The compound disasters of the coronavirus, racial injustice, and climate change are shifting our relationships to the city and its public spaces. Who will be the transformative agents that can help address these issues?

But there remains a crucial need to understand how these changing relationships to nature, society, and the public realm are affecting us individually and as a society. As such, we need qualitative approaches to document our lived experiences, with all their emotion, affect, embodiment—and dis-embodiment. We need to walk, talk, observe, write, and draw as living, sensing beings in order to understand how the pandemic takes place. We need to remember the head-spinning disorientation of the past three months, to reflect on how it unfolded over time and continues to unfold. Since 13 March 2020, we have been keeping a small group journal with our set of experiences of our communities—both our local communities of place and the virtual communities of which we are part.

Read the second essay in this series here.

Despite our shared experience of racial and economic privilege, each of us is sheltering in a different NYC neighborhood across Brooklyn and Queens, and we also all have different family configurations, risk factors, community networks, and local open spaces and built environments available to us that inevitably shape our experience of place and the pandemic. Out of our collective journaling—separate but together—have emerged some shared patterns and individual insights. We are mindful and reflexive that we are just four people out of the billions experiencing this global crisis- and therein lies the rub, the desire to zoom back out to aggregated pictures. But we need both focal lengths- the macro and the micro, the bird’s eye and the worm’s eye view. So in sharing these reflections we do not mean to universalize, but rather to offer—to ask—does this resonate with your experience of nature and community in the time of COVID-19? Why or why not? We invite others to document their lived experiences of COVID-19—as we need this collective reflection now more than ever.

We offer our reflections below in four thematic parts alternating among each of us. We are cognizant that the crisis continues to unfold and are humble that our particular stories are not really the ones that need to be told the most right now. But if we inspire someone else to write, to reflect, to talk, to share, then we have achieved our aims.

I. Sirens, Birdsong, and Social Media: Soundscapes and Digital Connections

Shelter-in-place, stay home, wear a mask, do not gather, maintain social distance: all of the basic steps that are involved in flattening the curve and slowing the spread of the virus also have the impact of isolating and atomizing us into our household units—whether we live entirely alone, with partners or roommates, or our families. We find ourselves spending more time in our homes and personal spaces than perhaps any other time in history. But of course we are not alone, we are separate together, hyper-connected via the digital realm and the mediasphere. In fact, it is hard to disconnect. In an interview with author and artist Jenny Odell on an Ezra Klein podcast, she discussed how the only distinction now between her work life, social life, personal time, or family time is now in her mind—it is all happening compressed into a single space—and this resonated with our experiences. This lack of physical space and separation of activities is mentally fatiguing. So our minds rattle between stressors and the mundane—the dire news of the day, the work tasks to complete, the groceries to purchase, the friend who was ill, and those who passed. We remain ever-mindful that this sort of fatigue is a luxury, compared to the physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion faced by frontline and essential workers.

While digital connections feel like the most omnipresent and obvious connection to the “outside world” — other flows permeate our homespaces as well, including some that operate on deeply emotional registers. In particular – sound is able to travel at a distance and can reach our ears and minds even without our directed attention. At the peak of the pandemic in NYC with so much less car and air traffic, the city soundscape was altered. Less of the hum/drum of everyday street noise, but the wail of sirens was unignorable. Daylong conference calls and zoom meetings would pause when the uncomfortable reality of a siren came through someone’s speaker. Polite muting did not remove the painful reminder— thousands are ill, thousands are dying. Yes, this pandemic is happening all around us while we sit, sheltered in our homes, grateful for and worried about those unable to do so.

At the same time, many began to notice the subtle melodies of birdsong—a reminder that nature, life, and diversity are here and present all around us. When the shelter-in-place order started in March, our movement was slowed and outdoor spaces were essentially removed for many of us. At the same time, the world was waking up to spring while we were inside. The space in which we notice things has gotten smaller. Here are some journal snippets around this intimate nearby nature:

Michelle:

20 March 2020. Some of my own reflections on my relationship with the environment right now. I haven’t left my apartment in 2 days. I went to the park on 18 March after work and it was too crowded to feel safe. There was a weird frantic energy in the air. Normally I am a “Leave No Trace” person, but I couldn’t stay 6 feet away from anyone without diverging onto the grass.

I am opening my window every day until it gets too chilly. I can hear my neighbors’ laughter and conversation, but I can also hear the birds. The limited nature soundscape I have is so critical. I am not sleeping well and I can hear when the robin starts singing at 3 or 4 am—well before light. It is only daylight when the house sparrows and starlings start chiming in. That robin is a symbol of spring and hope for me.

8 April 2020. I opened my bathroom window last week and found twigs dropped by a pigeon building its nest. I looked out the window at my other sills and found even more twigs on another sill. Normally, I don’t pay attention to these birds—I am more excited about warblers in the park. But now I have an apartment list instead of a yard list/park list and am birding by sound mostly.

I see on social media that my friends who never birded are becoming birders and my birder friends are becoming backyard birders. I talked with my friends about what if I am still inside when the blackpoll warblers migrate through—at least I can hear them when they will be in the park (usually migrate through later than other birds heading to the Arctic in mid to late May).

24 May 2020. Walking around my neighborhood park, I hear my first blackpoll warbler’s high pitched trill. We are still inside—we have been inside the length of spring migration. Last week my friend texted he heard one in Inwood Park in upper Manhattan, so I knew to be on the lookout for them.

II. Rainbows and Cowbells: Signs of Solidarity and Gratitude

What are the messages that we share with our neighbors and the public during the pandemic? Signs in apartment windows or yard signs on residential lawns are vehicles for messages that we wish to transmit—they cross the threshold from our private sphere to the public realm. Collective messages of solidarity and gratitude literally rung out from the rooftops through the evening cheers that developed over the course of the shelter-in-place. These visual and auditory signs and signals are part of how we navigated this crisis, articulating our shared values and sending the message that we are not in this alone.

Lindsay:

On 17 March, I journaled about window rainbows for the first time. My nieces, sheltering with my parents in suburban Annapolis, Maryland, made a large front-yard rainbow saying “Tutto Va Bene” in reference to the Italian practice of children drawing these messages of hope and putting them in their windows during lockdown. On March 19, someone in my local Facebook mom’s group made mention of a google map of rainbows, so kids could do virtual “scavenger hunts”. Since the group was based one neighborhood over, when I first checked it there were not any rainbows in my neighborhood. We made a point of taking a long family walk with my daughter in a stroller to find and photograph as many rainbows as we could and started a digital photo album just for our “Rainbow Shimmer”. Two months later, that map has spread across the country and world. But we don’t need a map—there are rainbows in almost every window in my neighborhood—as well as chalk drawings and even a street tree festooned with rainbows, but I still find myself taking pictures. The emotion I feel each time is mostly tenderness—I feel cheered by the messages of hope and thanks for essential workers, but I picture the millions of children, sheltering at home with their bewildered parents, and my heart aches and aches.

Every night at 7pm, we open up our window and ring a cowbell. My toddler ends this ritual with the phrase I taught her: “Thank you workers, thank you helpers” as we join millions of people around the world in thanking frontline and essential workers. Our neighborhood is relatively quiet, all and all, once in a while we hear a few other bells, pots, pans, and claps, but I have seen videos from other neighborhoods around the city and the world that ring out with song. Who are we thanking? The healthcare workers, of course, but all city agencies keeping us safe: fire department, trash collection, as well as essential workers delivering food, mail, and other goods.

This local street art in my neighborhood captures the broad range of people we need to thank. I make a point not just of ringing my cowbell, but of personally thanking these workers when I see them. I contributed to a fund that was set up to help our postman purchase his own PPE—a necessary, but insufficient step toward protecting an essential worker. Frontline workers themselves have noted and protested that applause is not enough, they need protection.

Erika:

On 19 April I walked over the big retail chain hardware store near my neighborhood. I was desperate to see if I could find something colorful to grow in planters on my roof. There was a sign thanking emergency responders and a place to sign your name with appreciation. The NYPD, EMS, and the Dept of Sanitation were all listed…and then I saw the logo for the NYC Parks Enforcement Police (known as PEP officers). This was the first time I personally ever noticed NYC Parks acknowledged on a first responder sign. I smiled. Although the gates are locked, each and every day since this all began, there has been a park worker that shows up in the park across from my apartment. This person sweeps, cleans, and keeps order until we can enter again. I am very grateful for her work.

On 21 May: I was on a conference call today and a colleague who runs a citywide stewardship program shared that she was disheartened. “We were denied our spring this year,” she said. Her frustration was because she knows that when people volunteer in the parks they do more than care for the vegetation, they tend to care for and learn more about each other. I was feeling down about that too. We talked about when and how the city might collectively mourn: When would be the right time? What would this look like for parks volunteers? Digging, planting and pulling vines and being in the company of others amidst a nature where life and death cannot be denied.

Lindsay:

On 21 May, the Empire State Building and other NYC landmarks were lit up green to honor and thank park workers, under the campaign #GoingGreenForParkies. Monuments in San Francisco were also lit green that day for the same reason, and I saw some social media traffic about wearing green as far away as Honolulu. This reflects a public recognition of the important work that park workers are doing and have been doing each and every day.

III. Care Work: Mutual Aid and Stewardship

Prior to COVID-19, much of our shared research has focused on civic stewardship—acts of care-taking and claims-making on the local environment. With this work, we aim to better visualize and amplify the work of local groups in advocating for, maintaining, and educating the public about the environment. We have also examined the ways in which environmental stewards reorganize and respond to disturbance—be it hurricane, flood, tornado, September 11th, invasive pest, or economic downturn. While the pandemic is unprecedented in its spatial extent and cascading public health, economic, and social impacts, it is another form of disturbance to which these local groups and networks adapt and respond.

Most visibly, we have seen the rise of mutual aid groups—many of them wholly new operations, some of them organized on the heels of prior organizing from Hurricane Sandy, which also build on the organizing of Occupy Wall Street. Even before stay-at-home orders were passed, when it became clear that many New Yorkers would be struggling—physically, emotionally, and financially—as a result of COVID-19, community members came together to prepare. Many have memories of responding to past disasters, from 9/11 to Hurricane Sandy, by activating social networks and coming together to exchange resources and hold space. Without the ability to be together physically, organizing quickly began online and via flyers posted on neighborhood streets. Over time, many became networked and began exchanging ideas on how to do the work of helping neighbors.

Whether initiated by local elected leaders, community based organizations, or residents within a building, most early efforts focused on checking in with older adults and other vulnerable populations. Establishing these social connections, sometimes through something as simple as a phone call making sure a neighbor has enough food for the week, can create a lifeline in a crisis. As the death toll ticked up and unemployment rates increased, it became clear that amidst uncertain fiscal budgets and philanthropic support, local organizing would need to fill longer-term needs. Mutual aid groups across the city are now struggling to figure out how to become more sustainable. In Crown Heights, requests for grocery runs are coming in so quickly that there is a backlog of at least a month. The level of need is high, but is it realistic for a group of neighbors, each with their own personal quarantine challenges, to fill the gaps left by the many closing food pantries and dwindling social services?

Michelle:

Because of health concerns, I have only volunteered virtually. I joined my neighborhood’s mutual aid group in late March and have watched it evolve over time, becoming more organized, networked, and complex, as it responded to more community needs and more volunteers. Seeing the volunteer numbers climb has been inspiring. I have called elderly neighbors to check in on them and, for the month of April, served on the dispatch team. Every week when I signed in to my shift, community needs had expanded, available resources had changed, and the mutual aid group was hard at work with evolving dispatcher guidelines for how to assist neighbors in need. Mutual aid groups were coordinating across neighborhoods, yet I observed that not all neighborhoods in NYC had a specific group. What is the social infrastructure a community needs to be able to establish, maintain, and expand such efforts? My neighborhood already had a strong civic-minded tech community; many of them have volunteered to create systems that have enabled communication and organization for mutual aid.

Laura:

So far all of my volunteering has been virtual. As a healthy, able-bodied young person, I struggle with finding the balance between staying home to protect myself and others and assuming some risk in order to support those who cannot safely go to the store. In the early days of quarantine, I eagerly signed up for any and all opportunities that came through my inbox. I shared my name and phone number with neighbors on a list of potential errand-runners circulating in my building. I also unknowingly signed up to make phone calls to seniors in Chicago, and organizers assured me that my actual location was not important—what does distance even mean anymore? Later, I was matched with three seniors here in Brooklyn, whom I called and connected to various services and resources I hoped would be helpful. The phone conversations I had were brief but pleasant, and everyone seemed to welcome the chance to connect. I have also joined my local mutual aid group’s intake team, responding to requests for groceries and matching them with volunteers who can go to the store and make contact-free deliveries. I recently returned a call to a neighbor who had reached out back in April, but she was still in need of basic food items. Seeing the update that her groceries were delivered felt like a tiny victory. It is moving to see people come together in times of need. Other volunteers in the mutual aid group have expressed a deep appreciation to the online community of responders. The woman who led my intake volunteer training said that since becoming out of work due to COVID-19, this has become her job. But what happens when she goes back to work and neighbors are still going without food? So much more is needed in order to support ongoing community building.

While civic stewardship groups have their usual territories and ecologies that they care for, in the face of crisis and our changing reality—we’ve observed their ability to be nimble and adaptive to meet pressing needs of their community. Updating fieldwork protocols, adjusting workforces, cancelling or changing public events, providing educational content online, and a dire need for resources are just a few of the currently emerging changes. Gowanus Canal Conservancy canceled its public events, but set up socially-distant stewardship supply pick-up with public health guidance on how to safely engage. Other local neighborhood organizations focus on serving their communities in a range of ways that include environmental stewardship and social service provision—we see these groups playing key roles as neighborhood “hubs” in providing access to information, resources, services and programming. United Community Centers in East New York is host to the East New York Farms! Youth agriculture program. While their in-person programming was canceled this spring, they focused on being a conduit to their network—providing information on emergency food relief, connecting to city services, and ensuring that their residents were counted in the 2020 census. Astoria Park Alliance, with a focus on stewarding a particular park, has focused on safe use and access of the park, through signage and online advocacy around road closures.

It is not surprising to find that several well-organized groups are in areas that were hard-hit by Hurricane Sandy, such as Red Hook, Brooklyn and Far Rockaway, Queens. Red Hook Initiative is engaged in local, resident-led response, focusing on the neighborhood’s most vulnerable residents, particularly those in public housing, as well as the youth population of the community. Their services and programs range widely from providing food relief to partnering with the city DOT in hosting an open street on W9th Street. Rockaway Initiative for Sustainability and Equity is adapting its programming to include participating in collective mask-sewing efforts, funding PPE for hospital workers, offering information about gardening and foraging for the public, and collaborating with a regional farm to provide free organic produce for Rockaway families in need.

These groups do not work alone—they organize coalitions, campaigns, and networks. For example, a group of conservancies that work closely with the NYC Parks Department organized a report on the impacts of COVID-19 on their operations and services. This report led directly to the establishment of a Green Relief and Recovery Fund with support from multiple philanthropic organizations as well as the general public. The crowdfunding organization, ioby, quickly established matching funds and resources to tailor their platform for mutual aid and community COVID-19 response. Civic organizations like ioby function as “brokers” that help support local leaders and foster emergent groups. At a neighborhood scale, the Guardians of Flushing Bay is a stewardship group that works near the epicenter of the outbreak—in Flushing and Corona, Queens. They organized a crowdfunding campaign to raise funds for groups providing direct relief in their watershed, showing evidence that these groups are not solely concerned with environmental quality, but are involved in supporting community well-being and quality of life in nimble and collaborative ways.

IV. Flowers and sidewalks, backyards and parks: Accessing hyper-local nature

As the days passed and the weather warmed, signs of spring became omnipresent. With the luxury of free time, neighborhood walks became a daily or weekly ritual for us. And with this shrunken geographic sphere came a heightened attention—to where the buds had opened, to which front yard had lilacs you could reach from the sidewalk, to which side of the street was warm and sunny for an afternoon walk. The public realm of the street trees and sidewalks is our most immediate access to hyper-local nature. So we notice it all: the lovingly tended flower beds and the unsightly spots where discarded masks and trash accumulate with the decreased street cleaning. Flowers were coming up out of street tree beds—a sign of planning ahead; gloves are left on the street, but the tree beds themselves look cared for. These walks along well-known territory changed over time as leaf out began, as daffodils gave way to tulips and pansies in the street tree beds; at the same time, the people on the street changed, with more people out and about now once there was talk of reopening and nice weather.

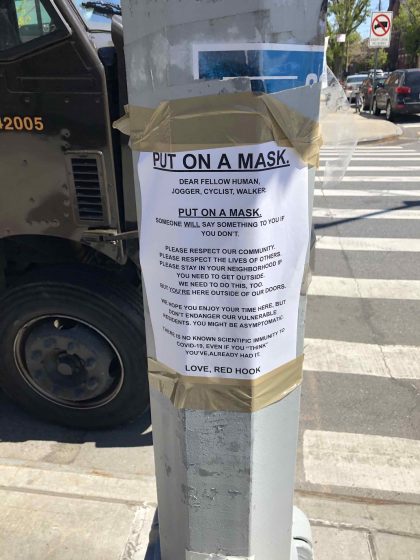

Nobody and everyone “owns” the sidewalks. They became the space where people congregate, alone with a lawn chair, spaced apart with paper-bagged beverages, in family units. Strangely, in this dire time, the public realm comes to life. But they are also spaces of friction, these sites of encounter. Who shoots an ugly glare or a sharp word to an unmasked jogger, Who steps aside for whom into the roadbed? Public shaming and enforcing of norms starts to happen with handmade flyers that appear on fence posts. These signs are messages that set up expectations about how and for whom access to the public realm occurs. In our past research, we look to the messages that the public adds to our shared spaces—like parks and sidewalks—in order to “read the landscape” for these emergent and informal norms. In the time of COVID-19 we are reading the landscape for how we navigate a changing experience with public space in the time of masking, social distancing, and closures of most of our commercial establishments

Laura:

Beyond the sidewalk are the privately owned public spaces—the front yards, stoops, backyards, and patios. In NYC, only a select few have access to these sorts of oases. Backyards have become a symbol of privilege in the pandemic. The ability for some city dwellers to safely get some fresh air by stepping onto their private balcony, or even to escape to a second or third home to comfortably quarantine is a stark reminder of the many disparities exacerbated by the virus. For those of us with access to shared private spaces, a new kind of negotiation of space is necessary. Sometimes, this means having to formalize previously unstated rules and norms. What in the “before times” might have turned into a moment of socialization between neighbors waiting to use the grill in a shared backyard is now distilled into a list of rules about the number of family units allowed in one place at a time.

And then there are the parks. And they remained open—with the exception of playgrounds that are full of surfaces that could not be cleaned regularly enough to be safe. Open and accessible to all— in theory, but the reality of that access looks very different depending upon a number of factors. Some of the issues around park access depend upon the geographic location, size, design, and programming of parks (see NYC Parks Framework for an Equitable Future; New Yorkers for Parks’ Open Space Index; TPL ParkScore). In the time of COVID-19, playground and recreation courts are considered to invite non-social distancing behaviors, while a larger park with a forest canopy or open meadow is deemed more suitable for solitary or small group activities including hiking or birding. Other factors related to access depend on how safe residents feel using a park given their race, ethnicity, gender, ability, or age (See Finney 2014; Sonti et al. 2020; TPL Parks and the Pandemic). On 2 May 2020, we read news and twitter accounts of disparities in policing between park goers who were white or people of color. On 7 May, Mayor deBlasio denounced the racial disparity in social distancing arrests, and on 8 May the City announced it would limit visitation and apply social distancing measures at Hudson River Park and Domino Park, two crowded parks in largely affluent, white neighborhoods (see images). The critical point here is to plan purposefully for equitable and inclusive access, especially as we move into the summer season with higher temperatures. Public green spaces may offer the only respite for those suffering from stifling summer heat conditions

Lindsay:

Living in my neighborhood for 14 years, I had never seen my local park more crowded. At the start of the lockdown, the police drove their cars through the park, blaring a loudspeaker message about social distancing. As time wore on, they came out of their cars, walking, mostly carrying masks to give away. It struck me that there was no reason that this particular role necessarily needed to be played solely by the police. I read that NYC Parks is staffing up with a large cadre of social distancing ambassadors. We could imagine an expanded green workforce that is responsible for the care and maintenance of both our parklands and the health and safety of the visiting public.

The 25 May racist incident in which Amy Cooper, a white woman with an off-leash dog, threatened to call the police on Christian Cooper, a black man who was birding in Central Park’s Ramble who asked her to leash her dog, revealed deeply ingrained, systemic racism that shapes who feels safe in parks. The hashtag #birdingwhileblack did not originate with this incident, but shined a light on the ways in which black and brown bodies are surveilled and controlled in the public sphere. Swift responses from Audubon NYC—where Christian Cooper was a board member—as well as Amy Cooper’s employer, revealed that these incidents will not go unseen or silently sanctioned. We are concerned that in the time of COVID-19, as more and more people are seeking use and refuge of parks and natural areas, we will have these encounters of friction and conflict. How will we as a society ensure equitable, safe, and open access for all to these vital natural resources?

Erika:

On 19 May I spoke with the administrator of a large park here in NYC. She wanted to talk with Lindsay and I about issues of race and inclusion and some research we had done in her park a few years ago. She had taken a diversity course from the Central Park Conservancy and was now reading a few academic papers on the subject. She worried that natural resource managers needed conceptual tools and training to address the issues that were coming up. It troubled her to know that certain people of color are not comfortable in their park and because of that, would not benefit from all that nature has to offer us, especially at this time. She told us how her community was severely impacted by COVID-19. She mentioned that many residents were trying to process the death of Ahmaud Arbery. And then came the May 25 incident in Central Park between a bird watcher and a dog walker. She knew that how the park is managed can contribute to inclusion (and exclusion) across differences of age, race, culture and creed. And she knew that this was a key part of her job. When we hung up, I sat there wondering if most people would believe that park administrators are ‘out there’ thinking and worrying about diversity, equity, and inclusion issues in deep and thoughtful ways? So often we might think of managing parkland as caring for trees and mowing the grass, but it is so much more. Such power and potential for transformation lies within our own capacity as green workers and through our public lands.

* * *

As we are writing this essay, which now feels poignantly dated-in-real time, our streets, sidewalks, and parks in New York City and across the country are erupting in protest over the murder of George Floyd. Our city and country are in anguish over these twinned crises of the pandemic and systemic racism. We know that the public realm has always been a space of assembly and discourse, including violent clashes and disagreements. Even in relatively quiet corners of the city, away from the protest, we see signs of solidarity, anger, and love. We read the landscape for these signs—handmade flyers, chalk drawings, and graffiti asserting that black lives matter—that echo the “shouts in the street”. We read these signs as they are barometers of social meaning and are important to the equitable stewardship of public space.

V. La longue duree

What can daily journaling, observing micro-practices and hyper-local geographic terrains tell us about la longue duree (“the long term” arc of history) and the way in which our society might fundamentally shift in response to this pandemic, as well as the way in which that pandemic intersects with our pre-existing inequities and vulnerabilities?

The historian Frank Snowden informs us in his most recent book on epidemics and societies that in addition to the loss of life, pandemics tend to cause painful rifts in our relationships to each other, among family members, friends, and social groups (Snowden 2019; see link). Over the long arc of time, things do eventually change. Snowden reminds us that the Paris School of Medicine emerged from the French Revolution with a turn toward observation and away from depending heavily on Hippocratic theory in managing public health. The motto of the 19th Century Paris School was: Peu lire et beaucoup voir (read little, but see a lot). In that seeing, it is important to consider what and whose narratives are told in the construction of a historic account. A recent article in the Nation posed this very question with respect to journalistic, archival, and historic coverage of this pandemic and the 1918 pandemic in Africa. How can we understand, document and grieve the grave loss of life and hold ourselves, our leaders, and our institutions accountable to change, but also see the creative, vital, sometimes improvisational, emergent adaptations by all of us, as agents that are critical to that change? These are also stories that need to be told—of lives lived with the pandemic—or else they will be forgotten and will not be learned from. We see this as a call to action for more voices to document and teach us from their lived experiences of the pandemic.

As humans and observers of the world, we journal; as researchers we can think critically about our observations. This approach has clarified the key questions and throughlines that we plan to consider in our own environmental stewardship and governance research in the New York City region and as part of a community of practice that includes researchers, natural resource managers, stewards, artists, and educators across a wide range of cities and towns. These include:

- How does the pandemic change our relationship with the city, nature, and public lands?

- How might we transform the public realm to better adapt to our new reality, in ways that are equitable, safe, supportive, and welcoming for all?

- How can our relationship with nature help us restore and strengthen our relations with each other at all scales: individual, group, and societal?

The compound disasters of the coronavirus, racial injustice, and climate change are shifting our relationships to the city and its public spaces. Who will be the transformative agents that can help address these issues? We have seen prior realignments of the way we conceptualize and orchestrate our cities and towns, with goals of achieving the sanitary city, the sustainable city, the resilient city. What does the post-pandemic city look like?

Lindsay K. Campbell, Erika Svendsen, Laura Landau, Michelle Johnson

New York

The findings and conclusions in this essay are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent any official USDA or U.S. Government determination or policy.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

about the writer

Laura Landau

Laura is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at CUNY Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, where she teaches U.S. Government and Environmental Politics. Her research focuses on post-disaster community organizing and the ability of grassroots movements to create local social and environmental transformation.

about the writer

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

Leave a Reply