In the recently released book Greening in the Red Zone, I and many of my colleagues argued that people who have recently experienced surprise, shock and other perturbations (such as created by disasters and war) often demonstrate a significant interest in greening and ecological restoration activities. Those of us who work in urban settings are always interested in groups of people who express interest and support for urban greening and restoration. As wars of the last ten years or more draw to a close an important group of people who have a great deal of experience in the red zone are returning to our cities. These returning warriors may represent both active, well trained and motivated future participants in greening and restoration, and may be excellent examples themselves of the value of greening and green spaces.

3.4 million United States Veterans have a service-connected disability, and they are not all men. More than 250,000 women served in Iraq and Afghanistan, compared with 7,500 during the Vietnam War. While the rate of suicide of young male veterans is reaching epidemic proportions, young women who have served in the military face a suicide risk triple that of non-veterans. Medical and public health officials are desperately seeking more effective ways to address concerns about combat veteran reintegration. Though this issue is not purely an urban issue, it relates to urban studies in both obvious and less obvious ways, and presents an important opportunity to remind us all about the power of nature in healing.

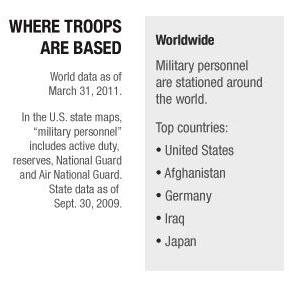

As of a couple of years ago, there were 2,266,883 people serving in the U.S. military, many of whom serve on bases in the U.S. or abroad. The majority of Active Duty members (86.5%) are stationed in the United States and U.S. territories. The next largest percentages of Active Duty members are stationed in East Asia (7.1%) and Europe (5.8%). The largest base in the US is Fort Bragg, which is home to 55,000 military and 8,000 civilian personnel. With a population of over 60,000 people, Fort Bragg is about the size of Utica, NY, a small, but distinctly urban city in the U.S. (see Note 1).

As of a couple of years ago, there were 2,266,883 people serving in the U.S. military, many of whom serve on bases in the U.S. or abroad. The majority of Active Duty members (86.5%) are stationed in the United States and U.S. territories. The next largest percentages of Active Duty members are stationed in East Asia (7.1%) and Europe (5.8%). The largest base in the US is Fort Bragg, which is home to 55,000 military and 8,000 civilian personnel. With a population of over 60,000 people, Fort Bragg is about the size of Utica, NY, a small, but distinctly urban city in the U.S. (see Note 1).

The benefits of human-nature interaction as a form of therapy are well documented. However, the value of human-nature interaction for returning combat veterans and their families and communities has been less studied. While administrators in the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs struggle to design programs to help returning combatants reintegrate into communities, programs started by veterans themselves have emerged in New York State and across the U.S. Notably, many of these programs have a focus on the healing power of interacting with nature through outdoor recreation, including hunting and fishing, and through other restoration and greening activities. Examples include Wounded Warriors in Action Foundation, Project Healing Waters, Veteran Outdoors, Veterans Conservation Corps of Chicagoland, and Growing Veterans, among many others. Testimony from program participants indicates their powerful impact on vets.

The benefits of human-nature interaction as a form of therapy are well documented. However, the value of human-nature interaction for returning combat veterans and their families and communities has been less studied. While administrators in the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs struggle to design programs to help returning combatants reintegrate into communities, programs started by veterans themselves have emerged in New York State and across the U.S. Notably, many of these programs have a focus on the healing power of interacting with nature through outdoor recreation, including hunting and fishing, and through other restoration and greening activities. Examples include Wounded Warriors in Action Foundation, Project Healing Waters, Veteran Outdoors, Veterans Conservation Corps of Chicagoland, and Growing Veterans, among many others. Testimony from program participants indicates their powerful impact on vets.

Although a number of research projects are being conducted on reintegrating veterans, a recent literature review revealed only one research project on the impact of nature programs, the results of which were inconclusive. A current study on human-nature interactions among families dealing with deployment suggests that such interactions contribute to individual and community resilience among families and communities where deployment of soldiers to combat zones creates disturbances in social-ecological systems. We know of no studies that look specifically at female returning vets and human-nature interactions. The work presented in overview fashion herein attempts to move beyond these limited studies and begins to fill some gaps in terms of exploring the importance of human-nature interactions in outdoor recreation activities among returning war veterans, male and female, including those disabled in combat, and then accounting for how these interactions relate to individual, community, and social-ecological resilience.

To begin to understand these issues, I started attending events and getting to know the main players working at Fort Drum in the area of Morale, Welfare and Recreation (MWR), the Natural Resources group, and others working in the area of “navigating the deployment cycle.” Fort Drum is an army base in upstate New York that has seen frequent deployments of large numbers of troops in the past few years.

An initial event included one held on post where women and children were able to learn how to plant vegetables in containers. Some of these containers were sent to Afghanistan so that the women’s husbands deployed there could also garden, the idea being that this “distance-gardening” would create shared experience and “common ground” between the deployed soldiers and those left home.

I also participated in and helped coordinate Earth Day festivities on Fort Drum, again, to try to get a sense of the way human-nature experiences might be similar or different among this specific community (the military community). We set up a table to attract participants with children that featured a theme of “lending a hand to the planet.” The children worked with their parents to write down one thing that they would do to “lend a hand to the planet” on a colorful cut-out of their hand and then were invited to place the hand on the larger poster of planet earth.

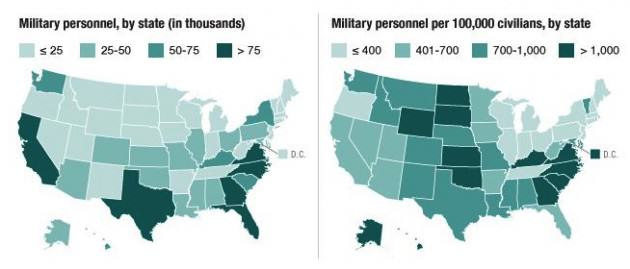

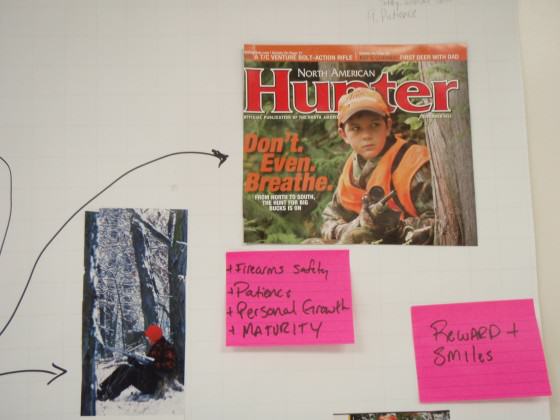

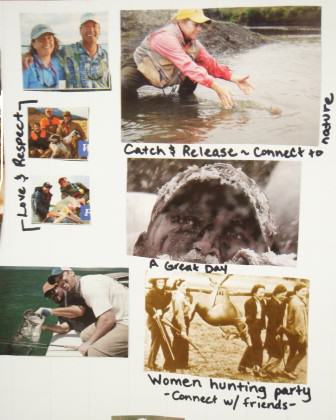

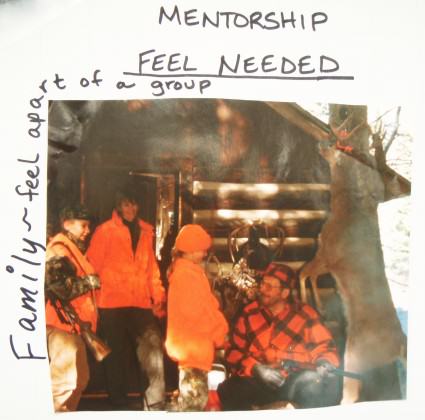

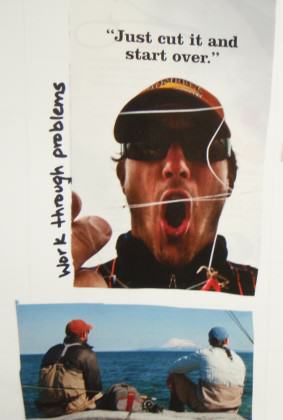

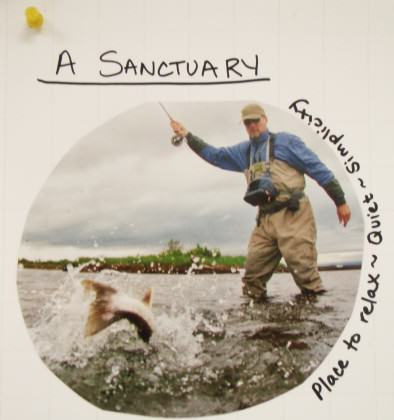

I later convened groups of veterans in the Fort Drum area to explore how outdoor recreation helped them reintegrate with their families and communities. I employed a method I have called “Collaborative ‘Cut and Paste’ Concept Mapping” (C3M) wherein participants are broken up into teams of 3-5 persons. They are then given a simple task to, in this case, map the multiple ways in which outdoor recreation is important to veteran reintegration. Participants are given no elaboration on the task and outcome. Participants are given a large supply of magazines ranging from general health magazines, hunting and fishing magazines, non-consumptive outdoor recreation magazines, gardening and hobby farming magazines, lifestyle magazines, and electronic industry magazines. They are also given scissors, glue sticks, sticky notes, a package of markers of different colors, and easel paper. Participants are then instructed to spend the first 15 minutes of group time “brainstorming” what they as a group feel are the important meanings and messages they would like to depict, and sketching a general schematic of how they will depict these meanings and messages on their final C3M map. Participants then begin a 90 minute period of interactivity to create the C3M map.

This method is useful both in terms of the final product, which is a visually interesting and conceptually intriguing collage, and in terms of the interaction opportunity to share with fellow veterans in a topic-focused, collaborative and creative endeavor. The following images are examples of the themes and linkages generated via this method. These are being used to better understand common themes and concepts for later use in content analysis of interview data.

So what have we learned and where do we go from here?

So what have we learned and where do we go from here?

Whether through working with military families on installations such as Fort Drum doing gardening activities and other traditionally “earth friendly’ activities, or working with retuning combatants — many of them wounded — in outdoor recreation with organizations such as Wounded Warriors in Action Foundation, Project Healing Waters, and many others, one common theme continues to emerge in this work: the importance of interaction with the rest of nature for veterans and their families.

Work in this area is ongoing, and data gathering and analysis is underway in multiple studies. Though conclusive statements remain in the future, the evidence thus far suggests that outdoor recreation, from gardening and tree planting to hunting and fishing are uniquely powerful and multifaceted avenues for returning combatant reintegration and healing, as is depicted in this Field & Stream video portraying some of this important work.

Soldiers returning from long and protracted wars, especially with life altering injuries, often report feelings of inadequacy and of being devalued, and of feeling that their particular skill sets and competencies are not applicable in civilian life. On the other hand, returning veterans that engage in outdoor recreation and restoration activities report significant relief from these and other feelings, sometimes for short periods of time and more often for longer periods. In these reports are suggestions that reveal an intensification and specific manifestation of Kellert’s Typology of Values of Nature.

Soldiers returning from long and protracted wars, especially with life altering injuries, often report feelings of inadequacy and of being devalued, and of feeling that their particular skill sets and competencies are not applicable in civilian life. On the other hand, returning veterans that engage in outdoor recreation and restoration activities report significant relief from these and other feelings, sometimes for short periods of time and more often for longer periods. In these reports are suggestions that reveal an intensification and specific manifestation of Kellert’s Typology of Values of Nature.

Specifically, in the case of returning veterans, the values depicted graphically by soldiers themselves as in the above images indicate the importance of rekindling camaraderie, the value of nature as solace and solitude, the potential of mission accomplishment, and the important inner work of reconnecting to and understanding the sacredness of both life and death, as represented by planting a tree, harvesting a crop, by catching and then releasing a trout, or by taking the responsibility of taking the life of an animal to provide for one’s family. These are not trivial matters, and they represent a specific manifestation of Greening in the Red Zone that may hold clues to how urban society, human society, may rediscover its ecological identity.

I conclude with the story of Chicago area based restoration ecologist Ben Haberthur, a former Marine who deeply believes that working in nature can help veterans heal their war-wounded spirits. Ben, who started the Veterans Conservation Corps of Chicagoland, was stationed in southern Iraq in 2003. Upon returning to the United States, he found that exploring coastal areas in California was a “peaceful, calming alternative to the stresses of my former military life.” He believes connecting with nature could help veterans struggling with post-traumatic stress disorder. He also said his resolve to protect and restore American ecosystems was solidified after seeing environmental devastation wrought by Saddam Hussein, including draining Iraq’s southern marshlands. The lush marshlands, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, were drained after the first Gulf War, because Hussein thought the area harbored rebels.

Haberthur obtained a $10,000 grant from TogetherGreen, which is an organization run by the National Audubon Society and Toyota, to start the Chicago chapter. He observes that military service is a place where you can readily see that your actions are having an impact and says that “once you get out of the military, people still want to have that sort of impact in their life…they want to be part of something bigger than themselves…being in nature more led to a stronger connection with nature, so it went hand in hand that I would be restoring natural environments at the same time that I was trying to bring a balance and restoration to my life.”

It is my hope that urban planners, those involved in urban ecological applied research and those involved in restoration activities will recognize and appreciate two important things; first, the great potential of the veteran community to participate in the restoration work that is increasingly an important part of what we understand to be the “nature of cities,” and second, the invaluable power of nature and the time we spend in it to heal the deepest and most destructive wounds.

Keith Tidball

Ithaca, New York

Note 1: According to the US Census Bureau, urban is defined as “all territory, population, and housing units in urbanized areas and in places of 2,500 or more persons outside urbanized areas.” See http://www.census.gov/population/censusdata/urdef.txt

About the Writer:

Keith Tidball

Tidball conducts integrated research, extension, and outreach activities in the area of ecological dimensions of human security. The overarching theme of his work is better understanding how to amplify recruitment of citizen conservationists and resulting development and proliferation of a 21st century land ethic.

Great work Dr. Tidball. I appreciate your focus and relentless effort to bring awareness to just how powerful and effective the great outdoors can be to veterans! ~Bravo Zulu!!!