To fully realise the advantages of increased urbanism, people will have to influence the decision-making process within their cities, to ensure that the value that is being created is not accentuating inequality but rather promoting inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable cities.

The sustainable development framework recognises the importance of cities for sustainable development, where Goal 11 of the Sustainable Development Goals[v] is to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable, with specific targets to be achieved by 2030:

- Target 11.1 by 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services, and upgrade slums.

- Target 11.2 by 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons

- Target 11.3 by 2030 enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacities for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries

- Target 11.4 strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage

- Target 11.5 By 2030, significantly reduce the number of deaths and the number of people affected and substantially decrease the direct economic losses relative to global gross domestic product caused by disasters, including water-related disasters, with a focus on protecting the poor and people in vulnerable situations

- Target 11.6 by 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality, municipal and other waste management

- Target 11.7 by 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, particularly for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction[vi] (SFDRR) also has goals, at the national and city level, to make cities more inclusive, safe, sustainable and resilient.

Notwithstanding the importance of the above frameworks, goals and targets within, these on their own will not effect change as their implementation remains optional, and in some instances runs against deeply engrained short term vested interests. Indeed, recent past experience in the implementation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) have shown that implementation was partial. In order to be truly holistic, with a higher chance of successful implementation, these frameworks need to account for the following challenges and opportunities:

-

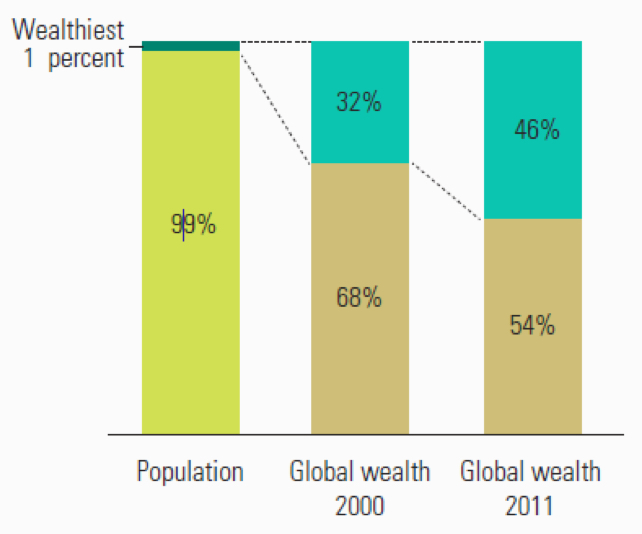

Global wealth has become far more concentrated among fewer people. Source: Human Development Report 2016, Human Development for Everyone, United Nations Development Programme. Inequality in general is increasing, where global wealth has become far more concentrated. Around 2000, the wealthiest 1 percent of the population had 32 percent of global wealth. By 2010 it was 46 percent. The share of national wealth among the super-rich (the wealthiest 0.1 percent) in the United States increased from 12 percent in 1990 to 19 percent in 2008 (before the financial crisis) and to 22 percent in 2012 (critics pointed to inequality as one of the key causes of the crisis)[vii]. Within cities, in 2010, more than 827 million people were living in slum-like conditions[viii] and nearly 40 percent of the world’s future urban expansion may occur in slums[ix]. In spite of great progress in improving slums and preventing their formation—represented by a decrease from 39 percent to 30 percent of urban population living in slums in developing countries between 2000 and 2014–absolute numbers continue to grow and the slum challenge remains a critical factor for the persistence of poverty in the world[x]. Hence upgrading slums is of paramount importance to reduce poverty in all its forms (poverty, abject poverty and chronic poverty) and dimensions (access to water and sanitation, decent and safe housing, clean and affordable energy, health, education, livelihoods, employment, etc.), thereby also addressing inequality.

- The issue of slums must also be addressed in order to reduce violent extremism, where according to the World Bank among the factors that lead people to leave the country and join radicalized groups is the lack of social and economic inclusion in their country of residence[xi]. According to the United Nations Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism[xii], there is a need to take a more comprehensive approach which encompasses not only ongoing, essential security-based counter-terrorism measures, but also systematic preventive measures which directly address the drivers of violent extremism namely: lack of socioeconomic opportunities, marginalization and discrimination, poor governance, violations of human rights and the rule of law, amongst others.

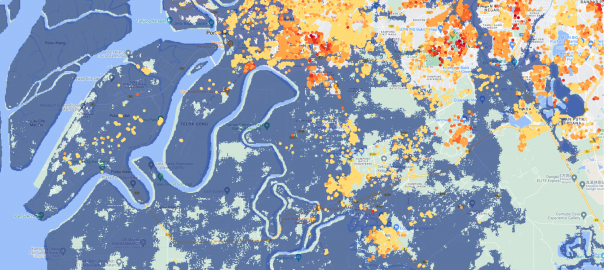

- Institutional, physical, and natural factors also contribute to vulnerability within cities, in addition to the economic and social factors. Understanding how this complex vulnerability varies within the city, geographically and with various other parameters including gender, ability, income level, remains a challenge. While data exists on global disaster losses and their impact in terms of economic output (e.g. the Gross Domestic Product), little information exists on how these losses (a) vary within cities with various socio-economic parameters, (b) affect livelihoods, (c) are concentrated amongst the more vulnerable populations and communities[xiii]. This challenge (capturing the variation of vulnerability within cities) becomes more acute when we try to account for the effect of climate change on the severity and frequency of hazards, and the effect of sea level rise on coastal cities and livelihoods[xiv].

- In many parts of the world, housing and landuse policies continue to be driven by short-term profit considerations and speculative investments in real-estate, while resisting meaningful environmental regulation and sustainable development considerations that can address.

To fully realise the advantages of increased urbanism, people will have to influence the decision-making process within their cities, to ensure that the value that is being created is not accentuating inequality but rather promoting inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable cities, partly through:

- Carrying out a regular critical review of the indicators used to assess the “health” of the city. This is needed in order to ensure that state of the environment and the ability of the people to meet their socio economic needs are part of all assessments on the health of the city.

- Underlining the notion that a city cannot do well if its environment, and the majority of its people are not doing well (as for example measured by different forms of pollution, access to common space, resilience to climate change, resilience against disaster losses, poverty, inequality, access to affordable and good quality health and education, etc).

- Highlighting the notion that “trickle-down” urban, landuse and housing policies that focus almost exclusively on “entrepreneurial growth poles” do not work. Instead, investments should also be directed at poorer neighbourhoods, communities, livelihoods and associated infrastructure.

- Highlighting the people’s Right to the City[xv]. For while International frameworks can provide evidence-based guidelines and recommendations, it remains the duty and privilege of city dwellers to call for a more inclusive and participatory urban decision-making processes.

Fadi Hamdan

Beirut

[i] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2016). The World’s Cities in 2016 – Data Booklet (ST/ESA/ SER.A/392).

[ii] Human Development Report 2016, Human Development for Everyone, United Nations Development Programme, 2016.

[iii] HABITAT III, United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, 2016.

[iv] Deputy Secretary-Remarks at the High-Level General Assembly Meeting on New Urban Agenda, UN-Habitat, 2016.

[v] Sustainable Development Goals – Seventeen Goals to Transform Our World, United Nations, 2016.

[vi] Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, UN, 2015.

[vii] Human Development Report 2016, Human Development for Everyone, United Nations Development Programme, 2016.

[viii] HABITAT III, United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development, 2016.

[ix] Human Development Report 2016, Human Development for Everyone, United Nations Development Programme, 2016.

[x] Slum Almanac, 2015/2016, Tracking Improvement in the life of Slum Dwellers, EU, UN-HABITAT, Participatory Slum Upgrading Program, 2016.

[xi] Economic and Social Inclusion to, Prevent Violent Extremism, World Bank – MENA Economic Indicator, 2016.

[xii] Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism, United Nations, 2016.

[xiii] Global Assessment Report, United Nations, Geneva 2015.

[xiv] Global Platform, United Nations, Mexico, 2017.

[xv] The right to the city, H. Lefebvre, (1996), in Writings on cities, Kofman et al, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996.

Leave a Reply