There is not one magic framework that will tell the true story of community gardens, but it is crucial that we pay attention to the profound work occurring in community-managed garden spaces, and tell the story that does these efforts justice.

A team of practitioners and researchers at the Central Park Conservancy Institute for Urban Parks, NeighborSpace, Borderless, and USDA Forest Service – Northern Research Station met from September to November 2021 to discuss research on social infrastructure and urban green spaces, with the goal of translating academic literature into practical knowledge that can support nonprofits, community gardeners, foundations, and policymakers. Our aim is to better communicate the value of community-managed spaces and their stewards as critical social infrastructure. Starting from the synthesis of the literature and a case study of community gardens, we created a framework for diagramming visible and invisible systems that produce known benefits and outcomes that could be applied to multiple community-managed spaces.

Social infrastructure and stewardship

Social infrastructure is defined as “the physical places and organizations that shape the way people interact with each other in everyday life” (Klinenberg 2018, p. 5). We recognize that these are both physical spaces―such as parks, libraries, coffee shops, and sidewalks―as well as virtual spaces and social processes. In this essay, we turn our focus on less-visible social dynamics of how neighborhood leaders and stewardship groups operate because we think these dynamics and networks are critical in shaping community spaces but require better understanding.

This essay is part one of a two-part series, click here to read part two.

We define stewardship broadly as any act of caring for the local environment and it often occurs through these six types of actions or functions: conservation, management, education, monitoring, advocacy, and transformation (Svendsen & Campbell 2008; Fisher et al. 2012; Connolly et al. 2013). It involves hands-on work such as digging in the dirt and planting trees, but also community organizing. Stewardship is distinct from land ownership. Anyone can be a steward, including civic groups without formal jurisdiction over a site. Research has found that civic stewardship groups activate green space to function as social infrastructure in a range of important ways. Stewards foster friendships, associations, and social cohesion. They create gathering spaces and enliven them with place-based and culturally relevant programming and engage in community organizing and planning (Campbell et al. 2021).

Community stewardship is not without tensions, challenges, and conflicts. In fact, mediating differences among community garden members has been identified by gardeners as one of the critical ways that they learn conflict resolution and strengthen democratic practice (Campbell et al. 2021). Further interrogating the power dynamics and decision-making processes that enable or constrain constructive conflict resolution is crucial to understanding the social function of civic groups.

Stewardship practices are critical building blocks for strengthening community capacity and well-being and fostering social resilience. If you better know and trust your neighbors, and can come together to organize and solve problems, you are better poised to adapt to future events. Indeed, decades of research has demonstrated the ways in which stewards often work in the context of disturbance and recovery cycles. Whether the disruption is slow-moving presses or fast-moving pulse events, stewards both prepare for and respond to disruptions caused by climate change, tornadoes, hurricanes, and pest invasions. And they also respond to social and political upheaval, such as the September 11, 2001 terrorist event, as well as chronic disinvestment, economic decline, and social and racial injustice (Campbell et al. 2019).

Stewards work to restore landscapes, enhance livelihoods, and support communities through acts of caretaking and claims-making. Research has found that stewardship can strengthen social resilience through fostering: place attachment, collective identity, social cohesion, social networks, and knowledge exchange (McMillen et al. 2016). Most recently, scholars have been examining stewardship during the COVID-19 pandemic, and we have found that stewardship groups exhibited learning and flexibility during the pandemic. Groups learned from previous disturbances (e.g., Superstorm Sandy) and adapted to COVID-19 and uprisings for racial justice (Landau et al. 2021). Clearly, stewardship groups are displaying an incredible amount of adaptive capacity and are a critical part of our social infrastructure that shapes the functions and meanings of our public realm.

Describing a framework for social Infrastructure visibility

Providing updated narratives about the real work of what it takes to “community manage” a space is part of our shared stewardship work. It is not only garden leaders who need a richer reflection on how community gardens function as social infrastructure. The general public, policymakers, and funders would be more powerful advocates if a more complete picture of community gardens was made more legible.

It was with this challenge in mind that NeighborSpace, as part of the Central Park’s Conservancy’s Partnership Lab, convened a working group, brainstormed, and discussed both content from selected literature and specific examples of NeighborSpace community-managed gardens. Out of these discussions emerged a design challenge to identify and organize key concepts in a way that integrated, analyzed, and visualized dimensions of social infrastructure happening in community-managed space. The first step was to identify a thematic structure that could serve as an umbrella for multiple layers and multiple gardens.

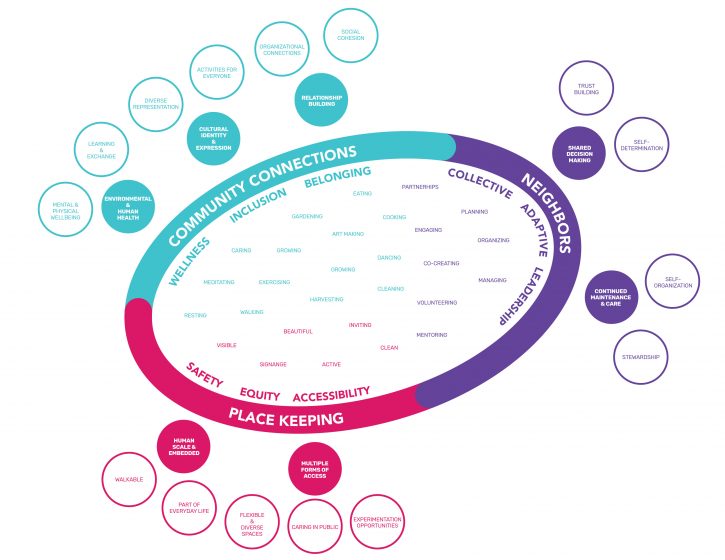

The framework that emerged focused on three connected themes:

- Neighbors: This theme relates to organizational aspects of the community ― the core and consistent caretakers, and the community leaders who are “behind the scenes” organizing people (volunteers), building relationships with the broader community (partnerships), planning both the physical space and activities (maintenance and programming), and identifying resources to support the garden activities.

- Place-keeping: This is often the theme that generally has more visibility ― how the space is protected and held for the neighborhood, how the physical features of the space reflect the values and aesthetics of the community of caretakers and stewards. This also refers to the spatial typology (e.g., small-scale gardens that are embedded in the neighborhood fabric), and their accessibility and communication system (signage and other “signs of care”).

- Community connections: This theme refers to the network of relationships and support(ers) that neighbors from community-managed spaces seek to develop to engage their community assets and resources. The stronger the network and the capacity for collaboration with other community groups, organizations, and initiatives, the more community gardens create a sense of belonging and inclusion.

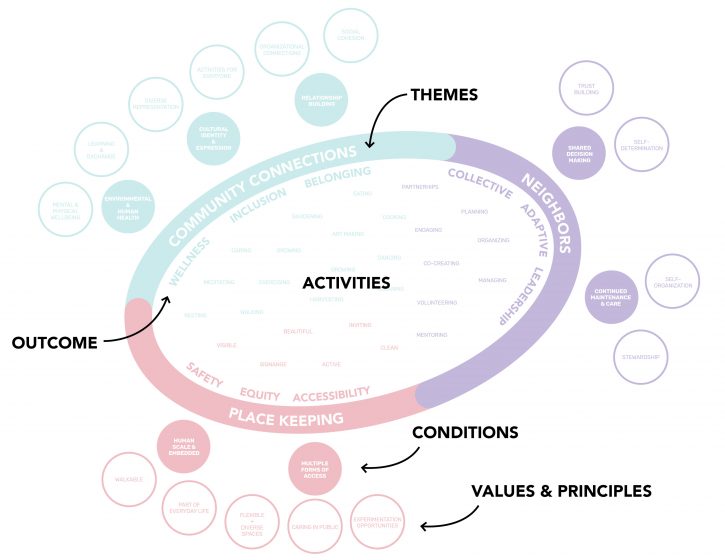

These themes led us to map the existing activities and the conditions supporting the activities and to define the values, principles, and outcomes that are supportive of community-managed spaces, particularly community gardens. The guiding questions for these layers, from inside the circle to out, are:

- Activities: What diversity and range of activities occur in these spaces?

- Conditions: What enables these activities to happen?

- Values and Principles: What guides how or why activities happen?

- Outcomes: What is the impact or the benefit of these activities and conditions guided by values and principles?

These themes and layers provided the template to compose statements describing the relationship between these elements. Below is an example organized by the aforementioned themes:

- Neighbors come together to make informal decisions. This leads to a slow steady trust building. The informal decision-making is the condition that enables trust building as a principle; these influence, for instance, how planning, engaging, and/or organizing activities happen.

- Neighbors care in public in multiple creative ways. Signage and art by neighbors create a sense of place. Caring in public is a condition of place-keeping that enables creating a sense of place as a principle; these influence, for instance, how beautification and cleaning activities happen.

- Neighbors activate the garden through yoga, music, dance, and art. These activities build a recognized and accessible community venue. Diversity of activities is a condition of community connections that enables community gardens as community venues; these influence, for instance, how artmaking or exercising activities happen.

An important goal of our framework is to create a consistent narrative and visual language for specific gardens to share with multiple audiences, including stakeholders, foundations, media, government, and their own garden community to advocate for policies that support investment in community-managed space stewardship. This framework offers a step toward more comprehensively mapping and expanding the public visibility of community care.

To download a toolkit summarizing this framework for community conversations, click here: http://neighbor-space.org/caring-in-public-revealing-community-gardens-as-social-infrastructure/

Two versions of visualizations are available, a pamphlet prepared for a more concise explanation of community gardens as social infrastructure, as well as a deeper dive, prepared from the slide presentation presented at The Nature of Cities March 2022 conference, in collaboration with the authors of this paper.

Community care in community-managed open space: NeighborSpace in history and process

This framework was informed, inspired, and framed by the work of NeighborSpace, a 25-year-old urban land trust in Chicago and an umbrella organization for more than 130 open-space neighborhood projects across the city. NeighborSpace supports community leaders in their effort to bring together neighbors to activate, transform, and protect empty lots and underutilized open space. NeighborSpace, since its founding, has been an anchor for land protection and a unique national urban land trust model; its mission-driven long-term protection and constancy provides an important vantage point for observing changing stewardship models. The community projects that NeighborSpace helps support are community-managed, grassroot efforts that bring together collaboration among neighbors and local community groups and are predominantly mobilized and maintained by volunteers.

At the founding of NeighborSpace in 1996, NeighborSpace’s structure existed under two basic buckets― land acquisition and land monitoring, playing a minimal role in leadership development, fundraising, and programming. In the last ten years, however, garden groups have asked more urgently for navigation and training in these latter areas. This is a marked difference from the first decade of NeighborSpace; the mid 1990’s reflected a period in which several Chicago nonprofits prioritized community gardens, providing now non-existent financial support, programming, and maintenance. This emerging request for guidance also, perhaps, reflects that many who step into community garden leadership today have less experience with “third space” places -churches, social clubs, and other informal associations that engage in regular group decision-making. Additionally, group decision-making as a public practice of equity (or not, as often is the case) is something that many community-engaged leaders want to get better at in a thoughtful, accountable way.

In 2012, NeighborSpace’s organizational chart replaced “land monitoring” with “stewardship”, to more intentionally and organizationally “steward the stewards.” As part of this shift, NeighborSpace regularly surveys garden leaders about their garden’s “community health.” The responses are both broad and specific, and include requests for online fundraising tools, training in facilitating, decision-making and conflict resolution, opportunities to socialize with other garden leaders, favorite tools for the tool library (including video projectors and outdoor projection screens, ice cream makers, fire pits), and access to porta-potties. The most pressing requests from gardens groups are not what one might immediately think (how to yield more vegetables, for example); again and again, groups ask for better skills at navigating the way a community works together- how to successfully engage with governmental organizations, community groups, alderman, private businesses, neighbors, and other community gardeners.

In the surveys, garden leaders also share frustrations. They consistently observe that much of the general public does not understand how community management functions. Uninvolved neighbors, they report, tend to think garden leaders are getting paid, feel uninvited to the garden, and sometimes think the public effort of community gardens looks messy. Additionally, new gardeners who enter the gardening group are surprised by the tensions among the group. And, as it relates to this essay particularly, the leaders themselves often feel, because there are so few examples of community-managed processes, (i.e., the “warts and all” of public care) that they personally might be doing something wrong.

Sharing a more complete story, internal and external, of community-managed spaces

A key place to start a more complete story of community care is to investigate the pre-existing narratives and public perceptions of community gardens. The popular novella Seed Folks, for example, sets the traditional stage of what comes to mind when thinking of a community’s best self; a shared garden gives people from different races, socioeconomic statuses, skill levels, and ages the opportunity to share in work, grow food and conversation, and understand each other better. Each character gets an equal opportunity and a full chapter to share their story, and the vegetables and flowers are an idyllic background for the group photo at the end of the book.

In real life, the aspiration of community cohesion is an honorable and urgent thing; people do want opportunities to come together for group work in shared spaces, to be connected, to do a thing, and, yes, to take good pictures; and it can’t be denied, community gardens at the end of a workday are very photogenic. But community care is messier, more complicated, and shows up in many more ways than vegetables and flowers. Leaders spend time picking up litter from their parkway, practicing decision-making rules, hosting classes, counseling new gardeners, writing grants, building accessible spaces, negotiating with aldermen, coordinating local partners for events, and fixing fences, both literally and figuratively, between neighbors and each other. Community care is all of that, and future garden leaders are in a better position to “keep on caring” through the hard parts if the work they are doing is reflected back to them in affirming ways.

To “keep on caring”, community gardens need to feel seen; the visual framework of community gardens as social infrastructure creates a shared place to build and say, “that’s us!” to not only gardeners themselves, but to funders, government entities, and policymakers. Funders often don’t fully understand truly what community gardens set the conditions for, undervaluing some things (community and neighbor connection, stormwater management, participatory decision-making), and overvaluing others (vegetable output). Policymakers and municipal departments, often brought together for collaborative open space projects that engage water, land, and asset departments could use these intersections to create productive dialogues that don’t often happen between city services. A truer understanding of how community-managed spaces function, for example, could mitigate enforcement of weed fines, feed funding back into the very community caring for these green spaces, and create relationships between residents and sanitation departments, all while offering a truer picture to all parties of what it means for a city to work together.

NeighborSpace has taken steps to address some of these issues of legibility quite practically. For the public, transparent processes, continued engagement, and clear invitation are key. For the garden leaders, continued check-ins, dialogues, and leadership training on decision-making and public programming are vital for leadership growth. For city leaders and funders, when doing site visits, opportunities to speak and see communities at work (not just the garden spaces themselves) are essential. In all cases, recognizing prior beliefs about community gardens is an important place to start. NeighborSpace sometimes tells new garden leaders, “You have to host harder than you think,” and that applies to NeighborSpace in its role as well. Community gardens are not well understood, so we have to keep explaining them harder than we think.

The public face of community gardens and the gap between what is happening and how it is being perceived needs attending to, and the framework provides opportunities for that. On the micro-level, this condition requires thoughtfulness on how the general public is invited in to participate, for example, and entails simple but often overlooked things like more explicit visitor-centered invitations on workdays (for example, signs in large font that say, “Talk to the person in the orange vest to get involved!”) On the macro-level, there is need for a national interrogation of why some people are involved more than others (who and how neighbors feel invited or available often reveals structural inequities that are reflected in the larger culture, but not talked about explicitly in community gardening), and how those with more time (and often more resources) inherit decision-making.

Creating visible opportunities for the general people to care for space simply by enjoying it with their family is an emerging model that makes community-managed space more available for those with less free time. Nature play and conservation trail gardens, with inviting language, where the primary activity allows for children to play in nature, and allows families with less free time to learn, enjoy nature, and maybe pick a weed, are emerging models for community-managed spaces. Another example of “caring by enjoying” encourages gardens to host events that invite non-garden people, for example, with backpack giveaways, coat drives, free haircuts, tasty food, and live music. This clear invitation creates a “goodwill gateway” to invite folks back for volunteer work and planting days.

Internal visibility is essential for garden leaders to continue the work they are doing in their community. New garden leaders, when provided a guide on “what to expect in community-management”, are less likely to be surprised when challenging things happen, and more likely to recognize it as an opportunity to exercise their community-management muscle. NeighborSpace provides an orientation for new garden leaders that is explicit, light in tone, and pragmatic about what will likely happen in a community garden. Generated by more seasoned leaders, this guide includes reflections on volunteers not showing up for workdays, vegetables getting stolen, and conflict resolution policies. This normalizing of likely occurrences ensures that when they happen, leaders are prepared, and sometimes even excited, to meet the challenges. This internal visibility goes a long way to creating a more resilient community group that feels supported and curious about the complicated nature of community-managed care.

Outward visibility to the bigger municipal and foundation players can be challenging, but there are opportunities to be proactive; NeighborSpace gets out ahead of future challenges by writing a yearly letter to commissioners about who NeighborSpace is, works with funders, writes letters to city department heads, and meets with aldermen to explain the nature of community-managed work and the value of this human and social infrastructure. It is still, unfortunately, the case, however, that the lion’s share of funding, both public and private, is focused on or limited to physical infrastructure, while there are fewer resources available for the human investment it takes to steward gardens. The cost of this gap between image and reality can leave some funders out of touch, and community stewards discouraged and overworked. Of utmost importance, then, is to continue filling in the blanks, and we hope other practitioners will be encouraged to grab this fill-in-the-blank baton, this unique framework, and diagram the true but sometimes invisible social infrastructure work going on “under the hood” of community gardening.

Conclusion

While NeighborSpace is working to “explain harder than we think,” it is still the case that a simplified story of community gardens can blunt the real work going on in community gardens. In turn, the resources available for advancing community-managed work (e.g., capital, urban agriculture) don’t always match the resources needed (e.g., community organizing, neighbor stewardship). There is not one magic framework that will tell the true story of community gardens, but it is crucial that we take seriously and pay attention to the profound work occurring in community-managed garden spaces and tell the story that does these efforts justice.

There are many claims in the literature that community gardens and related community-managed open space help to address issues of disconnection and isolation and set the conditions for improved community health. Here we’ve used an in-depth case study of NeighborSpace as a city-wide garden group to model and share some of the key drivers and outcomes of community-managed open spaces that are uniquely beneficial to our cities and towns. This experimental framework for social infrastructure visibility builds both a visual and structural language for allowing gardens to tell more complete stories.

Lindsay Campbell1, Robin Cline2, Ben Helphand2, Paola Aguirre2, Sonya Sachdeva2, Michelle Johnson1, Erika Svendsen1

New York1 and Chicago2

about the writer

Robin Cline

Robin Cline serves as Assistant Director of NeighborSpace, an urban open space land trust in Chicago. Robin is also the part-time executive director for the art group OperaMatic, a site-specific artist group that activates public spaces in Humboldt Park and Hermosa with participatory art.

about the writer

Ben Helphand

For more than twenty years, Ben has focused on ways to help communities have a direct hand in the creation and stewardship of the built environment. He is the Executive Director of NeighborSpace, a nonprofit urban land trust dedicated to preserving and sustaining community-managed open spaces in Chicago.

about the writer

Paola Aguirre

Paola Aguirre Serrano is an urban designer and partner at Borderless since 2016. She has served as Commissioner of Chicago Landmarks and the Cultural Advisory Council of the City of Chicago, and currently serves in the Scholarly Advisory Committee for the National Museum of the American Latino. Paola received a B. of Architecture from the Institute Superior de Arquitectura y Diseño de Chihuahua, and M. of Architecture in Urban Design from the Harvard School of Design.

about the writer

Sonya Sachdeva

Sonya Sachdeva is a computational social scientist with the US Forest Service in the greater Chicago area. She utilizes machine learning and other computational methodology to understand the socio-cultural factors that shape environmental values and behavior.

about the writer

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

Acknowledgments: All Partnerships Lab participants and TNOC Summit Caring in Public attendees, including Laura Landau, Georgia Silvera Seamans, Natalie Campbell, Nora Almeida, Sophie Neuhaus, Sarah Fox Tracy, Bep Schrammeijer, Paula Acevedo, Pete Ellis, Gitty Korsuize, Tuba Atabey, Neda Puskarica-Stojanovic, Yaritza Guillen, Natalie Perkins, Staice Martin, Francesca Birks, Samantha Miller.

References

Campbell, Lindsay K., Svendsen, Erika, Johnson, Michelle & Laura Landau. (2021): Activating urban environments as social infrastructure through civic stewardship, Urban Geography, DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2021.1920129.

Campbell, Lindsay K.; Svendsen, Erika; Sonti, Nancy Falxa; Hines, Sarah J.; Maddox, David, eds. 2019. Green Readiness, Response, and Recovery: A Collaborative Synthesis. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-P-185. Newtown Square, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 358 p. https://doi.org/10.2737/NRS-GTR-P-185.

Connolly, James J., Svendsen, Erika S., Fisher, Dana R., & Campbell, Lindsay K. (2013). Organizing urban ecosystem services through environmental stewardship governance in New York City. Landscape and Urban Planning, 109(1), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.07.001

Fisher, D. R., Campbell, L. K., & Svendsen, E. S. (2012). The organisational structure of urban environmental stewardship. Environmental Politics, 21(1), 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 09644016.2011.643367.

Klinenberg, Eric. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life. Crown Publishing.

Landau, Laura F.; Campbell, Lindsay K.; Svendsen, Erika S.; Johnson, Michelle L. 2021. Building Adaptive Capacity Through Civic Environmental Stewardship: Responding to COVID-19 Alongside Compounding and Concurrent Crises. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities. 3: 705178. 14 p. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.705178.

McMillen, Heather; Campbell, Lindsay K.; Svendsen, Erika S.; Reynolds, Renae. 2016. Recognizing Stewardship Practices as Indicators of Social Resilience: In Living Memorials and in a Community Garden. Sustainability. No. 775. 8(8): 26p. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8080775.

Svendsen, Erika, & Campbell, Lindsay. (2008). Understanding urban environmental stewardship. Cities and the Environment, 1(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.15365/cate.1142008.

Leave a Reply