A preview of the book, Urban Planet: Knowledge Towards Sustainable Cities. 2018. Editors: Thomas Elmqvist, Xuemei Bai, Niki Frantzeskaki, Corrie Griffith, David Maddox, Timon McPhearson, Susan Parnell, Patricia Romero-Lankao, David Simon, Mark Watkins. Cambridge University Press. Available as an open source download here, or purchase as a physical book.

To secure a better urban future, we must strive to produce an integrated and actionable urban knowledge.

But broad recognition that we now live in a majority urban world—and that cities will surely determine our future—does not mean we agree on why nor how the urban era is important. More importantly, neither does it suggest how to design cities that will serve people and nature so that urban spaces are sustainable, resilient, livable, and just. It is clear that progress toward the goal of such cities will require a more open and reflective dialogue that span divides separating points of view, ways of knowing, and modes of action.

But broad recognition that we now live in a majority urban world—and that cities will surely determine our future—does not mean we agree on why nor how the urban era is important. More importantly, neither does it suggest how to design cities that will serve people and nature so that urban spaces are sustainable, resilient, livable, and just. It is clear that progress toward the goal of such cities will require a more open and reflective dialogue that span divides separating points of view, ways of knowing, and modes of action.

But how? This is the spirit of collaborative and diverse dialogue that nurtured the new book, Urban Planet.

Urban Planet draws from diverse intellectual and practice traditions to grapple with the conceptual and operational challenges of urban development for sustainable, resilient, livable, and just cities. The aim is to foster a community of global urban leaders through engaging the emerging science and practice of cities, including critiques of urbanism’s tropes. We hope that ideas about global urbanism that situate the city at the core of the planet’s future will provide pathways for evidence-based interventions to propel ambitious, positive change in policy and practice.

Most of what will actually happen across the global urban system will be down to citizens, political decision-makers, and the actions of people institutions (including governments and civil society). For us, adaptive urban knowledge and practice is imperative: a new way of thinking and acting about cities and with cities. This will require an excitement and curiosity about cities that fuels a massive scaling up and sharing of our collective wisdom about the urban world we inhabit. Good urban ideas cannot remain isolated in academia: they must be invented and re-invented on the ground, both useful and responsive to the needs of city-builders.

With this at heart and in mind, over 100 contributors, from both practice and academia, make this a book that is both idea-driven and grounded in reality. The sections below provide a glimpse into the key ideas in the primary sections of the book.

We inhabit a dynamic urban planet

Urbanization follows diverse patterns and pathways, each presenting unique policy challenges. Some urban regions are growing rapidly but others are shrinking. While mega-cities often receive more attention in global urbanization debates, many smaller urban centres are growing more rapidly. Cities do not exist in isolation: they are open systems, with various processes linking cities and their global resource/environmental hinterlands. These facts have immense implications for global sustainability.

We need to continue to develop and advance thought on urban typologies and complex systems, and understanding of the different dimensions of urbanization at regional and global scales, both at medium and long-term (beyond 2050) perspectives. However, at the same time, there is also the need for knowledge underpinning very local, place-based solutions. We’ve come a long way with more holistic approaches and frameworks, but knowledge gaps still remain when it comes to understanding politics and underlying power structures, political economy, urban macroeconomics, cultural traditions, and preferences/behavior that influence urbanization.

How do we bridge the gap between the demand for local, placed-based solutions and regional, global, and temporal insights on urbanization?

Urban systems are complex, with many interacting parts, and therefore we need to avoid simplistic indicators—hence the need for increasingly sophisticated indicators and efforts to ensure global relevance. Successive generations of indicators and multi-criteria aggregation tools have improved our ability to capture urban complexity and dynamism, though there is often a trade-off between the increased sophistication of more holistic and composite indicators and the availability of the requisite data. More integration with international agencies and governments can help develop indicators that are useful for both science and policy.

For the development of useful knowledge, we can view cities as living laboratories: Big Data, citizen science, co-production, and the data potential of social media have great potential to be of service in creating knowledge for better cities. For instance, citizen science is an umbrella term for numerous ways in which ordinary urban dwellers and community groups can engage in knowledge creation as active data collectors using everyday devices, such as mobile phones, while undertaking their normal daily activities, or carrying out specific surveys and reconnaissance activities to complement conventional research.

A persistent threat to knowledge-based city making persists. We must work to overcome inertia and entrenched interests. Greater inclusivity and multi-stakeholder engagement do not, in and of themselves, overcome these barriers, although they might help to challenge them by engaging and perhaps empowering previously voiceless and underserved groups.

Reconciling the fundamental “disconnects” of global urban sustainability

In fact, urbanization is an opportunity to increase global sustainability. But, what does it mean to create sustainability on the ground? To do this we must connect to local issues, behavior, and politics, not only global patterns since no masterplan will be locally appropriate and legitimate.

One way to focus the idea of “sustainable cities” is to prioritise the areas of greatest need, for example, the urban poor and the areas they inhabit. This addresses the most urgent and often severe aspects of unsustainability and has the potential to make a clear difference. Success will require complex tools and patience to work with the communities through inclusive and participatory or co-productive approaches.

However, it is also clear that urban sustainability cannot be achieved if current levels of consumption persist in the Global North. It is perhaps the greatest geopolitical challenge of our time: how to reconcile, in terms of global sustainability, the need for increased prosperity in growing cities of the Global South with persistently high consumption (and the related production systems) in the developed world.

To engage multiple points of view is to create more robust solutions

There are many and diverse stakeholders and actors that play a role in urban transformations to sustainability, from city officials and private and civil-society actors, to the people who live in cities. We must actively engage them. A key revelation lies in acknowledging that because a diverse agency is active in cities, we must create solutions that have wide currency, and are born of multiple streams of thought and care. Such a rich solution base can be the stepping stone for positive trajectories to sustainable, resilient, livable, and just cities.

Recognising the diverse agency and the richness of solutions they bring forward, we need multi-actor knowledge building and governance that invites new and unusual partners to play a role in urban transitions, and proposes to deepen research about relations between these urban change agents for new approaches and new collaborative and empowering means to facilitate urban transformations to sustainability. One common thread—and perhaps at the core of such challenges—is the need for merging work across disciplines, integrating other forms of knowledge, opening to multiple forms of knowledge, and embedding urban research into global policy processes.

Views from practice

For many writing from the street view, there is a great distance between academic knowledge and effective practice and city and neighbourhood scales. While the provocations from 38 designers, artists, activists, and other practitioners focus on an array of topics, they tend to hover around a set of key ideas or themes. Central to many of the chapters is the idea that the political reality of local sustainability is often ignored by academic treatments of the subject. For Mahim Maher of Karachi, this means that the concept of sustainability as it stands in New York and London is attractive but meaningless for her hometown, where there have been long periods without a mayor, there is little organized city planning and water has been sold by organized crime.

Good ideas must not remain solely in the academic realm—untranslated in common language, unreported outside of academic journals, not matched with workable solutions, and not addressing the needs of decision-makers in cities. Policy needs a human scale, and so does knowledge. The academic knowledge will mean nothing if the lives of people are not improved. For some of our provocateurs, the core Western economic model is fundamentally flawed or even broken. For example, Guillerma Ramirez, an indigenous leader from the Mapuche region of South America, believes that technical sustainability solutions without fundamental social reform are bound to fail.

Other essays point to the fact that cities around the world increasingly benefit from greater participation and activism by civil society, practitioners, and regular citizens. This activism has two key benefits. First, it facilitates the grounded practice of making better cities through not just knowledge, but action: the design of neighborhoods, infrastructure, and open spaces that better serve the needs of both people and nature. Second, participation by urban citizens in decision making and urban creation should be the driver in any connection between academic knowledge and policy. Indeed, what knowledge do cities themselves feel they need?

Persistent fault lines

First, there is lack of academic knowledge on and voices from cities of the Global South compared to the Global North, which is an apparent and common knowledge gap demonstrated across all the academic chapters (but less so the contributions from practitioners). Indeed, even in cases in which knowledge and experience from the Global South are well-developed, it often does not find its way into traditional academic forums. Even when they do, they tend to receive less attention and less prominence in the traditional academic ecosystem of ideas.

While cities in the Global South are and will be the home for most of the current and future urban populations, and they are confronted by very complex urban challenges, the reality is that more influential and dominant voices in academia are from the Global North. Books such as this one, while still imperfect in this respect, are an important advance, in which ideas and experience from the Global South are integrated into a book with global reach.

Second, there are drastic differences between the perspectives of practitioners and academics. Here it is critical to note that there are many styles, sources, and uses of knowledge that typically exist in isolation from each other. In an attempt to pursue more universal and scalable patterns and processes, academic knowledge can sometimes be agnostic on the idea of social values. It cannot remain so, as we are deeply fragmented, from Global North to South, and from rich to poor.

As demonstrated by the diverse perspectives represented in the section called Provocations from Practice, many urban stakeholders other than researchers hold deep insight into urban issues. Urban practitioners’ knowledge of what works and what does not, based on long-term experience of practice and context-specific knowledge, can be key, and an invaluable complement to scientific knowledge. But, in traditional urban literature,these distinctions only receive peripheral acknowledgment, at best. This is, in part, due to the formalities of academic publishing, which discourage the “informality” of practice. But in general, there is a paucity of forums for sharing practice-based solutions among city and communities. This is starting to change (for example, The Nature of Cities).

Visions of the cities we want

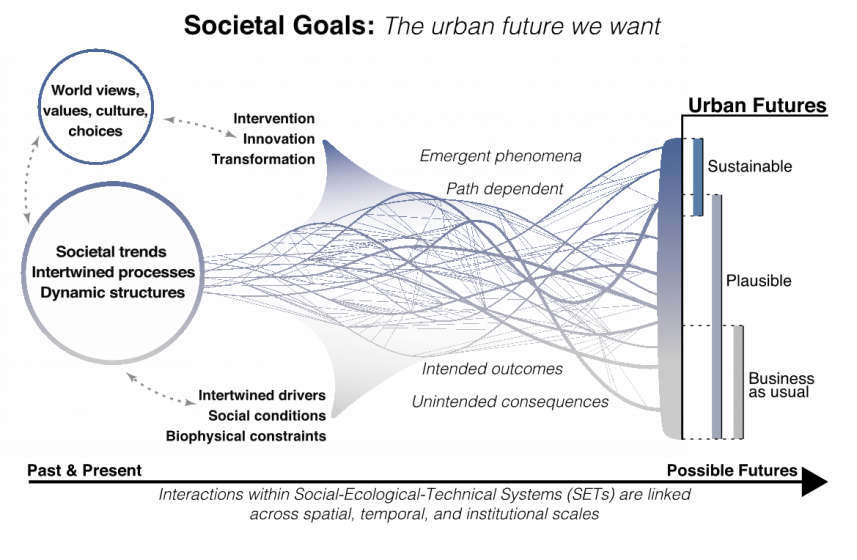

Building better and sustainable cities requires knowledge from multiple sources. It also requires visions of the cities we want that are grounded in values. High-level policy goals for cities will require science (or, at least, a new integrated urban knowledge), imagination(formulating and utilizing collective visions of the future), and open minds (understanding and embracing deep uncertainties and risks into the future).

The lack of connection of policy and science to the attachment to place by people (a lived experience) is repeatedly highlighted in the practitioner chapters in this volume. Visions need to be co-created in inclusive, experimental settings, varying from demonstrators, to civil society initiatives, to seed-projects and urban living labs across cities around the globe. Uniform across all types of cities is the need to create conditions for inclusive, just cities in which voices and aspirations across social groups are heard and considered and city-wide visions like smart cities are democratic and open for debate.

Visions, in particular, shared positive visions, can play a critical role in shaping desirable futures. Of course, visions alone are not enough. There is urgent need for action-oriented research and practice that links positive visions to on the ground transitions and transformations. While we acknowledge that the formal attribution of transformational change as a causal result of visioning is entangled with a myriad of social, political, cultural, ecological, and technological factors, examples of successful implementation of positive visions offer the optimism and empirical basis we need for replication and scaling up to the cities we want.

A way forward

Some of the tensions revealed in this book, especially between the academic and practitioner worlds, present opportunities for synergies, while others represent fundamental frictions and clashes of worldviews, ways of knowing, and modes of action. The reasons for such disparities vary across geography and communities of practice. It is not the intention of the book to present an analysis of the underlying factors (although this would be a worthy direction of research). Rather, by presenting them side by side, we wish to showcase the diverse perspectives, contrast the state of research insight with lived realities in communities of practice, and present different forms of knowledge and ways of knowing.

By doing so, we point to the need to resolve the gaps and produce new types of knowledge that integrate knowledge from applied, practical, and academic sources. There are many more bridges to cross in order to connect knowledge with lived reality. For example, does research-based knowledge truly reflect reality or does it cater to policy and practical needs? To what extent academic knowledge is translated into practice, or, more importantly, correctly translated with all appropriate constraints and caveats? In which areas do practitioners even need research? How can practice-based knowledge be better shared?

These are just a few of the important questions suggested by discussing research and practice in a single volume. Bringing these into one volume in itself is a pioneering attempt, and we hope the creative tensions presented can serve as a springboard to futher discussions.

One thing is clear: To secure a better urban future, we must strive to produce an integrated and actionable urban knowledge.

Thomas Elmqvist, Stockholm

Xuemei Bai, Canberra

Niki Frantzeskaki, Rodderdam

Corrie Griffith, Phoenix

David Maddox, New York

Timon McPhearson, New York

Susan Parnell, Cape Town

Patricia Romero-Lankao, Boulder

David Simon, Gotthnberg

Mark Watkins, Phoenix

References

Bai, X., Shi, P., & Liu, Y. (2014). Society: Realizing China’s urban dream. Nature, 509(7499), 158–60.

Bai, X. et al. 2016. Defining and advancing a systems approach for sustainable cities. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. Volume: 23 Pages: 69-78 Part: 1 DOI: 10.1016/j.cosust.2016.11.010

McPhearson, T., D. Iwaniec, and X. Bai. 2017. “Positives visions for guiding transformations toward desirable urban futures.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability (Special Issue), 22:33–40 DOI: 10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.004

about the writer

Xuemei Bai

Professor Bai is a professor in Urban Environment and Human Ecology at Australian National University.

about the writer

Niki Frantzeskaki

Niki Frantzeskaki is a Chair Professor in Regional and Metropolitan Governance and Planning at Utrecht University the Netherlands. Her research is centered on the planning and governance of urban nature, urban biodiversity and climate adaptation in cities, focusing on novel approaches such as experimentation, co-creation and collaborative governance.

about the writer

Corrie Griffith

Corrie is Program Manager for the Global Consortium for Sustainability Outcomes (GCSO), based at Arizona State University.

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

about the writer

Timon McPhearson

Dr. Timon McPhearson works with designers, planners, and local government to foster sustainable, resilient and just cities. He is Associate Professor of Urban Ecology and Director of the Urban Systems Lab at The New School and Research Fellow at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies and Stockholm Resilience Centre.

about the writer

Sue Parnell

Professor Sue Parnell is an urban geographer in the Department of Environmental and Geographical Sciences at the University of Cape Town and is a founding member of the African Centre for Cities there.

about the writer

Paty Romero-Lankao

about the writer

David Simon

David Simon is Professor of Development Geography at Royal Holloway, University of London and until December 2019 was also Director of Mistra Urban Futures, an international research centre on sustainable cities based at Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden.

about the writer

Mark Watkins

Mark Watkins is Program Manager for the Central Arizona-Phoenix Long Term Ecological Research Program, part of the US LTER Network.

Leave a Reply