlett

about the writer

Laura Costadone

Dr. Laura Costadone is an Assist. Research Professor at Old Dominion University for the Institute for Coastal Adaptation and Resilience. Laura brings her expertise in co-design and co-create pathways to uptake and implement urban sustainable development goals by engaging directly with municipalities, practitioners, decision-makers, and citizens.

about the writer

Bryce Corlett

Dr. Bryce Corlett, PE, has nearly 15 years of diverse experience in the climate change arena, ranging from identifying sea level rise acceleration along the US east coast to discovering an Arctic current to strategically guiding local, state, and national organizations through climate adaptation, wetland, beach and shoreline restoration, and water/sediment quality analyses.

Several critical obstacles must be overcome to operationalize NbS at a scale that can reverse the degradation of natural resources and provide an adequate level of climate change resilience.

The urgency of implementing nature-based solutions (NbS) is higher than ever, especially in coastal areas where cities consistently face growing challenges. Coastal cities must build resilience not only against increasing extreme weather events, such as floods, droughts, storms, and urban heat island effects but also against sea-level rise. Although these challenges have global origins, their impacts are acutely experienced at the local level, requiring local governments to take a leading role in devising and executing adaptation strategies. Despite notable research progress demonstrating how impactful NBS can be in addressing the biodiversity and climate crisis, critical obstacles persist, hindering the translation of scientific knowledge into practical projects on the ground.

The scope of our work at the Institute for Coastal Resilience and Adaptation is to help strengthen resilience and adaptation in underserved local communities. Here in Virginia, as in many other places, adaptation choices are often dictated by local priorities and capacities. Yet, the implementation of NBS is often still limited by the inherent preference for gray infrastructures. Based on our experience, several critical obstacles must be overcome to operationalize NBS at a scale that can reverse the degradation of natural resources and provide an adequate level of climate change resilience.

In coastal cities, the growing risk of flooding posed by sea-level rise provides opportunities for proactive planning at the local and municipal levels. However, it also presents the formidable task of prioritizing among numerous pressing concerns. As a result, planning efforts in response to climate change tend to be either deficient or inadequate due to the significant challenges that emerge when attempting to advance climate adaptation while simultaneously addressing other competing priorities and agendas. Local decision-makers need to optimize budget allocation by making targeted investments, and cost-effectiveness remains a key driver of their decisions.

As a research extension institute, one of the initial requests we receive from local government officials and regional land managers is for more comprehensive cost-benefit analyses to justify the implementation of NbS projects. To address this need, one important step we are taking is to identify and quantify the tangible and intangible ecosystem services and benefits that arise from the implementation of NbS. Developing a robust methodological framework that can be applied from the design phase to account for the monetary value of ecosystem services, including recreational services, urban heat island mitigation, nutrient flood reduction, and biodiversity, is critical in mainstreaming NbS into urban practice.

Regulatory and financial limitations are also significant hurdles that impede the implementation of ecosystem-based projects. Government jurisdictions, particularly in coastal areas, can be intricate and overlapping, requiring integration across various government levels, extensive involvement of stakeholders, consensus on perceived risks and practical solutions, and policies that support desired actions. There is an urgent need to implement soft policy instruments to facilitate the process of mainstreaming nature and biodiversity into all aspects of the city’s urban planning.

Promoting a different approach to support sustainable urban development might not be enough. We also need to address a critical question: Where can we integrate nature into highly developed urban environments? In urban areas, space is often limited, and in coastal urban areas, the lack of room to migrate to higher ground as sea levels rise exacerbates the problem. To tackle this challenge, we will need to make some trade-offs, in some cases, give up space, upgrade existing infrastructure, and consider hybrid solutions for projects such as transportation, redevelopment, housing, water, and sewer. To transition to governance more suited to NBS mainstreaming, we need transformational changes that begin with cultural values, economic mechanisms, infrastructural, and technological systems.

Takemi Sugiyama and Neville Owen

about the writer

Takemi Sugiyama

Professor Takemi Sugiyama is the leader of Healthy Cities research group in the Centre for Urban Transitions. Building on his background and research experience in architecture, urban design and spatial/behavioural epidemiology, he explores how urban form (building, neighbourhood environments) can be modified to encourage active living and enhance population health.

about the writer

Neville Owen

Professor Neville Owen is a National Health & Medical Research Council Senior Principal Research Fellow, Head of the Behavioural Epidemiology Laboratory at the Baker Heart & Diabetes Institute, and Distinguished Professor in Health Sciences at Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia. His research links urban-environment attributes with physical inactivity, too much sitting, and risk of developing diabetes and heart disease.

A concerted effort between research, advocacy, and government sectors is essential to overcome the barriers and to enable NbS transitions to be widely adopted and implemented.

Coordinated action by researchers, advocates, and policymakers can drive transitions to Nature-based Solutions: tobacco control in Australia is a salutary precedent

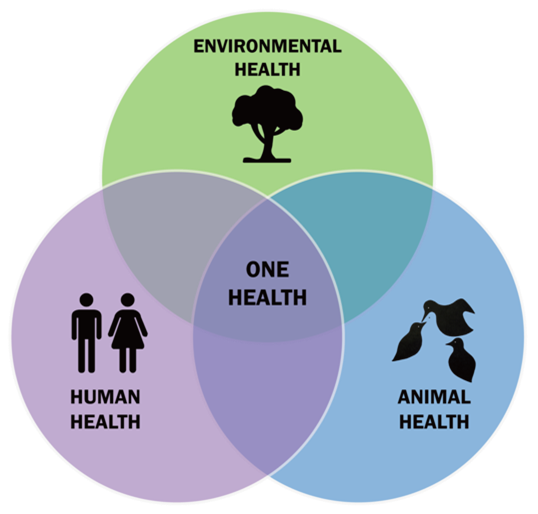

The increasing prevalence of chronic diseases and the interrelated need for actions on environmental sustainability are two of the major challenges that our society is facing today. Chronic diseases (e.g., type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and major cancers) are the biggest killers, accounting for three-quarters of all deaths worldwide (WHO, 2023). They are influenced significantly by, along with other causes, physical inactivity, and air pollution (WHO, 2023). It is also highly urgent to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to limit further global warming.

“Healthy Cities” provides an umbrella set of potential solutions to address these issues (Giles-Corti et al., 2016). A primary target in the promotion of healthy cities is to change how people move across cities, in a context where urban development continues to depend on cars for transportation. Under the global trend of urbanisation, cities expand horizontally, with large segments of the population living in sprawling urban conurbations. The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have accelerated this trend due to more people working from home and requiring more space at home (Sisson, 2022). Urban sprawl and the fossil fuel demands of private motor-vehicle transportation (all too easily construed as reflecting individual consumer preferences and discretionary lifestyle choices) continue to drive major threats to human and environmental health.

Urban-built environments can be highly resistant to change for multiple and complex reasons, including challenges to entrenched economic interests, complex dealings with many stakeholders, and large-scale expenses for governmental instrumentalities that will be borne by taxpaying and voting constituencies. Efforts to address car dependency are fundamental to achieving healthy cities, but complementary approaches are also needed to drive the impetus for transitions to healthy and sustainable urban environments.

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) are a promising approach to address these challenges since urban greenery is known to be beneficial to both human and environmental health (Hunter et al., 2023). However, implementation of NbS is still “limited to isolated demonstration projects, and without attention to long-term management and maintenance” (Hölscher et al., 2023). There are structural barriers, such as the vested interests of existing systems, that prevent NbS from being integrated into core urban development practices (Dorst et al., 2022). A concerted effort between research, advocacy, and government sectors is essential to overcome the barriers and to enable transitions to be widely adopted and implemented.

Public health efforts to reduce smoking in Australia provide a prime example of large-scale societal transitions. The proportion of regular smokers declined from 35% in 1980 to 13% in 2019 (Greenhalgh et al., 2023). Tobacco control initiatives produced a nationwide shift not only in smoking behaviour but also in people’s attitudes toward it (Borland et al., 1990). The efforts were successful due to coordinated action between researchers, advocates, and government officials. Namely, researchers produced a robust evidence base, which advocacy groups disseminated to relevant stakeholders, and policymakers implemented evidence-based approaches in collaboration with advocates.

Policies and regulatory initiatives that radically changed the social and environmental contexts of cigarette smoking included tax increases, advertising bans, plain packaging, the introduction of smoke-free work environments, and the ubiquitous availability of quit-smoking services, all supported by and advocated for with compelling research evidence.

These changes were in some dimensions incremental but also included a striking instance of successful litigation followed by strong regulation to address the health impacts of passive smoking in the workplace and other settings (Chapman et al., 1990; Greenhalgh et al., 2023). It is now the social norm not to smoke in public places in Australia.

Such strategies have the potential to be applied to NbS. Researchers must generate scientifically strong and policy-relevant evidence on urban nature and its impacts on human health and environmental sustainability. Such evidence must be translated into forms that are readily understood and accepted by the public and appealing to decision-makers and regulatory bodies. In the case of tobacco control in Australia, the Cancer Council and Heart Foundation were key knowledge brokers who played a critical role in pushing the anti-smoking agenda by supporting politicians and policymakers to make wide-reaching evidence-based decisions, often in the face of well-funded pushback by pro-tobacco lobby groups and their front organisations (Chapman and Wakefield, 2001).

NbS also require powerful advocacy groups that can bring researchers, policymakers, and other stakeholders (e.g., community groups, environmental organisations, media) together with a view to facilitate coordinated action to underpin the pursuit of new (and in some of their strongest dimensions potentially contentious) NbS approaches.

References

Borland, R., Owen, N., Hill, D., Chapman, S. (1990). Changes in acceptance of workplace smoking bans following their implementation: A prospective study. Preventive Medicine, 19(3), 314-22.

Chapman, S., Borland, R., Hill, D., Owen, N., Woodward, S. (1990). Why the tobacco industry fears the passive smoking issue. International Journal of Health Services, 20(3), 417-27.

Chapman, S., Wakefield, M. (2001). Tobacco control advocacy in Australia: Reflections on 30 years of progress. Health Education & Behavior, 28(3), 274-89.

Dorst, H., van der Jagt, A., Toxopeus, H., Tozer, L., Raven, R., Runhaar, H. (2022). What’s behind the barriers? Uncovering structural conditions working against urban nature-based solutions. Landscape & Urban Planning, 220, 104335.

Giles-Corti, B., Vernez-Moudon, A., Reis, R., Turrell, G., Dannenberg, A.L., Badland, H., . . Owen, N. (2016). City planning and population health: A global challenge. The Lancet, 388(10062), 2912-24.

Greenhalgh, E.M., Scollo, M.M., Winstanley, M.H. (2023). Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Cancer Council Victoria. https://www.TobaccoInAustralia.org.au

Hölscher, K., Frantzeskaki, N., Collier, M.J., Connop, S., Kooijman, E.D., Lodder, M., . . . Vos, P. (2023). Strategies for mainstreaming nature-based solutions in urban governance capacities in ten European cities. Urban Sustainability, 3(1), 54.

Hunter, R.F., Nieuwenhuijsen, M., Fabian, C., Murphy, N., O’Hara, K., Rappe, E., . . . Kahlmeier, S. (2023). Advancing urban green and blue space contributions to public health. The Lancet Public Health, 8(9), e735-42.

Sisson, P. (2022). How the pandemic supercharged sprawl. Bloomberg CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-01-05/a-supernova-of-suburban-sprawl-fueled-by-covid

World Health Organization (2023). Noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

Ibrahim Wallee

about the writer

Ibrahim Wallee

Ibrahim Wallee; is a development communicator, peacebuilding specialist, and environmental activist. He is the Executive Director of Center for Sustainable Livelihood and Development (CENSLiD), based in Accra, Ghana. He is a Co-Curator for Africa and Middle East Regions for The Nature of Cities Festivals.

The lack of clarity with the term mainstreaming in the context of NbS stifles initiatives that focus on sustainable city planning and green technology appropriation.

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) have been keenly debated over the years as a concept with great potential to serve as a cost-effective means for nature to aid humanity in curbing climate change, biodiversity loss, and other rapidly escalating environmental problems (Ghosh, 2023). NbS and climate change are interdependently linked, and efforts at practically treating these concepts independently, irrespective of their conceptual nuances, are counterproductive because they reinforce each other. Unsurprisingly, commitments towards mainstreaming NbS have yet to gain the recognition they deserve to engender public confidence and broad acceptance. That will lead to a universal commitment to embracing NbS as a bridge for the gap between urban functionality and human survival in the global community.

Mainstreaming NbS into city and national policy planning for practical environmental project implementations at the community and national levels is a challenge due in part to the ambiguity of the definition of the concept of mainstreaming as it is conflated with other related change processes and concepts (Frantzeskaki et al., 2023). This situation undermines the planning and implementation of urban design projects and initiatives that promote resilience-building and environmental sustainability efforts, especially in the global south. The lack of clarity with the term mainstreaming in the context of NbS stifles initiatives that focus on sustainable city planning and green technology appropriation. It further fuels the scepticism about the effectiveness of NbS as a sustainable city development solution.

Indeed, there is a global swell of scepticism about the potential for misuse and abuse of NbS, with critics describing it as “a green-washing mechanism by businesses to offset their ongoing carbon emissions without curbing them” and as “a market mechanism to commodify and put a price tag on nature (Ghosh, 2023)”. These scepticisms militate against the general desire to mainstream and promote NbS as a default practice to address environmental crises.

It is a relief that part of the definitional problem was settled at the Fifth Session of the United Nations Environmental Assembly (UNEA5) in March 2022, where the United Nations (UN), through its environmental agency and global partners came up with a multilaterally accepted definition of nature-based solutions (NbS) as: “actions to protect, conserve, restore, sustainably use and manage natural or modified terrestrial, freshwater, coastal and marine ecosystems, which address social, economic and environmental challenges effectively and adaptively, while simultaneously providing human well-being, ecosystem services and resilience and biodiversity benefits” (UNEA, 2022).

The universal acceptance of this definition contributes towards mainstreaming NbS as a preferred eco-friendly and resilience-building climate change mitigation and adaptation strategy at the community and national levels. NbS actions are underpinned by benefits that flow from healthy ecosystems and target significant environmental challenges like climate change, disaster risk reduction, food security, water security, and health. These are critical for the achievement of the sustainable development goals. It makes sense to strive towards promoting its acceptance by a significant constituent of the voice of reason within the public sphere through effective citizen engagements.

However, the term mainstreaming in the context of NbS needs to be clarified. It begs for further conceptual clarifications from similar actions and concepts and remains the pathway to promoting global acceptance of NbS interventions. Recognizing the need for clarity as a cause for potential misdirection of planning and implementation of NbS interventions, as posited by (Frantzeskaki et al., 2023), is the first step in remedying the situation. Besides, NbS mainstreaming is affected by low climate literacy in sprawling slums and informal settlements within the urban landscape. This trend perpetuates hierarchies in urban communities and stifles efforts at building an inclusive society. It builds up the pressure of civil unrest based on divergent views and preferences for the acceptance and prioritization of green space development as an effective NbS intervention for sustainable city development and eco-friendly environmental sustainability.

The solution to the above-enumerated challenges to mainstreaming NbS lies in enhanced citizen participation to promote transparency, break down socially constructed hierarchies, demystify the complexities of NbS interventions through climate literacy engagements, and further recognize local knowledge as a capacity for inclusive development and resilient systems-building. It further promotes inclusive development and convergence of views and aspirations for green space city development landscapes for sustainability and resilience-building through NbS initiatives.

References:

Frantzeskaki, N., Adams, C., & Moglia, M. (2023). Mainstreaming nature-based solutions in cities: A systematic literature review and a proposal for facilitating urban transitions. Land Use Policy, 130(106661), 1-14.

Frantzeskaki, N., Tsatsou, A., Pergar, P., Malamis, S., & Atanasova, N. (2023). Planning nature-based solutions for water management and circularity in Ljubljana, Slovenia: Examining how urban practitioners navigate barriers and perceive institutional readiness. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 89(128090), 1-11.

Gaspers, A., Oftebro, T., & Cowan, E. (2022). Including the Oft-Forgotten: The Necessity of Including Women and Indigenous Peoples in Nature-Based Solution Research. Frontiers in Climate, 4(831430), 1-6.

Ghosh, S. (2023, November 17). Biodiversity, human rights safeguards crucial to nature-based solutions: critics. MONGABAY: News & Inspiration from Nature’s Frontline. Retrieved from https://news.mongabay.com/2023/01/biodiversity-human-rights-safeguards-crucial-to-nature-based-solutions-critics/#:~:text=NbS%20is%20controversial%2C%20they%20note,to%20help%20meet%20profit%20objectives.

UN. (2022). Resolution adopted by the United Nations Environment Assembly on 2 March 2022: Nature-based solutions for supporting sustainable development. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Retrieved November 17, 2023

Timon McPhearson, Nadja Kabisch, and Niki Frantzeskaki

about the writer

Timon McPhearson

Dr. Timon McPhearson works with designers, planners, and local government to foster sustainable, resilient and just cities. He is Associate Professor of Urban Ecology and Director of the Urban Systems Lab at The New School and Research Fellow at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies and Stockholm Resilience Centre.

about the writer

Nadja Kabisch

Nadja Kabisch holds a PhD in Geography. Her special interest is on human-environment interactions in cities taking co-benefits from nature-based solutions implementation for human health and social justice into account.

about the writer

Niki Frantzeskaki

Niki Frantzeskaki is a Chair Professor in Regional and Metropolitan Governance and Planning at Utrecht University the Netherlands. Her research is centered on the planning and governance of urban nature, urban biodiversity and climate adaptation in cities, focusing on novel approaches such as experimentation, co-creation and collaborative governance.

Nature-based solutions have the potential to be expanded in urban development, but only if coupled with biodiversity conservation, restoration, and protection programs as a key part of building more livable and resilient cities.

Effective nature-based solutions won’t just happen. Seven insights to move the NbS agenda forward

Our vision for cities in the future is ambitious ― a just, equitable, resilient, and sustainable landscape of virtuous relations among people, nature, and infrastructure ― and not one where nature and its benefits in cities are sporadically located or only available to a subset of population groups. This vision requires rethinking, retrofitting, and redefining cities (and their connected regions) as social-ecological-technological systems that have at their core a network of nature-based solutions. These networked NbS must be implemented and maintained, operate at city scale, connect, restore, and reinforce social-ecological flows, and provide multiple ecosystem services and co-benefits for health and wellbeing that are deeply inclusive in ways that improve and foster equity and justice.

Nature-based solutions have the potential to be expanded in urban development, but only if coupled with biodiversity conservation, restoration, and protection programs as a key part of building more livable and resilient cities. In our recent open-access edited book, Nature-based Solutions for Cities, with contributions from over 60 authors, we provide a critical starting point for developing and implementing a livable global urban vision that puts nature and people at the center of how we re-imagine, retrofit, build and redesign cities.

The key insights and next steps for urban nature-based solutions drawn from findings across all the book chapters are presented below:

Insight 1: Put nature-based solutions first in adaptation to climate change in cities

Nature-based solutions are affordable and effective in delivering protection from extreme weather events. As such nature-based solutions are “safe-to-fail” infrastructures in design and management. This is the case because nature-based solutions are more flexible in responding to shifting risk profiles or environmental changes and in accepting changes to system design and management than traditional gray infrastructure.

Insight 2: Make equity and justice central in design, planning, management, and governance of nature-based solutions in cities

From ideation to maintenance of nature-based solutions, all phases must put equity and justice at the center of, and as necessary conditions for, efficacy. This goal can be safeguarded through careful consideration and design of how participation is organized, who is represented, and how representation overall is facilitated, as well as ensuring accessibility and openness in processes and attention to distributional aspects of co-benefits or disservices of nature-based solutions.

Insight 3: Ensure biodiversity is a priority in urban planning for nature-based solutions.

Biodiversity aspects such as species richness or traits that are well studied and manageable, should be part of a NBS selection process by practitioners. Often, local knowledge provides important expertise to support species selection and maintenance decisions for resilient and sustainable long-term nature-based solutions.

Insight 4: Employ and design nature-based solutions to improve human health in cities.

Nature-based solutions are an important contribution to keeping urban residents mentally healthy, and to help them adapt to and mitigate a potentially stressful life in the urban landscape. Thus, extensive urban planning and decision-making efforts are needed to bring nature into the city and to increase nature quantitatively but qualitatively by considering the needs of a diversity of user groups.

Insight 5: Realize nature-based solutions in cities with inclusive urban planning, and innovative governance approaches that respond to local context dynamics.

To realize nature-based solutions in cities, urban policy, planning, and governance need to map and assess the local context while critically unpacking local dynamics to respond to the quest for justice and inclusivity for planning with nature-based solutions. NBS should be selected and developed to be adapted to current but also future climate conditions keeping in mind the local biodiversity.

Insight 6: Assess the holistic value of urban nature to make a case for nature-based solutions in cities.

Assessing the value of urban nature can support building a case (or a business case where needed) for investing in urban nature and restoring it or enhancing it with nature-based solutions. As we advance the science and practice of nature-based solutions, a holistic assessment of their value that is contextually informed or nuanced is the way forward. We must ask: Nature for whom? Who and how is the value of urban nature recognized and appreciated?

Insight 7: Bring art into nature-based solutions and position art as a nature-based solutions in cities

Artists can express through creative processes the emotions and relations or loss of relations with urban nature but also showcase new relations with it. Ecological art that addresses environmental issues or is situated in urban green spaces can play a crucial role in advocating for and implementing nature-based solutions. Innovating the practice of nature-based solutions should make artists more central to nature-based solutions design, planning, and implementation.

David Simon

about the writer

David Simon

David Simon is Professor of Development Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London and until December 2019 was also Director of Mistra Urban Futures, an international research centre on sustainable cities based at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Public awareness and understanding of the concept in different countries and contexts will largely depend on finding locally appropriate terms to substitute for the bland and abstract umbrella label of “Nature-based Solutions”, with illustrative examples.

The timing of this Roundtable is perfect in terms of being able to address both questions simultaneously. Public awareness and understanding of the concept in different countries and contexts will largely depend on finding locally appropriate terms to substitute for the bland and abstract umbrella label of ‘nature-based solutions’, with illustrative examples. I find this helpful even in my university teaching, although the nature of my courses means that I can and do use illustrated examples from around the world.

One of my current favourites is the highly successful rehabilitation of the Cheonggyecheon Stream running through a densely populated and congested part of central Seoul, Republic of Korea. As a result of progressive encroachment and deterioration through waste dumping and contaminated run-off, it was covered over in the 1970s, with a double-decker highway constructed above it to ease traffic congestion. This, in turn, contributed to air pollution in the resulting ‘urban canyon’ created by the tall buildings lining both sides and further declines in the neighbourhood. Proposals to demolish the highway and redevelop the stream proved highly controversial but provided a popular election platform for a mayoral candidate and the project was subsequently undertaken, with the rehabilitated and decontaminated waterway being opened in 2005. Despite some early criticism, it has been improved and both terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity enhanced over the years. Today it is a well-used and attractive recreational walkway, within the constraints of the sunken nature of the site (Figure 1). Historico-culturally referenced tile murals decorate the sides (see Choi 2010; Simon 2024: 68-71).

My other example is collaborative work underway at present with Runnymede Borough Council (RBC), the local district within which Royal Holloway (RHUL) lies and which is the local planning authority within the county of Surrey’s two-tier local government structure. In line with central government policies consistent with its international commitments to net zero and biodiversity conservation, all local councils must develop a green-blue infrastructure (GBI) strategy, while new development schemes and projects have to demonstrate biodiversity net gain. RBC is currently holding an early stakeholder consultation on its high-level outline GBI strategy, prior to further development work, leading to full public consultation on the entire strategy, any required revisions, and then adoption.

Since RHUL is one of the largest institutions and private landholders within Runnymede, and I have led the formation of a strategic partnership between RHUL and RBC, I drew together a small group of appropriate specialists of both academic and professional service colleagues to assess and feedback on the draft. Biodiversity net gain and other current priorities are integrated into the document. An additional important innovation is that the policy seeks to ensure overall voluntary co-ordination and integration of GBI across both public and private waterways, wetlands, and land within Runnymede. This should maximise wildlife corridors and habitat restoration, while promoting ‘soft’ approaches to sustainability and flood resilience over ‘hard’ engineering designs that tend to displace floods.

Since another strand of the strategic partnership involves helping RBC set up a deliberative democratic ‘citizens’ panel’ next calendar year, this will provide an ideal forum for engaging different stakeholders and communities in seeking to bridge the classic divides between the Council and these residents and landholders, helping to forge more of a shared vision and understanding of biodiversity enhancement and GBI as part of sustainability and net zero transitions, as well as resilience in relation to existing local flood risk on the River Thames and some of its local tributaries.

References:

Cho, M-R (2010) The politics of urban nature restoration: The case of Cheonggyecheon restoration in Seoul, Korea. International Development Planning Review 32(2): 145-165. Https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2010.05

Simon, D. (2024) Sustainable Human Settlements within the Global Urban Agenda; Formulating and implementing SDG 11. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing, xiv+146pp. https://www.agendapub.com/page/detail/sustainable-human-settlements-within-the-global-urban-agenda/?k=9781788214957

Stuart Connop

about the writer

Stuart Connop

Dr Stuart Connop is an Associate Professor at the University of East London’s Sustainability Research Institute specialising in biomimicry/ecomimicry in urban green infrastructure design.

Local mainstreaming is critical if we are to reach a tipping point whereby NBS becomes so embedded in our local urban landscapes that people stop noticing it as something risky and unusual, and instead, it becomes something expected, and desired, in urban design.

Having worked on a number of nature-based solutions research and innovations projects, including one specifically targeting the goal to ‘mainstream NbS’, I have spent many hours contemplating the question of: what do we mean by mainstreaming NbS? For me, NbS will be mainstreamed when we reach a point whereby ecological restoration and protection become the de facto starting point for any policy and planning decisions. In other words, mirroring how carbon impact is becoming a foundational component of cross-sectoral policy and practice decisions (no longer just within the environment sector), mainstreaming NbS is the situation whereby nature-positive outcomes are embedded as standard. This would mean:

- ensuring no net-harm to nature is the absolute red line for policy and planning;

- that nature stewardship and restoration is considered a key target for policy, planning, finance, and business strategic development decisions;

AND

- that the “values” that nature provides (ecosystem services) are considered as a first point of call for solutions across the spectrum of societal challenges that underpin policy and practice objectives.

Only by reaching such a situation are we going to be able to tip the scale of global biodiversity declines towards one whereby we halt global loss and start restoring nature to a state where it underpins a healthy & stable global ecosystem able to support itself, including humans as part of that ecosystem.

In terms of how to get there, that is a huge question, a question I’ve found challenging to answer in several of my past publications, let alone in a short one like this. However, here is my attempt at a short answer: it requires different actions across different scales. At the largest scale, it requires reconnecting our communities with nature and supporting them in understanding the key role that nature plays in keeping planetary systems balanced and us all healthy and happy. That starts with the early years of education and development but needs to continue through secondary and higher education, and even into life-long learning. Human rights, equality, inclusivity, and diversity are fundamental components of mandatory life-long learning approaches in the workplace, why not the rights of nature too, and its value in supporting every aspect of our lives? And why stop there? NBS mainstreaming also needs to be embedded in corporate social responsibility. If an individual is struggling with the cost of living, they can’t be expected to make decisions based on what is good for the planet, or good for wildlife, they need to be making decisions that are good for themselves and their families. Responsibility therefore needs to be shifted from the consumer to the producer: the businesses, governments, and financial markets. Only by doing this can you ensure that all decisions, whether driven by desperation or decadence, are fundamentally linked to the protection of nature.

Whilst the global NbS community continues to push for this incremental large-scale change, there is also a need to consider the small-scale incremental change that unlocks local mainstreaming. Local mainstreaming is critical if we are to reach a tipping point whereby NBS becomes so embedded in our local urban landscapes that people stop noticing it as something risky and unusual, and instead, it becomes something expected, and desired, in urban design. There have been many studies that have explored the barriers and drivers to unlocking NbS scaling, with many identifying similar governance, policy, and financial levers. However, in addition to these usual suspect barriers, there is also a need to listen to local practitioners to understand their needs for delivering NBS mainstreaming.

A recent study I was involved in collaborated with practitioners to explore barriers to the roll out of small-scale Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) in London and the River Thames catchment. Whilst some of the barriers identified represented the usual suspects (access to funds, cost to maintain, and ownership, issues), the study also identified some surprising patterns: Insurmountable barriers for one individual were often not perceived as a barrier at all by others. Overall, the research found three key themes in relation to barriers perceived by participants: people-related elements, limiting practicalities, and informational factors. However, by far the simplest solution to unlocking many of the barriers to locally mainstreaming SuDS could be solved by becoming better at communicating and sharing knowledge and innovative practice. A simple example of this? Why do we give awards for the prettiest SuDS and not the ones that share the most information on how they were delivered? Or the ones that drive the most sector-wide exchange? And, on the subject of being better at communicating to unlock mainstreaming, I must get back to getting that study written up!

Zbigniew Grabowski

about the writer

Zbigniew Grabowski

Dr. Zbigniew J. Grabowski (Z or Zbig for short) is an Extension Educator in Water Quality at UConn’s Center for Land-use Education and Research (CLEAR). Z’s primary work is to support just transformations of land systems. His work focuses on green infrastructure, just transitions, and systems approaches to address intersecting social and environmental challenges.

We must remember that the current push for NbS is inherently restorative ― cities and the infrastructures they rely on all occupy (often colonized!) ecosystems and have developed in ways that required and reinforced social injustices and inequalities.

Mainstreaming NbS vs Just Transformations: A perspective from a water person

What does it mean to mainstream? As a kayaker and canoer, mainstreaming implies riding the deepest and dominant current ― the one following what hydrologists call the ‘thalweg’ ― a German word translating to the ‘valley way’ where the current is shaped by the landscape and in turn, shapes the river bed. Sitting in an eddy, amidst the chaos of a big rapid, you can observe the mainstream and study its habits. When it’s time to go, you know you’ve hit the mainstream when you cross the turbulence of the eddy line, feel that bump under your boat, and rapidly accelerate down river. Mainstreaming then, is finding the path of maximum flow, or the path of least resistance defined by how the structures surrounding the flow ― be they rocks, institutions, or built infrastructures ― and the force which is flowing itself ― be it water, ideas, or money. As we move towards mainstreaming NbS, I urge my fellow researchers and practitioners to keep this duality in mind: we are both shaping and being shaped by social currents and structures.

We have a tremendous and historical opportunity to green cities, accelerate circular bio-economies, and engage in just transition work with NbS. And yet we must remember that the current push for NbS is inherently restorative ― cities and the infrastructures they rely on all occupy (often colonized!) ecosystems and have developed in ways that required and reinforced social injustices and inequalities. Restoring ecological systems in cities and transforming technological infrastructures causing harm to human and ecological health are vital and necessary tasks. And yet I deeply question if these tasks can be accomplished through the current structures that have shaped our cities. In over 17 years of experience working on different dimensions of sustainability transitions, urban greening, and ecological restoration and conservation, I have come to believe that the dominant institutions cannot be trusted to enable, steward, or catalyze the necessary transformations, primarily because of their intractable desire to control the flows of ideas and resources. In short, our current landscape of institutionalized inequity is shaping the mainstreaming of NbS, and it will take seismic changes to enable the just transition.

The primary obstacle to just transformations in cities, infrastructures, and landscapes is overcoming the inertia in the political and financial structures directing flows of ideas, material wealth, and labor. This inertia also permeates the academic establishment, which has an uneasy relationship with change. On the one hand, universities are epicenters of the critical thinking and innovation that emerge from concentrations of inquiring minds. On the other, they are the bastions of the prestige economy, the largest gatekeepers of credibility. Funding for research has become progressively more inequitable in the USA, UK, and elsewhere, with funding and collaborations driven by elite institutions and established networks.

To be effective in pushing these larger systemic transformations, the research and practice communities must individually and collectively address our own biases and personality issues that pervade the social hierarchies that delineate which approaches are acceptable and which ones are not. Elsewhere co-authors and I have called for convivial pluralism in developing the NbS agenda, and to their credit, networks like NATURA attempt a broadly inclusive approach but mirror the larger inequities in NbS research and practice (e.g., limited representation from the Global South and minoritized peoples).

Like water flowing down river, the barriers and boundaries, the eddy lines if you will, can be subtle and deep, and we would be wise to keep an open heart and an open mind to identifying and dismantling them before we rush downstream with the dominant flow. The massive inflow of federal funding through ARPA and the IRA in the US, and from the EU for the Green New Deal and circular bioeconomy all have stated agendas to support equitable transformations of these systems. The mainstream is being pointed at challenges of sustainability and resilience that have been created by the structures still directing the flow.

In a river, change can be subtle, slow, and somewhat predictable ― when the Marmot Dam was removed as part of the Bull Run Decommissioning on the Sandy River outside of Portland Oregon, the movement of sediment downstream behaved in accordance with well-understood physical principles, for the most part. This was despite heavy rains during the initial removal accelerating the initial clearance of the former reservoir, and a somewhat unexpected backup at the river’s mouth compounded by static infrastructures including a highway bridge (I-84), rail line, gas pipelines, and a heavily modified floodplain. In contrast, across the Columbia River gorge, the removal of the Condit dam on the White Salmon proceeded with a violent explosion of sediment which temporarily blocked river access for the Native community of fishers downstream and may have removed vital cold water habitat adjacent to the Columbia mainstem, also because of a state highway bridge blocking the river’s mouth. While these types of large dam removals are heralded as major successes for ecological restoration, they can still overshadow the persistent calls for Indigenous environmental justice finally being acknowledged by the US government.

All over the world, we see technological infrastructures and political institutions limiting the effectiveness of ecological restoration, compounding internal issues in the restoration community of overreliance on technical expertise rather than community knowledge exacerbated by funding territorialism. In our rush to accelerate NbS, we must take care to not only ‘include’ Indigenous, minoritized, and marginalized populations, as well as minority viewpoints within the field, but to support their resurgent leadership towards a just world characterized by flourishing biocultural relations. This task runs deep, and yet without it, the mainstream will only perpetuate the injustices we say we are trying to solve.

Israa Mahmoud

about the writer

Israa Mahmoud

Israa Mahmoud is a polyglot Architect and Urban Planner. She is an Assistant professor in urban and regional planning at Urban Simulation Lab, Department of Architecture and Urban Studies of Politecnico di Milano. She is lately involved in the National Biodiversity Future Center (NBFC) as a researcher on co-creation and co-governance themes related to urban biodiversity in living labs.

It will take a bit more than the EU Nature Restoration Law to be passed to make sure that cities prioritize a Nature-based Solutions approach for nature-human approaches.

Mainstreaming NbS for a shared governance of urban biodiversity, intertwined concepts

In the latest academic debate, the shift from nature-based solutions to a more generic approach on urban biodiversity has emerged after the definition of UNEA-res 5.5. on NBS that encourages a comprehensive approach to embrace NbS versatility. Meanwhile, the missing part of the puzzle is the technical, financial, governance, and spatial possibility of rolling out NbS in different contexts as a “Passepartout” key concept that fits all climate, social, and environmental challenges.

Indeed, several research articles criticize the “right message” to convey on NbS in a mainstreaming policy era in which the use of NBS is considered a magical solution to solve both climate change and urban biodiversity challenges (Seddon et al., 2021; Xie & Bulkeley, 2020). Nonetheless, the reframing of the current governance mechanisms towards urban biodiversity seems an intertwined concept with the possibility to mainstream NBS across scales and levels of implementation in cities which is challenging on so many levels (Kowarik, 2023).

Even with the adoption of novel concepts in urban planning such as co-creation processes (Cortinovis et al., 2022; Łaszkiewicz et al., 2023; I. H. Mahmoud et al., 2021; I. Mahmoud & Morello, 2021) the challenge remains on the level of readiness in which the citizens are ready to be engaged within the process. Also, another challenge is the inclusivity level at which these processes are initiated and executed. The NBS mainstreaming processes require technical and political support from the local municipality authorities which they currently do not possess in place coherently (Hölscher et al., 2023). Another major challenge is still a comprehensive framework that assesses the NBS co-benefits to convince decision-makers to adopt NBS as the longer-term solutions taking into account not just the environmental assessment but also the social return of investment.

What will it take to be there? In my opinion, it would take a bit more than the EU Nature Restoration Law to be passed to make sure that cities prioritize a nature-based solutions approach for nature-human approaches. Our relationship with nature is valuable and unless there is an evident prioritization across many sectors, we might not get there, yet!

References:

Cortinovis, C., Olsson, P., Boke-Olén, N., & Hedlund, K. (2022). Scaling up nature-based solutions for climate-change adaptation: Potential and benefits in three European cities. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, 67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127450

Hölscher, K., Frantzeskaki, N., Collier, M. J., Connop, S., Kooijman, E. D., Lodder, M., McQuaid, S., Vandergert, P., Xidous, D., Bešlagić, L., Dick, G., Dumitru, A., Dziubała, A., Fletcher, I., Adank, C. G.-E., Vázquez, M. G., Madajczyk, N., Malekkidou, E., Mavroudi, M., … Vos, P. (2023). Strategies for mainstreaming nature-based solutions in urban governance capacities in ten European cities. Npj Urban Sustainability, 3(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-023-00134-9

Kowarik, I. (2023). Urban biodiversity, ecosystems and the city. Insights from 50 years of the Berlin School of urban ecology. In Landscape and Urban Planning (Vol. 240). Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104877

Łaszkiewicz, E., Kronenberg, J., Mohamed, A. A., Roitsch, D., & De Vreese, R. (2023). Who does not use urban green spaces and why? Insights from a comparative study of thirty-three European countries. Landscape and Urban Planning, 239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104866

Mahmoud, I. H., Morello, E., Ludlow, D., & Salvia, G. (2021). Co-creation Pathways to Inform Shared Governance of Urban Living Labs in Practice: Lessons From Three European Projects. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 3(August), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.690458

Mahmoud, I., & Morello, E. (2021). Co-creation Pathway for Urban Nature-Based Solutions: Testing a Shared-Governance Approach in Three Cities and Nine Action Labs. In A. Bisello et al. (Ed.), Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions (pp. 259–276). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57764-3

Seddon, N., Smith, A., Smith, P., Key, I., Chausson, A., Girardin, C., House, J., Srivastava, S., & Turner, B. (2021). Getting the message right on nature‐based solutions to climate change. Global Change Biology, 27(8), 1518–1546. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15513

Xie, L., & Bulkeley, H. (2020). Nature-based solutions for urban biodiversity governance. Environmental Science and Policy, 110(December 2019), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2020.04.002

James Bonner and Tam Dean Burn

about the writer

James Bonner

Dr. James Bonner is a Research Associate at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland. His interests and background are in a range of interdisciplinary research issues and themes including water, trees, place and mobility. He is particularly interested in the relationships between people and society to the places and spaces they inhabit and encounter.

about the writer

Tam Dean Burn

Tam Dean Burn has been a professional actor across platforms for over forty years and a performer, particularly of musical varieties, for even longer. He is also a very active activist in local, national and international campaigns. Most recently he has led a successful campaign to press Glasgow City Council to drop the plan for entry charges to the iconic 150 year old Kibble Palace in the city’s Botanical Gardens.

A conversation… What are NbS?

How do we get to that more reflective appreciation of nature that we are part of, including the language we use? Perhaps, rather than seeing Nature-based “Solutions” in terms of an “answer to a problem” can we think of “solution” in its more watery terms?

It is looking at how we ARE nature, and finding the solutions in nature to some of the challenges we face. Trees are the thing that connects us two in the ‘Every Tree Tells a Story’ project, but also all of us. They are maybe our closest allies in nature. If we develop our relationship with them, and then other elements they interact with ― like the mycorrhizas ― fungi they are connected to, and the water, and ultimately the wider ecosystem ― then we facilitate that conversation and thought process: recognising that we are part of, and interconnected within nature. Connections we can make in the city, as much as anywhere else.

One way to do this could be changing to think and operate around the lunar cycle, rather than the solar cycle. A consequence of climate change and warming temperatures will mean that days are going to become more difficult to operate within, so might we need to shift more activity to the night? How can we become more in tune with nocturnal nature? And can we build a flourishing nighttime economy around this, powered by solar panels from our days?

Consider that the monthly cycle of the moon means that there are periods when it is darker at night, and others in which is lighter ― the waxing and waning from dark to full moon. We recognise the power of the latter. How can we also align with the dark moon? The solarising of the moon, by giving the sun its symbolic ritualistic ruling over us has been a process over fairly recent time, roughly the last 3000 years. But there are other, older ways of thinking that recognise the value of lunar cycles as a way to think of time and our own being.

By thinking in more lunar cyclical ways can we rethink ideas of death and rebirth, rediscovering ways of seeing life and death as interconnected. Compared to trees, for example, who experience a seasonal cycle of life and death, it is in the moments of ‘death’ (in autumn) that they regenerate to become new life.

What do we mean by mainstreaming NbS and what will it take to get there?

The very word “mainstreaming” struck us as having water connections― and water, aside from trees, is a thing that also connects us. (Tam’s surname “Burn” is a Scottish term for a small stream ― so both fire and water elements ― and in name terms “by the river”. James’s research background considers the social and cultural values of water. We are both watery Zodiac signs― Cancer and Pisces!).

Is a way of mainstreaming NbS to rediscover old myths about nature and our interconnection to it, or recognising words, terms, and things like the animalistic roots of our alphabet as being part of that? Is it also something to do with ensuring the NbS process is not top-down, but rather from the bottom up, and potentially female-led, recognising the links between the feminine and the lunar― the very embodiment of such a cycle?…

Thinking of water reconnects the link to the lunar― the moon having control over the ebb and flow of the tides. How do we get to that more reflective appreciation of nature that we are part of, including the language we use? Perhaps, rather than seeing Nature-based “Solutions” in terms of an “answer to a problem” can we think of “solution” in its more watery terms? Where a solution is a mixture of different substances, and water is the solvent in the process. By thinking in terms of water, do we open up multiplicity and plurality?

Cecilia Herzog

about the writer

Cecilia Herzog

Cecilia Polacow Herzog is an urban landscape planner, retired professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. She is an activist, being one of the pioneers to advocate to apply science into real urban planning, projects, and interventions to increase biodiversity and ecosystem services in Brazilian cities.

Mainstreaming requires that diverse actions and activities converge to promote interdisciplinary knowledge and common ground to a wide range of stakeholders and agents: public and private, individuals and organizations (formal and informal).

The Cartesian/Mechanistic vision of urbanization that intended to control natural processes and flows has been dominant, mainly since the mid-XIX Century. The current globalized neoliberal economic system has accelerated the exploitation of natural and human resources mainly in the Global South, causing heavy impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity. Sprawling urbanization is an outcome of this predatory paradigm, causing the eradication of natural and agricultural areas, with landscape transformation leading cities to extreme climatic vulnerability.

This year the critical acceleration of the climate impacts, and the evident changes in the Earth’s system functioning, have led to the speed of the implementation of responses to mitigate the impacts of human activities in many spheres. In this context, mainstreaming nature-based solutions is urgently needed to shift to a new regenerative paradigm.

I have been researching, teaching, and advocating for the adoption of NbS in urban areas for the last 15 years. In my experience, which I consider quite successful, mainstreaming requires that diverse actions and activities converge to promote interdisciplinary knowledge and common ground to a wide range of stakeholders and agents: public and private, individuals and organizations (formal and informal). In this manner, people work together with mutual and complementary interests to regenerate the landscape, urban or not.

I have been in close contact with individuals and grassroots movements that are transforming the pervious and sterile landscapes into urban oasis, with the introduction of pocket forests, biodiverse rain gardens, food gardens, and also, the restoration of urban springs and creeks in parks and in small sites and organizing collective tree and food plantings in dense urbanized areas, besides other communal activities. After more than a decade of intense mobilizations and actions, they are resisting to further eliminate nature-urban assets with judicial actions, halting new constructions in ecologically valuable sites. Furthermore, they are promoting policy changes. The media finally is giving place to those committed, courageous, and noisy urban heroes.

Looking from the top-down perspective, the articulation of several NGOs and academic institutions with the same goal to mainstream NbS is key. They are the ones who give technical and scientific support to city officials to develop robust plans, projects, programs, and policies. The NGOs are also important agents in pushing the mainstreaming of NbS in traditional and social media.

The role of visionary decision-makers is to be drivers of actual landscape transformations. They are the ones who have the capacity to foresee the benefits of their choices when introducing NbS in their cities to mitigate, adapt, and build resilience, as well as enhance the quality of life and well-being of their citizens.

The innovative NbS projects bring people to enjoy the “natural” places, so they can value nature close to where they live.

The fertile soil that enables all the above outcomes is education! So, mainstreaming NbS is only possible with cascading processes to develop research, active learning, and co-creating spaces of exchange of experiences and knowledge. Nature-based solutions are the way forward to face the present systemic and frightening challenges. Let’s definitely enter the new regenerative paradigm that focuses on the life of humans and non-humans, fauna and flora!

This year, climate emergency and Earth’s planetary system’s extreme stress are evident. After years of advocacy for protecting, conserving, and regenerating nature all over the world, nature-based solutions have become the bright star in multiple agendas, from ecological, to social and economic perspectives. But to really mainstream NbS there is an urgent need to have people prepared to plan, design, implement, manage, and monitor nature in and out of the cities.

In the last century, there was a belief that development and growth of the economy, where the dominant elites could and should exploit natural and human resources to achieve a better future, and then the benefits would be shared by all. This definitely didn’t happen. The externalities of this worldview are huge. We are on the brink of the Earth’s system collapse due to a misguided vision of the world as a machine, that people are like clocks, all made of separate parts that could be studied separately to understand the whole.