New ideas such as green roofs could add a decent amount to Cairo’s green spaces, given the huge amount of abundant flat concrete roofs. The idea has triggered the government’s attention in the form of two national campaigns.

Why do we build more cities in the sand?

How is my government dealing with the city’s overpopulation? The answer is simple, according to their perception: “lets conquer the desert and build new cities!”. There is also a paradoxical situation in which the state constantly attempts to “green the desert”, often with little success, while on the other hand failing to strike a balance that allows for the protection and increased productivity of existing agricultural land.

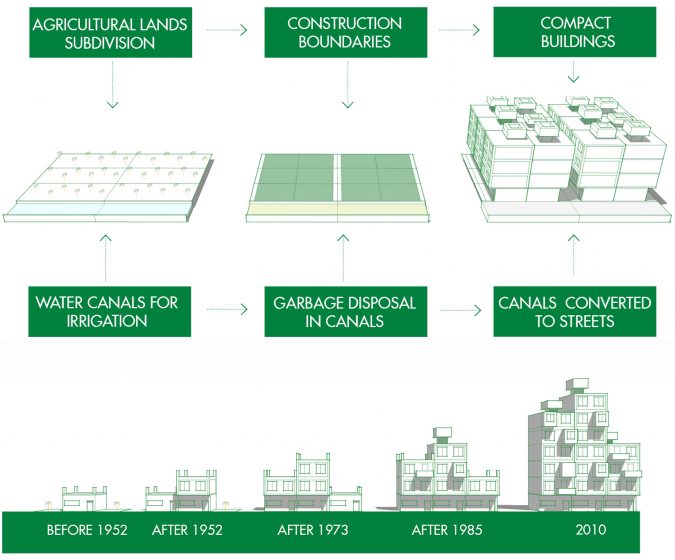

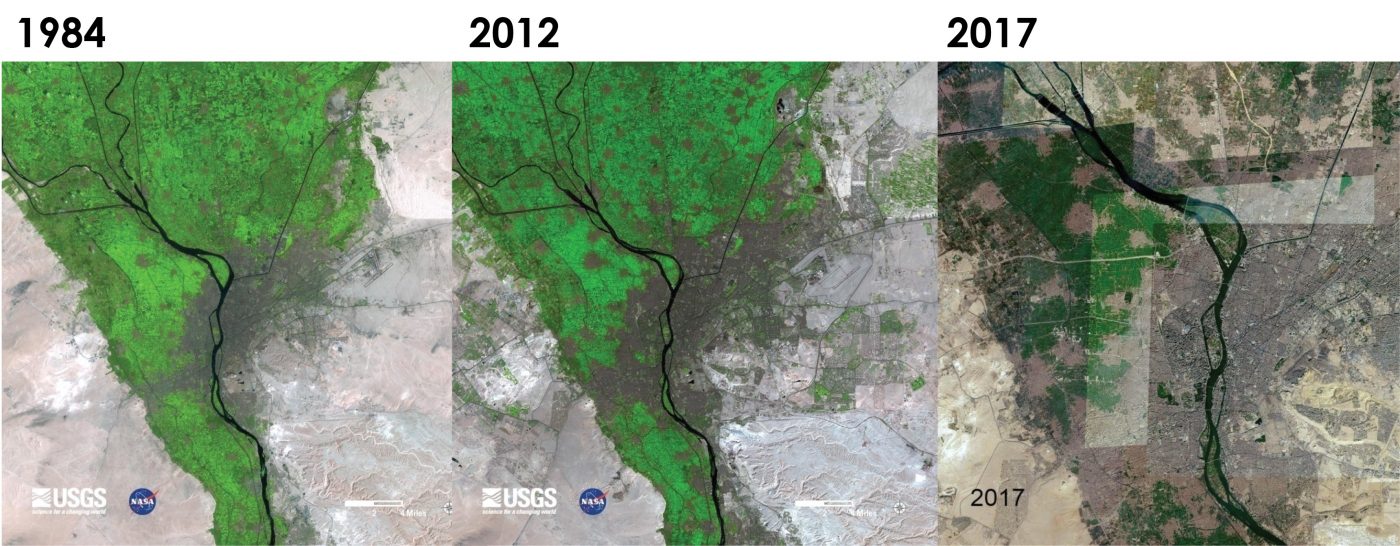

To escape from the congestion of central Cairo with all its challenges, there are two patterns evolving to absorb the increasing population. The first is building illegally on existing agriculture land on the peripheries of Cairo—inside the delta, which is known as the “breathing lung and the food basket” of Egypt. The absence of effective laws that prohibit agriculture land encroachment, and the leniency of the government in dealing with violators is resulting in the continuous increase of such activities. This is also exacerbated through time when lands are being inherited by more people and fragmented to smaller plots. Through time the living style has changed and farmers owning small plots of agriculture lands are realizing that constructing/selling houses is an easier way of making money, compared to agriculture activity, which usually requires continuous interventions, in terms of technology, labor, operation and maintenance and the return of investment.

This pattern creates lots of challenges in terms of open and green spaces. Those lands were originally divided according to the agriculture basin subdivision and have been transformed through time to unplanned dense urban dwellings. The aftermath of this incremental transformation could be described as “A Transformation from active agricultural producers to intense inactive consumers”.

The second pattern is the governmental vision to expand toward the east and west of Cairo, away from the river, building new cities in the desert. David Sims, in his book “Understanding Cairo”, describes new desert cities as “an investment bubble; and a vehicle for the dispensation of patronage and favors”, referring to desert real estate investors being either behind the bars or on the run. The problem is that very few state funds have gone to the development of Cairo’s existing informal settlements, which are the home of two third of Cairo’s population, whereas the few, largely elite suburban inhabitants out in the desert have seen countless millions poured into their communities for the development of those new desert cities.

How are green spaces defined in Cairo?

Cairo’s share per capita of green spaces—1.7 m2/capita—is much lower than the international norms and standards, and according to the study “ Review of green spaces provision approaches in Cairo, Egypt” by Merhem Kelleg is still lower even when compared to more arid cities like Dubai. WHO recommendations of 9 m2/capita for a livable environment and 50 m2 for ideal living conditions. This 1.7 m2/capita is not evenly distributed among Cairo’s population. More than half of the city’s population only have 0.5 m2/capita; 70% of the population experience less than the city average of 1.7 m2/capita. In other words, the little green and open space there is concentrated in just a few neighborhoods.

Recreational green space has historically been provided in Cairo at a very low level compared to other cities globally and in the region. Much of the green space that is provided—by municipal government or private entrepreneurs—is provided as a private amenity, enclosed and charged for either by membership fee or entry toll.

A study conducted by Kelleg about green spaces provision in Cairo revealed that two thirds of the green spaces areas in Cairo is provided by the private sector, when the other one third could usually be found in private sports clubs. The focus for private green spaces can be clearly seen in either sports club or gated residential communities. Recently, a growing number of gated communities has been developed especially in the new desert cities East and West of Cairo. These compounds mainly target high income families promising safety through fencing the community with big concrete walls and trained security staff who controls the entrances, with a promise of bringing a better quality of life. In their master plans they tend to focus on the presence of vast green to promote their projects, usually using a reverse psychology of the contrast image that you should run away from, a polluted, chaotic and densely populated non green city of Cairo.

Sporting Clubs are private recreational areas that provides reasonable amount of green spaces to individuals, but with annual memberships. They provide leisure environment and direct access to well managed and maintained landscapes and green areas. Those clubs are usually the escape for residents of Cairo’s middle and upper-class families.

There are other green spaces that evolved in Cairo through partnerships between different entities, adding to the total area of greenery in Cairo. Most of them charge entry tickets, but as the project stakeholders have different agendas and aims, the prices of the tickets vary a great deal: some are relatively affordable for a great percentage of the public like Al Azhar park, being implemented in partnership between Agha Khan foundation, the Egyptian Government as well as some local NGOs. The park, developed at a cost in excess of USD $30 million, opened its gates in 2005 as a gift to Cairo from Aga Khan IV: a descendant of the Fatimid Imam-Caliphs who founded the city of Cairo in the year 969. The low entrance ticket price allows for diversity of socioeconomic strata to benefit from the green spaces inside the park, compared to other green spaces that usually charges a relatively high entrance fee. Despite the important role those green spaces play in adding to the total share of green spaces, they cannot be considered a reliable source for green space for the public as they are designed for specific stakeholder and could be categorized as semiprivate green spaces.

The government has only one centralized entity responsible for the creation and management of any city-related green space. This entity—“ The National Authority for Beautification and Cleanliness”, NABC”—does not get strong political and financial governmental support compared to other local authorities. The authority is also concerned with solving more pressing issues in Cairo, including solid waste management, with the support of the ministry of Environment.

The absence of strategies for green spaces in the city, a lack of policies and governmental support, and the general unawareness of the importance of landscape to the surrounding built environment contribute to the currently poor situation of green spaces Cairo.

It is also obvious that the social aspects of green spaces is mostly overlooked, which affects the livability and social attitudes in Cairo. “Do not ask me about sensations in green spaces because I have lost them a long time ago. My only concern is to feed my family. Green spaces and sensations is a luxury, which I cannot afford even thinking of”, answered one of the interviewees to a question of “How essential to people’s daily lives are the feelings evoked by green spaces?” according to detailed PhD research done on the dynamics of urban green space in Cairo.

In the same study, when asking the residents how do they perceive the problems of existing green spaces, the most common answers were: “Social Behavior” (or misbehavior of certain users in terms of respecting others); “Security” (or lack of nearby police stations and security guards); and “Maintenance” (the lack of essential public services, including seating and site furniture). These problems lower the use-value of green space to residents and may reduce the visiting frequencies, especially for children, families, and women.

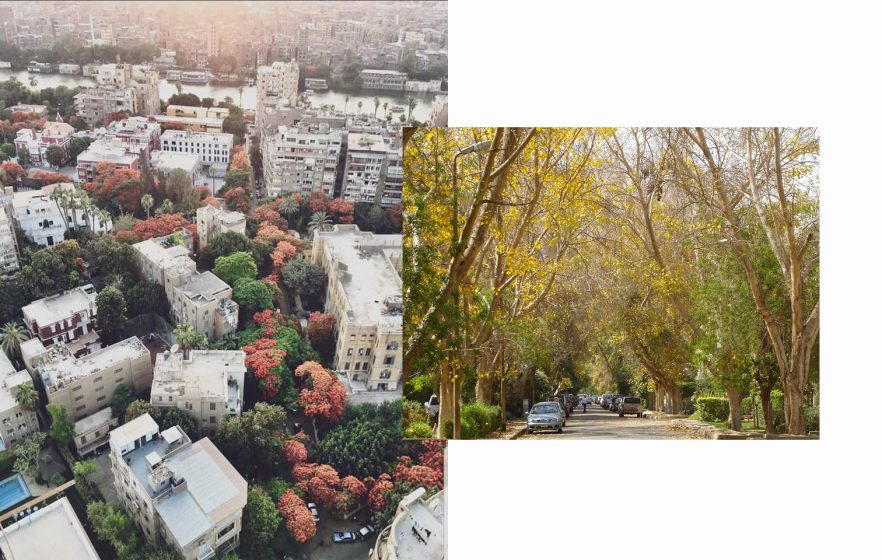

Just because we are a sprawling concrete metropolis in a desert does not mean we don’t need some public greenery in our lives. And luckily, there are a few places in Cairo where you can find just that, even if you don’t belong to a sporting club. Districts like Zamalek and Maadi are considered relatively rich in green spaces, However, there is obvious inequality in terms of green space distribution when comparing those districts to other middle/low income ones, situated only a short distance away within the boundaries of the same city.

Is it possible to revive Cairenes’ biophilia?

Biophilia is a hypothesis suggesting simply that we as human beings have a feeling of love to all what is living, and that we always seek connections with nature and other forms of life. How can people living in Cairo define their own Biophilia given the challenging urban patterns they live in?

Most of the new Cairenes generations nowadays are not well connected to the natural environment. It could be due to the struggle of the normal Cairo resident in finding a simple and defined access to public green spaces. There is so much pressure on land in Cairo that green spaces become sidelined as the least important use of the land.

As described by the cofounder of Cairo Lab for Urban Studies, There could be two possible models to revive green spaces in Cairo and present it to the public in a sustainable manner. One could be having some commercial activities attached to existing parks, such as concession stands or cafeterias, which would generate income. A park of a small fee ticket for the general public would not impede residents from enjoying green spaces, and at the same time high end restaurants could be introduced to subsidize such tickets and work on making this park as much alive as possible.

The other option is what is called “Privately Owned Public Space” or POPS, a model introduced in many cities around the world and very popular in New York City. It works by inviting the private sector, including banks, companies, law firms, and large cooperation to work inside the city center itself. A part of their branding could be to have a little bit of an urban park outside the premises or headquarters, and it becomes part of their marketing image to dedicate some of their property to public use.

Those two ideas are usually welcomed by the government, given that the budget of public green spaces is always way less than what is really needed for the city and this could support many agendas to improve the livelihood in the city. The challenge facing the government is usually how to create a sustainable public green space, that are free of charge and in good shape for the public. Collecting entrance fees and privatization of public spaces could partially solve the issue of regular operation and maintenance through the acquired funds, however, it contradicts with the realization of environmental justice and proving that green spaces is a free and substantial right for anyone living in the city away from any kind of discrepancies. Given the existing socioeconomic conditions in Cairo and the increasing percentages of urban poverty, those ideas will not find acceptance from a big sect of the Cairenes urban fabric, who are focused on basic needs provision, rather than paying fees for a “luxury” setting as perceived.

Thinking out of the box… up to the top of it

New ideas such as green roofs could add a decent amount to Cairo’s green spaces, given the huge amount of abundant flat concrete roofs, and given the fact that Cairo holds at least 40 % of the total amount of Egypt’s built-up area. The idea has triggered the government’s attention, as they launched two national campaigns with the support of the Ministry of Environment and Cairo Governorate, to Green as much governmental, public and residential buildings possible. The idea is appealing and is expected to have a positive impact on the urban life in Cairo if applied on a larger scale.

Roofs in Cairo are usually used as storage space. In conventional residential buildings any tenant can have an access to the roof and may usually use some storing space for free upon agreement with the building owner. Turning any residential building’s roof green, which will then be used, operated and maintained by all tenants would require a cost sharing scheme alongside the approval of the building owner.

In Cairo’s informal settlements the situation is not simple. The land was historically illegally squatted and converted into residential buildings. The problem arises when apartments are sold to individuals, and the roofs are no longer owned by anyone, but converted in to a shared ownership for all the building tenants. In informal concrete buildings of 10 floors with usually no elevators, a green roof might be a pleasing idea for tenants living at the top floors compared to the ones living in the lower ones. Cost sharing to build a green roof in this case is still not easy to apply and would require more equal incentives for all tenants.

Green roofs could be connected to agriculture production and this could be an incentive supporting the spread of the idea over different social strata. The benefit can start with decreasing food expenditures and creating smart agriculture job opportunities, to being able to produce healthy and fresh food, as well as reconnecting the people again through a Community Shared Agriculture (CSA) model. Using environmentally friendly materials that are durable, locally available and cheap is the key for disseminating the concept of productive green roofs in Cairo.

Rooftops in our urban centers represent a strong potential of currently underused space. The transformation of these urban rooftops into a socioecological resource through an increased implementation of green roof technology is becoming a normal practice in many cities around the world. As a result of the growing interest in urban agriculture practices, a new type of green roofs is emerging. It is no longer a question of whether or not green roofs should be implemented, but rather how their impact can be maximized beyond their recognized environmental values. Green roofs usually target densely populated cities and urban agglomerations that lack open/green spaces. This is exactly where the presence of agricultural lands is rare, and the proximity to fresh and nutritious produce is diminishing. The development of Productive Green Roofs could transform conventional green roofs into business-driven systems if properly studied and implemented.

Lufa Farms project in Montreal, Canada and Gotham Greens in NY and Chicago are excellent examples of utilizing underused roof spaces in creating a multidimensional agriculture business opportunity. Those projects created a trend that will one day impact the regional agricultural market in Canada and the US if properly disseminated. They have provided a successful attempt to integrate rooftop agriculture practices in urban areas and solely develop through an independent business model.

The fact that those models lies under sophisticated greenhouse systems that used high technology components does not overlook the potential of low tech rooftop farming systems, if the proven agricultural measures are followed. However, It is logical to state the difference in capabilities between simple and complex agricultural techniques.

Nowadays most of rooftop agriculture projects in developing countries is planned on a small/household/pilot scale. Most of the larger scale rooftop farms exists in the developed world especially North America, where in most cases the produce is meant for private use rather than for the market, or is processed, cooked and/or sold to another business in the same building (a restaurant with a kitchen garden). Some rooftop farms cooperate with regional farmers to increase product variety and use common marketing and distribution channels. The commercial farmers in developed countries compete on the basis of quality rather than price. It is important to state the difference in market demand between developed and developing countries. Large scale Productive Green Roofs planned for informal settlements in Egypt would have a different ideology, design approach, marketing techniques, and selling strategies when compared to the ones in Canada or the United States.

There is no argument that Urban green spaces should be considered as a basic right and a not a luxury setting. With the complexity and diversity of our cities morphology, the perceptions usually change on how we design, manage, and deal with our urban green spaces and channel their use according to our different desires and needs.

Cities are different in their urban fabric and morphology, but we all share being human, and biophilia should be rooted inside all of us, no matter where we belong.

The question is still on for Cairo: What should we do to revive our Biophilia and strengthen our connection to the environment and create sustainable development opportunities in a city growing in the desert?

Abdallah Tawfic

Cairo

References:

Aya Nader, 2016: “Oases in the Dust: Investing in Cairo’s Green Spaces”

John Harris, 2012 : “Urban planner David Sims explodes myths on Cairo’s dysfunction”

Merhem Keleg , 2018 : “Review of green spaces provision approaches in Cairo, Egypt”

Leave a Reply