Is neighborhood planning worth doing? We argued in our last blog entry (Part 1 of this series) that neighborhood planning has the potential to be transformative in improving community resilience, but that it also has a dark side. It can be divisive both spatially—by setting clear geographic ‘limits’ that signal exclusion or exclusivity—and socially, by putting local interests ahead of broad concerns such as urban connectedness and complexity. In this follow-up blog, we propose that neighborhood planning is worth doing if it integrates four key components of ‘nested’ neighborhood planning that link neighborhood-scale planning to the work of ensuring better outcomes for the city as a whole: (1) social innovation, (2) community-development practice integrated with theory, often simply termed ‘praxis’, (3) neighborhoods without borders, and (4) a vision of ecological democracy.

These four components are based on our practical experience with neighborhood planning and our examination of academic and professional literature on planning and community development. We speak normatively here, in terms of what ought to be done. We outline a multi-scalar approach that links dimensions of thinking, planning, and building which are often disparate: integrating scales from the neighborhood to the city to the city-region, integrating action across domains of civil society and the state, and integrating value systems of urban ecology and participatory democracy. In our next and final blog entry of this series, we will present a Montréal case study, and examine whether nested neighborhood planning can offer building blocks for better cities in a wide range of geographic, political, and cultural contexts, if all three types of integration are present.

Neighborhood planning component 1. Social innovation

Social innovation is both a new label for old practices and a significant new notion. As a concept, it has evolved in two important ways: (i) to make the connections between tangible ‘bottom-up’ actions where people take their own initiatives to effect change and much-needed transformations in governance; and (ii) to provide meaning that is both usefully ideological and critically robust, so that it can play an active role in debates of politics and social science (Nussbaumer and Moulaert, 2007: 73-78; in Moulaert et al., 2010: 7). How can we understand the dynamics of social innovation at the neighborhood level? Useful frameworks are found in a collection edited by Moulaert et al. (2010) titled Can Neighbourhoods Save the City? Community development and social innovation, in which contributions from various authors uncover the conditions and prerequisites for making neighborhood-scale initiatives pertinent at the city scale and beyond. The editors contend that ‘socially innovative neighbourhood initiatives’ share three objectives:

- to satisfy human needs which are unmet by the state and markets;

- to provide access rights which enhance human capabilities and are empowering to people and social processes; and

- to change social relations and power structures that lead to more inclusive governance.

In their case studies from 10 European cities, the authors show how neighborhoods can be pivotal sites for driving social innovation, which typically happens through civil-society organizations (CSOs) working not only within local neighborhoods, but also working to connect them with the broader urban context, building bridges to the political realm. A vital success factor in the cases was a capacity and perspective of glocalism, or integration of spatial scales from neighborhood to city to global. A glocal perspective reminds us that ‘localist’ initiatives hold local culture and community interests as exclusive or predominant forces for determining development; this hinders the trans-local relationships, policies, and processes crucial for resilient and livable cities (Rohe, 2009; Moulaert et al., 2010).

In our own work, we have found another key reason that socially innovative organizations are poised to contribute to resilient and livable cities through neighborhood-based planning. We call this the expectations-motivation differential. This refers to a dichotomy: it is often in the (rational) interest of state institutions to keep the expectations of citizenry low, whereas progressive civil-society organizations seek to ‘raise the bar’ by inspiring people to have higher expectations for the collective work of city-building. In this perspective, the aim of planning is to inspire and educate people about possibilities for the city, and to explore the possibilities for learning and positive change at the local scale. When ordinary people feel empowered to plan for change in their own neighborhoods by critically assessing the current context, analyzing power dynamics and external forces, understanding that ‘a different city is possible’, and planning for a better future, it stands to reason that they will be more likely to take part in collective action for social change, thereby contributing to creating a more resilient and livable city.

Neighborhood planning component 2. The praxis of community development

The notion and praxis of ‘community development’ can be defined as thoughtfully designing, continually learning from, and creatively acting on processes of collective engagement associated with neighborhood planning. In other words, we need to strive for social learning by designing engagement processes that lead to knowledge creation, which can be translated into action that will feed the continued refinement of engagement processes.

Our notion of community-development praxis is influenced by work found in several bodies of literature including collaborative and participatory planning, community development, education and social science. We particularly value the idea of ‘phronesis’ or ‘practice-based wisdom’. To unravel what we mean here, we draw on Ledwith (2011a) to start with the notion of praxis as a synthesis of practice and theory, reflection and action, thinking and doing; we can then speak of critical praxis, which refers to the collective endeavor of making sense of the world and our own actions in order to transform it. Through praxis people gain critical awareness of their own condition and collectively work to shift balances in relationships of power in order to work toward social justice, empowerment, and liberation.

Paul Piccone calls praxis “that creative activity which reconstitutes the past in order to forge the political tools in the present to bring about a qualitatively different future” (1976: 493); similarly, Innes and Booher (2010: 89) suggest that

“… [e]ffective collaboration depends on praxis. That is, it depends on extended practical experience deeply informed by theorizing and reflection. Those who engage in collaboration build their capacity and intuition about how to proceed, while at the same time building theory about when and how collaboration can work. Praxis is practice interwoven with theory and theory informed by experience in the spirit of pragmatism.”

Margaret Ledwith (2011b) describes community development praxis as a ‘contested space’ between top-down and bottom-up approaches in which state and civil society participants continually negotiate their ways of working together and challenging one another. Drawing on Flyvbjerg (2001), she has argued that praxis ought to intermingle with phronesis, an approach to social science that emphasizes practical knowledge and practical ethics, which are based on context-dependent, pragmatic action and practical value-rationality (Ledwith, 2011a). Thus, the praxis of community development is unabashedly value-laden. Its aim is collective action for social change, and it is principled on social justice and a sustainable world, a critical analysis of power, and popular education for participatory democracy (Ledwith, 2011b; Ledwith and Springett, 2010).

If neighborhood planning processes are to be transformative in their capacity to contribute to more resilient and livable cities, they must be based on a strong ethos of community development (comprising both physical transformations and the qualitative development of individuals). If community development is to be carried out effectively, sustainably, and in a transformative way, the associated processes of local governance must be participatory and collaborative, building improve neighborhood capacity to manage change over time. This means that neighborhood planning processes must enable community members to mobilize their existing skills, reframe problems, work cooperatively, and use community assets in new ways. Principles of self-help, self-organization, and participation can guide flexible processes of revisiting neighborhood plans over time in order to identify concerns, continue dialogue, explore alternatives, reconsider priorities, and take effective action.

Neighborhood planning component 3: Neighborhoods without borders

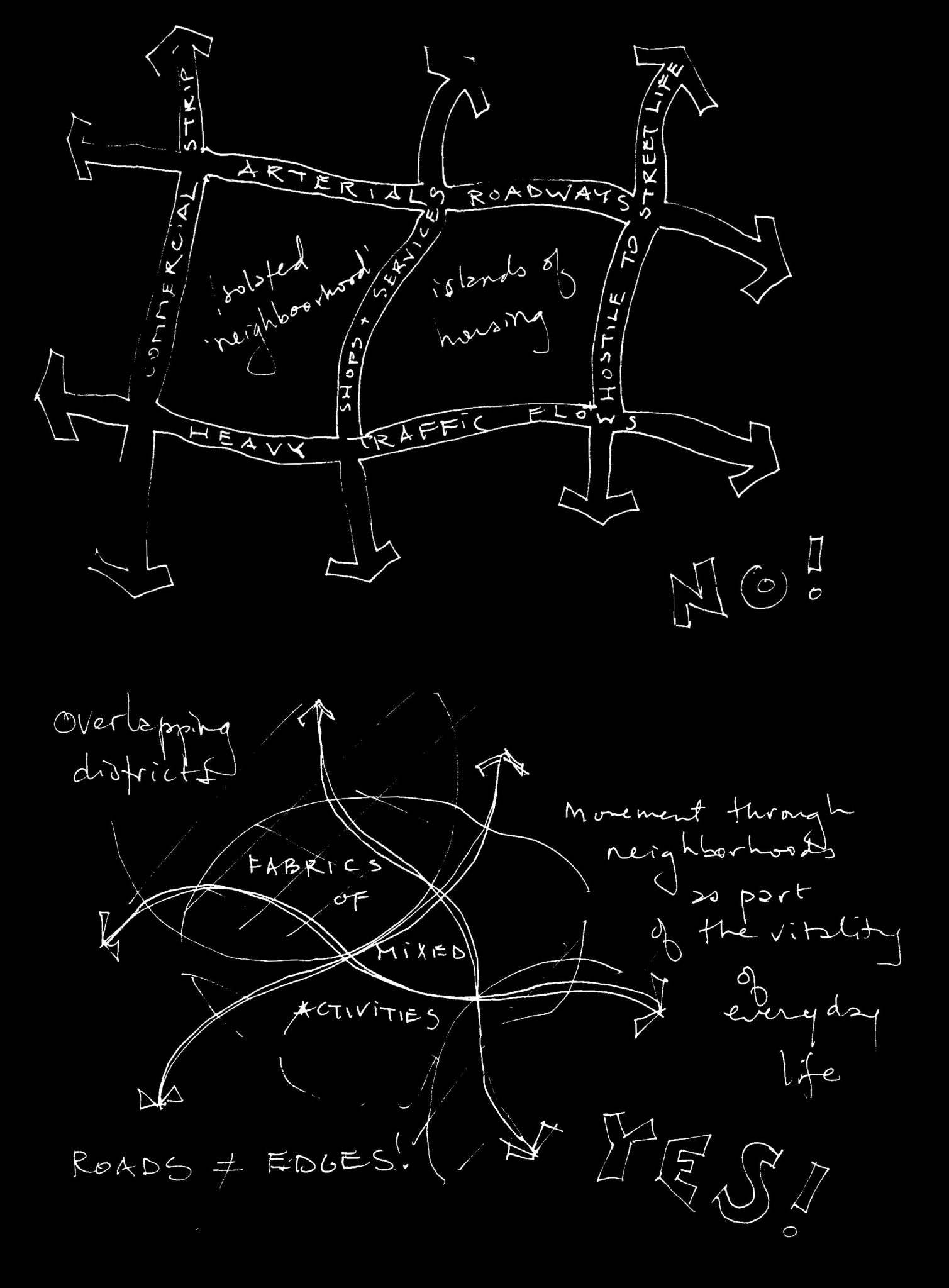

A neighborhood plan typically defines an urban district and its boundaries (which might be natural or built elements, such as rivers, steep slopes, railroad tracks and/or large parks). Often the ‘official’ limits for planning follow some kind of public right-of-way, such as streets, roads, and highways. Municipal boundaries often run down the middle of rights-of-way, thus dividing these public spaces into separate jurisdictions. The logic here is not merely convenience or efficiency; it has long been presumed that clear neighborhood edges are needed in order to make neighborhoods ‘legible’ and to provide distinct, easily-recognized character (see e.g. Banerjee and Baer, 1984; Lynch, 1981; Perry, 2007 [1929]).

Our proposition of ‘neighborhoods without borders’ challenges the conventional wisdom of neighborhood planning in North America—that is, the usual prescription that neighborhoods be clearly demarcated by physical edges (usually arterial roads), derived from Clarence Perry’s ‘neighborhood unit’ as discussed by Banerjee and Baer (1984), Greenberg (1994), and Keating and Krumholz (2000). Instead, we argue that neighborhoods should be defined to encompass not only a range of activities, including housing, businesses, and community services, but also the public spaces of arterial and commercial streets often relegated to the outside margins. Neighborhoods defined as overlapping or nested configurations prevent the ‘spaces in between’ prone to becoming zones of social and spatial marginality. This situation is often exacerbated by superhuman-scaled arterial roads that can threaten the safety of residents and urban quality of local neighborhoods, contributing to health problems through pollution and accidents while often reducing opportunities for better integration of nature and biodiversity in dense urban environments.

Some argue that the spaces ‘separating’ neighborhoods should be a different category of space unto itself devoted to serving larger city functions. The logic could be seen as that of the ‘city efficient’ of the early 20th century, where activity areas were separated from transportation zones containing high-capacity roadways (see e.g. Van Nus, 1979). We instead argue that these ‘in-between zones’ should be defined as part of neighborhoods, enabling stakeholders to challenge the power structures that govern these spaces based on an understanding of how they are integral to creating better neighborhoods and cities. In a city of neighborhoods characterized by resilience, livability, and people-centered urban design, the whole cannot be greater than the sum of its parts. Cities must be seen holistically as containing overlapping and nested neighborhoods. Those parts should include a range of uses and street types; they cannot be an expression of formally or informally ‘gated’ enclaves—the solipsistic ‘burbclaves’ chillingly described by Neal Stephenson in his dystopic 1992 novel Snow Crash.

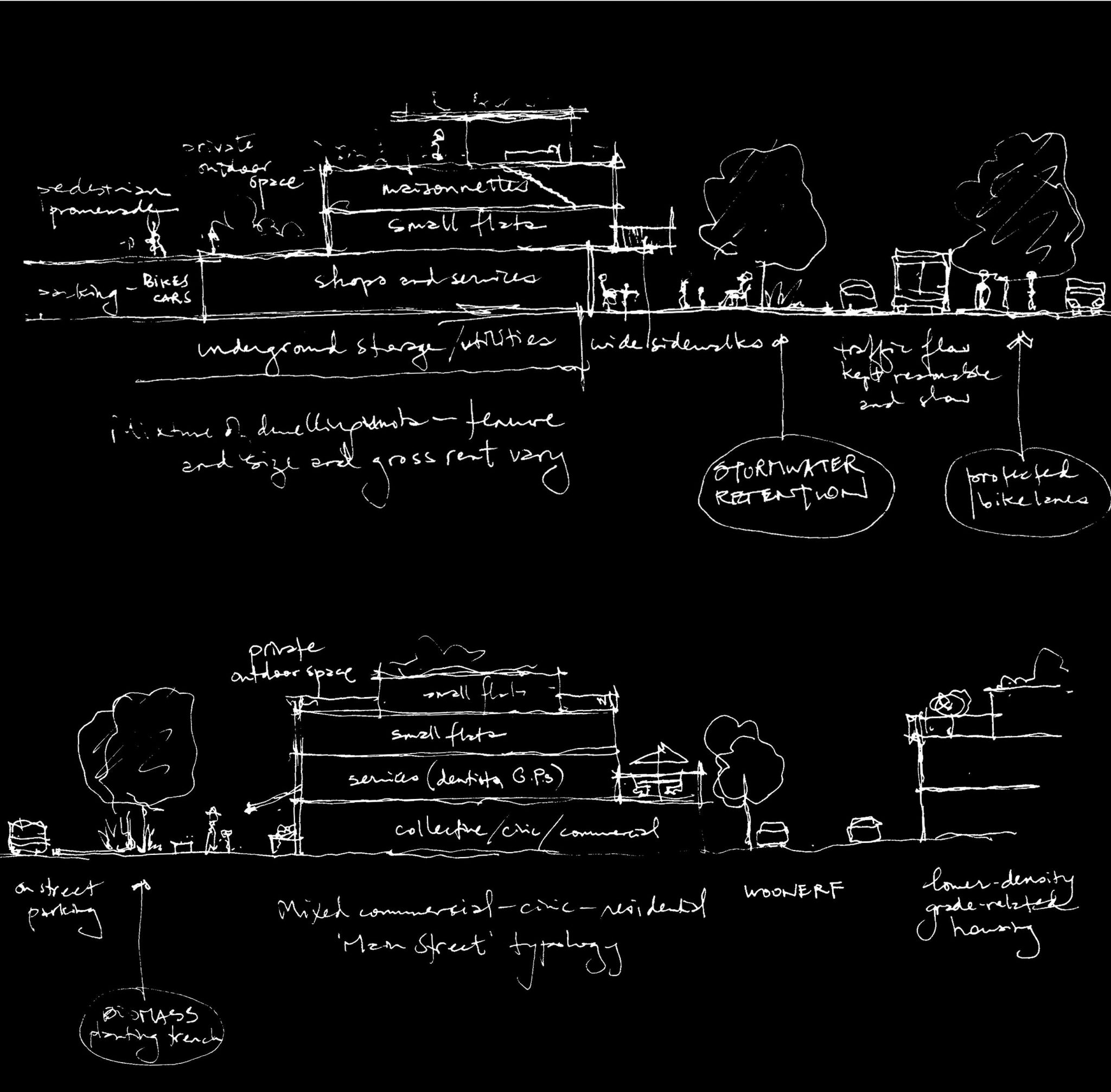

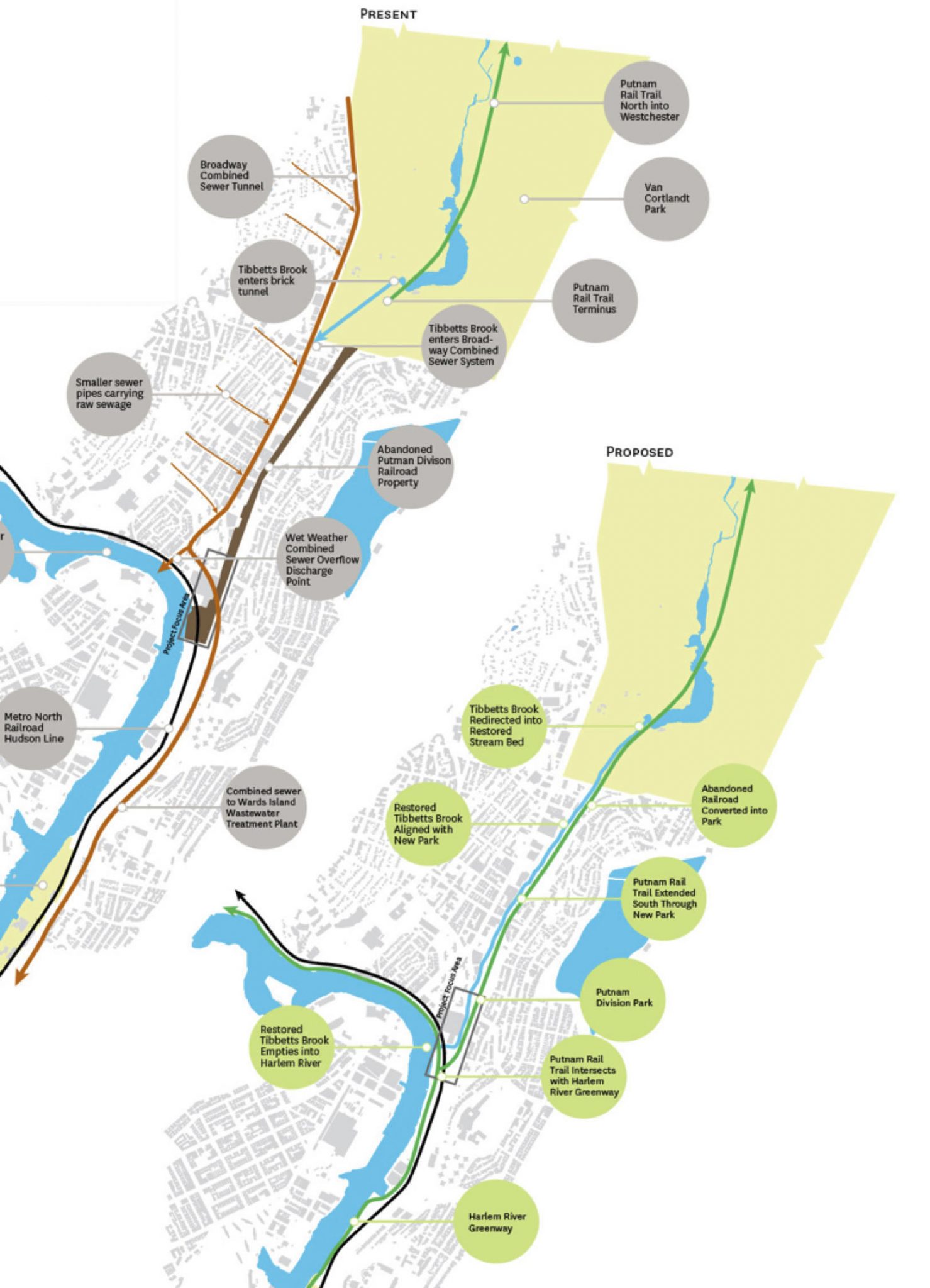

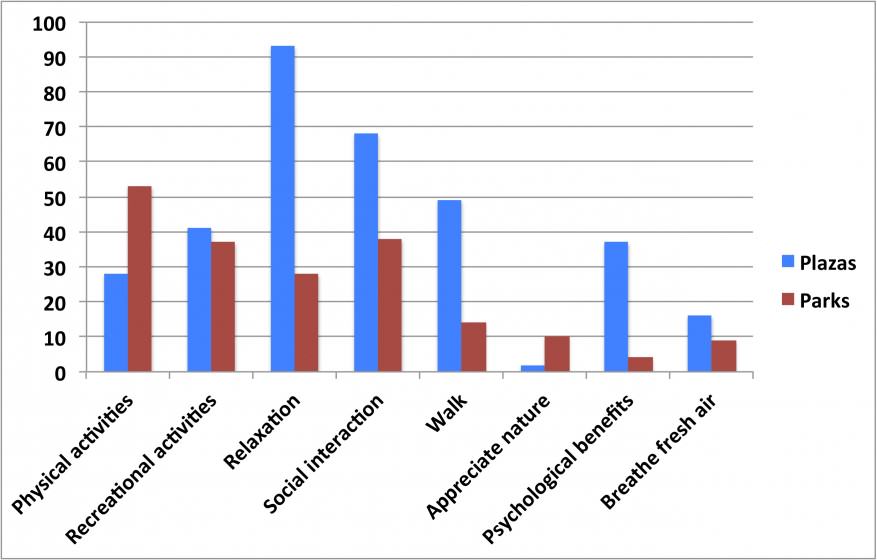

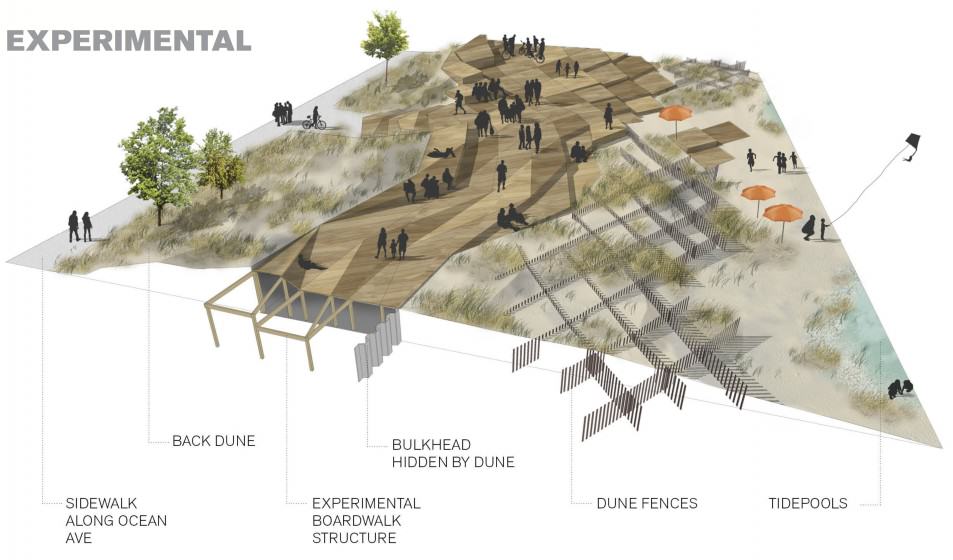

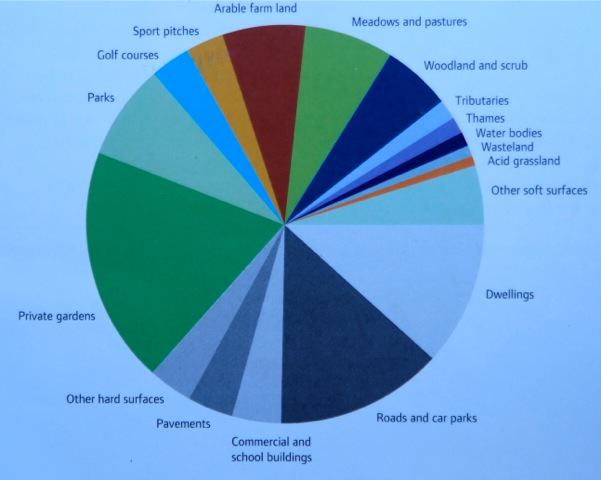

Good neighborhood plans should strengthen the public realm of neighborhoods. These shared spaces tend to garner attention, enthusiasm, and collective action, and we cannot forget that the largest share of public space in cities is occupied by streets. It could be argued that neighborhood streets represent the greatest opportunity for transformation in policy and practice toward building better cities. By rethinking our streets and the wide set of externalities that result from their construction, configurations, and use, we can reimagine how these spaces can provide all sorts of beneficial functions: more space for people walking and bicycling; vegetation and other forms of biomass, including urban agriculture and biodiversity corridors; playgrounds and the urban ‘living rooms’ seen in great cities large and small around the world (for examples, see Beatley, 2011; Gehl, 2010; Newman and Jennings, 2008; Register, 2006; Whyte, 1980).

This prescriptive component is about rethinking how public spaces—specifically streets—in cities are used in an attempt to reverse over time the tendency to carve up cities with highways and instead to think of how these spaces can better integrate neighborhoods to redefine routes in cities so that they can better serve not only the needs of people walking, cycling, and using mass transit, but also as routes that can better facilitate increased nature and biodiversity.

It is important to clarify what we are not arguing. We do not contend that cities ought not to have clear edges. Clear boundaries around cities can be vital to contain urban sprawl and to provide good access to nature and biodiversity. We do not argue that resilient and livable cities must be based on specific templates for neighborhood design. Rather, we are asserting that the neighborhood is an appropriate scale to effectively plan for better cities, particularly in already-built contexts.

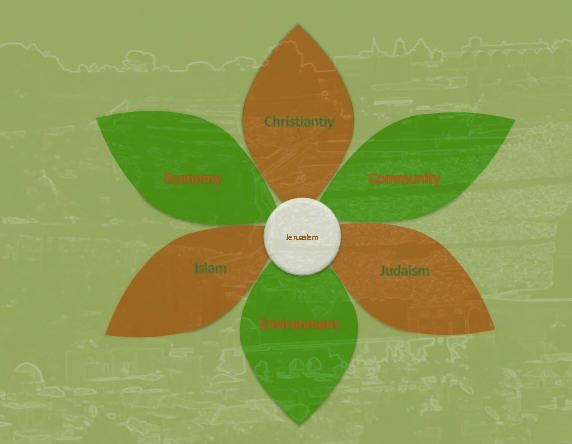

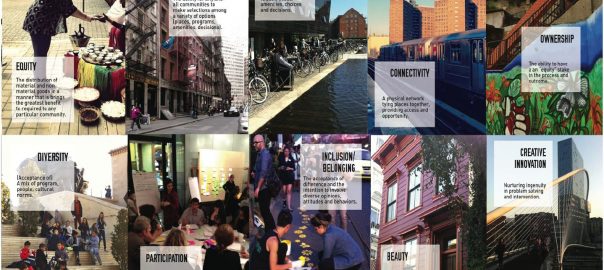

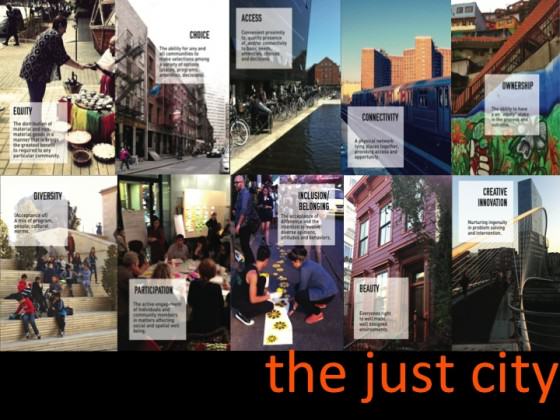

Neighborhood planning component 4. Holistic ecological democracy vision

There is far more to resilient and livable cities than physical attributes. If there is no mechanism for the democratic engagement of citizens at the neighborhood scale to create better cities, no combination of good policies and planning will make a difference. Setting a vision for a better city from a neighborhood perspective is critical to bringing people together to organize collective action that will bring about social change. Neighborhood plans should contain a practical utopian vision for the neighborhood within the larger city, which is translated into medium-term policies and programs but also actions that can be taken on a short-term timeframe.

A holistic vision for a resilient and livable city is one of integral neighborhoods within an ecological democracy. By integral neighborhoods we mean what Richard Register and Paul Downton call ‘urban fractals’ or “portions of the city that embody the essential functions of the whole city on a smaller scale” (Register 2006: 128). Integral neighborhoods contain a mix of land uses to provide for housing and jobs, shops, and small manufacturing facilities. Key attributes include compact urban form, socio-economic diversity, organic agriculture, rooftop uses, and pedestrian-oriented streets. The natural and neighborhood environments relate synergistically, and biophysical characteristics, such as sun and wind conditions, play central roles in architectural and urban design and contribute to energy conservation. Compact design and mixed land uses provide for access by proximity, meaning that safe, affordable housing is provided near employment and services in ways that minimize car dependency and energy use (Register, 2006; UNEP, 2012).

Randolph Hester’s (2006) notion of ecological democracy is the joining of urban ecology with participatory democracy; in the specific endeavor of designing better neighborhood and city form, it is particularly useful for our discussion:

“Ecological democracy, then, is government by the people emphasizing direct, hands-on involvement. Actions are guided by understanding natural processes and social relationships within our locality and the larger environmental context. This causes us to creatively reassess individual needs, happiness, and long-term community goods in the places we inhabit. Ecological democracy can change the form that our cities take, creating a new urban ecology. In turn, the form of our cities, from the shape of regional watersheds to a bench at a post office, can help build ecological democracy.”

How is the neighborhood scale important to the lofty aspirations of ecological democracy? Hester (2006: 32) argues that this is the “domain of deliberative face-to-face ecological democracy.” It is through everyday experiences in the everyday environments of neighborhoods that social change occurs. However, given that the concept of (radical) ecological democracy may not be workable within the context of many countries, is it helpful to bring this vision into the dialogue of neighborhood planning processes?

We argue that it is precisely through participatory practices such as neighborhood planning for resilient and livable cities that we can raise expectations of the public and work to bring about social changes necessary to realize the kinds of neighborhoods for the cities we need. In his book Envisioning Real Utopias, Erik Olin Wright (2010) sets out a set of models for social transformation that are instructive for thinking about how we can achieve better cities. Depending on the wider political and institutional context of a place, strategies for transformation will vary. In most cases strategies can be seen as processes of change in which fairly small transformations contribute cumulatively to a qualitative shift in the logic and dynamics of larger social systems. In terms of neighborhood planning, these metamorphoses occur in what we have described above as the contested space of community development praxis between top-down and bottom-up. This is the space where civil society and the state meet—and cooperate (or not) to some degree, even if certain citizen stakeholders are sometimes completely excluded from official planning processes. Exactly how social transformation comes about is highly context-dependent.

Whatever the political, cultural, or institutional context, most people around the world live in some form of neighborhood. The variations are great in terms of what those neighborhoods look like, how they function, and whether they contribute to creating better cities. What is true for all neighborhoods is that they are fundamentally defined by (and for) people. When people decide to come together to work for change, great things can happen.

In our final blog entry (Part 3 of Neighborhood Planning for Resilient and Livable Cities), we will examine how a Montréal civil-society organization successfully undertook neighborhood planning and what can be learned from this experience for making better cities around the world.

Jayne Engle and Nik Luka

Montreal

References

Banerjee, T. K., & Baer, W. C. (1984). Beyond the neighborhood unit: residential environments and public policy. New York: Plenum.

Beatley, T. (2011). Biophilic Cities: Integrating nature into urban design and planning. Washington DC: Island Press.

DeFilippis, J., Fisher, R., & Shragge, E. (2010). Contesting community : the limits and potential of local organizing. New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Fennell, L. A. (2013). Crowdsourcing land use. Brooklyn Law Review, 78(2), 385-415.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2001). Making social science matter. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Forester, J. (1999). The deliberative practitioner: Encouraging participatory planning processes. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Harmondsworth (England): Penguin.

Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for People. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Greenberg, M. (1994). The poetics of cities : designing neighborhoods that work. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Guttman, N. (2010). Public deliberation on policy issues: normative stipulations and practical resolutions. In C. T. Salmon (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 34 (pp. 169-212). New York: Routledge.

Hester, R. T. (2006). Design for ecological democracy. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Innes, J. E. & Booher, D. E. (2010). Planning with complexity: An introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. New York: Routledge.

Keating, W. D., & Krumholz, N. (2000). Neighborhood planning (commentary). Journal of Planning Education and Research, 20(1), 111-114.

Kretzmann, P. & McKnight, J. L. (1993). Building communities from the Inside Out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets. Evanston IL: Institute for Policy Research.

Ledwith, M. (2011a). Community development: A critical approach (2nd ed.). Bristol : Policy Press.

Ledwith, M. (2011b). From ‘no such thing as society’ to ‘the big society’! Community development in changing political times. Presentation given at the University of Northampton, 25 October. Accessed online in March 2012 via http://www.slideshare.net/curtistim/margaret-ledwith-northampton-lecture-1-25-october-2011.

Ledwith, M. & Springett, J. (2010). Participatory practice: Community-based action for transformative change. Bristol : Policy Press.

Lynch, K. (1981). Good city form. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Moulaert F., Martinelli F., Swyngedouw E., & González, S. (Eds.). (2010). Can neighbourhoods save the city? Community development and social innovation. New York: Routledge.

Newman, P. and Jennings, I. (2008). Cities as sustainable ecosystems: Principles and practices. Washington DC: Island Press.

North, A. (2013). Operative landscapes : building communities through public space. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Nussbaumer, J. & Moulaert, F. (2007). L’innovation sociale au cœur des débats publics et scientifiques. In J. L. Klein and D. Harrisson (eds.). L’innovation sociale. Sainte-Foy QC: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Perry, C. (2007 [1929]). The neighborhood unit. In M. Larice & E. Macdonald (Eds.), The urban design reader (pp. 54-65). New York: Routledge.

Piccone, P. (1976). Gramsci’s Marxism: Beyond Lenin and Togliatti. Theory and Society, 3 (4), 485-512.

Register, R. (2006). Ecocities: Rebuilding cities in balance with nature. Gabriola Island BC: New Society.

Rohe, W. M. (2009). From local to global: One hundred years of neighborhood planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 75 (2), 209-230.

Sanoff, H. (2000). Community participation methods in design and planning. New York: Wiley.

Sarkissian, W. & Bunjamin-Mau, W. (2009). SpeakOut: The step-by-step guide to speakouts and community workshops. London: Earthscan.

Sarkissian, W. & Hurford, D. (2010). Creative community planning: Transformative engagement methods for working at the edge. London: Earthscan.

Stephenson, N. (1992). Snow crash. New York: Bantam Books.

Toker, U. (2012). Making community design work : a guide for planners. London: Taylor & Francis.

UNEP—United Nations Environment Programme (2012). 21 Issues for the 21st Century: Result of the UNEP foresight process on emerging environmental issues. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme.

Van Nus, W. (1979). Towards the City Efficient: the theory and practice of zoning, 1919-1939. In A. F. J. Artibise & G. A. Stelter (Eds.), The useable urban past: planning and politics in the modern Canadian city (pp. 226-246). Toronto: Macmillan.

Wates, N. (2000). The community planning handbook: How people can shape their cities, towns and villages in any part of the world. London: Earthscan.

Whyte, W. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Washington DC: The Conservation Foundation.

Wright, E. O. (2010). Envisioning real utopias. New York: Verso.

about the writer

Nik Luka

Nik Luka is a professor of urban design who specialises in transdisciplinary approaches to understanding urban form and cultural landscapes with a particular interest in the everyday interfaces of nature and culture as experienced by individuals.

However, in the last century, the situation has changed. These wetlands became a private property where their profitability prevailed over the common good. Changes in technology and economic conditions, coupled with the loss of social control, allowed the growth of the city beyond its limits. The filling and draining of wetlands through engineering has tried to hide the true nature of the city for decades.

However, in the last century, the situation has changed. These wetlands became a private property where their profitability prevailed over the common good. Changes in technology and economic conditions, coupled with the loss of social control, allowed the growth of the city beyond its limits. The filling and draining of wetlands through engineering has tried to hide the true nature of the city for decades.

Improving this relationship is going to take some time. I can’t promise a happy ending, of course, but ask you to remember three things: First, your goals for a sustainable, healthy landscape are parallel, not divergent. Keep that in mind when you seem to have momentary troubles communicating. Second, you are both driven to improve the landscape, not watch it continually degrade; remember you’re soul mates, at least in that way. Third, we live in a rapidly changing world, climate, sea levels, movement of species, and mixing of biotic communities. These are all spinning fast towards a future that is hard to predict. Ecologists and designers are our only real protection against the troubles ahead. We need you to work together. Don’t let us down.

Improving this relationship is going to take some time. I can’t promise a happy ending, of course, but ask you to remember three things: First, your goals for a sustainable, healthy landscape are parallel, not divergent. Keep that in mind when you seem to have momentary troubles communicating. Second, you are both driven to improve the landscape, not watch it continually degrade; remember you’re soul mates, at least in that way. Third, we live in a rapidly changing world, climate, sea levels, movement of species, and mixing of biotic communities. These are all spinning fast towards a future that is hard to predict. Ecologists and designers are our only real protection against the troubles ahead. We need you to work together. Don’t let us down.

Shining a bright light on this underwater world is Heartbeats in the Muck, John Waldman’s terrific book about the teeming life below the surface and the environmental history of this most urban estuary. Having read the original shortly after it was published in 1999, I recently picked up the Revised 2012 edition. Dr. Waldman’s stories of how life in the Harbor survives and even thrives despite a variety of environmental insults are still poignant.

Shining a bright light on this underwater world is Heartbeats in the Muck, John Waldman’s terrific book about the teeming life below the surface and the environmental history of this most urban estuary. Having read the original shortly after it was published in 1999, I recently picked up the Revised 2012 edition. Dr. Waldman’s stories of how life in the Harbor survives and even thrives despite a variety of environmental insults are still poignant.

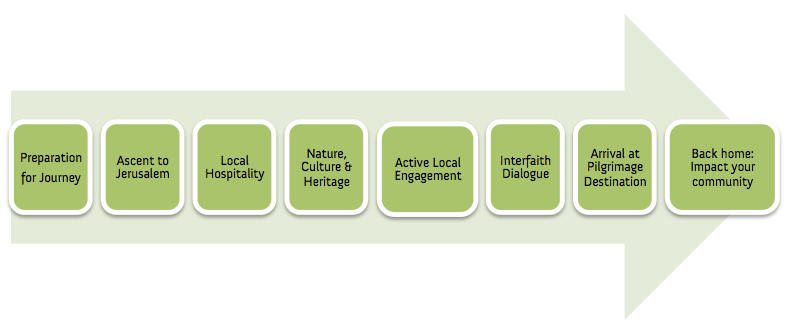

The beauty of the Green Pilgrim Ladder is its simplicity, while its special significance is that it places the burden of environmental responsibility on the shoulders of the traveller. The framework of travel starts in preparation for the journey, and we are asking the pilgrim not only to endeavor to leave a positive footprint on the way, but also to become a more responsible citizen in his or her own city after arriving home. Responsibility implies greater care for the environment, and greater respect for the many “others” in our neighborhood and throughout the public domain that we all share and enjoy.

The beauty of the Green Pilgrim Ladder is its simplicity, while its special significance is that it places the burden of environmental responsibility on the shoulders of the traveller. The framework of travel starts in preparation for the journey, and we are asking the pilgrim not only to endeavor to leave a positive footprint on the way, but also to become a more responsible citizen in his or her own city after arriving home. Responsibility implies greater care for the environment, and greater respect for the many “others” in our neighborhood and throughout the public domain that we all share and enjoy.

My friend Madhu Katti (also a TNOC writer) has written about other invasions of urban habitat by wildlife in recent times, including the return of the

My friend Madhu Katti (also a TNOC writer) has written about other invasions of urban habitat by wildlife in recent times, including the return of the

There was an international outcry; people protested on the street outside the building. The Audubon Society became involved and an out-of-court agreement resulted in a new engineered-nest being installed. Maybe because of the trauma, the pair failed to hatch any new eyasses following the disturbance of their original nest. “Pale Male: New York’s Most Famous Red-Tailed Hawk May be A Father Again’” declared ABC News in on May 20, 2011. After years in which Pale Male and his mate Lola produced broods of eyasses, Pale Male took up with a new mate Ginger at his Fifth Avenue address. Pale Male’s seventh and eighth mates were Zena and Octavia. In recent years many more red-tailed hawks have taken up residency in New York City and it is not an uncommon sight to see a hawk flying overhead in a city park. Apparently it is still common practice, however, to poison rats and pigeons and this leads to the unintentional death of raptors, like the red-tailed hawk, which prey on these lower food chain animals.

There was an international outcry; people protested on the street outside the building. The Audubon Society became involved and an out-of-court agreement resulted in a new engineered-nest being installed. Maybe because of the trauma, the pair failed to hatch any new eyasses following the disturbance of their original nest. “Pale Male: New York’s Most Famous Red-Tailed Hawk May be A Father Again’” declared ABC News in on May 20, 2011. After years in which Pale Male and his mate Lola produced broods of eyasses, Pale Male took up with a new mate Ginger at his Fifth Avenue address. Pale Male’s seventh and eighth mates were Zena and Octavia. In recent years many more red-tailed hawks have taken up residency in New York City and it is not an uncommon sight to see a hawk flying overhead in a city park. Apparently it is still common practice, however, to poison rats and pigeons and this leads to the unintentional death of raptors, like the red-tailed hawk, which prey on these lower food chain animals.

2 Comments

Join our conversation