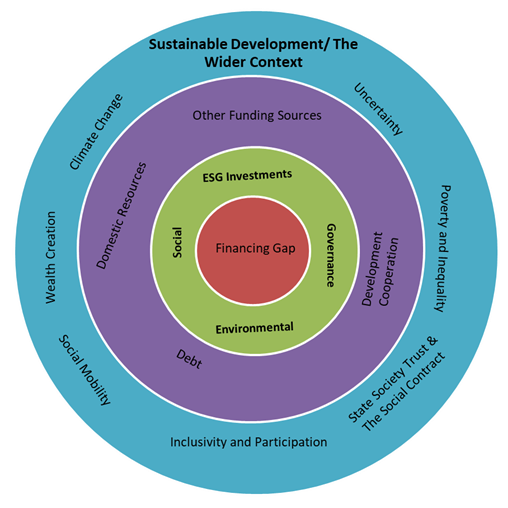

ESG could contribute to and compliment other initiatives and efforts to ensure multi-stakeholders work together to achieve sustainable development while addressing historic social inequities and challenges in developed and developing countries.

Background to the Sustainable Financing Gap

Globally, challenges in making our cities resilient are multi-dimensional and are on the rise. According to the 2023 Sustainable Development Goals Report, over half of the global population currently resides in urban areas, a rate projected to reach 70% by 2050. Approximately 1.1 billion people currently live in slums or slum-like conditions in cities, with 2 billion more expected in the next 30 years. The rapid growth of cities—a result of rising populations and increasing migration—has led to a boom in mega-cities[i], especially in the developing world, and slums are becoming a more significant feature of urban life. Cities occupy just 3% of the Earth’s land but account for 60 to 80% of the energy consumption and at least 70% of carbon emissions.

With more than 80% of global GDP generated in cities, urbanisation can contribute to sustainable growth through increased productivity and innovation. However, the speed and scale of urbanisation bring challenges, such as meeting accelerated demand for affordable housing, and viable infrastructure including transport systems, basic services, and jobs, particularly for the nearly 1.1 billion urban poor who live in informal settlements to be near opportunities. Rising conflicts contribute to pressure on cities as more than 50% of forcibly displaced people live in urban areas[ii]. Making cities sustainable means creating career and business opportunities, safe and affordable housing, and building resilient societies and economies. It involves investment in public transport, creating green public spaces, and improving urban planning and management in participatory and inclusive ways[iii].

It is estimated by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the International Energy Agency (IEA), that roughly $2.6 trillion is required every year until 2030 to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and stay on course toward a net-zero society by 2050[iv]. Furthermore, recent estimates put the global annual municipal infrastructure funding gap at US$3.2 trillion. However, the global economic outlook remains fragile amid a convergence of crises that are threatening to further reverse progress on the Sustainable Development Goals. The United Nations World Economic Situation and Prospects 2023 projects that global growth will decelerate to 1.9 per cent in 2023. The 2023 Financing for Sustainable Development Report finds that SDG financing needs are growing, but development financing is not keeping pace. If left unaddressed, a “great finance divide” will translate into a lasting sustainable development divide.

The Mid-Term Review of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction concluded that despite increases in direct and indirect economic impacts of disasters, investments in disaster risk reduction and efforts to de-risk investment remain inadequate. In the past 20 years, climate-related disasters have almost doubled. Developing countries need an estimated $70 billion annually for adaptation. Disaster risk reduction-related Official Development Assistance (ODA) has, however, barely increased, with only 0.5 per cent from 2010 to 2019 dedicated to disaster risk reduction in the pre-disaster phase―a marginal improvement from the 0.4% of the 1990–2010 period. This financing gap is yet to be addressed.

This financing gap may appear huge but compared to annual global savings and other large financing markets, it is achievable. The availability of capital is large enough to solve global infrastructure needs. Against the above background, at the international level, several UN-led, multi-stakeholder initiatives emerged to unlock significant capital flows to inclusive, sustainable urbanisation projects, e.g., the Cities Investment Facility (CIF). Concurrently, at the low to middle-income countries level, there is agreement that a paradigm shift from a granting model to a financing model is crucial in keeping up the pace towards attaining the SDGs. This essay examines one particular vehicle for channeling private investments and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) towards sustainable development, namely the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) metrics, with particular emphasis on the social metrics. This is particularly important as a 2019 Morgan Stanley Asset Owners survey found that sustainable investing is gaining traction among asset owners, where 80% said that they actively integrated sustainable investing in 2019, up 10 percentage points from 2017.

ESG Metrics

The E in ESG considers a company’s energy use, and environmental impact as stewards of the planet and how a company uses resources across the board specifically scope one, two, and three emission sources[v]. Factors considered include energy efficiency, carbon emissions, biodiversity, air and water quality, deforestation, and waste management.

The S in ESG is the social criterion that examines how a company fosters its people and culture and how that has ripple effects on the broader community. Factors considered include inclusivity, gender, and racial diversity; employee engagement; customer satisfaction; data protection; privacy service to the community; human rights and labor standards.

The G in ESG is the governance criterion that considers a company’s internal system of controls, practices, and procedures and avoidance of violations. It aims to ensure transparency and industry best practices and includes dialogue with regulators. Factors considered are the company’s leadership, board composition, executive compensation, audit committee, structure, internal controls, shareholder rights, and political contributions.

Organizations that do not consider these environmental, social, and governance factors and risks may face unforeseen financial risks and investor scrutiny. Transparency is critical to the process, where transparent reporting enables stakeholders to gain a clear picture of a company’s direction and progression. Stakeholders need visibility on the progress as well as the goals.

The critical role of S and G in ESG

The year 2020 was the biggest year for ESG-investing yet. The events of 2020 have shown that social factors are as much on investors’ minds as are environmental or governance factors. But while the “E” is the easiest one to codify and is now mainstreamed, including in real estate investment firms, the “S” and “G” are often more implicit, yet critical.

The “S” and “G” can help address society’s toughest problems, such as economic opportunity and inequity. These are issues that, historically, investors exacerbated by not always considering the negative externalities or the long-term impacts of their investments on society at large. But investors are, increasingly, changing course. For example, BlackRock—the world’s largest asset manager—has decided to focus on ESG because they recognize that rising income inequality poses long-term business risks. In fact, the 2020 World Economic Forum’s inaugural Social Mobility Report finds that increasing social mobility, a key driver of income equality, by 10% would not only benefit social cohesion but also boost economic growth by nearly 5% over the next decade. This has specific and significant implications for each economic sector including the real estate and the hotel sectors.

While developing countries have a considerable sustainable development financing gap, the potential for ESG to address this gap is significant. However, ESG investments are not yet sufficiently being adopted across the different sectors in developing countries. The next two sections review some of the best practices in the USA and Europe, as a way to showcase the potential for ESG impact investments throughout the world.

USA: The critical role of the real estate industry in the development of inclusive cities

Almost every major development project requires significant loans from banks or equity from third-party investors, who are increasingly willing to lend capital to real estate companies that are pursuing projects with real social impacts. Developers are recognizing that the traditional development process — which sets up community members and developers as opponents—needs to change. It is now recognised that Real estate, which historically played a significant role in perpetuating racial and class inequities, could play a significant role in offsetting them, too. Developers who decide to pursue more inclusive and equitable projects will be more likely to receive capital from investors. Elaborating on what this “S” in ESG means for real estate, should be a multi-stakeholder effort including affected communities, and should not be restricted to developers and investors. This is particularly true as it is not just developers that will benefit, but our cities will, too.

Indeed, it is everyone’s task to search, identify, and develop ideas that would make real estate development in cities more inclusive and equitable. This should include new ideas on ownership, wealth creation, social mobility, and economic opportunity approaches. The main question that should be addressed is how real estate can deliver better social outcomes for communities while transforming development into a powerful tool for creating more equitable, inclusive cities.

Leveraging ESG is an important way to catalyze change in the development industry. Financial institutions can be drivers for change, as developers respond to what financial institutions demand. Developing socially-minded metrics is a key step towards helping the alignment of developers and investors to work in locations in the absence of social infrastructure, economic infrastructure, and/or housing and other physical infrastructure.

Metrics is one of the issues that must be agreed upon by different stakeholders within the industry, including the real estate side and the institutional investor side. In this context, it should be recognised that social metrics are more complex than environmental metrics, where developers generally measure monthly building emissions, carbon intensity materials, and/or how much renewable energy is being generated by solar panels.

Social metrics are more complex as they try to address and measure long-term, endemic challenges, to be measured over time. Most development projects track few social outcomes, such as the number of affordable housing units created, the number of construction jobs generated, and/or the number of community engagement hours undertaken. However, none of these are particularly long-term in nature.

Social mobility metrics

Some of these longer-term metrics include for example youth enrichment programs in partnership with universities that can positively impact high school graduation rates and university enrollment rates for children in underperforming schools. Social metrics that need to be measured go beyond providing jobs —like construction, maintenance, or retail jobs to community members. In this case, by helping people graduate high school and attend college, such youth enrichment programs fundamentally improved the likelihood of social and economic mobility of local youth.

Creating long-term social metrics is not enough to instigate more equitable and inclusive development. Creating “S” metrics in collaboration with community members has the potential to align communities’ needs with investors and developers. Hence, the engagement of community members is crucial. In this manner, equitable development is best understood and practiced as an ecosystem-based initiative of private, public, and community-based partners to enact solutions together. Recent trends show that investors are now adopting ESG-based investments, which are driving returns, with the top 10 ESG funds outperforming the market in 2022.

Wealth building opportunities and metrics

New metrics can incentivize new models that have equity at the core. For example Community Investment Trusts Model allows members in a predominantly immigrant and refugee community to share ownership of a commercial building while tracking parameters like the number of women investors, first-time investors, and the dividends earned as a measure of how well the project is giving people new access to wealth-building opportunities.

Another wealth-building model is the neighbourhood Real Estate Investment Trusts (REIT), which aims to measure how much people who have been denied wealth-building opportunities can grow multi-generational wealth over time. These initiatives put the community in the driver’s seat to participate in real estate development, in a way that has usually been limited to wealthy ‘elite’ developers or landowners. Other measures that need metrics include i) how much decision-making power a community has in a project, ii) how much wealth community individuals will generate from a project’s success, and iii) how well a project responds to community needs. These parameters may be measured, year over year, in order to determine how successful a project truly is.

Social impact investing in Europe and the UK

In 2011, the European Commission launched the Social Business Initiative to support the development of social enterprises, social economies, and social innovation. It led to important developments, such as the formation of the Expert Group on Social Economy and Social Enterprises (GECES), which brings together representatives of private and civil sector organizations, associations, and networks to communicate with national governments and advise the European Commission on social economy policies. The public sector supports impact investing in Europe at regional and national levels, by helping build both the demand and supply of capital, catering to the needs of social enterprises as recipients of funding and to the needs of investors and intermediary organizations as funders. The EU taxonomy on sustainable finance helps investors clearly measure sustainability by considering the economic impact of climate change, but no other social or environmental issues, on financial performance.

In 2012, Britain established Big Society Capital, a wholesale investment institution focused on combined social and financial returns. Britain also established the Social Impact Investment Task Force (SITF) in 2013, which was accompanied by the creation of policies, investment funds, and specialized financial tools.

Development in Europe, and across different sectors, varies. The variability shows that investors and policymakers need to account for the field’s different levels of maturity in national, sub-national, sectoral, and municipal markets.

The threat of greenwashing

Sustainable Finance involves taking ESG considerations into account when making investment decisions in order to provide sustainability benefits for organizations, communities, and the world as a whole. However, sustainable investments are expected to make a financial return as well as deliver environmental and social benefits. On the other hand, in some instances, businesses and the investment community engage in greenwashing[vi] practices making false marketing claims. Greenwashing can occur at the entity level, at product level, or at service level, including advice and payment services.

Greenwashing consists of two clear components: misleading intentionally or misleading through negligence. The first category consists of knowingly misrepresenting the sustainability-related characteristics of a particular investment or product with the intention to mislead. The second refers to situations of gross negligence where claims are made without taking reasonable steps to ensure the veracity of the ‘sustainability’ claim. The fact that there is no common definition of sustainable investment in the context of a rapidly evolving legislative framework does not justify negligence.

Greenwashing again shows the importance of i) suitably chosen metrics that can measure impact; and ii) the importance of engagement of all stakeholders, including the impacted communities, in validating the reporting process.

The role of regulations

The E indicators and metrics have been sufficiently elaborated over the past few decades, which makes it easier for the service/product/entity to report on environmental sustainability, and it also makes it easier for the regulators to identify greenwashing. However, this is not yet the case for the S indicators, particularly the long-term S indicators related to social mobility, wealth creation, and poverty reduction for the most vulnerable. This makes it harder for service providers to report on social sustainability indicators and equally difficult for regulators to identify any “social-washing”.

A recent review of the main USA, EU, and UK[vii] ESG regulations shows a general focus on environmental and climate-related metrics. The European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) provide more detailed, and distinct, Environmental, Social, and Governance Standards. It has four social standards i) ESRS S1 Own workforce; ii) ESRS S2 Workers in the value chain; iii) ESRS S3 Affected communities; iv) ESRS S4 Consumers and end-users. Notwithstanding the importance of the above, more effort should be directed at developing S metrics capable of effecting the required change of social mobility, asset ownership, wealth creation, and other economic opportunities.

ESG+R

Even when ESG investments are designed to effect long-term change in terms of environmental sustainability, governance, social mobility, and poverty reduction, they would still need to be resilient to natural hazards and to climate change in order to be truly long-term. This is the last letter that completes the picture, the need for resilient ESG or RESG.

Closure

ESG could contribute to and complement other initiatives and efforts to ensure multi-stakeholders work together to achieve sustainable development while addressing historic social inequities and challenges in developed and developing countries. It is possible to develop financially viable projects that help historically disinvested communities generate wealth, give regular people a seat at the table, and bring equitable growth and prosperity to neighbourhoods that have been left behind. For the future of all our cities, we must.

Fadi Hamdan

Athens

[i] Megacities are defined in this context as having a population of 10 million or more.

[ii] Urban Development Overview (worldbank.org)

[iii] 2023 Sustainable Development Goals Report

[iv] The 2023 Financing for Sustainable Development Report

[v] Scope 1 emissions are “direct emissions” from sources that are owned or controlled by the company. Scope 2 emissions are the emissions released into the atmosphere from the use of purchased energy. These are called “indirect emissions” because the actual emissions are generated at another facility such as a power station. Scope 3 emissions include all other indirect emissions that occur across the value chain and are outside of the organisation’s direct control.

[vi] The European union definition of green washing is the practice of gaining an unfair competitive Advantage by marketing a financial product as environmentally friendly when in fact it does not meet basic environmental standards.

[vii] USA Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures (Proposed Rule); EU: Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS); UK: The Companies (Strategic Report) (Climate-related Financial Disclosure) Regulations 2022; The Limited Liability Partnerships (Climate-related Financial Disclosure) Regulations 2022.

Leave a Reply