Introduction

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

“How do you feel when something beautiful and priceless has been defaced?” asked the climate activist after throwing food on an iconic painting.

The “something” to which the activist referred was the Earth itself.

We have been talking about climate change for a long time now — the recent climate COP in Egypt was, what?, the 27th edition —but still progress, if you can call it that, is excruciatingly slow. We are running out of time.

Is science not enough to convince people to act? It seems not. One-hundred year storms every three years? Nope. 250,000 extra deaths and health costs of $US2-4B a year (an estimate from the WHO)? Not enough. Millions of climate-displaced people? Not even that.

So, what will spur action? Recently some climate activitists have taken to gluing themselves to or throwing food on famous paintings. There have been quite a few examples. Several activists were recently fined. (Apparentely no paintings have been seriously damaged yet.) “The adults aren’t listening”, say many young people, and it is hard to say they are wrong. But some new research in the United States suggests that people are indifferent to or slightly turned off by disruptive protests. Museums curators are upset, saying the the activist don’t know how fragile the works are, and museums are places of dialogue (which somehow seems to miss the point).

Are such shock tactics useful? Can they change opinion (in either direction)? Are they directed at the wrong targets? This is a prompt that asks us to reflect on the value of contentious and activist dialogue at intersection of art, science, ecology, activism, cities, and public opinion. A common theme among many of the responses included here — across the YESs, MAYBE, and NOs — is a deep exasperation at our failure to move climate action forward. One thread is that such activism aims at the wrong target. Another is that, well, it may be absurd, but at least it gets people talking about climate change. (Or does it?)

The prompt for the roundtable was “Are shock tactics such as defacing famous art useful?” For the record, this group, a mixture of artists, scientists, and practitioners (not a scientific sample!), votes like this:

Yes: 12

Maybe: 12

No: 8

I don’t know: 1

There is no consensus here, which is consistent with the hands-in-the-air exasperation most of us feel. Glue yourself to a van Gogh? Why not? Nothing else works.

Banner image: “Politicians discussing climate change”, Montreal, Canada (2015), by Isaac Cordal. It seems to capture the state of play fairly well.

Nea Pakarinen

about the writer

Nea Pakarinen

Nea is interested in how social interaction and tailored communication can affect our behaviors, specifically in the context of sustainable transitions. She has a M.Sc. in Sustainable Development, and has studied international journalism, marketing and communications. Nea has worked at the International Trade Centre Ethical Fashion Initiative, European Centre in Infectious Disease Prevention Control and ICLEI – a network of sustainable cities and towns, in development, media and communications roles.

The message from the activists is loud and clear: nothing is sacred if we are treating our planet like trash. Rings true right?

Yes – albeit my initial reaction upon seeing the news was what has Van Gogh done to deserve this? Why not choose a Picasso instead? But one has to admit the stunts are effective. People are growing immune to the effects of the barrage of climate doom and gloom in the news – and this made headlines far and wide. Further, the action ruffled the feathers of the high art circles who thought they might not have to deal with the climate change debate. Like in the ending of the movie ‘Don’t Look Up’ (spoiler alert) after the asteroid that everyone ignores (climate change) destroys the whole planet human artifacts float lost in space, as nothing more than detritus ― all of their imbued meaning lost without their host. “Attacking” timeless and classic art is poignant as we are running out of time. Note I will now talk of the young and the old, in very generalised terms ― there are exceptions! The younger generations are getting tired and cannot comprehend the resistance to change among the older generations. Slow and steady here does not win the race. I would expect this to be the spark for more drastic acts of ecoterrorism. Is throwing tomato soup or gluing oneself to art the most productive path for change? No, but I understand the frustration and desperation watching endless COPs and IPCC reports go by without drastic actions. Change when one is comfortable is difficult, and many affluent western nations and certain generations are just that. The previous generations feel like they worked hard for this wealth, prosperity, and power ― they did not expect the carpet being swiped out below their carefully built foundation at this stage in their lives. As we get past a certain age there is the expectation that things will become more settled and that we get to reap the benefits of our hard work. One can empathise with the resistance to having been told that what you strived for was wrong, your lifestyle damaging, and you need to change now now now! However, much of this striving for stableness ― or shall we say staleness, comes from the desire to ignore the inevitable ― death. People want to lull themselves into a false security as they age to avoid the unavoidable. But the thing is ― change is the only constant. We would do better as a species acknowledging this and embracing the other side of life, maybe by acknowledging how fleeting and precious our time is, we would treat things as more sacred. So what do I think a more productive path is to address climate change? Dialogue, understanding, and empathy. Incremental and persistent small changes reverberate into bigger transformations. But shock tactics do not hurt (we hope) either.

The message from the activists is loud and clear: nothing is sacred if we are treating our planet like trash. Rings true right?

Marcus Collier

about the writer

Marcus Collier

Marcus is a sustainability scientist and his research covers a wide range of human-environment interconnectivity, environmental risk and resilience, transdisciplinary methodologies and novel ecosystems.

To deliberately damage art as a form of protest seems misinformed and doomed to backfire as the cynicism takes hold. But here we are, talking about it now and even though there is still a lot of cynicism, dramatic acts grab attention.

Yes.

In the early 1980’s, when I was an undergrad, a huge environmental issue on our campus was ‘acid rain’. Acid rain is brought about by industrial emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOX) and sulphur dioxide (SO2) carried and deposited across borders. This often results in large-scale fish die-off in lakes far from where the emissions originated. The resulting international transboundary emissions agreements have largely taken acid rain off the agenda but, in my university at the time, no such agreements were in place and some students got very concerned. To raise concern, several prominent students took to wearing motorcycle helmets all day in order to indicate the deadly threat of acid rain. Even though acid rainfall does not cause injury to human heads like a motorcycle crash would, a subtle parallel was being drawn. But it was too subtle. The wearing of motorcycle helmets by non-bikers was viewed by other students as indicative of misinformed ‘activists’ ― just a bit silly. Acid rain was, and still is, a serious environmental issue, and indicative of a transboundary issue that can impact regions disproportionately. Making a dramatic visual statement seemed to be a good idea, but if it is too subtle then it is doomed to failure and even ridicule. Cynicism can be a hard barrier to break.

At the same time in the early 1980’s we did not yet use the phrase ‘climate change’, rather we spoke of ‘global warming’ ― a phrase that was not at all accepted or understood, and for many (especially in cold, rainy Ireland) it was something to look forward to, perhaps! Some of us tried to draw attention to the potential future perils of global warming. However, we were mindful of the unfortunate helmet wearers, so we tried desperately to find a new way to make our protests: something symbolic, something dramatic. But all we could manage were some loud marches with a lot of placard waving, and then some lecture picketing and distribution of information pamphlets. Predictable results: no media coverage, no policymakers meeting us to discuss our concerns, no debates in government, no protest songs, nothing. This was very frustrating, and for many it still is. However, as desperate as we were to make our point, we would never, in a million years, have considered damaging art to make our protest. Art is a sacred cow, an untouchable, something that is universally appreciated and respected, even if not understood. To deliberately damage art as a form of protest seems, as with the helmet wearers, misinformed and doomed to backfire as the cynicism takes hold. But here we are, talking about it now and even though there is still a lot of cynicism, dramatic acts grab attention. So, this overtly extreme form of protest has achieved its purpose in drawing public and media attention to the climate issue, as well as driving more people to visit galleries, but… where to go from here?

Robin Lasser

about the writer

Robin Lasser

Robin Lasser produces photographs, sound, video, site-specific installations and public art dealing with environmental and social justice issues.

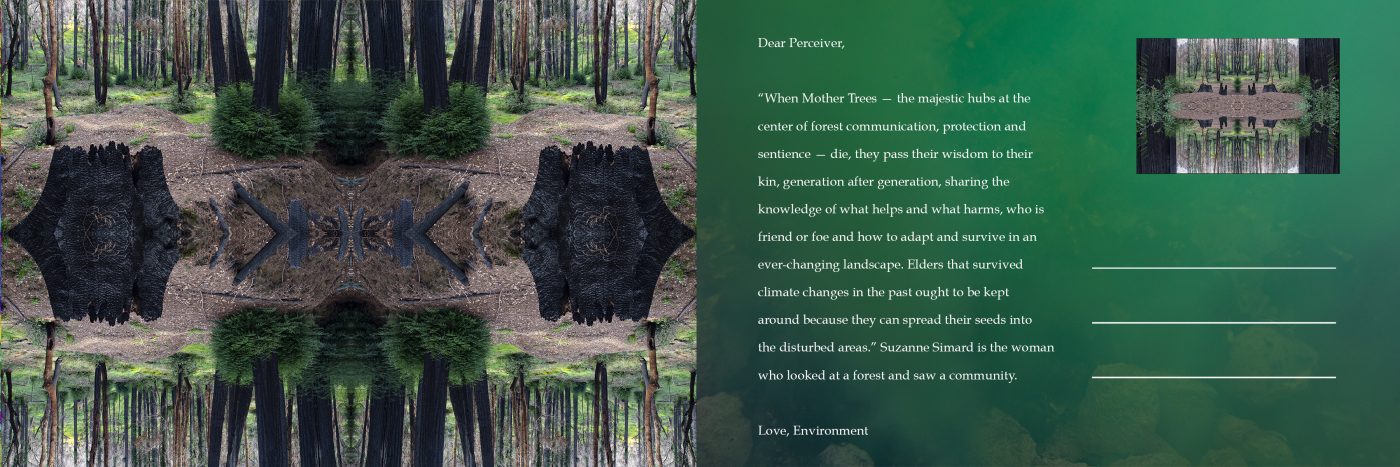

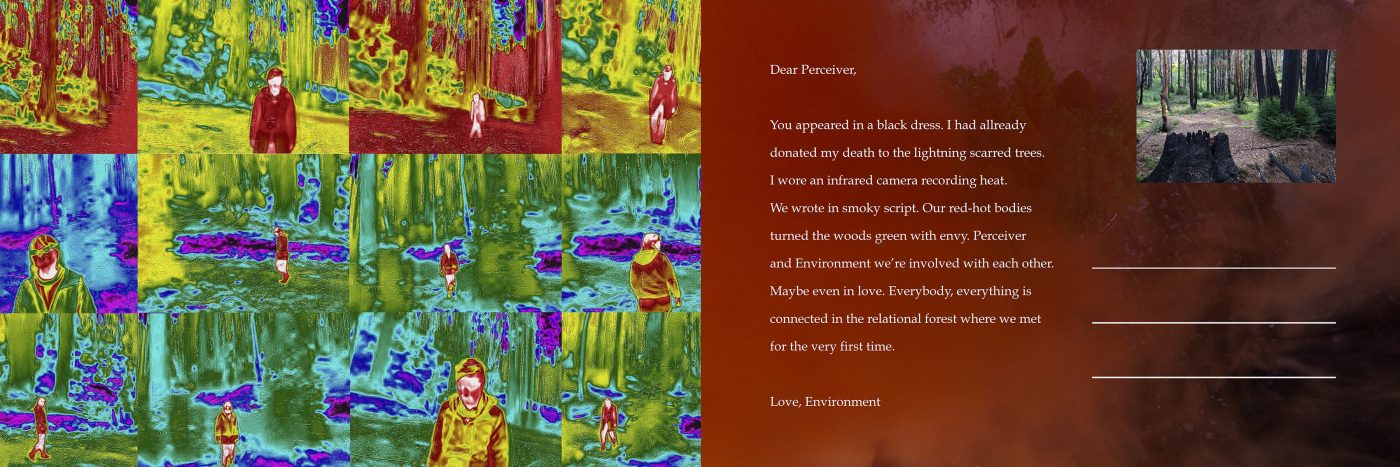

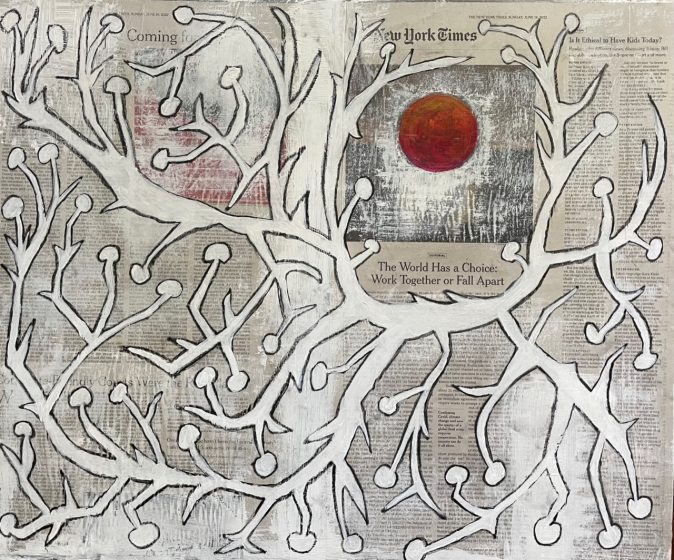

Trees Talk: They May Save US If We Listen

I don’t consider shock or violence a sustainable, engaging, or empathic strategy for anything, including societal transformation regarding climate change. Perhaps investigating our connections to everything ― living and dead, regional, and galactic ― has a chance of inspiring sacrifice, and love has a chance of engendering action.

NO

I don’t consider shock or violence a sustainable, engaging, or empathic strategy for anything, including societal transformation regarding climate change. Perhaps investigating our connections to everything ― living and dead, regional, and galactic ― has a chance of inspiring sacrifice, and love has a chance of engendering action. Immediate ventures require personal sacrifice for the health of our planet and all who experience this place as home. “Our house is on fire,” thank you Greta Thunberg for asking us, “what will we do?” Our children are rightly outraged by climate change, and the havoc my generation creates. Do we expect our children to clean up our mess? If not, who will? Perhaps the trees and their cooperative underground communication systems may offer a viable clue as nature struggles to adapt to a warming world.

Do violent acts, metaphorical or otherwise, targeting artworks inspire social change, movement, action? Let us consider the burning of books by the Nazis or the 2001 destruction of the two giant Buddhas in Bamiyan, Afghanistan by the Taliban. Are these acts of cultural violence an effective way to achieve cultural transformation?

Consider more recently, the actions of Wynn Bruce, a climate activist who set himself on fire in the plaza of the United States Supreme Court Building in Washington D.C. This act of self-sacrifice reflects the depth of his conviction that the value of an individual life is negligible compared to the havoc we are irrevocably bringing to our planet. This act of ultimate sacrifice carries a different weight than throwing soup on an iconic artwork, created by a male western Caucasian artist.

What call and response do such actions provoke in your nervous system?

Personally, I take refuge, wisdom, and inspiration from the trees. When the single organism vast aspen grove is threatened in any way, vital messages must be transmitted through a cryptic underground fungal network; interconnections to help sustain the health and vitality of the collective organism. These signals have evolved in unique and highly specialized ways so that subtle but effective messages move efficiently among highly interconnected trees, and cue appropriate defense responses. This network is pervasive throughout the entire forest floor, connecting all the trees in a constellation of tree hubs and fungal links. “The most shocking aspect of this pattern is that it has similarities with our own human brains. In it the old and young are perceiving, communicating, and responding to one another by emitting chemical signals…. It is enough to make one pause, take a deep breath, and contemplate the social nature of the forest and how this is critical for evolution. The fungal network seems to wire the trees for fitness. These old trees are mothering their children.” (Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest)

Damage from global warming represents the culmination of decades of rampant industrialization throughout the world and any effort to slow or reverse this condition will require a shared global recognition of cause and effect and a highly integrated and organic transcultural messaging system much like the communication system nature has provided the aspen grove. The trees offer wisdom, and they may save us, if we listen.

Do these museum interventions align with this challenge?

M’Lisa Colbert

about the writer

M'Lisa Colbert

M’Lisa Lee Colbert is a social scientist, and an urban farmer. She is currently working to improve access to locally grown produce year-round at an affordable price, in Montreal.

I believe we are in a state of emergency, and we live in a world where capturing audiences and increasingly short attention spans seem to be the only way to gain some momentum around an issue. So, why not glue yourself to a Van Gogh?

Maybe. It might be helpful. Similar acts of protest like road-blocking pipeline installations and inhabiting vacant buildings until the city accepts your communities’ bid over the condo developer’s bid are all forms of protest that have been proven to work. The difference is that those were attached to real carefully strategized goals ― there was a plan that made taking that risk a useful contribution and a small step for the wider cause. In the case of this painting and other incidents like this, I worry they risk setting the cause back by trivializing it. I had trouble formulating my thoughts on this one, so I hashed this out with my family over the recent holiday. I believe we are in a state of emergency, and we live in a world where capturing audiences and increasingly short attention spans seem to be the only way to gain some momentum around an issue. So, why not glue yourself to a Van Gogh? As my mother said, it’s not his fault his paintings are so famous and expensive. He died penniless and in relative obscurity like a lot of great artists do. My sister said that at the end of the day it’s a performative act, and not meant to be ‘real action’, you’re preaching to the choir basically. My father’s take was one where he thinks good energy is being wasted. He’d like to see all those youth just run for office and go where they need to go to get the job done. Imagine if you had Senators and Bureaucrats who cared enough about climate change, they’d glue themselves to paintings, in our governments!? I think seeing things like this makes me more sad than thrilled. Climate change got more attention, but it’s a debased kind of attention. It’s disingenuous, fleeting, and ego-ridden. I have no doubt that the passion and the urgency are real in the person committing these acts, but I disagree with the outlet. Do something real to solve the problem you are worried about. In the process of the doing and getting your hands dirty ― whether you’re tree planting, working to indict companies skipping out on environmental assessments, teaching kids in a classroom, or painting the beautiful landscapes we all stand to lose ― you’ll find more solace, bravery, and good energy to do more, in actually working towards the change you want to see. As my mother said, don’t resort to destruction because something is being destroyed. Grow, create, regenerate, or re-build something, among many other more helpful options. So, I don’t agree that gluing yourself to a Van Gogh is helpful, but I think acts of protest that may obstruct or destroy may be useful tactics, but it depends on the context. Lastly, on the level of personal growth for these kids who did the gluing, I think this experience probably helped them grow, if not the cause directly. It takes guts to subvert standing orders and normalized accepted behaviour (even if we are just talking about museum etiquette), if that’s channeled somewhere meaningful, it could lead to something really inspiring one day!

Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro

about the writer

Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro

Stéphane Verlet Bottéro (b. 1987) is an artist working at the intersection of social practice, installation, education, writing, gardening, and cooking. He is interested in the entanglements of community, materiality, body, and place. Based on site-specific research and durational interventions, his practice seeks to open spaces to unlearn and unsettle ways of inhabiting the world.

At the crossroads of institutional critique, action painting, and happenings, there is a performativity of the gesture that is carefully thought through: a new protest sport that blurs art and life (or rather, extinction).

Maybe.

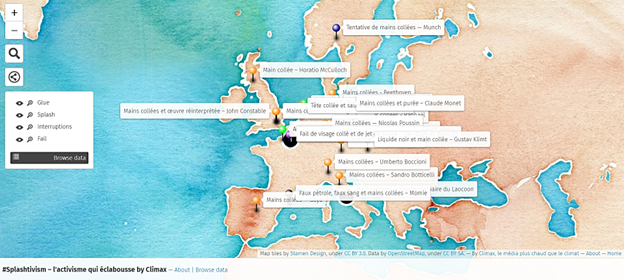

Much has been said already about the efficiency, symbolism, and aesthetics of climate activists’ spectacular throwing of soup, puree, oil, flour, ink, glue, at artworks that are all somewhat iconic of western modernity ― from Constable’s pre-industrial revolution, bucolic Hay Wain to Warhol’s fossil fuel-infatuated BMW Art Car. At the crossroads of institutional critique, action painting, and happenings, there is a performativity of the gesture that is carefully thought through: a new protest sport that blurs art and life (or rather, extinction). Most of these actions took place at museums that safeguard a eurocentric history of art and, consequently, of how art and environmental history mutually inform each other.

Commenting from Paris, I haven’t read in the French media and art criticism microcosm, any reference to another striking militant gesture by Congolese activist Emery Mwazulu Diyabanza, who in 2020 attempted to liberate and exfiltrate a 19th ritual pole from Chad out of the Quai Branly museum. A French equivalent to the British Museum, Quai Branly is located a few steps away from the Eiffel tower, another symbol of European industrial power, and was chosen by Diyabanza and his partners for its emblematic role in the debate on colonial theft and the restitution of African heritage.

Putting these gestures in dialogue would have seemed obvious, but the refusal to make the connection is not really surprising. In the North, most white middle-class ecologists who can afford to get arrested, tend to reproduce the totalizing view of the Anthropocene human/nature binary that silences not only its continuous relation to slavery and imperialism but also the practices and resistance of people subjected to them in the South. Little is done, in environmental movements and media, to connect the race to save the Earth with the struggle to repair the scars of colonialism. Malcom Ferdinand has coined the concept of double fracture ― environmental and colonial ― of modernity, to discuss how such silencing reinforces imperialist domination on plural ways of inhabiting the world sustainably.

In the Report on the restitution of African cultural heritage, Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr argue that nothing can replace what has been unrooted and compensate for the colonizers’ crimes; however, restitution of artworks and artifacts can operate at a symbolic level to start fixing the relationship that was broken. Environmental repairing must face the racial premises of capitalist extraction and rethink the claim to a habitable planet through the radical lens of restitution.

As long as climate actions refer to the museum as a white affair, the possibility to interpret them remains stuck on one side of history. If, beyond the pragmatic imperatives of urgency and spectacle, these initiatives seek to engage more closely and consistently with anti-colonial activists who also use the museum as a site of expression and contestation, I believe we really have a chance to overcome history and open spaces where the restoration of planetary relationships can truly begin.

Cecilia Polacow Herzog

about the writer

Cecilia Herzog

Cecilia Polacow Herzog is an urban landscape planner, retired professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. She is an activist, being one of the pioneers to advocate to apply science into real urban planning, projects, and interventions to increase biodiversity and ecosystem services in Brazilian cities.

On one hand, I love art and am shocked by this “vandalism”. On the other, I know that the message of the critical situation our civilization is now, is not reaching the public.

Maybe. The activists who are harming unique artworks, trying to call attention to the systemic planetary emergency that is impacting societies and the biosphere, are driving attention around the world. I am not sure what I think about those actions. On one hand, I love art and am shocked by this “vandalism”. On the other, I know that the message of the critical situation our civilization is in now is not reaching the public. As what has happened for decades with scientists’ alerts based on robust knowledge. I don’t think these attacks on famous paintings are effective for the intended target. In fact, they call it one-day news attention, and that’s it… Luckily the artworks have not been severely damaged.

Our civilization has surpassed some planetary boundaries and the speed to exceed others is evident. The system is too powerful and destructive and needs to keep the unsustainable growth myth that supports capitalism. Businesses as usual have been greenwashed to seduce consumers, no structural change has been effectively done yet. The consumerism and advertisement are guiding most people’s choices in the direction of self-destruction, accumulating monetary wealth in the hands of very few families. At the same time, having half of humanity out of the game, but those don’t count toward the market… Actually, they are part of the humanitarian crisis that is the other side of the coin of the predator capitalist system… The poor people did not cause the climate crisis, but they are the ones who suffer the most.

At the opening of the COP27, António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations, gave a serious alarm stating: “We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator.” Although I believe everyone should do what is possible to take their foot off the accelerator, I doubt that the extreme activists’ behavior will have a real long-lasting effect to contribute to the urgent transition that humanity must do.

Art is a powerful means of inspiration and provokes emotional, personal changes. That’s what an unaccountable number of artists have been doing. They are engaged in illuminating unseen critical ecological and social issues. They have gained worldwide visibility, using their talents to get the message to the public in a constructive manner, such as Yann-Arthus Bertrand, Sebastião Salgado, Mary Mattingly, Dr. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Olafur Eliasson, Doug Aitken, Nicole Dextras, Vik Muniz, among so many others. Several museums, cultural, and art centers have been promoting exhibitions to raise awareness about the pressing ecological and social issues. The approach of inspiring change, using art to make people feel how we could have better cities in harmony with nature and ourselves, is another way to make the public have a vision of a better present and future, that’s how Patrick Lydon works. I love his approach.

I believe real change comes from the people, with so many examples around the world, but needs real articulation. There is a need to overcome denial, diversion, and divide, as Michael E. Mann writes in the seminal book: The New Climate War.

I hope that the empowerment of new wiser leaders, young and historically excluded people, will enable a turn in the economic system. A paradigm shift is undergoing, forests and biomes are being intrinsically valued for the benefits they bring to the planet and humanity. In this process, the artists have been front-runners to call attention to the urgent ecological and humanitarian challenges. I believe nature-based solutions are the emerging transformation that will enable the rise of a nature-positive economy, an ecological economy.

Baixo Ribeiro

about the writer

Baixo Ribeiro

Baixo is President of the Choque Cultural gallery in São Paulo.

The climate urgency really calls for more radical solutions to get people’s attention.

Yes and no.

The climate urgency really calls for more radical solutions to get people’s attention. In fact, the population has not been sensitized by the scientists’ warnings and time is passing without the world reacting to the height of the urgency. That said, the attitude of the activists who threw food at historical paintings seemed, at first, something valid: after all, it really caught the attention of many people and caused reflections on the urgency. However, the repetition of this same type of action ends up causing the opposite effect: it creates dislike for the movement represented by the activists and for actions in favor of climate awareness.

Cathel Hutchison

about the writer

Cathel Hutchison

I am a socio-ecologist committed to fostering wilder places and spaces for nature, as well as better connecting urban and rural areas. I am also a climate activist who has engaged in my fair share of disruptive actions – one of my favourites can be found here.

It is precisely because of the significant power differentials that exist between activists and climate-wrecking corporations and their compliant governmental allies, that we need to embrace a diversity of strategies and tactics, as well as work together with a rich mosaic of activists and perspectives.

YES.

Disruptive tactics are necessary.

When employed effectively, they can act to challenge and destabilize entrenched power and expose injustice. Indeed, it is precisely because of the significant power differentials that exist between activists and climate-wrecking corporations and their compliant governmental allies, that we need to embrace a diversity of strategies and tactics, as well as work together with a rich mosaic of activists and perspectives.

In this way, I find myself more or less supporting recent attention-grabbing actions by Just Stop Oil (JSO) activists, including the infamous spraying of tomato soup on Van Gogh’s Sunflower painting in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Indeed, while I think I was more amused than anything else by the action itself, I feel their exposure of the disparity in the value assigned to ‘nature’ and particular officially-sanctioned cultural objects ― described as ‘priceless’, but effectively meaning they would sell for a very high price ― is both timely and necessary.

I have visited some of the most celebrated galleries in the world ― including the Prado in Madrid, Hermitage in St Petersburg, and the Museum of Pre-Columbian Arts in Santiago, Chile. Many of the famous artistic pieces they house are undoubtedly products of both cultural and individual genius, and their preservation and display are a source of great pleasure to millions. Nevertheless, the value and privilege assigned to some of these cultural objects, often enact a highly unequal, racist, and even speciest approach to preservation.

Beyond Cheap Nature

Part of this relates to the unspoken understanding that nature is or else should be cheap. In spite of the fact that the value of nature is increasingly acknowledged by a whole spectrum of actors ― from politicians, to developers, and the public at large ― the prevalence of a ‘cheap nature’ mentality remains widespread. It manifests in a lack of available funding for the maintenance of many city parks, even while they provide health and well-being benefits to thousands; a lack of official recognition given to urban wildlife on vacant and derelict land, even while these can be some of the richest sources of biodiversity in cities; and the extraordinary efforts that local activists must pursue to protect even the most highly designated protected areas from the flimsiest development proposals.

While increasing public access to and recognition of nature is essential, there needs to be a much more nuanced conversation about how and what we reciprocate to other species. Part of the challenge here is that the domineering neoliberal model of development constantly looks to narrow the field of responsibilities, including to other species, and increase opportunities for exploitation to monetary gain. Against this, regulation that mitigates the worst effects of this exploitation ultimately comes up short. This is exemplified in the fact that, in spite of genuine advances in the understanding of urban wildlife and the formulation of pro-wildlife policy, the most significant impacts of cities on wildlife remains poorly addressed – namely their ecological impacts through their global material and energy supply chains.

Returning to JSO’s tomato soup attack, it clearly ruffled some feathers in the UK press and generated heated condemnation and support. Was it merely performative? Maybe, maybe not. Activists like BP or Not BP have quite effectively employed disruptive tactics to force galleries such as the National Portrait Gallery to drop their fossil fuel sponsorship. Perhaps this desecration of an officially sanctioned artistic piece ― in consonance with attacks on colonial statues by Black Lives Matter activists ― can be understood as an escalation tactic in the ongoing conflict between an elite cultural regime and those who would see it take true account of its costs?

Peter Schoonmaker

about the writer

Peter Schoonmaker

Peter Schoonmaker leads the outdoor education program at American Community School Beirut, and is president of Illahee, a non-profit organization focused on designing new models for cooperative environmental/social/economic problem solving.

So far, everything that climate activists have tried has failed to slow our global economic juggernaut. Doesn’t mean they shouldn’t keep trying. But art destruction looks like a dead end. Why? Four Reasons.

Is defacing art helpful in climate activism?

Sadly, no. But not much else is either. Scientists and policymakers have been aware of climate change since the 1950s. And the general public has been well-enough informed about environmental issues since at least the first Earth Day, if not earlier (see A Silent Spring 1962, A Sand County Almanac 1949, Man and Nature 1849, and many others).

We have done plenty of “awareness building.” And it has led to a heartening level of “climate action” in terms of policy change, innovation, and implementation. At local, regional, and national in international scales. Renewable portfolios, take-back laws, efficiency standards, green planning, and sustainable farming are among the many actions we’ve taken to address climate change.

The problem is, it’s not enough. Not even close.

Why? Because the primary driver of climate change is a shared human delusion where we decouple the long-term, large-scale consequences of global economic growth from personal benefits that accrue from that growth in three broad categories: cost, comfort, and convenience. Wealthy nations and their citizens are unwilling to negotiate those three categories in a meaningful way, while less wealthy countries look to get in on the action by optimizing their own “three C’s,” which to them looks a lot like survival.

Climate activists are understandably frustrated that, after twenty-seven UN Climate Change Conferences in the last three decades, concrete, enforceable climate commitments linked to actual performance are, um, elusive.

I understand the frustration. As someone who followed Amory Lovins as an undergraduate in the 1970s, did my first climate change research in the 1980s, worked in the environmental field for decades, and suffered blow-hard business-as-usual incrementalists masquerading as “innovators,” I’ve LIVED that frustration.

So, I’m open to new approaches. I’m open to rattling a few cages. But so far, everything that climate activists have tried has failed to slow our global economic juggernaut. Doesn’t mean they shouldn’t keep trying. But art destruction looks like a dead end. Why? Four reasons.

First, doing bad things to art (destroying, defacing, appropriation, theft) puts you in pretty bad company, whether it’s the Taliban and Isis destroying statues and temples, the British Museum (Elgin Marbles), World War II Germany, or the various criminals who have smashed and grabbed works by Rembrandt, Raphael, Munch, and on and on). Do climate activists really want to be part of that club?

Second, destroying art to make a point doesn’t actually win friends and influence people. Don’t believe me? Ask the Taliban after they blew up the Bamiyan Buddas in 2001, or Isis after they leveled the temples of Bal Shamin and Bel in Palmyra in 2015. Okay, raising awareness to save the planet is not the same as imposing religious dogma. But the point stands. Find me a case of art destruction that changed attitudes and enlightened minds.

Third, defacing priceless art has a diffuse (small) public impact because of the ever-churning news cycle, briefly garnering the attention of a public that likely runs the spectrum from a few “approvers” to more “it’s sad they felt the need to do that, but I get it” to maybe more “these activists are nuts.” And then everyone moves on; attention moment over.

And finally, art attacks miss the crucial audience: powerful, wealthy decision-makers. If you want to influence this latter group, you have to threaten the things they truly care about. You think that’s art and culture? Think again, it’s power and wealth. The divestment movement has tried this with some, but not enough, success.

So, climate activists, you want impact? Look for high-impact, systemic, enduring, cage-rattling strategies. Defacing art isn’t one of them.

Bibi Calderaro

about the writer

Bibi Calderaro

Bibi Calderaro is a transdisciplinarian who weaves research, theories and practices from art, education, technology and ecology, blending diverse knowledge fields. Her work circulates internationally since 1995 aiming to build ecological solidarity within and beyond the human.

Although I do not advocate for violence, if shock is what puts the violence of Climate Change on the front page for a while, then I’d rather have shock.

Yes.

“…The truth is that no human endeavor can succeed on a planet beset by catastrophic climate change. None of our values, joys, or relationships can prosper on an overheated planet. There will be no “winners” in a business- as-usual scenario: Even wealthy elites are reliant on stable ecosystems, agriculture, and a functioning global civilization…”1

These are Margaret Klein Salamon’s words, the young psychologist behind the Climate Emergency Movement (CEM), one strategic thinker and funder backing the last wave of shock climate activism. Salamon’s research gives historical context to CEM’s logic. Their theory of change and strategizing are based on the fact that anthropogenic climate warming is not only not under control, but it is getting worse. CEM claims that Climate Change (CC) needs to be made the priority #1 for all governments and people alike and proposes a WWII-scale veering of all societal endeavors toward climate action―no more emissions and drawdown.2 Prioritizing this ‘emergency mode’ is what might halt CC in 10 years of full-on, dedicated work. Historically, this mode can also orient individuals to set aside their egos and willingness to thrive on their own and create a sense of community that works toward a shared goal―climate action.

I reached Salamon’s name by navigating a few key global newspapers where this last wave of shock activism made their front page for a while, after which inflation, the midterms, COP27, etc. took center stage in unconnected-loop-mode-as-usual. In another report from the same coverage, I read Aileen Getty― “The unfortunate truth is that our planet has no protective glass covering.”3 Despite my reticence to quote the daughter of a fossil fuel magnate, I admit that the resources and attention they draw are much needed and done quite “softly” — their language, far from radical, does not alienate.

So, should a piece of art ‘suffer’ to get the message across at a huge scale and fast pace? Activists were actually careful to glue themselves to art with glass protection, and suffering is one characteristic that has been extended to the more-than-human in the latest ontological turn, but artworks have not yet reached the set of suffering beings.4 One can also extrapolate without much imagination and predict that any piece of art along with whole collections will “suffer” a tremendous amount when the museums that house them and protect them for the enjoyment of the public5 become flooded by sea level rise, something that will occur in major coastal cities if governments do not make zero emissions and drawdown their #1 priority, now. Along with the museums and the artwork, those who are suffering CC are the public in general who, depending on where they live, are already feeling the immense repercussions of CC denial and greed.

My reflections on this inquiry as an artist, researcher, and educator for climate action are multiple, as they should be. Dr. Salamon is more convincing than most politicians, and activists are the only ones risking it all now so that life on the planet continues. Also, behaviors that engage ‘business as usual’ from all fronts of society are not just denialist, they are plain suicidal as individual response, but genocidal and biocidal―so, criminal and violent―on the part of governments. Violence has that complexity about it―never plain, straightforward, or immediate. It is layered, reciprocal, and, although I do not advocate for violence, if shock is what puts the violence of Climate Change on the front page for a while, then I’d rather have shock.

1 https://margaretkleinsalamon.medium.com/leading-the-public-into-emergency-mode-b96740475b8f

2 This means no more fossil fuel licenses and the capture of carbon at an expedited rate.

3 Aileen Getty; https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/oct/22/just-stop-oil-van-gogh-national-gallery-aileen-getty

4 On the contrary and historically it is artists who have suffered and also struggled to make art popular. The “artworld” instead is still an elitist space for the circulation of art and in this sense supportive of the “status quo.”

5 I am here quoting some museum directors in the same coverage of this news.

Marina Alberti

about the writer

Marina Alberti

Marina Alberti is Professor of Urban Design and Planning and Director of the Urban Ecology Research Lab at the University of Washington. Her research focuses on complexity, resilience, and eco-evolutionary dynamics in urban ecosystems.

Art as a Force that Changes the World: Why a New Imagination is Necessary to Draw Attention to the Climate Crisis

Activism can change the world only if its forms reflect its values. Activism wins when it is creative, not destructive.

My answer to your question: I don’t know!

What I know is that the image of two climate activists defacing a painting was hard to watch, it was a punch to my stomach, upsetting, and hard to understand. All that I believe in and all that I love put against each other. Activism can change the world only if its forms reflect its values. Activism wins when it is creative, not destructive. Symbolically the action did not make sense. There is something that the Earth and art have in common, they do not have a monetary value. Historically, art has been a form of protest. Why target art?

I say I do not know, rather than NO simply because I am trying to suspend my judgment and understand the action, beyond my emotional response. I do not condemn the form of protest per se. Each of us has a different perspective as to what form of protest we are willing to engage in and consider acceptable or effective, from civil disobedience to guerrilla warfare. But why against art? I know that the intention was not destructive, but the symbolic action was. Besides my emotional response, I have been asking myself whether the form of protest and its justification, the choice of targeting art reflects a cultural bias, a vision of what generates change that is of one community of the global north. How do people from other cultures relate to the image of climate change activists placing their survival to climate change against art? How would people of a future generation judge such action?

Climate change and protecting the Earth’s future are global problems. The urgency and scale of transformative action that addressing climate change will require are beyond what movements have ever experienced before. They call for a new global activism that connects places, cultures, and generations. Protest will need to engage a diversity of actors, expand its imagination, and speak a diversity of languages. Creating a global, pluralistic movement is not a trivial task. Protest is a multidimensional phenomenon that reflects the complex interplay between society, history, and culture. To be effective, the forms of activism that we choose to fight climate change as the solutions that we propose require a global, intercultural, and intergenerational perspective. They require imagining a future where humans and the planet cooperate. As a universal language and catalyst for transformation, art has the power to change the world and create a better future for both people and the planet.

Krystal Mack

about the writer

Krystal C. Mack

Krystal C. Mack is a self-taught designer and artist using her social practice to highlight food and nature’s role in collective healing, empowerment, and decolonization. Through comestible and social design, Krystal seeks to publicly unpack and heal personal traumas relevant to her lived experience as a disabled Black woman.

When science needs a little boost to really get folks on board, everyone knows shock value protests are always a great move.

Yes.

No, science is not enough.

We learned this during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even with a substantial amount of science around social distancing, masking, and vaccination, many people still ignore the researched and proven facts presented to them, even when their lives and loved ones’ lives are at stake, science can at times be not enough or even too much to believe in.

So, when science needs a little boost to really get folks on board, everyone knows shock value protests are always a great move.

Actually, I think they’ve been scientifically proven to be a great move, but you know how fake science can be…

But I do believe that shock value protests are useful up to a point.

They can bring attention (positive or negative) to an issue.

They can create opportunities for public discourse around protest strategy.

And these types of protests could help folks think critically about the effects of climate change and how they’re present in our lives today.

The Just Stop Oil activists succeeded in their more immediate goal to spread their message of ending our global reliance on oil.

But when it comes to getting those in power to end their dependence on oil?

There isn’t enough science or art in the world.

Nancy Grimm

about the writer

Nancy Grimm

Nancy B. Grimm is an ecologist studying interactions of climate change, human activities, resilience, and biogeochemical processes in urban and stream ecosystems. Grimm was founding director of the Central Arizona–Phoenix LTER, co-directed the Urban Resilience to Extremes Sustainability Research Network, and now co-directs the NATURA and ESSA networks, all focused on solving problems of the Anthropocene, especially in cities. Grimm was President of the Ecological Society of America (ESA) and is a Fellow of AAAS, AGU, ESA, SFS, and a member of the NAS. She has made >200 contributions to the scientific literature with colleagues and students.

Defacing famous art draws attention to the act, not the crisis, and centers on the activist, not the reason for the activism.

No.

Yes, I am frustrated that insufficient action is being taken to avert the climate crisis in the face of overwhelming evidence of its current and future impacts. Yes, I feel helpless against a power structure that seems continually to be all talk, no action. Our opportunities as individual citizens to influence policy seem to be too few and too weak to meet the urgency of the problem. As a scientist, I work on the impacts of climate change and strategies for adaptation and resilience and co-create future visions that can help steer cities toward meaningful actions. I worry that this too is insufficient and has little influence.

Yet, actions intended to incur shock and dismay to draw attention to the crisis are not effective. First, we must consider who the audience is. Museum visitors likely view the activists as eccentric and radical, and the press latches on to their actions as outlandish stunts that are newsworthy for their weirdness. The outrageousness allows those who really need to hear the message to ignore it as fringe behavior. In effect, these actions can marginalize all climate activism.

And the analogy doesn’t transfer well. “How do you feel when something beautiful and priceless has been defaced?”, asked when comparing precious art to the precious Earth, is probably more apt as an analogy for countless other global changes, such as land transformation wrought by mining and industrial agriculture, or modification of shorelines, rivers, and water bodies. Global-warming impacts manifest through more unseen, though certainly deadly, changes like increases in severity or frequency of storms, sea-level rise, extinctions due to phenological mismatches, or extreme heat events that put people’s lives at risk.

Climate scientist Katherine Hayhoe has been a vocal advocate for talking about climate change—in our homes and workplaces, with our friends and colleagues. The logic for this strategy is that a sea change in mass sentiment is needed, which can be a powerful driver of policy change. Talking about climate change is something that everyone can do. Would shock climate activism get climate conversations started? Perhaps. But the conversations should instead center on why and how to change our lifestyles, and how to elevate the rank of climate change among “issues we care about” above that of the economy or the price of gasoline, how we can effectively lobby for change with our pocketbooks and our votes.

Defacing famous art draws attention to the act, not the crisis, and centers on the activist, not the reason for the activism. There are more and better ways to support policies to mitigate climate change and to strengthen local capacity for resilience and adaptation in support of climate equity and justice.

Ania Upstill

about the writer

Ania Upstill

Ania Upstill (they/them) is a queer and non-binary performer, director, theatre maker, teaching artist and clown. A graduate of the Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theatre (Professional Training Program), Ania’s recent work celebrates LGBTQIA+ artists with a focus on gender diversity.

I don’t think this can be done effectively with scientific knowledge alone but instead needs to be combined with an artistic approach that appeals to our senses, to our love of humanity and its accomplishments, and encourages an appreciation of our place in the global ecosystem.

Maybe. I think these actions can be valuable for raising attention, but I don’t know how helpful they will be in the long run. There’s a part of me that loves the actions these climate activists are taking ― especially given that these paintings are protected with glass and are in no danger of being destroyed. The tactics are certainly effective at raising awareness ― I’ve seen more coverage of climate activism recently than I have for a long time. Part of that is the shock value. The images of iconic paintings with food spread across them are certainly striking. There’s an audacity that’s difficult to ignore. Who would dare deface the Mona Lisa, the most famous painting in the world?

So why my doubt? I question the assumptions these activists are making about their audience. The most obvious is that most, or all, people agree that the Earth is beautiful and priceless. I certainly agree, and I find the metaphor moving and powerful. Sadly, I’m not convinced that everyone agrees with this premise, nor am I convinced that defacing artwork will change anyone’s mind about the intrinsic value of the Earth. Another assumption is that simply raising awareness of climate change and environmental degradation will either a) spur greater overall public action or b) inspire world leaders to take faster action. But I’m not sure anyone who doesn’t already agree will be convinced by a metaphor, no matter how elegant or moving. I love humans, but we are slow to change our minds or actions, and when we do it is usually in response to something directly related to our lives, and in which we have a stake. While climate change does, or will, affect all of us, we have a hard time envisioning exactly how or what those impacts will be, and we can’t fathom actions we could take to prevent it. A strong call to action is powerful. What I find most powerful about my work with Theatre of the Oppressed is that our shows are framed to practice actions in the world to advance social justice. We show the problem, and the audience tries out solutions. The actions are concrete, and so are the outcomes. Adding a metaphor to a call to action (‘the painting is the Earth’) doesn’t necessarily make action feel more urgent or more achievable.

I also wouldn’t be surprised if public opinion is against them. These actions could encourage people to believe that climate activists are insane; that they are destructive; and that they are selfishly promoting their beliefs at the expense of others’ enjoyment of precious cultural artifacts. I don’t think we want to set up a scenario where we give more ammunition to the idea that we must choose between human culture and pleasure (art) and the natural world (the Earth). I believe better effects will come from actions that encourage people to see themselves as a part of the Earth and to build an understanding of how we will all be affected by climate change. I don’t think this can be done effectively with scientific knowledge alone but instead needs to be combined with an artistic approach that appeals to our senses, to our love of humanity and its accomplishments, and encourages an appreciation of our place in the global ecosystem. For such actions, we need scientists to share their understanding of natural systems. We need artists to think outside the box and create something beautiful and affecting. We need activists to bring their boldness and passion. I’d love to see what we can all accomplish together.

Paul Downton

about the writer

Paul Downton

Writer, architect, urban evolutionary, founding convener of Urban Ecology Australia and a recognised ‘ecocity pioneer’. Paul has championed ecological cities for years but has become disenchanted with how such a beautiful concept can be perverted and misinterpreted – ‘Neom’ anyone? Paul is nevertheless working on an artistic/publishing project with the working title ‘The Wild Cities’ coming soon to a crowd-funding site near you!

How Dare They!

The shock value of the glue and food/paint splatter has been enormous because we’ve evolved into a society that values artistic objects more than living landscapes.

Yes. The activist shock tactic of being glued to the frame of a Van Gogh is worth it and will eventually help change public opinion regarding action on climate change.

On one hand, you have the climate of an entire planet worsening daily and threatening the existence of billions of people, and on the other hand, as a means of drawing attention to this existential threat, you have some works of art being ritually threatened with damage which, at its worst, would mean the loss of monetary value of an object which is nominally worth millions of dollars to its owner but which brought little or no financial reward to the original artist.

The shock value of the glue and food/paint splatter has been enormous because we’ve evolved into a society that values artistic objects more than living landscapes. When a living landscape is threatened with destruction it is dismissed as the cost of doing business but when an art object is agreed to be financially valuable the idea of damaging it attracts international headlines. The activists effectively pretended to damage some works of art? How dare they!

The asymmetry of the ‘balance’ in that equation is utterly offensive. One side is about maintaining the conditions for all of us to be able to live on this planet, the other side is about protecting bank accounts.

It is remarkable that some works of art have phenomenal monetary value, but that value is negotiable and disputable. It is less a recognition of the value of the artists’ work and more to do with the commodification of creative ‘product’. In World War 2, the Nazis recognised the monetary value of the works of imagination they stole from Jewish owners, but regarded the living, breathing Jewish population of real people as worth less than nothing. Thus, Jews were dispensable, the art they owned was not.

The bizarre perversity in the way humans think about value is made worse by consumerist capitalism and its transactional approach to social relations. That perversity is at the heart of the glue-food-paint-splatter phenomenon, and it is why such activism is useful ― and inevitable.

The same forces are at play in the (ongoing) history of slavery in which human beings are reduced to commodities to be made into slaves whilst their lives as living, loving people are dismissed as irrelevant. The only reason to pay attention to a slave’s well-being was (is) to keep them alive and functional as a kind of exotic machine. Slaves needed to take extreme action to change the status quo, e.g., the 1831 Jamaica Slave Rebellion was brutally crushed but two years later the Slavery Abolition Act was passed (https://libcom.org/article/1831-jamaica-slave-rebellion). The slaves are complaining? How dare they!

The same forces were (are) at work in the movement for women’s liberation. Edwardian women were valued for what they could do to maintain the lives, status, and power of men provided they accepted the roles assigned to them by male society. When Emily Davison was killed trying to pin a scarf on the king’s horse in the middle of a major race (https://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/may/26/emily-davison-suffragette-death-derby-1913), her death was seen as tragic but her actions as indefensible. How dare she!

When civil society fails to deliver, and the legal system makes it ever harder to engage in peaceful demonstrations (as it is now in the UK, USA, and Australia), people can become remarkably uncivil and resort to violence. Or they can throw some paint to make a point. I’m with the art activists.

Sumetee Gajjar and Martin Rokitzki

about the writer

Sumetee Gajjar

Sumetee Pahwa Gajjar, PhD, is a Cape-Town based climate change professional who has contributed to scientific knowledge on transformative adaptation, climate justice, urban EbA and nature-based solutions. I currently work at the science-policy-research interface of climate change, biodiversity and vulnerability reduction, in the Global South. My research interests continue to be focused on urban sustainability transitions, through collaborative governance, just innovations and climate technologies.

about the writer

Martin Rokitzki

Martin is the founder and the current Managing Director of PlanAdapt, based in Freiburg, Germany. He heads and manages the PlanAdapt Coordination Hub. Martin also leads the continuous co-design and curation process behind the Climate Co-Adaptation Lab – PlanAdapt’s Collaboration and Innovation Platform.

Humankind, and especially those who have caused and continue to generate the highest levels of global emissions, unfortunately, do not care to see the links between their wealth, consumption practices, and the social and environmental predicaments other humans find themselves in.

Yes, it is helpful, in that it is an act that showcases the level of despair that some of us feel, and share. Humankind, and especially those who have caused and continue to generate the highest levels of global emissions, unfortunately, do not care to see the links between their wealth, consumption practices, and the social and environmental predicaments other humans find themselves in. We come from some of the highest emitting societies of the world (Germany, India, South Africa), and feel that ‘getting our priorities right is key’ and by now warm words are not enough. The intended audience of the climate activists who have been defacing “precious” works of art are the very privileged and powerful among us, who have enough wealth to own such works of art, and possibly the means as well to drive a recalibration of societal trajectories.

We understand that the intent of the climate activists was to deface famous works of art and glue themselves to the spot, in order for their frustration and anger to be heard since they could not be removed from the site of the ‘crime’. While the paintings were not actually damaged, the series of well-orchestrated acts of frustration have succeeded in creating a reaction, as evidenced in all the articles and comments about them, while earlier protests, science, and appeals have not solicited such a wide societal reaction, to date. The shock value of these tactics has spurred dialogue, debate, and polarisation in some cases, in places where privilege otherwise softens a scientifically-informed and locally-grounded response to the climate crisis.

Unfortunately, the actual beautiful and priceless “thing” that the paintings are meant to represent, the earth and all life on it, remains under existential threat and does not have a glass cover protecting it. It is a gift whose resources we have inherited and needs all of us to care for and protect it. Are we, as the carers of this planet, a world society and, between countries, able to manage a rights-based, peaceful transition / transformation process, with the necessary scale and speed? As an appropriate response to the current socio-economic and environmental crises facing humanity? Or are conflict and disruption (sometimes forcefully) needed? As disruptive as these acts have been, they are also reminiscent of the Chipko Andolan, whereby rural women in India clung onto trees that they did not want authorities to cut down. The defaced famous paintings serve the dual purpose of standing in for our precious planet, and for hurting the privileged, where it hurts.

Historically, it appears as if those in power are unwilling to redistribute power and wealth. In which case those among us, who are frustrated at the lack of action, believe the science that predicts large areas of the earth as becoming unliveable, well before the end of the century, due to the climate crisis, and see current practices culminating in further exacerbated biodiversity loss, will see sufficient cause to rebel. We will also find support among those of us who find our writing, research, and scientific endeavours failing to achieve the desired shifts toward transformational change. The risk is that it may not remain performative, which the recent acts by climate activists were. We are in an era of hard questions and challenges when tweaking around the edges will not be sufficient, to avoid doom and gloom.

These acts by the climate activists lead to the basic question:

What kind of action would the wealthy and powerful react to so that an agreed, consensus-based, peaceful transition / transformation process (at the necessary scale and speed), can be commenced? Such a rights-based process must incorporate the difficult task of redistribution of wealth (including dismantling the supremacy of private ownership of land and property rights) and the injustices associated with current agreements, whereby those who have contributed the least to climate change, suffer the most, and will continue to do more so in the future.

Christopher Kennedy

about the writer

Christopher Kennedy

Christopher Kennedy is the associate director at the Urban Systems Lab (The New School) and lecturer in the Parsons School of Design. Kennedy’s research focuses on understanding the socio-ecological benefits of spontaneous urban plant communities in NYC, and the role of civic engagement in developing new approaches to environmental stewardship and nature-based resilience.

Here’s the thing: the earth has already been so significantly “defaced” that I’m not quite sure we understand what shock or urgency looks like anymore. Or perhaps more importantly, how best to build empathy for the more-than-human world.

Maybe, but here’s the thing: the earth has already been so significantly “defaced” that I’m not quite sure we understand what shock or urgency looks like anymore. Or perhaps more importantly, how best to build empathy for the more-than-human world. Actions like the ones at Courtauld Gallery remind us that we do need to test the boundaries of what agitates and excites the imagination to confront a crisis of worldviews that seems unwilling to understand the true scope of our climate crisis. This leaves us with a persistent question: what kinds of art, science, or activism will actually connect with people and enable large-scale societal change? And how do we compete with the likes of TikTok and a media-rich escapist environment so pervasive in our culture today?

If we consider these acts from a research perspective, a study by Sommer and Klöckner (2021) might be helpful. Their research highlights how artworks that inspire novel solutions and offer a way for communities to participate are often more impactful than conventional methods (e.g., mainstream news media, and scientific reports). Why? Because they can elicit a personal and emotional connection, which scholars and media critics continue to emphasize are more effective than providing facts or employing scare tactics concerning impacts or risks.

Is the recent wave of ‘climate shocktivism’ able to accomplish this personal connection? Maybe not fully, but I think we need all the tools at our disposal. And that may very well include Deborian spectacles like the ones being produced by Just Stop Oil and other groups. However, if we really want to indeed inspire a systems-level change, then we also need something more entrenched in our everyday experiences. Something long-term that is both gradual and “in-your-face”. Interventions into the food system (supermarkets, farms), the energy system (your car and gas station), the social systems (schools and courts), and economic systems (your work and livelihood) for which we depend upon. And while many artists or activists make attempts to do this, and even propose new systems (see Ant Farm, Bonnie Sherk, Eve Mosher, Superflex, Future Farmers, etc.), it’s rare that these interventions manifest into the kind of change at the scale we need. Ultimately, art, science, or activism in isolation will never be effective or sufficient. What we need is a multiplicity of strategies alongside transglobal policy that calls for a fundamental rethinking of our fossil fuel-obsessed culture, and actually holds corporations and actors accountable.

A splash of paint and a glued hand may not deliver that to us ultimately. Nor will condemnation from the art world that merely labels these actions a “stunt”. Perhaps these, like Thunberg’s climate strike, are examples of actions we need to see and debate as we imagine new practices and acts of creative resistance. Ones that help us shift our worldviews away from a human-centered narrative toward one of mutual flourishing.

Pantea Karimi

about the writer

Pantea Karimi

Pantea Karimi is an Iranian-American multidisciplinary artist, researcher, and educator based in San Jose, California. Her art explores historic, religious, scientific, and political themes. Karimi utilizes virtual reality (VR), performative video, animation, sound, print, drawing, and installation.

To bring attention to climate change, we need more conversations, and more scientific facts to be shared through conferences, local community events, at schools by discussing it with youth, and through art exhibitions, which are focused on the subject to bring awareness.

How do you feel when something beautiful and priceless has been defaced?” asked the climate activist after throwing food on an iconic painting. The “something” the activist referred to was the Earth itself.

As an artist, I can’t justify seeing any artworks being attacked or ruined even for a good cause. It is wrong! Art for centuries has chronicled the earth story. Van Gogh’s Olive Trees picturing a hot climate warms our spirit, while Turner’s Stormy Sea chills our spine. These paintings tell the story of climate.

We have been talking about climate change for a long time now, but still, progress is slow, and we are running out of time. Is science not enough? Yes, science is enough for featuring facts, but it is not enough to reach the masses who are not avid readers or active listeners. It happens that it doesn’t reach everyone the same way. Science has to be simplified and accessible for non-scientists.

What will spur action? Recently some climate activists have taken to gluing themselves to or throwing food on famous paintings. (Apparently, no paintings have been seriously damaged yet.) Are such shock tactics useful? No! to me they are property and cultural acts of vandalism. To bring attention to climate change, we need more conversations, and more scientific facts to be shared through conferences, local community events, at schools by discussing it with youth, and through art exhibitions, which are focused on the subject to bring awareness. As an artist, I would like to see more collaborations among scientists, artists, and institutions where we can express issues and reach the masses.

Rob Pirani

about the writer

Rob Pirani

Robert Pirani is the program director for the New York-New Jersey Harbor & Estuary Program at the Hudson River Foundation. HEP is a collaboration of government, scientists and the civic sector that helps protect and restore the harbor’s waters and habitat.

Bold statements that our shared heritage is at stake, whether it is our art or our shared planet, remind us that business as usual is not really going to cut it.

Yes

But what makes public discourse?

Here is a scenario you might be familiar with: Your committee’s deliberations stretched past lunch and into the late hours of the afternoon. The group had run through the icebreakers, developed a theory of change, prioritized actions, brainstormed metrics, and was now considering next steps and assigning responsibilities. The excitement of the challenge and finding common understanding had faded. The uncertainty of knowledge, familiar disagreements, and the need for additional data, study, funding, and time loomed ahead.

No one expects that developing a collective response to climate change is easy. The imperative for action can easily run aground on the slow pace of developing scientific, technical, and political understanding and consensus.

But the imperative is there. It is sometimes easy for the scientists, planners, managers, and policymakers among us to lose sight of that during needed, but sometimes endless, deliberations.

The tragic consequences of extreme weather can impel action (and the availability of funding). But post-disaster decision-making is unlikely to lead to thoughtful responses. And once the disaster has left the headlines, people and politicians forget. Daily life resumes. And the will to make substantial, long-lasting, and effective change seems to fade as well.

Gluing one’s head to a painting is not a response to climate change. It’s just a cry for help. But political theatre and creative protests keep climate change and its consequences in the public eye and in the collective discourse. While muddling through our climate crises is perhaps inevitable, muddle we must. The only wrong thing to do is to stop trying to find answers.

Bold statements that our shared heritage is at stake, whether it is our art or our shared planet, remind us that business as usual is not really going to cut it.

Domenico Vito

about the writer

Domenico Vito

Domenico Vito, PhD engineer, works in European projects on air quality in Italy. He has been an observer of the Conferences of the Parties since 2015 – the year the Paris Agreement. Member of the Italian Society of Climate Sciences, he is active in various environmental networks and has been active participant in YOUNGO, the constituent of young people within the Framework Convention of Nations Unite.

No.

Such forms of action, besides being wasteful and damaging —and climate change is not about waste but about regeneration — can be very counter-effective for the climate movement.

Climate activism is one of the most important ways to participate in climate action. Anyway, even climate activism can turn into a “misuse” of the power it has. I will be clear I will not agree with such a way to pursue climate activism even if I can deeply understand the feelings inside who made it.

Such forms of action, besides being wasteful and damaging —and climate change is not about waste but about regeneration — can be very counter-effective for the climate movement. If street demonstrations have raised attention and brought the public opinion in favour of tackling climate crises, hitting culture and historical heritage can indeed move people away from sustaining climate activism and in final climate action.

So, even if I feel the emotion of who is lead to such action, in general, I will not feel to support them. Anyway, I take them as a signal of the discomfort civil society has towards a lack of ambition in current planetary governance.

Mitchell Pavao-Zuckerman

about the writer

Mitchell Pavao-Zuckerman

Dr. Mitchell Pavao-Zuckerman is an Associate Professor at the University of Maryland. He is an ecologist studying the interactions of decision making, design, and environmental change on ecosystem processes in urban landscapes.

Shock alone is not enough to change minds and make people act, but relationships between art, ecology, and activism can reframe how we see our planet and our place in it.

No.

These activists attempt to spur action by connecting climate change, art, and science, and, while they are right to make those links, they miss the mark.

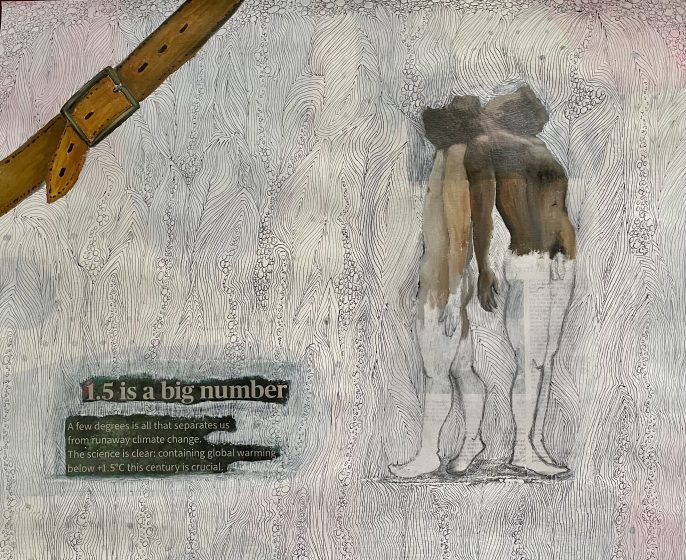

While we might also be tempted to say, ‘listen to the science!’ ― science and facts about climate change alone are not enough to motivate action. People understand our planet is changing. Headlines constantly show the increasing role climate change is playing in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events like drought, floods, heatwaves, and fires. Motivating people to act on climate change is more a matter of communication. We already have enough facts and know enough about climate change. So, people in general already know about climate change ― as Just Stop Oil themselves recognize, “it’s not even about raising awareness now, it’s about demanding action.” If that is the case, what role can art take in raising awareness of climate change?

People may have trouble connecting with the global scale of climate change and need some local touchstone to help make that global scale more intimate. The environmental writer Mitchell Thomashow suggests that personal links between art and science, such as keeping a nature journal, would help us observe changes around us over time, changes in places we are emotionally connected to ― this could motivate people to act by connecting them to a planetary scale change.

On the recent art protests, eco-philosopher Tim Morton said, “that’s the point of [the soup protest], to make everything suddenly uncanny…deliberately or not, to stop people and make them see things differently.” Art itself can do that too. Protestors and activists can cut out the middleman and seek out collaborations with artists and scientists. We could flip the conversation and see how the art itself can be an intervention, a tactical innovation, and a form of protest to raise awareness of climate change, help build coalitions, and spur people to action. Shock alone is not enough to change minds and make people act, but relationships between art, ecology, and activism can reframe how we see our planet and our place in it.

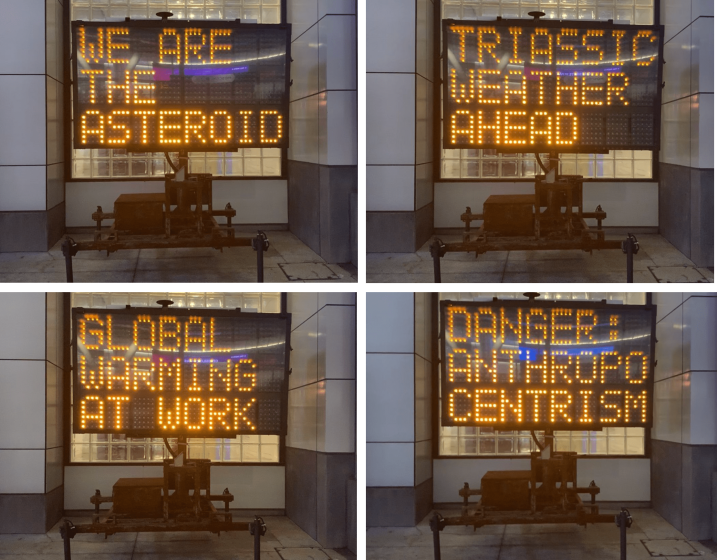

A great example of this is a work of art that is a collaboration between the artists Justin Brice Guariglia and Tim Morton, titled, We Are the Asteroid. In this piece, an electronic construction message sign is altered to display a set of ‘eco-haikus’. These messages are jarring and disruptive (just like throwing soup on a painting). These messages make things uncanny and in doing so, make us see things differently. We reconceptualize our place and role ― equivalent to a cosmic event ― framed within a warning sign that is common in our urban spaces. Throwing soup might be shocking and uncanny (pun intended?) ― but it seems to make people angry and not necessarily see themselves and their relationship with the Earth differently.

The performative nature of the recent art protests (no paintings were harmed in the making of this protest) is shocking, but not enough to help us reframe our relationship with nature and act urgently to meet the challenges we face.

References

Thomashow, M. 2001. Bringing the biosphere home. MIT Press.

Patrick Lydon

about the writer

Patrick M. Lydon

An American ecological writer and artist based in East Asia, Patrick uses story and community-based actions to help us rediscover our roles as ecological beings. He writes a weekly column called The Possible City, and is an arts editor here at The Nature of Cities.

I dig punk rock, and throwing soup at art is a nice punk rock try. What we need now, are more compelling stories, not about the world we currently inhabit, but about the world we want to inhabit, and how we can get there.

Maybe it is a start.

Does context matter?

Some thirty years ago, the artist Ai Weiwei painted the Coca-Cola logo onto a 2,000-year-old urn. A few years later, he broke two such ancient vases on purpose, photographing the act. The images became an artwork known as Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn. Most of the international art community hailed these as ‘brilliant’ works of art.

When asked why he dropped the 2,000-year-old vases, Weiwei commented that “Chairman Mao used to tell us that we can only build a new world if we destroy the old one.”

Could Mao’s instructions help us today? Maybe ‘destroying’ old social values is a bit extreme. But one could hardly argue with the need to at least ‘let go’ of most of our aggressively anthropocentric value systems.

Can we let go?

Most humans actually want to. The wall between us and that ‘letting go’ in most cases, is simply the fact that we are afraid of not knowing where we’ll land after we have let go. This fear is understandable, and it seems to come mostly from our not having met the right stories—narratives of what a possible, equitable, regenerative world might look and feel like in our own corner of the world.

Does story matter?

One could argue that the thing which separates the current spat of climate activism from artworks like Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, is the absence of a cohesive story embedded into the act. Story is a necessity. For the whole of human history, so far as we know, story is the tool that has built our world, reminded us who we are, why we are here, and most importantly, what we value.

Our culture is a story. Things like currency, status, power, material wealth, science, the nuclear family, precious artworks. These are, all of them, cultural stories; viewpoints of how to see the world. There is no finite value, for instance, in a pile of paper with numbers on it, or in a blockchain of 1’s and 0’s. The value comes from a collective societal belief in a story. “Ah, money has value. Ah, this artwork is priceless.” These are all stories; epiphanies transcended into shared values through continued cycles of retelling and believing.

Is it wrong to value money or artwork more than we value human survival? I don’t know. What I do know is that money and art are both good examples of how the value system of our society works. Both offer compelling stories, and compelling stories work.

Our biggest issue in our inability to deal with climate change then, is not that we do not know how to solve it — both science and practice show that we do know how. The issue is that we have not yet written and/or shared enough good stories about the way forward, stories about the possible world that biologists, farmers, solar punks, sustainable urbanists, and others are trying to show us.

I dig punk rock and throwing soup at art is a nice punk rock try. What we need now, are more compelling stories, not about the world we currently inhabit, but about the world we want to inhabit, and how we can get there.