Introduction

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

There has been a growing belief in the need for “equity” in how we build urban environments. The inequities have long been clear, but remain largely unsolved in environmental justice: both environmental “bads” (e.g. pollution) and “goods” (parks, food, ecosystem services of various kinds, livability) tend to be inequitably distributed. Such problems exist around the world, from New York to Mumbai, from Brussels to Rio de Janeiro to Lagos. Indeed, among many there is a sense that “equity” is not enough. Perhaps we need a more active expression of the social and environmental struggles that that underlie issues of equity and inequity in environmental justice and urban ecologies: one that is explicitly “anti-racist”, and which recognizes and tries to dismantle the systemic foundations of the inequities.

There is a logical resonance of this idea to a wide variety of identities, histories, prejudices, and processes that systematically exclude and discriminate among people, including (but sadly not limited to) colonialism, social caste, gender, sexual orientation, religion, ethnicity, and indigeneity.

So, let us try to imagine approaches beyond the mere basics of equity. What would an anti-racist (or de-colonial or anti-caste, and so on) approach to “urban ecologies” be? How would it be accomplished? Is it an approach that would create progress? How would it integrate social and ecological pattern and process? How would we as professionals and concerned urban residents engage with it?

These conversations must be about social issues as much as ecological ones. Light needs be shined in all directions.

We must be fiercely honest with ourselves by shining lights into the patterns and limitations — yes, the stubborn prejudices — of our own professions. What can we do as individuals? How can we nudge our disciplines — ecology, or planning, or architecture, or policymaking, or educations, or civil society, or whatever — in better directions?

And we must also move towards articulating what we are for and activate ourselves and our professions towards change that supports these things; not be satisfied with merely railing at what we are against.

What actions we will take to make cities that are truly better for everyone?

Banner image: Greenpop, Cape Town

Diana Wiesner Ceballos

about the writer

Diana Wiesner

Diana Wiesner is a landscape architect, proprietor of the firm Architecture and Landscape, and director of the non-profit foundation Cerros de Bogotá.

Nos preguntamos dónde y en cuántas calles de las urbes colombianas rendimos tributo a nuestros paisajes, a los pueblos originarios o a los indígenas? Nuestras plazas están repletas de monumentos de una España que arrasó con poblaciones y ecosistemas.

Sobre identidad y dualidad

Entender las realidades de la desigualdad de cada rincón de Colombia es difícil, desde la vida campesina del páramo de Sumapaz hasta las vivencias de los indígenas urbanos. Su comprensión se suscribe únicamente a lo poco que conocemos o a aquello que nos cuentan, en sus términos, los medios de comunicación. Hay una gran cantidad de matices para interpretarlas.

Lo que está sucediendo actualmente en Colombia representa un país encendido de dolores. Por una parte, indígenas y ciudadanos derriban monumentos como el de los fundadores de Bogotá y de Cali, que para ellos son símbolos del colonialismo. «Reivindican la memoria de sus ancestros asesinados y esclavizados por las élites. También [los desmontan] en señal de protesta por las amenazas que han recibido», dicen los medios. Lo que para los indígenas es un acto de dignidad, para otros es un hecho vandálico y violento. La estatua de Sebastián de Belalcázar, fundador de Cali, fue construida en el morro de Tulcán, sobre un cementerio precolombino.

Los expertos en la conservación del patrimonio cuestionan estas acciones pues este tiene que ver con una historia común, no con un momento reciente sino con uno precedente. Pero, a la vez, también lo reconocen como vehículo de narrativas incompletas que deben debatirse. Su representación no refleja la pluralidad de la vida y de la diversidad. Esto explica porqué la violencia contra símbolos culturales, ejercida por distintos sectores de la sociedad, ha sido recurrente en la historia de la humanidad.

Para algunos, derrumbar monumentos significa borrar huellas y argumentos que sirven para reinterpretar la historia. Estamos viviendo una nueva relación con estos elementos que llegan a reflejar ciertas identidades incompletas.

Nos preguntamos dónde y en cuántas calles de las urbes colombianas rendimos tributo a nuestros paisajes, a los pueblos originarios o a los indígenas. Nuestras plazas están repletas de monumentos de una España que arrasó con poblaciones y ecosistemas. Muchas personas proponen que la mayoría de estos monumentos deberían exhibirse en los museos, como parte de la historia. El debate está abierto.

En esta ruptura interpretativa de símbolos colonialistas nos cuestionamos también el hecho de haber borrado muchos de los trazados de asentamientos palatíficos y agrícolas de nuestros ancestros, posiblemente más ligados a la naturaleza. Un buen ejemplo de ello son los de la sociedad muisca en los camellones del río Bogotá.

¿Cuál es, entonces, la legítima representatividad? Si en lugar de las ordenanzas de las Indias —en las que el damero pasaba por encima de las geografías onduladas— las ciudades se hubieran estructurado desde las cuencas y desde la naturaleza, tal vez el resultado hubiesen sido trazados y ciudades orgánicas, con otras jerarquías y otros «desórdenes». ¿Acaso ese orden-desordenado o el nuevo orden que reclamamos —basado en soluciones que tienen como eje la naturaleza— será reflejo de sociedades más democráticas y equitativas o que quieren llegar a serlo?

Colombia es, en efecto, un conjunto superpuesto de estas dualidades: españoles-indígenas, naturaleza-no naturaleza, entre otras; sin embargo, lo más probable es que nos reconozcamos en una sola de esas miradas.

Decía Fernando Patiño, líder de la Fundación Ríos y Ciudades, que habría que «soñar con nuevos símbolos para este país tan golpeado por una violencia que ya tiene más años que nosotros, la generación de la mitad del siglo veinte». Y, en efecto, son los ríos, las montañas y los vestigios de humedales —madre viejas— los que deberían ser nuevos símbolos de unión, sin necesidad de levantarles un pedestal.

Bastaría con permanecer en profundo sentimiento de respeto y afecto al encuentro sagrado de las neblinas, las cordilleras y las aguas. El patrimonio de la vida. El respeto y el honor a todo aquello que lo representa, sin formalismos, debería ser la legítima representatividad de los territorios.

* * *

On identity and duality

Let us ask: where, and in how many streets of Colombian cities do we pay tribute to our landscapes, native peoples, or indigenous people? Our plazas are full of monuments to a Spain that razed populations and ecosystems.

It is difficult to understand the realities of inequality across Colombia, from the peasant life of the Sumapaz páramo to the experiences of urban indigenous people. Our understanding is limited to the little we know or what we are told by the media, in their terms. There are a lot of nuances that make interpretation difficult.

What is currently happening in Colombia represents a country ablaze with pain. On the one hand, indigenous people and citizens are tearing down monuments such as those of the founders of Bogota and Cali, which for them are symbols of colonialism. “By destroying the statues, they vindicate the memory of their ancestors murdered and enslaved by the elites. They also [dismantle them] as a sign of protest for the threats they have received,” say the media. What for the indigenous is an act of dignity, for others is an act of vandalism and violence. The statue of Sebastián de Belalcázar, founder of Cali, was built on the hill of Tulcán, on top of a pre-Columbian cementery.

Experts in heritage conservation question these actions because the statues reflect a common history; not a recent moment but a preceding one. But, at the same time, they also recognize the statues as vehicles for incomplete narratives that must be debated. Their representations do not reflect the plurality of life and diversity. This explains why violence against cultural symbols, exercised by different sectors of society, has been recurrent in human history.

For some, tearing down monuments means erasing traces and arguments that serve to misrepresent history. We are living a new relationship with these elements that come to reflect certain incomplete identities.

Let us ask: where, and in how many streets of Colombian cities, do we pay tribute to our landscapes, native peoples, or indigenous people. Our plazas are full of monuments to a Spain that razed populations and ecosystems. Many people propose that most of these monuments should be exhibited in museums, as part of history, not honored in city squares. The debate is open.

In this interpretative rupture of colonialist symbols, let us also recognize the fact that we have erased many of the palatial and agricultural settlements of our ancestors, which are closely linked to nature. A good example of this are settlements of the Muisca society on the banks of the Bogota River.

What is, then, the legitimate representation of people or territory? If instead of the ordinances of the Indies—in which the urban checkerboards reflected the undulating political and colonial geographies—the cities had been structured to reflect the indigenous origins and nature, perhaps the result would have been organic layouts and cities, with other hierarchies and different “disorders”. Will such disorderly order, or the new order that we demand based on solutions that have nature as their axis, be a reflection of more democratic and equitable societies, or societies that want to become more democratic and equitable?

Colombia is indeed an overlapping set of dualities: of Spanish and indigenous; of nature and non–nature among others. The probably is that we only recognize one side of these half’s.

Fernando Patiño, Rios y Ciudades Foundation chair, said that we should “dream of new symbols for this country so battered by a violence that is already older than us, the generation of the mid-twentieth century”. And, indeed, it is the rivers, the mountains, and the vestiges of wetlands—our ancient mothers—that should be new symbols of union, without the need to erect pedestals for them.

It would be enough to remain in a deep feeling of respect and affection for the sacred meeting of the mists, the mountain ranges, and the waters—the heritage of life. The respect and honor to everything that represents it, without formalisms, should be the legitimate representation of the territories.

Abdallah Tawfic

about the writer

Abdallah Tawfic

Abdallah is an architect, environmentalist and urban farmer. He works at the German International Cooperation (GIZ) and he is also the cofounder of Urban Greens Egypt, a startup aiming to promote the concept of Urban Agriculture in Cairo.

Women in public spaces

Women’s experiences and perceptions of public spaces differ from men’s and it is important to take these differences into account when planning and designing spaces. By applying an intersectional gender lens, women’s specific experiences, needs, and concerns can inform the development of safe and inclusive public spaces.

Public spaces play a significant role in community life. They provide a space for people to foster social connections, engage in physical activity, and provide access to green spaces. Being able to occupy public space can positively impact social, mental, and physical health. However, in many countries around the world — and more in the developing world — there is inequality in who can access and use these spaces comfortably and safely.

Evidence shows that women are more likely than men to feel unsafe in public spaces, and can also feel that the space is not designed with them in mind and consideration. This is particularly true for women who experience other intersecting forms of marginalization, such as those women from migrant backgrounds, older women, or religious orientation.

“Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” This was the way the writer and activist Jane Jacobs described how spaces of our cities can be thought of in her book Death and Life of American Cities (1961). A recent UN report stated that 99.3% of women are being harassed in public (see Note). This phenomenon has been explained in many researches as the natural result of the gender segregation within the society. A society with a culture of males perceiving public space as their own territory while females perceive it as a daily ambush.

Experiencing the public space as a safe space that encourages equal social interaction among users with diverse interests, opinions, and perspectives is a luxury that has not existed before in Egypt, and the society and different movements are exerting efforts nowadays to change it. When the revolution sparked in Cairo in 2011, women marched to Tahrir square with the hope of freedom, change in the political regime, and the rights for safe means of speaking their minds in public spaces.

The social classes of Egyptian women in the early 20th century were divided with different shares of the public sphere. This has somehow improved during time, however, although today there are still some unexplained stigmas around male-dominant public space activities, especially in informal areas. Coffee shops in informal settlements or “Ahwa” (short for coffee shop in Arabic) today remains a male-dominated space. There are no rules that prevent women from enjoying a cup of tea and chat with friends in any “Ahwa” in Egypt. However, the Egyptian society was raised with the idea that this space is not a place for women, and Ahwas are considered marked zones for men only to enjoy their drinks and play cards.

Women’s experiences and perceptions of public spaces differ to men and it is important to take these differences into account when planning and designing spaces. By applying an intersectional gender lens, women’s specific experiences, needs, and concerns can inform the development of safe and inclusive public spaces.

Good design is always the key to creating public spaces that are inclusive, accessible, and safe for everyone in the community. In order to create these spaces effectively, design must acknowledge and accommodate the specific needs and experiences of all groups within the community, taking into consideration the cultural traditions and activities that differs from a country to another, and break down retroactive activities that has turned into old fashioned rooted traditions that doesn’t make sense in our modern world.

Note:

- Braker, Bedour. (2018). Women in Egypt The myth of a safe public space. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327285947_Women_in_Egypt_The_myth_of_a_safe_public_space/citation/download

Jean-Marie Cishahayo

about the writer

Jean-Marie Cishahayo

Jean-Marie Cishahayo has around 20 years of studies and professional work in International development and lived in 4 continents: Asia, Europe, Africa, and North America. He has passion in capacity building in sustainable development, climate change, smart and green cities, local economic development, Resilient Monitoring and evaluation, Climate change. He is fluent in French, English, Chinese and Swahili.

Repenser “le droit à la ville” : le futur défi de la gestion de l’équité et de l’inclusion dans la matrice des systèmes naturels urbains

Les dimensions spatiales, sociales et économiques de l’inclusion urbaine sont étroitement liées et ont tendance à se renforcer mutuellement. Sur un chemin négatif, ces facteurs interagissent pour piéger les gens dans la pauvreté et la marginalisation. En sens inverse, ils peuvent sortir les gens de l’exclusion et améliorer leur vie.

Au-delà de l’équité urbaine, il est possible de construire l’antiracisme dans la gestion des systèmes naturels dans la matrice urbaine. C’est une approche qui pourrait créer des progrès, à mon avis. Voici quelques concepts et approches pour développer quelques réflexions.

Je voudrais commencer par recommander de faire revivre et de repenser l’idée originale du droit à la ville. Le “droit à la ville” est une idée et un slogan qui a été initialement proposé par Henri Lefevre dans son livre de 1968 : Le Droit à la Ville. Il a été acclamé plus récemment par des mouvements sociaux, des penseurs et plusieurs autorités locales progressistes comme un appel à l’action pour récupérer la ville et créer un espace de vie en contraste avec les effets croissants que la marchandisation et le capitalisme ont eu sur l’interaction sociale et l’augmentation des inégalités particulières dans les villes du monde entier au cours des derniers siècles (chapitres 2-17 de Writings on cities, sélectionnés, traduits et introduits par Eleonore Kofman et Elizabeth Lebas).

Le concept du droit à la ville de Lefevre ressemble à une combinaison de meilleures pratiques en matière de planification des environnements urbains avec pour objectif préliminaire de construire une communauté harmonieuse, de droits aux ressources urbaines, de l’équité en matière de justice environnementale, d’écologie urbaine, de l’antiracisme, de la haute qualité des services urbains tels que l’éducation, le logement, le transport, la sécurité, les services de santé, du partage des ressources environnementales naturelles et de la liberté de vivre dans une communauté d’écosystèmes humains. Ces droits sont appréciés passivement ; nous devons les préserver, les sécuriser, les maintenir et nous battre pour eux tout en respectant l’identité et les aspirations des autres. Cela nous rappelle aussi le concept d’”écologie urbaine”, une itération de l’approche de l’écologie humaine de l’École de Chicago, qui emprunte des concepts écologiques comme l’invasion et la succession pour tenter d’expliquer l’organisation de la société dans les villes (Andrew E.G.Jonas, Eugene Mc Cann et Mary Thomas, “Urban Geography”, 2015, Will Blackwell).

Au cours des siècles, je pense que ce concept a été un échec, ou un test fort pour les décideurs politiques, les urbanistes, les communautés et les individus. L’exclusion sociale, le racisme et la ségrégation ont commencé en l’absence manifeste d’un droit à la ville dans toutes les formes de vie et dans de nombreux pays du monde. Aujourd’hui encore, cela est politisé et institutionnalisé dans certains pays. Bien plus, il est préférable de comprendre comment ce concept de droit à la ville joue aujourd’hui dans les institutions, les pays et les communautés modernes. Voici des visions et des conclusions équilibrées de la Banque mondiale sur la création de communautés durables, inclusives et résilientes.

Aujourd’hui, plus de la moitié de la population mondiale vit dans des villes et cette proportion atteindra 70 % d’ici 2050. Pour s’assurer que les villes de demain offrent des opportunités et de meilleures conditions de vie à tous, il est essentiel de comprendre que le concept de ville inclusive implique un réseau complexe de multiples facteurs spatiaux, sociaux et économiques :

- Inclusion spatiale : l’inclusion urbaine exige de fournir des produits de première nécessité abordables tels que le logement, l’eau et l’assainissement. Le manque d’accès aux infrastructures et services essentiels est un combat quotidien pour de nombreux ménages défavorisés.

- Inclusion sociale : une ville inclusive doit garantir l’égalité des droits et la participation de tous, y compris des plus marginalisés. Récemment, le manque d’opportunités pour les pauvres urbains et la demande accrue de voix des exclus ont exacerbé les incidents de troubles sociaux dans les villes.

- Inclusion économique : créer des emplois et donner aux habitants des villes la possibilité de profiter des avantages de la croissance économique est une composante essentielle de l’inclusion urbaine globale.

Les dimensions spatiale, sociale et économique de l’inclusion urbaine sont étroitement liées et ont tendance à se renforcer mutuellement. Sur un chemin négatif, ces facteurs interagissent pour piéger les gens dans la pauvreté et la marginalisation. Dans le sens inverse, ils peuvent sortir les gens de l’exclusion et améliorer leur vie. Cela nous ramène à réfléchir à l’objectif des nouveaux Objectifs de développement durable. Personne ne doit être laissé de côté ; tout le monde compte. C’est un concept fondamental des droits de l’homme et de l’équité en milieu urbain. Parce que certaines de nos communautés ne sont pas plus inclusives, les mouvements de colère et d’antiracisme gagnent du terrain.

De millions de personnes souffrent de discrimination dans le monde du travail. Non seulement cela viole un droit humain des plus fondamentaux, mais cela a des conséquences sociales et économiques plus larges. La discrimination étouffe les opportunités, gaspille le talent humain nécessaire au progrès économique et accentue les tensions et les inégalités sociales. La lutte contre la discrimination est un élément essentiel de la promotion du travail décent, et le succès sur ce front se ressent bien au-delà du lieu de travail (ILO sur l’équité et la discrimination).

Il est possible de construire l’équité dans la matrice urbaine, mais cela nécessitera de repenser totalement notre politique urbaine, notre planification spéciale et nos systèmes éducatifs dans les écoles et dans les familles. Il faut se concentrer davantage sur des approches innovantes en vue de construire des communautés multiculturelles et inclusives dans un environnement équitable basé sur la nature. Personne ne doit être laissé de côté, si je peux emprunter ce slogan aux Objectifs de développement durable des Nations Unies.

Personne n’est née, raciste, extremiste, violente, exclusive, radicale. C’est dorénavent son type de famille, son type d’éducation, son type de compagnons, son type de communauté et son type d’environement politique qui ont transformé sa personalité et sa manière de penser. Alors quoi faire pour notre équité environemental? Et pourquoi nous sommes impuissants pour changer la done?

* * *

Rethinking “the right to city”: the future challenge in managing equity and inclusion in urban natural systems matrix

The spatial, social, and economic dimensions of urban inclusion are tightly intertwined and tend to reinforce each other. On a negative path, these factors interact to trap people into poverty and marginalization. Working in the opposite direction, they can lift people out of exclusion and improve lives.

Beyond urban equity, it is possible to build antiracism in managing natural systems in the urban matrix. This is an approach that could create progress in my view. Here, are some concepts and approached to develop some reflections.

I would like to start by recommending that we first revive and rethink the original idea of right to city. The “right to the city” is an idea and slogan that was originally proposed by Henri Lefevre in his 1968 book: Le Droit à la Ville. It has been acclaimed more recently by social movements, thinkers, and several progressive local authorities alike as a call to action to reclaim the city as to create a space for life detached from the growing effects that commodification and capitalism have had over social interaction and the rise of special inequalities in worldwide cities through the last centuries. (Chapters 2-17 from Writings on cities, selected, translated, and introduced by Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas)

Lefevre’s concept of the right to the city sounds like a combination of the best practices in urban settings planning with a preliminary aim to build harmonious community, rights to urban resources, equity in environment justice and urban ecology, antiracism, high quality of urban services such education, housing, transportation, safety, health services, sharing a natural based environment resources and freedom to live in a human ecosystem community. These rights are not granted; we need to preserve, secure, maintain, and fight for them while respecting other’s identity and aspirations. This reminds us also the concept of “Urban ecology”, an iteration of the Chicago School’s human ecology approach, borrows ecological concepts like invasion and succession in attempts to explain the organization of the society in cities. (Andrew E.G.Jonas, Eugene Mc Cann, and Mary Thomas, “Urban Geography”, 2015, Will Blackwell)

Over centuries, I think, this concept had been a failure or strong test to both policy makers, urban planners, communities, and individuals. Social exclusion, racism, and segregation started in the clear absence to right to city in all form of life in many countries of the world. Even today this is politicized and institutionalized in some countries.

Much more, it is better to understand how this concept of right to the city plays today in modern institutions, countries, and communities. The following are well-balanced visions and findings by the World Bank in order to build sustainable inclusive and resilient communities.

Today more than a half of the world population lives in cities and this proportion will reach 70% by 2050. To make sure that tomorrow’s cities provide opportunities and better living conditions for all, it is essential to understand that the concept of inclusive cities involves a complex web of multiple spatial, social, and economic factors:

- Spatial inclusion: urban inclusion requires providing affordable necessities such as housing, water, and sanitation. Lack of access to essential infrastructure and services is a daily struggle for many disadvantaged households.

- Social inclusion: an inclusive city needs to guarantee equal rights and participation of all, including the most marginalized. Recently, the lack of opportunities for the urban poor, and greater demand for voice from the socially excluded have exacerbated incidents of social upheaval in cities.

- Economic inclusion: creating jobs and giving urban residents the opportunity to enjoy the benefits of economic growth is a critical component of overall urban inclusion.

The spatial, social, and economic dimensions of urban inclusion are tightly intertwined and tend to reinforce each other. On a negative path, these factors interact to trap people into poverty and marginalization. Working in the opposite direction, they can lift people out of exclusion and improve lives.

This brings us back to reflect the purpose of the new Sustainable Development Goals. No one should be left behind, everyone counts. This is a fundamental concept of human rights and equity in urban settings. Because some of our communities are not more inclusive, anger and antiracism movements are gaining grounds.

It is possible to build equity in urban matrix, but it will require a total rethinking of our urban policy, special planning, and education systems in schools and families. It should focus more on innovative approaches to building a multicultural and inclusive communities in a nature-based environment. No one should be left behind, if I can borrow this slogan from the United Nations Sustainable development goals.

No one was born, racist, extremist, violent, exclusive, radical. It is indeed his type of family, his type of education, his type of companions, his type of community and his type of political environment that transformed his personality and his way of thinking. So, what can we do for our environmental equity? And why are we powerless to change the situation?

Cindy Thomashow

about the writer

Cindy Thomashow

Cynthia Thomashow was the Founding Director and is now the Academic Director of the graduate program in Urban Environmental Education at IslandWood and Antioch University Seattle. https://islandwood.org/graduate-programs/urban-environmental-education-maed-seattle

Natural systems are putty in the hands of city planners and the wealthy. Intentional inequities, more frequently than not, shape cities. UEE builds the leadership skills that support change-making focused on fairness, equity, and justice.

Antiracist thinking applied to the urban matrix means that we commit to making unbiased, equitable choices about the ways that water and air, roads and buildings, plants, and animals, as well as humans, are considered in city planning. It is not as simple as it may sound. The equitable management of natural systems in Seattle, for example, deeply intersects with its politics, cultural and class matrix, racial and ethnic make-up, economics, and entrepreneurial dreams.

Power belongs mostly to people who have money. Most often, those who are impacted the most, have little say in the matter. Unless you understand how the policies that govern growth are created, it is easy to become a victim of someone else’s desire. The disenfranchised are often not involved in decision-making unless advocates make it so. The graduate program I designed (Urban Environmental Education M.A.Ed. at Antioch University Seattle) prepares our students to understand and respond to these issues. Who benefits and who doesn’t from the impact of growth on natural systems? What species gain or lose a survival advantage? What humans benefit or are deprived of health and well-being? How do we learn to navigate the rights of all in fair and just ways?

Natural systems are as complex as they are necessary, which we forget sometimes in our hurry to develop places for the comfort of humans. It is amazing how natural systems and their inhabitants continue to adapt amid the chaos and change. Coyotes wandering the streets of cities at night. Racoons are in trashcans. Rats find new homes when buildings are razed. Plants taking refuge in the cracks of sidewalks. Water runs wherever a track can be found. So how do we to apply antiracist thinking to natural systems in the urban matrix?

I tried something different in my graduate class 10 years ago to better understand this complex dynamic. Students were challenged to think about the conservation of natural systems in urban places by radically shifting their perspective. I’ve used it since with great success. First, we walk the streets or the land with observational intention, making notes and maps and taking the time to know all of a place. We use a technique from On Looking by Horowitz, taking multiple routes through a neighborhood as an insect or animal, a young child or disabled adult. Students step aside from their human identity and represent another life-form or aspect of place: topography, air, water, soil. Students research how and why different species, habitats, people would be impacted by development. In the end, a trial is held. Each student testifies from the adopted perspective: trees, animals, water, soil, humans. The resulting designs for development are unique and inclusive. Taking the time to consider equitably how each vested interest will fare from the new structural development stimulates creative thinking and a unique plan for the future of each place.

If we listen carefully to community members about how the city manages natural systems, we often find that residents know clearly and deeply about the impact that policies have on the natural systems impacting their health and wellbeing as well as their access. They know from experience how natural systems have been altered, destroyed or improved. The impact of policies are revealed through their stories, their concerns and their perspectives. Green spaces in cities supposedly benefit everyone. Except that, green spaces often raise property values and become expensive, more exclusive, and less accessible to “everyone”. Following one of our ‘walks’ through the city, a student of mine noticed a subtle divide between public and private use of the garden space.

“I was here today with my Urbanizing Environmental Education class to examine the natural and social forces that shape contemporary Seattle. This walk around Belltown sparked a reading from the Urban Ecology class on the history of Seattle and the tensions between public and private that have plagued the city since its beginnings. Using this block as an example, known as the Cistern Steps, we walked a series of terraced plantings designed to clean rainwater as it travels through the city. These green terraced plantings echo the emerald rice fields of SE Asia. The steps are a haven of food and shelter for local wildlife. I was taken by the beauty and function until I noticed that they are “steps”. Meaning that anyone not able to walk or using wheels are banned. Here is a community-based project built on a public city block, that is not accessible to everyone. Plus, the sharp features embedded in the walkway by the expensive apartment dwellers abutting, made it impossible to sit or lay down. What is the line between public and private and who benefits in the end?” (Melani Baker, UEE 2016)

The Urban Environmental Education M.A.Ed. focuses on urban ecology through the lens of equity and inclusion, justice and leadership. We are out on the streets asking questions: Where and how is water directed through neighborhoods and why? What is the line between public space and private control…and who does each serve? Which neighborhoods are most impacted by air quality? How is stormwater runoff managed? Who benefits from tree canopy? How is wildlife managed? Where do the homeless find safe harbor?

The UEE approach deliberately integrates the study of systemic racism and the resulting policies and practices that govern the growth of cities. When the truth emerges, it becomes pretty clear who is in charge and who benefits from the decisions. Natural systems are putty in the hands of city planners and the wealthy. Intentional inequities, more frequently than not, shape cities. UEE builds the leadership skills that support change-making focused on fairness, equity, and justice. This means getting out into communities that are experiencing inequity and listening. It also means advocating for changes in the process of creating policies so that they are more inclusive. It means learning to use participatory action research so that everyone has a say and widely diverse perspectives are gathered. As Alicia Garza says in The Purpose of Power:

“Our wildly varying perspectives are not just a matter of aesthetic or philosophical or technological concern. They also influence our understanding of how change happens, for whom change is needed, acceptable methods of making change, and what kind of change is possible.”

— Alicia Garza, The Purpose of Power, One World, 2020, page 5

Charles Prempeh and Ibrahim Wallee

about the writer

Charles Prempeh

Charles Prempeh, PhD, is the Director of Research for African Christian-Muslim Interfaith International Council and holds a teaching appointment at the African University College of Communications, Accra, Ghana. He researches on religions, chieftaincy, politics, indigenous cosmological knowledge systems, and youth culture.

about the writer

Ibrahim Wallee

Ibrahim Wallee; is a development communicator, peacebuilding specialist, and environmental activist. He is the Executive Director of Center for Sustainable Livelihood and Development (CENSLiD), based in Accra, Ghana. He is a Co-Curator for Africa and Middle East Regions for The Nature of Cities Festivals.

Decolonizing African ecology to promote sound ecosystems

There is a complex inter-mesh of racism, socio-political, and economic injustice that accounts for environmental degradation in Africa, all with colonial origins. Lands in Africa became the property of Europeans, with Africans enduring all forms of brutality. It must now be de-colonized.

Historically, different philosophical dispositions have influenced how human beings have interacted with the environment. Until the birth of modern science, human beings in the pre-industrial world had been at the mercy of the natural environment. They subsisted based on the natural orientation of the environment. So, either through hunting or gathering, the environment was the determining factor in human existence where the so-called primitive human being had little knowledge about progress—in the sense of humans dominating the environment. The idea of progress is a modern concept that followed a long historical trajectory of the invention of modern agriculture and science.

With the invention of agriculture in 9000 BC, humans learned how to rule over the environment. But things came to a head when modern science was born in the seventeenth century, with humans gathering momentum in controlling the environment. This crystallised the era of the industrial revolution, beginning in the 1730s.

Since the eighteenth century, human beings entered the Anthropocene phase—as human activities began exerting a negative influence on the environment. But more central to the industrial revolution was the quest for material resources to feed growing industries in Europe. Prior to that, the need for human beings to work the large tracts of land in the Americas had resulted in the mass enslavement of Africans for about four centuries. The end of the slave trade was primarily a result of the Industrial Revolution—even though there were other secondary reasons, such as the advocates from humanitarian groups.

So, with the rise of the industrial revolution in the eighteenth century and the increasing need for raw materials, Europeans had to develop their own philosophical traditions to rationalise the wanton exploitation of distant lands, especially in Africa. Just as Europeans had used socially constructed theories—such as the Hamitic hypothesis—to justify the enslavement of Africans, alternative theories were developed to justify the destruction of the ecological system of countries in Africa. We are particularly interested in the Hamitic hypothesis because of two mutually inclusive reasons: First; it denies Africa’s contribution to human civilization, and which leads to the west questioning Africa’s contribution to solving contemporary challenges, particularly ecological injustice. We, therefore, argue that critiquing this theory would help us chart new pathways in ensuring that Africa shares an equal table with the rest of the world to stem the tide against ecological injustice.

Framed as “legitimate” trade, European colonising powers, including the British, French, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, and Germans had to integrate the philosophy of property into the arena of colonisation in the late eighteenth century. Indeed, prior to this century, the notion of a property had been hotly debated among early English philosophers, including Thomas Locke. Thomas Locke had argued that whatever nature offers is free and that it becomes an individual’s property if an individual applies his or her labour to it. This led to the idea of terra nullius—where nature was considered “no-man’s-land”. Terra nullius was philosophical ammunition that inspired Europeans to set off destroying distant lands to benefit the metropolitan countries.

The above elaborations point to the historical origin of racism and inequality in using the natural environment. Lands in Africa became the property of Europeans, with Africans enduring all forms of brutality, including German acts of genocide, against the Herero people in Tanzania in 1904. More recently, Africa continues to be the dumping ground for electronic toxic waste from western countries, including Germany. For example, Agbogbloshie, a neighbourhood of Accra, is one of the dumping sites of electronic waste from the West. Similarly, the Chinese since the 1980s have also been complicit in working with their Ghanaian counterparts to destroy the country’s water bodies through illegal mining, called Galamsey.

The above points to a complex inter-mesh of racism, socio-political, and economic injustice that accounts for environmental degradation in Africa. To address these issues, our paper explores how Africa and the world can work together to relieve the continent and the world from ecological injustice. Africa’s ecology needs to be decolonised. We argue that ecological decolonisation would be possible if Africans undertake the following steps: First, take pragmatic and strategic measures to minimise corruption within the environmental sector. Second, with Ghana, the country should engage all stakeholders, especially chiefs who are custodians of about 90% percent of land, to explore ways of overcoming ecological injustice. Third, countries in Africa should appeal to the international court to compel foreign countries and companies to stop destroying the ecology of Africa. Recently, in January 2021, Nigerian farmers in the Niger Delta won a court case against the Royal Dutch Shell company who were found culpable in oil pollution in Nigeria.

Isabelle Anguelovski, Anna Livia Brand, Malini Ranganathan, Derek Hyra

about the writer

Isabelle Michele Sophie Anguelovski

Isabelle Anguelovski is a Senior Researcher at the Institute for Environmental Science and Technology at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. She is a social scientist trained in urban and environmental planning and coordinator of the research line Cities and Environmental Justice.

about the writer

Anna Livia Brand

Anna Livia Brand iis Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture & Environmental Planning in the College of Environmental Design at UC Berkeley. Her research focuses on the historical development and contemporary planning and landscape design challenges in Black mecca neighborhoods in the American North and South.

about the writer

Malini Ranganathan

Malini Ranganathan is Associate Professor in the School of International Service at American University, An urban geographer by training, Dr. Ranganathan focuses on environmental injustices, what she calls “environmental unfreedoms,” in India and the U.S, and their structuring by caste, race, and class.

about the writer

Derek Hyra

Derek Hyra is Professor in the Department of Public Administration and Policy within the School of Public Affairs and Founding Director of the Metropolitan Policy Center at American University.

Decolonizing urban greening: From white supremacy to emancipatory planning for public green spaces

Decolonizing green city planning would involve prioritizing land recognition, redistribution, control, and reparations and developing new land arrangements as necessary to an environmentally just landscape.

Recent conversations around (in) justice in urban greening and public green space planning highlight the multiple dimensions of displacement, including housing loss (Dooling 2009, Gould and Lewis 2017) and social-cultural erasure that can affect socially marginalized groups. In addition to displacement linked to new real estate developments and increased housing prices, research in the field of green gentrification shows that municipal and private greening interventions can undermine residents’ sense of belonging in nature and their neighborhood and (re)produce erasure and trauma through socio-cultural and emotional loss (Anguelovski et al. 2020, Brand 2015).

As we argue in a recent article (Anguelovski et al. 2021), exclusion and dispossession can also materialize when urban greening overlooks racialized minorities’ experiences in what have been and are violent, discriminatory, and segregationist landscapes (Brown 2021, Finney 2014) and leave aside the ways in which racialized residents have been surveilled, criminalized, or coerced in public space (Ranganathan 2017). The murder of Armaud Arbery while jogging in 2020 in Georgia (USA) is only one illustration of this control and criminalization of Black bodies, as the Black Lives Matter movement and others call attention to.

Some scholars even go as far as arguing that urban greening is increasingly representative of the socio-spatial practices of white supremacism (Bonds and Inwood 2016, Pulido 2017) and settler colonialism, including land grabbing and frontier-driven value capture (Safransky 2014, 2016, Dillon 2014). In the United States, for example, previously forgotten Black landscapes in Dallas (West Dallas), New Orleans (Tremé), San Francisco (Hunters Point) and Washington, DC (Anacostia) have been shown to suddenly acquire value for planners and developers aiming to create new green ventures and build luxury homes in the vicinity of restored waterfronts, greenways, multi-purpose parks, and so-called resilient shorelines (Anguelovski et al. 2021).

Anacostia, in the Southeast section of Washington, DC, has long been an African American community. It was also a thriving business community before being impacted by urban renewal and public in the 1950s. Sixty years later, it is a new gentrification avenue, like much of Washington DC (Hyra and Prince 2015), much of it linked to new urban greening plans. In 2014, Anacostia received new attention when the New York City-based architecture firm OMA proposed its “avant-garde” plan for a $50-60 million green bridge – the 11th Street Bridge Park – which is expected to improve physical and social connections between the two sides of the Anacostia River while improving recreational and green spaces.

The 11th Street Bridge Park’s is certainly envisioned with social equity at the center. Anchored around the 2018 Equitable Development Plan (EDP) led by the nonprofit Building Bridges across the River, the project does include resident-centered workforce training and development and support to revive local business on the local Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue. Those efforts reflect the fact that new green assets can be strongly associated with resident-centered economic development and income generating ventures in order to achieve environmental justice for racialized minorities. The EDP also includes a Douglass Community Land Trust (CLT) and community-controlled housing and business development. The CLT uses, among others, the provisions of the city’s TOPA (Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act) and DOPA (District Opportunity to Purchase Act), legislations and builds partnerships with local lenders and nonprofit developers (i.e., MANNA and LISC) for down payment assistance.

However, in our views, the project overlooks the deep segregationist and exclusionary legacies of racial settlement, their ongoing manifestations, and risks of new white privilege. The broader developments and transformation that the project contributes to accelerate vulnerability to green gentrification and displacement, with new large-scale, high-end redevelopment projects such as Poplar Point and Reunion Square already banking on the value of the bridge park for future investments. As a developer told us, the bridge park project is a “first entry point. […] Our “goal [is to] go in early to emerging neighborhoods […] ready for redevelopment and to buy property and redevelop it and re-tenant it.” Furthermore, while the CLT model is planned to secure permanent affordable housing, its pace and implementation structure is unlikely to address the deep and growing intergenerational and interracial wealth gap, nor secure permanent affordable rental housing to enough working-class residents living in a fast-gentrifying neighborhood.

Much of the CLT is also financed by international finance groups such as Chase Bank likely attracted by the prospects of redevelopment and rebranding in Anacostia. In contrast, Black and workers-owned businesses and commercial ventures remain limited, thus further anchoring what some plantation economies in Anacostia. Last, even though the project uses cultural activities and artistic renderings to highlight the racial past of the neighborhood, it also illustrates how enduring racialized economic inequalities allow a certain type of greening and sustainability to be deployed, activating “cool” and “fun spaces, while risking invisibilizing and excluding dissonant or informal greening and land uses, as a resident shared with us: ““I will be good enough to serve you slurpies and hotdogs at the river festival, but not to live there.” In that greening, more emancipatory proposals such as land reparations to address a legacy of extraction and loss also remain under-discussed.

Our research thus illustrates is that the current development of 11th Street Bridge Park reinforces the false binary of urban greening (and eventual displacement) versus historic (and current) underinvestment while leaving green reparative justice limited. In contrast, decolonizing Green City planning would involve prioritizing land recognition, redistribution, control, and reparations and developing new land arrangements as necessary to an environmentally just landscape. It would also first mean to engage with the history of a multi-layered geography of dispossession and exclusion and include new cultural and symbolic recognitions of networks of resilience and care. It would allow for new institutional arrangements and the construction of alternative political power inspired in Black radical traditions. All in all, an anti-racist greening practice in the US and beyond would enact justice in newly amplified and life-affirming, emancipatory geographies for racialized groups.

References:

Anguelovski, I., A. L. Brand, J. JT Connolly, E. Corbera, P. Kotsila, J. Steil, M. Garcia Lamarca, M. Triguero-Mas, H. Cole, F. Baró, Langemeyer J., C. Perez del Pulgar, G. Shokry, F. Sekulova, and L. Arguelles. 2020. “Expanding the boundaries of justice in urban greening scholarship: Towards an emancipatory, anti-subordination, intersectional, and relational approach.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers.

Anguelovski, I., A. L. Brand, M. Ranganathan, and D. Hyra. 2021. “Decolonizing the Green City: From environmental privilege to emancipatory green justice ” Environmental Justice.

Bonds, Anne, and Joshua Inwood. 2016. “Beyond white privilege: Geographies of white supremacy and settler colonialism.” Progress in Human Geography 40 (6):715-733.

Brand, Anna Livia. 2015. “The most Complete Street in the world: A dream deferred and coopted.” In Incomplete Streets: Processes, practices, and possibilities, edited by J. Agyeman and S. Zavetoski, 245-266. Routledge.

Brown, Lawrence T. 2021. The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America: JHU Press.

Checker, Melissa. 2011. “Wiped Out by the “Greenwave”: Environmental Gentrification and the Paradoxical Politics of Urban Sustainability.” City & Society 23 (2):210-229. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-744X.2011.01063.x.

Dillon, Lindsey. 2014. “Race, Waste, and Space: Brownfield Redevelopment and Environmental Justice at the Hunters Point Shipyard.” Antipode 46 (5):1205-1221. doi: 10.1111/anti.12009.

Dooling, Sarah. 2009. “Ecological Gentrification: A Research Agenda Exploring Justice in the City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33 (3):621-639.

Finney, Carolyn. 2014. Black faces, white spaces: Reimagining the relationship of African Americans to the great outdoors: UNC Press Books.

Gould, Kenneth A, and Tammy L Lewis. 2017. Green Gentrification: Urban Sustainability and the Struggle for Environmental Justice: Routledge.

Hyra, Derek, and Sabiyha Prince. 2015. Capital Dilemma: Growth and Inequality in Washington: Routledge.

Immergluck, Dan, and Tharunya Balan. 2018. “Sustainable for whom? Green urban development, environmental gentrification, and the Atlanta Beltline.” Urban Geography 39 (4):546-562.

Pearsall, Hamil. 2010. “From brown to green? Assessing social vulnerability to environmental gentrification in New York City.” Environment and Planning C 28 (5):872-886.

Pulido, Laura. 2017. “Geographies of race and ethnicity II: Environmental racism, racial capitalism and state-sanctioned violence.” Progress in Human Geography 41 (4):524-533.

Ranganathan, Malini. 2017. “The environment as freedom: A decolonial reimagining.” Social Science Research Council Items 13.

Safransky, Sara. 2014. “Greening the urban frontier: Race, property, and resettlement in Detroit.” Geoforum 56:237-248.

Safransky, Sara. 2016. “Rethinking Land Struggle in the Postindustrial City.” Antipode.

CJ Goulding

about the writer

CJ Goulding

CJ Goulding (he/him) (@goulding_jr) is a weaver, a facilitator, a community builder, an organizer, and a storyteller who invests in the growth of people, the growth of connection between people, and the growth of communities. In his career, he has trained, mentored and supported national networks of over 450 leaders who are changing systems and creating equitable access to nature in their communities. He believes in liberation for people of color that is not based on the context of White supremacy, and is committed to organizing and redistributing power and resources in order to achieve equity and justice.

Changing Urban Ecology Through Radical Imagination and Community Gardens

While we recognize what needs to be done, it will not be easy, and we will face pushback and resistance from those who would like to see things remain as they have been.

Imagine with me that we are building an urban community garden. Can you see the empty lot? Can you hear the sounds of the city and community around you? As you create that mental picture, hold the idea that this garden is synonymous with the environmental, outdoor, and urban ecology movements.

Our world and our society are built on our beliefs and imaginations. In the United States, there is a blind faith, an inherent trust in our policies/laws, our society, our representatives, our systems, that they are built to support the idea, built into the U.S. Constitution, of “all men being created equal”. When we examine the history of the empty lot, this garden, it tells us a different story, one where our country and movements have been planted in exclusionary soil.

The mainstream outdoor and environmental movements have roots in ideas that imagined the wilderness and nature to be pristine, serene, untouched, and untrammeled by human contamination. Some environmental leaders and ideas around those times also include an imagination that like wilderness and urban areas, people held different value and could be separated when considering the impacts of policies, resources, and living conditions.

In the past, the plants sprouting in this empty lot from those imaginary roots are the weeds of the removal of the Miwuk and Paiute people from Yosemite Valley, the mistreatment of farmworkers during the 1950s (which led Dolores Huerta to start the National Farmworkers Association), and events like a toxic smokestack being demolished in Little Village, Chicago in 2020 despite the blatant concerns for the health of the Black and Brown people in the surrounding community.

All this is rooted and planted in the imagination, the belief and mindset that the mistreatment of people, specifically communities of color, for the benefit of “wilderness” and for a privileged group of people is justified, that certain people are expendable. These are the sewage sludge, industrial residue, the pesticides in our garden. These are the factors we will have to acknowledge and overcome in order to grow life in this plot.

So, what is the solution? How do we grow a garden in contaminated soil?

First, we get specific in our awareness of the contaminants. Knowledge of soil health and potential contamination are keys to helping communities identify and correct problems so that a garden is safe and productive. The same applies to our movement.

To plant this community garden, to lead the movement forward in an anti-racist and equitable way, we have to lay bare the mental models that harm people and land. We have to call those contaminants in the soil out specifically to treat it and grow moving forward.

FSG’s Water of Systems Change refers to six implicit and explicit conditions of systems change that we must investigate in order to be able to change. They are: Structural (policies, practices, resource flows), relational (relationships and connections, power dynamics), and transformative at the core (mental models).

Once we understand the contaminants in our movement’s racist soil, we have to employ what adrienne maree brown calls a “radical imagination” that thinks generations ahead, outside of the habits that brought us to our current predicament. The colonial leaders who brought us here are not going to be the leaders who bring us forward. Instead, our imagination for this garden has to be based in what has worked before and what we imagine is possible. In that way, although we have started with contaminated soil, our future is positive, informed, inclusive, and hopeful.

This community garden will bring life to land that was poisoned. These relationships we build are raised beds, the community centered practices are soil amendments to stabilize the contaminants. We will address those contaminants (exclusionary and racist mindsets), remove and unlearn those habits, and replace them with clean soil. We will follow knowledge from Indigenous communities and communities of color like the use of phytotechnologies (plants that extract, degrade, contain, or immobilize contaminants in soil) in order to lead us forward.

While we recognize what needs to be done, it will not be easy, and we will face pushback and resistance from those who would like to see things remain as they have been. Keep making progress.

I asked you to imagine us building an urban community garden. Our radical imagination has given us the context to ground us and the awareness of how we can move forward equitably. Now let’s open our eyes and get to work.

Baixo Ribeiro

about the writer

Baixo Ribeiro

Baixo is President of the Choque Cultural gallery in São Paulo.

A história da resistência das populações indígenas no Brasil é uma história de luta para manter as suas terraspermanentemente assediadas por um capitalismo desmedido e financiado pela indústria global. Minérios, madeira, petróleo são os nossos piores inimigos e os consumidores do mundo todo são responsáveis.

Eu e minha mulher somos netos de indígenas, porém não sabemos muita coisa sobre esse passado. Conseguimos facilmente identificar muitas gerações dos nossos antepassados brancos, mas sobre os indígenas não temos informação nenhuma. Isso é causa do histórico de racismo muito agressivo contra os povos originários no Brasil. Nossos avós e seus antepassados sofreram verdadeiros extermínios e, no começo do Século XX era muito perigoso demonstrar a sua própria cultura. Os pais não queriam que os filhos sofressem como eles e passaram a mimetizar a cultura branca, mudaram seus nomes e apagaram seu passado. Isso aconteceu com uma grande parcela da população brasileira, mas eu não consigo precisar a porcentagem dos 200 milhões de habitantes que dividiram essa mesma história, até porque muitos brasileiros não se identificam com a culturas indígenas.

Os povos originários são autênticos e verdadeiros protetores das florestas, além de possuidores de tecnologias muito especiais para cuidar da natureza e curar muitos de seus males. Então, a proteção desses povos é, ao mesmo tempo, a proteção da natureza. A promoção da cultura dos povos indígenas é ao mesmo tempo a promoção de soluções para o planeta.

A história da resistência das populações indígenas no Brasil é uma história de luta para manter as suas terras permanentemente assediadas por um capitalismo desmedido e financiado pela indústria global. Minérios, madeira, petróleo são os nossos piores inimigos e os consumidores do mundo todo são responsáveis pelo sistema que gera o desequilíbrio que está levando Terra ao seu fim e da qual as terras protegidas pelos povos indígenas são as últimas fronteiras de florestas ainda inexploradas.

Além da terra, os povos indígenas lutam também pela manutenção das suas culturas e das suas línguas. Segundo a UNESCO, são 256 povos e culturas diferentes no Brasil e cerca de 180 línguas muitas em processo de extinção. Na América do Sul são 45 milhões de indígenas, 642 povos e 500 línguas. Segundo a CEPAL, o Brasil com apenas 900 mil indígenas, possui o maior número de comunidades (305), seguido por Colômbia (102), Peru (85), México (78) e Bolívia (39). Apesar dos números conterem alguma imprecisão, Nota-se claramente a vulnerabilidade dos povos indígenas brasileiros.

Em relação às terras indígenas, a atitude do Estado brasileiro tem sido a de lenta demarcação, mais oumenos respeitada dependendo dos governos do momento. No entanto, a força do capital é muito maior do que a do Estado e consegue enfrentar e envolver todos os governos em seus lobbies, o que resulta numapermanente ameaça de retrocessos apesar de alguns avanços. A situação atual é muito preocupante no Brasil, pela soma de fatores: um governo bastante agressivo em relação às terras indígenas e o agravamento da pandemia com a consequente mortalidade da população indígena, sabidamente mais suscetível aos vírus gripais.

Em relação à promoção das culturas indígenas, a população não-indígena tem se interessado mais ao longo das últimas décadas pelo conhecimento de algumas culturas dos povos originários, bem como tem-se pautado com mais frequência as culturas ancestrais. Mas é uma tímida tomada de consciência em relação à gravidade da situação em que essas culturas estão inseridas no Brasil. Por exemplo, inexiste ainda um projeto estratégico de engajamento da população no aprendizado das línguas indígenas pelos não-indígenas.

Enfim, apesar dessas considerações um pouco superficiais, pretendi com a minha participação nesse fórum, chamar atenção para a questão do racismo contra os povos originários no Brasil e sua ligação direta com modos de vida que destroem a natureza do nosso planeta.

* * *

The history of the resistance of the indigenous populations in Brazil is a history of struggle to protect their lands from being permanently besieged by aggressive capitalism and financed by global industry. Extraction of ores, wood, and oil are our worst enemies. Consumers around the world are directly responsible.

My wife and I are grandsons of indigenous Brazilians, but we don’t know much about this past. We can easily identify many generations of our white ancestors, but we have no information about our indigenous progenitors. This is because of the history of very aggressive racism against the original people in Brazil. Our grandparents and their relatives suffered real exterminations and, therefore, at the beginning of the 20th century it was very dangerous to demonstrate their own culture. Parents did not want their children to suffer like them and started to mimic white people’s culture, changed names, and deleted their past. This happens to a large portion of the Brazilian population, but I cannot specify the percentage of the 200 million inhabitants who share this same history, not least because many do not identify themselves with indigenous cultures.

The indigenous people are authentic and true protectors of the forests, in addition to possessing very special methods to take care of nature and cure many challenges. So, the protection of the indigenous peoples is, at the same time, the protection of nature. The promotion of indigenous people’s cultures is at the same time the promotion of solutions for the nature of the planet. The history of the resistance of the indigenous populations in Brazil is a history of struggle to protect their lands from being permanently besieged by aggressive capitalism and financed by global industry. Extraction of ores, wood, and oil are our worst enemies and consumers around the world are responsible for the system that generates the imbalance that is taking Earth to its end and of which the lands protected by the indigenous peoples are the last frontiers of unexplored forests.

In addition to the land, indigenous people also fight for the maintenance of their cultures and their languages. According to ONU (2014), there are 256 different indigenous groups in Brazil and about 180 languages, many of which are close to extinction. Only to compare, in South America there are 45 million indigenous people, 642 indigenous groups, and 500 languages. According to CEPAL (2010), Brazil has only 900,000 indigenous, but has the largest number of indigenous communities (305), followed by Colombia (102), Peru (85), Mexico (78) and Bolivia (39). Although the numbers contain some inaccuracy, the vulnerability of Brazilian indigenous peoples is clearly noted.

In relation to indigenous lands, the attitude of the Brazilian State has been one of slow demarcation, more or less respected depending on the governments of the moment. However, the strength of capital is much greater than that of the state and is able to face and involve all governments in their lobbies, which results in a permanent threat of setbacks despite some advances. The current situation is very worrying in Brazil, due to the sum of factors: a very aggressive government in relation to indigenous lands and the worsening of the pandemic with the consequent mortality of the indigenous population, known to be more susceptible to influenza viruses.

In relation to the promotion of indigenous cultures, the non-indigenous population (the majority of the Brazilian population is mixed between white, black, and indigenous peoples) has been more interested over the last decades in the knowledge of some cultures of the original native peoples, as well as the ancestral cultures. But it is a timid awareness of the seriousness of the situation to which these cultures are subjected in Brazil. For example, there is still no strategic project to engage the population in the learning of indigenous languages by non-indigenous.

These are just brief observations, but with my participation in this forum I intended to draw attention to the issue of racism against the indigenous peoples in Brazil and their direct connection with ways of life that destroy the nature of our planet.

Suné Stassen

about the writer

Suné Stassen

Suné is the co-founder, custodian and CEO of Open Design Afrika, a social enterprise and not for profit company. She is a designer, impact entrepreneur, design activist and educator who strongly believes in the power of creativity as a change agent and catalyst to drive and scale systemic change, and to develop a future-making culture who can confidently add value to the greater good, drive the UN SDG’s agenda and contribute to the design of regenerative economies, thriving communities and flourishing environments.

Designing thriving urban ecologies for 10,000 generations and more

We at Open Design Afrika believe that collaborative Creative Intelligence is a SUPER POWER! We also believe that every child and citizen should have the right to develop it and be empowered to confidently contribute to the future-making of a world we can ALL feel proud to live, work and play in.

As a designer I always look at our manmade world through a design lens with the human race at the helm as the chief designer. For generations we have successfully engineered a very destructive and unjust world for living in.

The current Global Pandemic sharply heightened our awareness of thriving inequalities and how everything in this world is connected “from the sunflower to the sunfish”, as boldly expressed by Richard Williams also known as Prince EA”, a spoken word artist and civil rights activist, in his epic video titled “Man vs Earth”, a highly recommended video that cuts to the bone, puts things into perspective and breaks down complexities into basic building blocks, vital to ignite, escalate and sustain real systemic change.

Humanity’s inability to systemically approach the design of our manmade world, has captured and disabled global populations from prospering and confidently contributing as future makers.

The triple bottom line— People, Planet, and the Economy—forms the foundation of this design process. Disregarding people and planet had a devastating ripple effect felt by generations. This resulted into a serious disconnect across all levels of society, in business, government and in our environments. History has proven that without a holistic and systemic approach it is not possible to create a conducive environment where ecologies can flourish and a prosperous value chain can be developed that is beneficial to all. At best, the legacy of the human race has been a world that is in constant survival mode,

Today far too many show the scars of the unjust global culture we have engineered, but as an intelligent species I strongly believe that we are equally capable of designing the exact opposite if change is driven through wisdom instead.

Observations

Why do we continue to reinvent the wheel with solutions less impactful and sustainable? As the top designer of ecologies, Nature boasts with the most impressive portfolio of successful models, processes, and systems that stretch across 3,8 billion years which allows all living organisms no matter their size, to flourish. It will be very wise to learn from Nature and implement these learnings across education, in society and across all other sectors. We must learn from nature how to approach our manmade world as a holistic design challenge and aim to develop strategies that will impact and allow humanity to thrive for 10,000 generations and more – THE SAME WAY NATURE DOES. This I believe is the greatest legacy worth aspiring too.

Education shapes the fabric of society and to date it has been a significant contributor to inequalities. The education we have experienced across generations did not optimize participation and the opportunity for ALL children to develop their full potential. It certainly did not enable society with FUTURE-MAKING LIFE SKILLS. Developing Creative Intelligence through creativity, phenomenon-based learning, play, AND STEAM education democratises participation and optimise the learning experience and the development of crucial future-making skills in ALL CHILDREN and across all levels of society. This I believe will be a great start to address the skill shortage of the past, and shape the foundation to start transforming society into a more prosperous world that’s beneficial to all.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution suggests unique and exciting opportunities for large-scale transformation to achieve and uphold the UN SDG’s. Yet a symbiotic relationship between man and machine is crucial to succeed. Priority investment in technology and tech skills without EQUAL investment in Creative Intelligence, is not driving and serving this agenda. This includes future-making skills like empathy, creativity, emotional intelligence, critical thinking, complex problem solving, judgement, decision making and collaboration that defines and differentiate us from the machine – it’s our ONLY competitive advantage. Other investments will proof to be short-lived without investing in appropriate social and human capital that can uphold, maintain, and drive future prosperity.

Albert Einstein once said: “Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited but Imagination encircles the world” and I could not agree more.

Imagine the immense added value and ripple effect on our future economies, environments, and communities if Empathy and Emotional Intelligence guided all our decisions, in government, as leaders, and in civil society. Creative Intelligence will develop the human qualities and social capital that’s needed to drive and build the just and equitable society we should strive to design.

At Open Design Afrika we believe that collaborative Creative Intelligence is a SUPER POWER! We also believe that every child and citizen should have the right to develop it and be empowered to confidently contribute to the future-making of a world we can ALL feel proud to live, work, and play in.

Watch Open Design Afrika’s message to the world:

Laura Landau

about the writer

Laura Landau

Laura is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at CUNY Kingsborough Community College in Brooklyn, where she teaches U.S. Government and Environmental Politics. Her research focuses on post-disaster community organizing and the ability of grassroots movements to create local social and environmental transformation.

Real transformation only happens when we examine issues of ownership and control in order to radically redistribute power. The good news is that many environmental groups are already showing us how to take these steps.

Thanks to the work of environmental justice scholars and activists, we have long understood that the placement, quality, and safety of environmental resources are shaped by structural racism. This is often discussed in terms of distributional justice, or the equal distribution and maintenance of green and blue spaces. During COVID-19 in the United States, we saw first-hand how access to open space, the safest place to spend time in public during the pandemic, is inequitably distributed. Further, the events of summer 2020—from the racialized police call on Christian Cooper to George Floyd’s murder—reminded us that even in public spaces, non-white bodies are not granted equal safety and freedom. These instances go beyond distributional justice to issues of procedural justice and interactional justice, which get at the inequitable decision-making processes and inclusivity within green and blue spaces.

In order to work against the injustices that are so deeply embedded in our society, we have to acknowledge the ways in which our histories of colonization and slavery continue to shape our urban environments. This work begins with being explicitly anti-racist in our missions and actions. This includes speaking up and sharing statements in response to racist violence, conducting anti-bias trainings for staff, board members, and volunteers, taking a look at who is represented (and who is absent) in each of these roles and at all levels of the organization, and initiating dialogues to gather input on what needs to change.

But the work does not end there. Real transformation only happens when we examine issues of ownership and control in order to radically redistribute power. The good news is that many environmental groups are already showing us how to take these steps.

In the summer of 2020, along with my colleagues at the USDA Forest Service and the NYC Urban Field Station, I interviewed representatives from 34 civic environmental stewardship groups in New York City. These groups range from small informal neighborhood groups to citywide organizations, yet they share an intention to steward the local environment through land management, conservation, scientific monitoring, systems transformation, education, or advocacy. I found that stewards are already participating in anti-racism work in a wide variety of ways—some just beginning to examine their relationships to environmental justice, but others thinking deeply and creatively about how to use their power and resources. For example, one steward shared her vision to connect and partner with an Indigenous community group and offer them ownership of a garden plot as a gesture to the LANDBACK movement. In addition to allowing Indigenous stewardship of the land, this partnership could become a powerful education tool for the many school groups that come through the garden. Imagine if all of our conversations about environmental equity started from a place of acknowledging that the land we manage is stolen land. How might that change the way we think about environmental justice?

Another group that stewards a neighborhood park was able to leverage their power to support protesters following the police murder of George Floyd. When they noticed that NYPD vehicles were surrounding the park during peaceful protests, they stepped in to communicate on behalf of the organizers and requested that no more police vans be sent. This seemingly simple step limited potentially violent action by police against protesters, and affirmed to the community that the park is a place where they should feel safe and protected.

Finally, a number of stewardship groups led by women of color discussed the steps they are taking to gain ownership of their local food systems. They shared that food sovereignty and control of the food chain are essential to promoting the health and economic wellbeing of their communities. Efforts such as starting locally owned food co-ops and sliding scaled produce boxes have the potential to become long-term and sustainable interventions to address chronic issues like food apartheid. These shifts do not happen overnight, but they are nonetheless crucial seeds of change. If we learn from and support the efforts of groups like these, I trust that we will begin to see more new and creative projects that deepen the possibilities for anti-racist natural systems management.

María Méjia

about the writer

María Mejía

My heart is scattered across Colombia, Germany, the United States. and the Philippines. I have worked with incredible teams (Asian Development Bank, German Cooperation Agency, PIK Institute, etc.). Now back home, I’m currently leading the BiodiverCities by 2030 Initiative at the Humboldt Institute of Colombia. Editor of Urban Nature: Platform of Experiences (2016) and Transforming Cities with Biodiversity (2022). Volunteer at Fundación Cerros de Bogotá. Friend of TNOC since 2013.

Live now! Claiming back the right to the city: A tale from Colombia’s streets

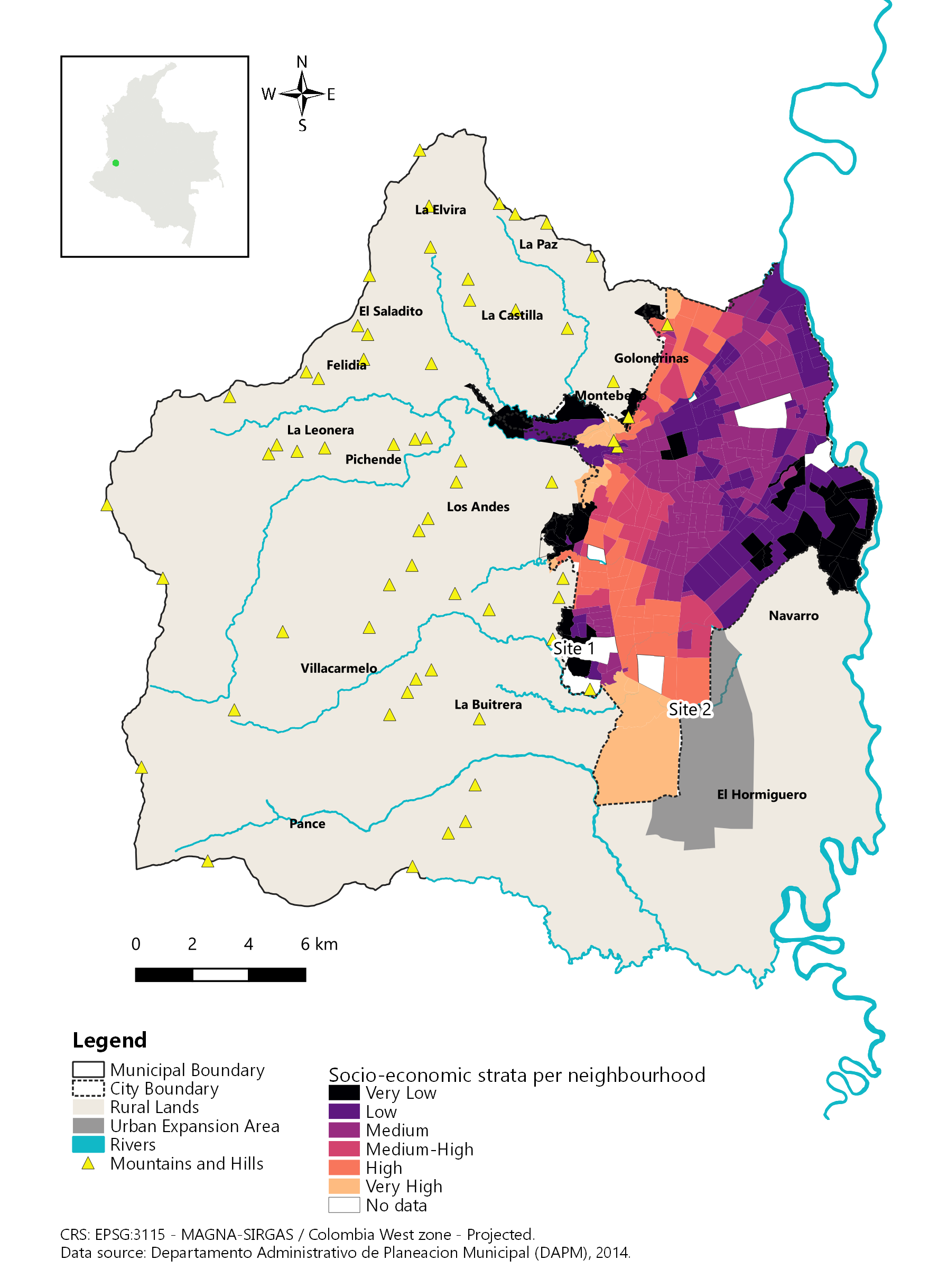

Cali’s urban natures mirror deep wounds of racism and colonialism. Its urban development in the 20th Century was embedded in historical dynamics of labor exploitation and the trade of goods and commodities. The historical concentration of land by elites made of Cali a highly segregated city: it was a radicalization of space.