about the writer

Lindsay Campbell

Lindsay K. Campbell is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service. Her current research explores the dynamics of urban politics, stewardship, and sustainability policymaking.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

about the writer

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

Introduction

Do you have a word or phrase you use for socially-driven environmental care in your region? Tell us in the Comment section.

How do we describe or name these activities? How do we, across languages and cultures, express the idea of “actively taking care of things we care about, such as the environment”?

We are gathering personal accounts of people’s stewardship stories from all over the world: cherished memories, everyday occurrences, sparks that started social movements. We welcome your story.

This roundtable was inspired by our workshop “Talk, Map, Act” at the TNOC Summit where we gathered diverse stories of engagement with stewardship from all around the world.

We want to continue this journey by exploring the words people use for the constellation of activities suggested by the English word “stewardship”. We are interested to hear how the act of environmental care is expressed in different languages and contexts.

So, we asked 25 practitioners—scientists, activists, artists, planners, practitioners—from five continents: in your context and experience, what is the word or phrase used for the concept of “actively taking care of things, such as the environment”?

Visit here for other emerging TNOC Summit outputs.

What sort of multiple linguistic meanings are opened up by exploring how people describe the concept of “care for the environment”?

What sort of multiple linguistic meanings are opened up by exploring how people describe the concept of “care for the environment”?

In addition to thinking cross-culturally, how does the concept translate across urban to rural gradients?

What might thinking deeply about the meanings and limitations of expression of this concept tell us about the role of citizens and the state in our relationships with the biosphere?

[This Roundtable is a collaboration between The Nature of Cities and the USDA Forest Service, and is an output of The Nature of Cities Summit.]

about the writer

Emilio Fantin

Emilio Fantin is an artist working in Italy on multidisciplinary research. He teaches at the Politecnico, Architecture, University of Milan, and acts as coordinator of the “Osservatorio Public Art”.

Emilio Fantin

La Stewardship è una strategia di gestione responsabile che introduce un principio etico dell’uso delle risorse. (Stewardship is a responsible management strategy that introduces an ethical principle of resource use.)

“Stewardship,” una parola, molte applicazioni. Il termine anglosassone stewardship non è traducibile con un corrispettivo italiano, ma letteralmente significa: “gestione etica (responsabile) delle risorse”. Quali risorse? I beni comuni come l’acqua, il territorio, le foreste, la salute, le persone, i risparmi e i prodotti. (Stewardship, one word, many applications. The Anglo-Saxon term “stewardship” cannot be translated with an Italian equivalent, but it literally means: “ethical (responsible) management of resources”. Which resources? Common goods such as water, land, forests, health, people, savings and products.)

Stewardship is an ethic that embodies the responsible planning and management of resources. The concepts of stewardship can be applied to environment and nature, economics, health, property, information, theology, etc.

I have selected from the Net, three definitions of stewardship, two of them in Italian and one in English.

Only through an autonomous process of consciousness—suggested by the word stewardship—can we share the sacredness which lays behind human nature. It is not a matter of thinking about which future disasters will kill us, or whether we will destroy the entire planet, but rather a matter of acting on the true sense of our relationship with the existence of life around us.

These values are applied to the idea of good and more specifically, collectively speaking, of common good. Ethics (also known as moral philosophy) is the branch of philosophy which addresses to questions of morality. But terms such as “strategia di gestione” (management strategy) or management of resources sound to me like terms which do not belong to philosophy or morality humanistic sphere. There is a big discussion about language, because specific words can be related to concepts which assume different meanings from the original ones, especially when these words do not originate in their own field but they are imported from other cultural spheres.

That is the case with words like “management strategy”, which evidently come from both economic, business, and military lexicons. I know they are commonly used in many other disciplines, but that doesn’t mean that they are properly used. “Stewardship of resources”, from my point of view, has to do primary with the word “care”, which means love put love into practice. If we intend the meaning of the words “stewardship of resources” as the result of a strategy, or we think that it concerns a hierarchical management structure, we reduce it to an abstract concept and we significantly diminish the possibility of a positive result. By-taking care of resources, we intend to individually develop a profound relationship with all resources and common goods such as: water, air, green, food, human beings, soil or animals. It means to understand the essential quality of a particular status, form and way of being of all these elements, their esthetics and functions. It means to respect them in the same way we respect ourselves. That’s it. Because by taking care of them, we reconnect ourselves to a horizon which doesn’t comprehend finalized aims or strategic attitude but a true form of love.

A strong movement of transformation can take place whenever each part of a whole starts to act autonomously, instead of following a common direction or strategy. Only through an autonomous process of consciousness—suggested by the word stewardship—can we share the sacredness which lays behind human nature. It is not a matter of thinking about which future disasters will kill us, or if we will be able to destroy the entire planet, but rather a matter of discovering the true sense of our relationship with the existence of life around us.

about the writer

Kevin Lunzalu

Kevin Lunzalu is a young conservation leader from Nairobi, Kenya. Through his work, Lunzalu strives to strike a balance between environmental conservation and humanity. He strongly believes in the power of innovative youth-led solutions to drive the global sustainability agenda. Kevin is the country coordinator the Kenyan Youth Biodiversity Network.

Kevin Lunzalu

In day-to-day local applications, stewardship is also used to mean a guardian, a servant, and an agent. In rural villages where farming is predominant, farmers are regarded as stewards of their lands, farm animals, and produce.

Steward is also widely implied to a manager or person in charge. In local Swahili context, the term Msimamizi is in this case used, instead of Wakili. Good examples include Msimamizi wa hali ya hewa (air steward), Msimamizi wa duka (shop steward), and Msimamizi Mkuu (chief steward). In this regard, the steward is directly in charge and answerable to their respective areas of jurisdiction. Stewardship is also used to depict leadership.

As a largely religious country, Kenya’s faithfuls regularly use the term and execute stewardship in their contexts. In Christianity, for example, the Bible depicts Jesus Christ as the steward of the Church, with practical incidences in which He takes care of his flock and looks out for his lost sheep. Christians believe that Jesus is their leader, and they walk in His footsteps. In essence, the word “Christian” is a direct derivative of the term “Christ”, who is the Biblical head of the church. Furthermore, Christians are mandated to “Pro-create” and take care of all the creatures that God created. In Islam, Prophet Mohammed is another supreme being who is largely associated with the ethical stewardship and growth of the religion. Christians and Muslims in Kenya and by extension the world, are taught to live by the teachings of the Bible and the Quran, the respective Holy books that are expected to guide them.

In day-to-day local applications, stewardship is also used to mean a guardian, a servant, and an agent. In rural villages where farming is predominant, farmers are regarded as stewards of their lands, farm animals, and produce. On the other hand, in cities such as Nairobi, people are employed to take care of businesses, government and private property. Think of security officers, human resource managers, chefs, cleaners, gardeners, civil servants, and many other professions—they are all in-charge of a certain jurisdiction. In some cases, stewardship is also viewed as a specialization, with a certain level of understanding, professionalism, set of skills, experience, and abilities expected of the persons in question.

The mantle of stewardship can be passed down from one generation to another. In Maasai cultural setups in Kenya, sons are trained by their fathers on proper livestock techniques while mothers instill homestead management skills to their daughters. Since they are pastoralists, the Maasai people move with hundreds of heads of cattle from one place to another in search of pasture and water. The young boys are, in essence, taught proper stewardship of the cattle—livestock is a highly precious aspect of the family unit and a symbol of wealth. When they become of age, the young boys and girls are initiated into adulthood through a rite of passage in which they are taught how to take care of families and execute husband and wife duties responsibly. In more formal setups such as workplaces, handing over ceremonies depict the same aspect.

Stewardship elements also came out strongly in the olden Kenyan justice systems. Before colonization and subsequent independence that came with the current court systems, the commonly used traditional method of solving conflict and crime cases was through the jury system. In this case, the accused persons were presented before a council of elders who would listen to both the accused and the accuser, and in some cases witnesses, before making a final verdict on whether the person was guilty or innocent of the claims placed against them. The council of elders in this regard were stewards of the principles of the communities and guarded the moral values considered to be acceptable in society.

In ancient times, communities peacefully co-existed with nature. The Maasai and Ogiek people of Kenya are perfect examples, as their lives directly depended on the sustainability of forests and wildlife. While the Maasai exclusively practiced pastoralism and hunted wild animals for food, the Ogiek lived inside forests, depending directly on them for livelihood. This instilled a sense of conservation awakening and environmental stewardship. Well, until modern conservation happened.

about the writer

Lindsay Campbell

Lindsay K. Campbell is a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service. Her current research explores the dynamics of urban politics, stewardship, and sustainability policymaking.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

about the writer

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

Lindsay Campbell, Erika Svendsen, and Michelle Johnson

Stewardship is not the same as ownership—but it does mean taking ownership of your place, voice, and power in the world. We aim to show that all of us have a stake in caring for our local environments, whether we own any inch of ground or not.

Our work as Forest Service researchers at the NYC Urban Field Station has aimed to advance the scholarship and practice of urban environmental stewardship, with a focus on the role of civic groups. We understand stewardship to consist of both caretaking for and claims-making on the environment. Anyone can have a personal experience of being a steward through acts of hands-on work, engagement in advocacy, expressions of love, and transformation of systems—and we’ve begun gathering personal accounts of people’s stewardship stories from all over the world. These narratives range from cherished memories, to everyday occurrences, to sparks that started social movements. To add your own story to the map, go here!

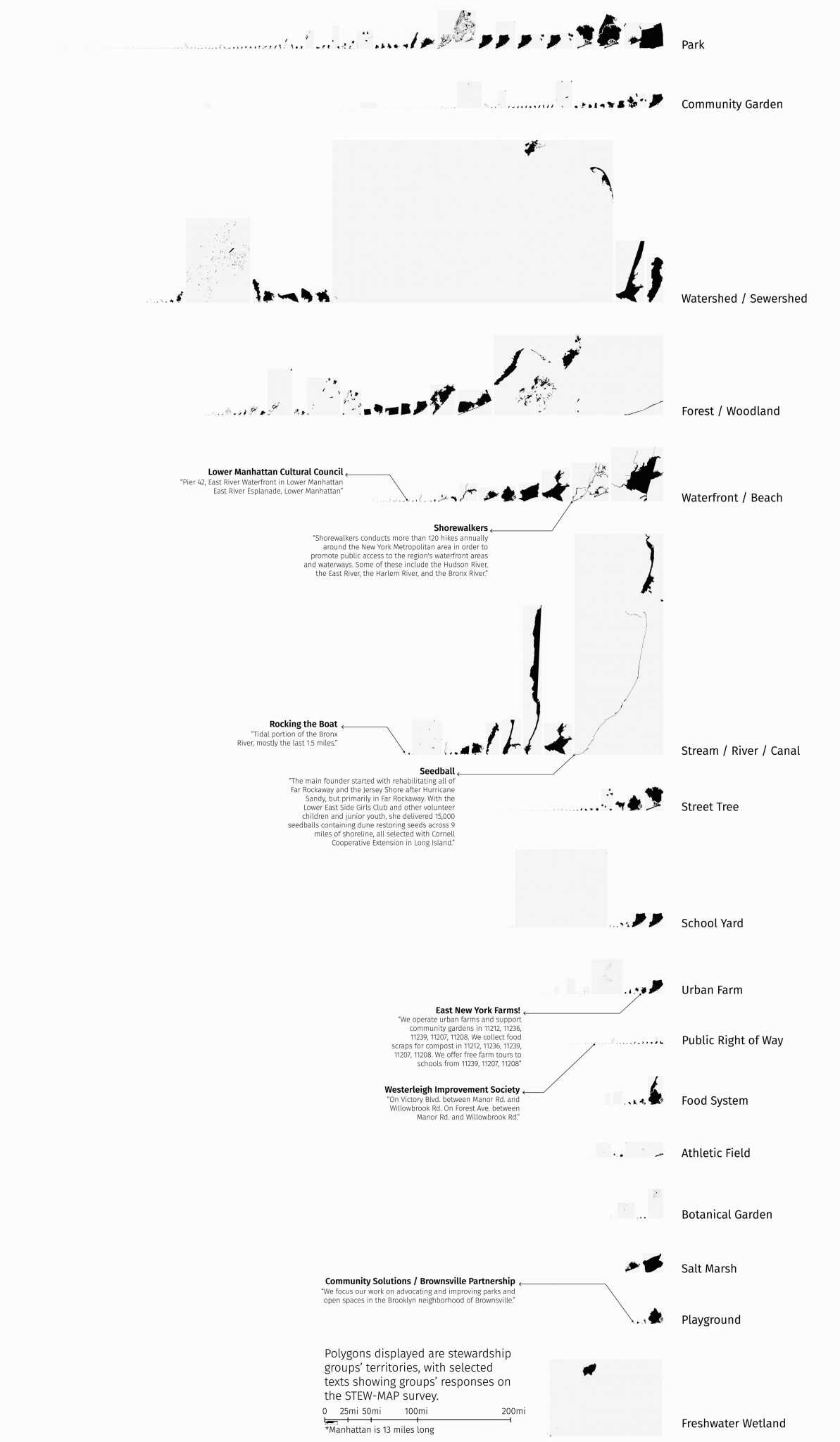

We have found that individuals rarely engage in stewardship alone—and often it takes the form of local civic engagement. Many stewardship groups start from a shared experience of friends or neighbors—out of a desire to improve a local community, restore something that was lost, or create something new. And there is incredible power in these civic groups, power that we have aimed to make more visible by mapping groups’ territories and networks through STEW-MAP.

Why a map? In our market-driven American society we have a finely honed sense of private property; public agencies have a clear sense of the lands that they manage and where their jurisdiction lies. But how do we visualize and map the role of the “third” sector, or the civic realm that also shapes so much of our governance and our green and grey environments? Stewardship is not the same as ownership—but it does mean taking ownership of your place, voice, and power in the world. And by mapping stewardship, we are attempting to level the playing field a bit—to show that all of us have a stake in caring for our local environments, whether we own any inch of ground or not.

about the writer

Carlo Gomez

Carlo is the Department Head of the City Environment and Natural Resources Office of Puerto Princesa City Government.

about the writer

Zorina Colasero

Zorina is Senior Environmental Management Specialist for the Puerto Princesa City Government.

about the writer

Romina Magtanong

Romina is an Environmental Management Specialist, and Supervising Officer of Balayong Park Urban Forestry Development Program of City ENRO.

Carlo Gomez, Zorina Colasero, and Romina Magtanong

The CommunityAct Program encourages the engagement of the community and other stakeholders in various tree planting and environmental activities and to be stewards of their environment. In the case of the City’s Balayong Park—also known as People’s Park—interested individuals and groups were given the opportunity to adopt Balayong Trees, and receive responsibilities and certificates for doing so.

“Stewardship” is one of the strategies/approaches used by the Philippine Government in managing the natural resources of the country. It is making the qualified interested group/individuals as partners in managing properly the particular timberland areas by giving them authority/permits through issuance of appropriate tenurial instrument such as Certificate of Stewardship Contract (CSC)—(individual/family), and Community-Based Forest Management Agreement (CBFMA) (community/peoples’ organization).

Awarding/issuance of tenurial instruments comes with responsibilities that the beneficiaries/stewards should do to ensure that the area and the resources within the awarded timberland are properly managed with the perception that they own it.

The City of Puerto Princesa conducted various tree planting and other environmental activities in the past, but it was observed that the participants of those activities just come and go and didn’t mind what happens next.

This is the main reason for conceptualizing CommunityAct Program. The Program encourages the engagement of the community and other stakeholders in various tree planting and environmental activities and to be STEWARDS of their environment.

On the other hand, i-Tree Tool, a tree inventory tool developed by US Forest Service to quantify ecosystem services provided by trees, promotes Stewardship since the tool can change how people value trees. People will not only value trees for the lumber they can provide but also for the ecosystem services as well. Such information will give them more reason to be stewards of the trees in their areas.

In the case of the City’s Balayong Park—also known as People’s Park, where “Stewardship” was first applied in tree planting and environmental activities—interested individuals and groups were given the opportunity and/or privilege to adopt Balayong Trees; they were given Stewardship Certificate as a proof of tree adoption.

As stewards of the Balayong trees they have planted, they have the responsibility to ensure that their adopted trees will survive and grow well. Stewardship develops sense of ownership to the trees they have adopted. In addition, STEW mapping activities in Balayong Park is on-going.

about the writer

Cecilia Herzog

Cecilia Polacow Herzog is an urban landscape planner, retired professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. She is an activist, being one of the pioneers to advocate to apply science into real urban planning, projects, and interventions to increase biodiversity and ecosystem services in Brazilian cities.

Cecilia Herzog

We need to be GUARDIANS, PROTECTORS and DEFENDERS in and out of the cities now. We must resist, all of us, for our common home: Planet Earth!

The words that I first thought of were “GUARDIÃO” (guardian), “PROTETOR” (protector), “DEFENSOR” (defender) of the forest, rivers, birds, trees, river springs, nature… Many public and private programs and projects use those names.

Public programs in Rio have helped to change the landscape since the mid 19th Century, when the Emperor D. Pedro II commissioned Major Archer to replant native and fruit trees in the hills of the city, aiming to restore water springs, offering numerous direct and indirect ecosystem services up to now. Actually the benefits were so great that the city is now an international UNESCO Heritage Site: “Rio de Janeiro: Carioca Landscapes between the Mountain and the Sea”. Following the same path, in early 1980”s a city program transformed many of the degraded slopes with collective tree plantings (Mutirão Reflorestamento). This is a term used to bring people together to stewardship nature in the city: MUTIRÃO.

In the last years in São Paulo, there have been numerous MUTIRÕES to plant “Pocket Forests”, “Community Gardens”, “Rivers Springs Restorations”, “Rain Gardens”. Those collective actions are usually led by residents.

In Rio de Janeiro and other cities many actions have also been happening, with residents working together to change gray paved surfaces into green areas, because people need nature where they are. They want to participate, get together and transform the harsh landscape into a livable one. We love to make it together.

In July I had a personal experience when I was engaged in the process of designing and implementing the first rain garden of the city in a famous cultural center in the downtown area: “Fundição Progresso“. I proposed to co-create and co-design it. We organized two workshops and collective plantings (mutirões) with Organicidade, the landscape architect Pierre-André Martin, and also with Celso Junius (a city server with decades of experience in urban greening), with full support of the “Fundição” and Bambuê (the architect company in charge of building the garden). I never thought that we would be named stewards of nature in the city, but that was exactly what we were doing. We depaved a “no-where” gray backyard, built an edible rain garden, with native Atlantic Forest fruit trees, non-conventional edible, medicinal and ritualistic plants. On 28 September 2019 the rain garden area was opened to the public in a wonderful event that turned the decades old cultural institution in the Green Fundição, that aims to connect culture, arts and nature. The ceremony brought indigenous people from tribes located faraway. There was so much symbolism to recover an area and praise Mother Nature back to the city with the original residents of our country, who have been under attack by the current Federal administration.

Actually, I believe that people steward nature, but in countries were millions are unemployed it is not a priority. The systematic destruction of the rich ecosystems that my country has is caused by the myopia of the economic system that only sees the economic value of what is under the forests, and the potential for economic growth on hard infrastructure destroying rivers and forests, with hydropower killing our rivers and culture and new roads crisscrossing protected areas. We need more than ever to be ashamed of this predatory vision of permanent growth and stewardship nature and indigenous people! We need to be GUARDIANS, PROTECTORS and DEFENDERS in and out of the cities now. We must resist, all of us, for our common home: Planet Earth!

about the writer

Xin Yu

Xin Yu (aka Fish) is Shenzhen Conservation Director and Youth Engagement Director of The Nature Conservancy China Program. Since 2017, he has overseen TNC’s first City project in Shenzhen, China, focusing on Sponge City

Xin Yu (aka Fish)

In China, “stewardship” seems to be a word related more to rural conservation, and its core idea of “taking care” embeds an emotional tie to the object, connecting to us equally. The relationship becomes much weaker and passive in an urban context.

My environmental NGO career has mostly taken place in urban China since 2006, previously as a campaigner in Beijing and then in Shenzhen as an urban conservationist with The Nature Conservancy. When I started thinking about “stewardship” in the Chinese language, I recalled that this word hasn’t been used much in my daily work in English communication. So, in order to help make sure my contribution brings broader understanding on the term, I asked several colleagues of mine who have worked much longer in rural China. Here is some interesting feedback I heard back.

Bob (Asia Pacific Cities Program Director): I remember having a discussion with TNC China staff about the meaning of stewardship almost 20 years ago. And it was used a lot in TNC in those days. For example, the old science department was called Science and Stewardship for many years. As I remember, the straight translation was “management” in Chinese, as in nature reserve management. That was the simplest way to translate it and I think that is what we mostly used. That’s my historical perspective.

Bo (Shanghai Conservation Director): I still remember the first time we met people from the Alliance for Water Stewardship, and I asked Bob what’s the meaning of stewardship. It was almost two years ago. After that, there has been no more chance to use the word with others. It is really a kind of challenge to give a nice and proper Chinese translation. Is this the same challenge for “city with nature” or “nature-based solution”?

Yue (Strategy & Planning Director): I think “stewardship” means two things in general: sustainable use and care. The specific translation for the term depends on the context. For instance, we usually say rangers carry out stewardship programs. In this case, it means 管护,management and protection. We also say environmental stewardship is everyone’s responsibility. In this case, it means 维护/保护, care/protection. We say the park has a citizen steward group, in this case, it means 守护, care/safeguard. Water stewardship should be in this category.

Lulu (Hong Kong Conservation Director): I personally understand stewardship as “to take care of something/some people/some place”. We often say at TNC we do our best to cultivate local stewardship by empowering local people, which is really to ensure people to take care of their natural environment after they understand the dependent relationship people have with nature.

* * *

It seems to me that “stewardship” is a word related more to rural conservation, and its core idea of “taking care” embeds an emotional tie to the object, such as land, water and wildlife. We think they are connecting to us equally, as if everyone has a share of them. Nevertheless, the relationship becomes much weaker and passive in an urban context. People do not easily carry a feeling of responsibility about the built environment because it is always with a legal possessor, e.g. developers take the land, rich people buy building units, greening space is under property management, parks are managed by a park service… Urban residents use the term “protection” more frequently due to the urgency of their built environment being damaged. But passionately taking care of something (assumedly) owned by another party? Hardly a common phenomenon of urban mentality in today’s China.

The subtle difference between wildness stewardship and environmental protection reveals an essential effort of my daily work. We keep trying not only to lift the importance of biodiversity in the city environment—people have yet to recognize it as a basic need—but also to cultivate or recapture a citizenship where everyone has a stake in their city.

about the writer

Nathalie Blanc

Nathalie Blanc works as a Research Director at the French National Center for Scientific Research. She is a pioneer of ecocriticism in France. Her recent book is Form, Art, and Environment: engaging in sustainability, by Routledge in 2016.

Nathalie Blanc

The good of my well-being is connected to the protection of irreplaceable beautiful environment. The good of my well-being is also connected to my participation in a common good, resisting public policies or human behavior that is destructive.

In this round table, I would like to propose extending the use of the term to much more ordinary forms of engagement in the environment, generally based on a lively sensitivity to the state of the latter, or even to not distinguish between the maintenance of human bodies in the environment and the health of this environment itself, modifying or even abandoning, thereby the use of the term “environment”.

The term “stewardship” is therefore likely to be based not only on a commitment to the environment, but also on the idea of its transformation. The objects created, the environments produced, the elements of nature reconfigured in the light of new perspectives, notably in terms of urban planning, are all potential indicators of a transformation of the environment and of people in time and space. In addition, taking care of the objects of the environment made sensitive, active for oneself and loved ones, so that they persist or that, at least, the value that one recognizes to them recurring, supposes to think about the modalities of factors of the environment, but also to the aesthetic and ethical theories that govern this care.

In fact, the aesthetic is crossed right through by the dimensions of the social and the cultural; it promotes, among other things, empathy, the recognition of a relationship between an environment and/or an object therein, and a feeling of pleasure, of self-recognition or of the collectives involved. One of the feelings that this relationship with others and the environment gives rise to is that of protection and the desire to reproduce its sources. These two desires and/or needs are related to the idea of ethics, which, as G. Agamben (2003) explains, is the sphere that knows neither fault nor responsibility, the sphere of the happy life. “Recognizing fault and responsibility is tantamount to leaving the sphere of ethics and entering into that of law”[i].

Engaging in stewardship projects requires us to recognize successes and failures in this area as well as life and death in the environment related to the free will of human beings. How to engage with and in the environment, invest fully, i. e. aesthetically, a living environment, to promote its image in the present and the future, is part of an ethics of “care”. Stewardship is about recognizing what is due to material and social vulnerabilities, the natural and cultural construct, the extraordinary beauties and violence of life, and the possibility of its disappearance. More simply, it is a question of highlighting—it is henceforth indispensable—elements of finiteness of human lives, animal and vegetal lives, of what they rely on to create life, in order to develop an ethic that integrates the environment as relational proximity, as being of the order of an objective concern. It is the impossibility of an overcoming in the manner humans know—that is to say, by the predation of other regions of the world, or other natural resources, or by the exhaustion of those present, or the extinction of a civilization. But an aesthetic reading of the environment predisposes to a prior concern, then corollary of the action towards it. It dramatically changes the perception of the environment’s agency; it creates new opportunities for relocating responsibility for what happens to it.

So, from an ethical point of view, we can’t deny the role of the environment in the sense of what surrounds us, or what the ecological question has produced in terms of a collective representation of the environment. The good of my well-being is identified in particular with the protection of this irreplaceable singularity that represents the beautiful object (or the beautiful environment)[ii] . The good of my well-being is also identified in the idea of participation in a common good in resistance also proactive and positive action to public policies or to human behavior that can be described as destructive. In this sense, the action to be taken is that exemplified by the good of my well-being in the continued adequacy to living conditions. Therefore we could use the word of « intendance » to translate stewardship but being related to nobility, it may raise suspicions, so we may as well behold on the english term.

* * *

Le bien de mon bien-être est lié à la protection d’un environnement d’une beauté irremplaçable. Le bien de mon bien-être est aussi lié à ma participation à un bien commun, à la résistance aux politiques publiques ou à un comportement humain destructeur.

J’aimerais, dans le cadre de cette table ronde, proposer d’élargir l’usage du terme à des formes beaucoup plus ordinaires d’engagement dans l’environnement, se fondant, généralement, sur une sensibilité vive à l’état de ce dernier, voire qui ne font pas de distinction entre le maintien des corps humains dans l’environnement et la santé de cet environnement lui-même, invalidant, de ce fait-même l’emploi du terme « environnement ».

Le terme de stewardship, dès lors, repose non seulement sur un engagement à l’égard de l’environnement, mais aussi sur l’idée de sa transformation. Les objets créés, les environnements produits, les éléments de nature reconfigurés à l’aune de nouvelles perspectives en matière d’aménagement ou d’urbanisme sont autant de signes annonciateurs d’une transformation des environnements et des individus et collectifs dans le temps et l’espace. En outre, prendre soin des objets de l’environnement rendu sensible, actif pour soi et des proches, afin qu’ils perdurent ou que, tout au moins, la valeur qu’on leur reconnaît se reproduise suppose de réfléchir aux modalités de fabrique de l’environnement, mais également aux théories esthétiques et éthiques qui gouvernent cette prise en charge. En effet, l’esthétique est traversée de part en part par les dimensions du social et de la culture ; elle promeut notamment l’empathie, la reconnaissance d’une relation entre un environnement et/ou un objet qui s’y trouve et un sentiment de plaisir, de reconnaissance de soi-même ou des collectifs impliqués. L’un des sentiments que fait naître cette relation à autrui et à l’environnement est celui de protection et de désir de reproduction de ce qui en est à l’origine. Ces deux désirs et/ ou besoins sont liés à l’idée d’éthique qui, comme l’explique G. Agamben (2003) est la sphère qui ne connaît ni faute, ni responsabilité, la sphère de la vie heureuse. « Reconnaître une faute et une responsabilité revient à quitter la sphère de l’éthique pour pénétrer dans celle du droit » [iii].

S’engager dans des projets d ‘«intendance» exige que nous reconnaissions les succès et échec en la matière ainsi que la vie et la mort dans l’environnement en lien avec le libre arbitre des êtres humains. En quoi s’engager dans l’environnement, investir pleinement, i. e. esthétiquement, un milieu de vie, en promouvoir l’image au présent et au futur, participe d’une éthique du « care », traduit par « soin » ou « attention », qui met l’accent sur le souci du proche et de la proximité, l’attention au singulier. Il s’agit de reconnaître ce qui est dû aux vulnérabilités matérielle et sociale, au construit naturel et culturel, aux beautés et violences extraordinaires de la vie, et à la possibilité de sa disparition. Plus simplement, il s’agit de mettre en évidence – c’est désormais indispensable – des éléments de finitude des vies humaines, des vies animales et végétales, de ce sur quoi elles s’appuient pour se créer une vie, afin de développer une éthique intégrant l’environnement comme proximité relationnelle, comme étant de l’ordre d’une préoccupation objective. C’est l’impossibilité d’un dépassement à la manière que nous connaissons, c’est-à-dire par la prédation d’autres régions du monde, ou d’autres ressources naturelles, ou par l’épuisement de celles présentes, ou l’extinction d’une civilisation.

Or la lecture esthétique de l’environnement prédispose à un souci préalable, puis corollaire de l’action à son égard ; elle change dramatiquement la perception de l’agentivité de ce dernier ; elle crée de nouvelles opportunités quant à la relocalisation des responsabilités quant à ce qui lui arrive. Donc, il ne peut être question du point de vue d’une éthique de méconnaître l’environnement, au sens de ce qui nous environne, ni même ce que ce que la question écologique a produit du point de vue d’une représentation collective de ce dernier. Le bien de mon bien-être s’identifie notamment à la protection de cette singularité irremplaçable que représente le bel objet (ou le bel environnement) [iv]. Le bien de mon bien-être s’identifie également dans l’idée de participation à un bien commun en résistance à des politiques publiques ou à des conduites humaines que l’on peut qualifier de déprédatrices. En ce sens, l’action à conduire est celle qu’exemplifie le bien de mon bien-être dans l’adéquation poursuivie à des conditions de vie. Par conséquent, nous pourrions utiliser le terme «intendance» pour traduire «stewardship» mais, étant lié à la noblesse, cela peut éveiller les soupçons. Nous pouvons donc aussi bien utiliser le terme anglais.

Notes:

[i] Agamben, G. (2003). Ce qui reste d’Auschwitz. Paris: Payot Rivages, 25.

[ii] Breviglieri, M., Trom, D. (2003). Troubles et tensions en milieu urbain. Les épreuves citadines et habitants de la ville. In D. Cefai et D. Pasquier (Eds), Le sens du public: Publics politiques et médiatiques (pp. 399-416). Paris: PUF.

[iii] Agamben, G. (2003). Ce qui reste d’Auschwitz. Paris: Payot Rivages, 25.

[iv] Breviglieri, M., Trom, D. (2003). Troubles et tensions en milieu urbain. Les épreuves citadines et habitants de la ville. In D. Cefai et D. Pasquier (Eds), Le sens du public: Publics politiques et médiatiques (pp. 399-416). Paris: PUF.

about the writer

Johan Enqvist

Johan Enqvist is a postdoctoral researcher affiliated with the African Climate and Development Initiative at University of Cape Town and Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University. He wants to know what makes people care.

Johan Enqvist

In Swedish, “Ta hand om” is a common phrase usually translated as “taking care of”; the literal meaning, is more like “taking in your hand”. “Ta hand om naturen” communicates both an individual responsibility to be careful with nature, but also the shared effort of joining hands to achieve in the interest of our co-dependency on nature.

Writing this text was surprisingly valuable to me, and taught me new things about something that I had spent five years of PhD research investigating. After dissecting three words that I thought would together cover the meaning of stewardship—a word with no direct translation in Swedish—I have ended up instead focusing on the expression that I best think captures the notion of “actively taking care of things we care about”.

First, three Swedish meanings of stewardship. Förvaltning generally means management or custodianship, caring for something valuable on behalf of someone else. Most often it is used to describe some part of Sweden’s public administration and bureaucracy, which is meant to run the country for the benefit of the population according to the elected government. Skötsel describes the more everyday activity of taking care of a piece of land, livestock, crops, machinery, or facilities, but also one’s own health or general conduct. The verb sköta version can also refer to temporarily caring for someone else’s children, household, or business interests, temporarily while they are unable to do so. Skötsel implies moral imperative or duty, and professionalism and expertise rather than care or compassion. Vård refers to a nursing kind of care, usually for someone or something (animate or inanimate) that is harmed, sick, aging or exhausted and needs to heal, recover, or receive palliative care. Vården is generally used to describe the health care sector as a whole. An older meaning is to watch over something, like a guard-post, beacon, monument, or a guardian spirits or angels.

None of these words explicitly refer to nature (natur) or the environment (miljö), but all can do so by adding prefixes: Miljöförvaltning is a common name for municipalities’ environmental departments; naturskötsel and miljövård typically refer to activities to maintain and restore natural systems. However, there is a sense of empowerment and bottom-up aspect of stewardship that is lacking in these terms; the commitment that comes from working with something you are personally invested in.

Ta hand om is a very common phrase usually translated as “taking care of”. The literal meaning, difficult to capture in English, is more like “taking in your hand” or “putting your hand around”. It carries notions both of taking responsibility, expressing care and compassion, and making things happen to achieve results. Ta hand om varandra, “look after each other”, is something you affectionately say to an older child left alone with younger siblings, a newlywed couple embarking on a new chapter, or dear friends that leave behind when moving abroad—especially if either party is particularly vulnerable or in need of healing. Ta hand om naturen communicates both an individual responsibility to be careful with nature, but also the shared effort of joining hands to achieve change (societal, behavioural, cultural) in the interest of our co-dependency on nature. Importantly, the idea of your hand directly applied to nature—even greeting it, “shaking its hand” as ta i hand translates to—also gives a sense of connectedness, of embodied care as opposed to the bureaucratic or professionalised meanings of förvaltning or skötsel. When that connection is established, when we can know the importance of nature, the need to ta hand om it. It is what you do for a heartbroken friend or a neglected houseplant, and it is what we ought to do with the environment more broadly. The metaphor of the hand even provides a helpful way of thinking of the different steps involved: in the friendly greeting and familiarisation, the hearty embrace and commitment, the concrete action and manual labour—and perhaps also, in symbol of the raised fist, a more transformative struggle to overhaul unsustainable societal and economic structures.

about the writer

Diana Wiesner

Diana Wiesner is a landscape architect, proprietor of the firm Architecture and Landscape, and director of the non-profit foundation Cerros de Bogotá.

Diana Wiesner

When I encountered the word “stewardship”, I instantly thought of the Colombian peasants, all those who save and protect seeds, food variety and biodiversity, without looking for anything in return.

In Spanish, the word stewardship has many translations: custodian, guardian, executor, administrator, caretaker, depository, protector, defender, keeper.

In this sense, the guardian of life is the one who takes care of something as if he had in his hands his own heart or his soul, he is the one who has the meaning of his own life, of his identity, of his culture.

When I was invited to take part in this reflection, I instantly thought of the Colombian peasants, all those who save and protect seeds, food variety and biodiversity, without looking for anything in return. They do it by conviction, as part of their own life, they have it rooted in their routine and in their sense of being.

So they say, “The seeds have no owner”, and question their marketing. Seeds are world heritage. In geographically isolated areas of Colombia, with social conflict trajectories, the tradition of saving seeds is part of existence. They call themselves “guardians of seeds”. In the tropical dry forest there are more than seventy peasant families for whom seeds represent powerful notions of solidarity economy, territorial rooting, renewal, identity, and cultural heritage. As Cristina Consuegra, an anthropologist and defender of agrifood heritage, points out, “this relationship of belonging, identity, and cultural memory symbolizes the very thread of people’s lives”, connecting them with the memories of their parents and grandparents. It is part of their family.

“My seeds, I adore them so much, I always look for the best place for them, for me, they are part of the family and they are my food”. — A woman from the village of Los Robles, Colombia.

Since 2002, in the department of Nariño, the Network of Life Seed Guardians began to be woven from the work of recovering seeds and crops in risk of extinction. The fundamental work of this network is focused on the conservation of native and creole seeds that are in danger of disappearing, through the rescue, preservation, promotion of sustainable use and consumption, and the transformation of food.

Besides the peasants, there are the so-called “neo-rural” groups, urban inhabitants who have migrated to the countryside with the conviction of having another consistent perspective with their principles of productivity, sustainability and family life. An example of this is a family that lives in the rural area of Bogotá, on the other side of the eastern hills of the city, who call themselves “family of the land, fruits of utopia” and seek to defend food diversity. They are the custodians of ancestral food and have rescued more than forty-five varieties of potatoes in spiral agroecology, traditional cultivation methods and prepare them with ancestral recipes, in one of the largest capitals of Latin America and humanity in general.

In the words of Jaime Aguirre: “we seek to rescue the biodiversity of the Andean edible seeds and to exchange with other agro-ecological brother processes; we aim to take care of seeds with love, dry them and cultivate them spiritually so that small farmers can continue «procreating» the land”; so that they can continue to be the guardians of life.

These are definitions obtained from the Network of Life Seed Guardians:

Guardián de semillas (Seed Guardian): the seed producer, who recovers, produces, conserves, investigates, selects and improves seeds in an agro-ecological context, shares them in a supportive and responsible way, and helps to dynamize their flow.

Semillistas (seedbed-ers): they are the future seed guardians, who are in the process of transition from conventional to agro-ecological agriculture. In the same way, they recover, produce and conserve seeds, without properly dynamize their flow.

Amigos de las semillas (Seed Friends): are people who help the network, making monetary donations or contributing with their work, from their profession, interest and energy, to the process of conservation and flow of seeds, without being producers themselves.

The custodians of life are all those who, through passion, conviction, a sense of identity and cultural memory, look after, guard and protect all expressions of life. The productivity of a country should be measured by its number of life custodians, which multiplies and promotes a deep transformation and rooting of the life identity in the regions.

References:

Consuegra, Cristina. “The thread of life: seeds and agri-food heritage”. University of the Andes. Department of Anthropology. Bulletin OPCA 10, Observatory of Cultural and Archaeological Heritage. April 2016. ISSN 2256-3139.

Gutiérrez, L. Seeds, common goods and food sovereignty. ” The Free Seed Network of Colombia” Available here.

Network of guardians of seeds of life Colombia “Sowing for the future”. July 1, 2016. Available here.

«Tengo el corazón de mi paisaje en mis manos, soy su guardiana. Si lo suelto, se desintegra». Gabriela Villate, 9 años. Foto: Diana Wiesner.

Isabel, “custodio” de semillas, ruralidad de Bogotá. Foto: Stefan Ortiz.

“Guardador” de semillas. Foto: El Salado Foto Andrés Estefan. Cortesía de Cristina Consuegra

Papas nativas, Usme. Foto: Stefan Ortiz. Cortesía de Cristina Consuegra

Custodios de la Vida

Cuando me encontré con la palabra “stewardship” en inglés, pensé instantáneamente en los campesinos colombianos, todos aquellos que guardan y protegen las semillas, la variedad de alimentos y la biodiversidad, sin buscar nada a cambio.

Cuando me invitaron a participar en esta reflexión, inmediatamente pensé en los campesinos de Colombia, en todos aquellos que guardan y protegen las semillas, la diversidad alimentaria y la biodiversidad, sin buscar nada a cambio. Ellos lo hacen por convicción, como parte de su propia vida, lo tienen enraizado en su rutina y en su sentido del ser. En cada región de Colombia a los guardianes se les llama de formas diversas: en Bogotá y su región se habla de custodios; en la costa son guardadores y en otras regiones cuidadores.

«Mis semillas, yo las adoro tanto, les busco siempre el mejor lugar, para mí, hacen parte de la familia y son mi alimento». Mujer de del Municipio de la Paz en la vereda los Robles. Cesar, Colombia.

Desde el año 2002, en el departamento de Nariño, se empezó a tejer la Red de Guardianes de Semillas de Vida a partir del trabajo de recuperación de semillas y cultivos en riesgo de extinción. La labor fundamental de la red está enfocada en la conservación de semillas nativas y criollas que están en peligro de desaparecer, a través del rescate, preservación, promoción del uso sostenible y consumo, y de la transformación de los alimentos.

Además de los campesinos, están los grupos denominados «neorurales», habitantes urbanos que han migrado al campo con la convicción de tener otra perspectiva coherente con sus principios de productividad, sostenibilidad y vida familiar. Ejemplo de ello es una familia que vive en la zona rural de Bogotá, al otro lado de los cerros orientales de la ciudad, que se autodenominan «familia de la tierra, frutos de la utopía» y buscan la defensa de la diversidad alimentaria. Son los custodios de los alimentos ancestrales y han rescatado más de cuarenta y cinco variedades de papas en agroecología en forma de espiral, métodos de cultivo tradicionales y las preparan con recetas ancestrales, uno de los mayores capitales que tienen América Latina y la humanidad en general.

En las palabras de Jaime Aguirre, cabeza de familia de la tierra: «buscamos rescatar la biodiversidad de semillas alimentarias de los Andes e intercambiar con otros procesos agroecológicos hermanos; buscamos cuidar las semillas con amor, secarlas y cultivarlas espiritualmente para que los pequeños agricultores puedan seguir “procreando” la tierra».

Definiciones obtenidas de la Red de Guardianes de Semillas de Vida:

Guardián de semillas: es el productor de semillas, quien las recupera, produce, conserva, investiga, selecciona y mejora en un contexto agroecológico, las comparte de manera solidaria y responsable, y ayuda a dinamizar su flujo.

Semillistas: son los futuros guardianes de semillas, que se encuentran en proceso de transición de la agricultura convencional a la agroecológica. De igual forma, recuperan, producen y conservan las semillas, sin dinamizar propiamente su flujo.

Amigos de las semillas: son personas que ayudan a la red, haciendo donaciones en dinero o aportando con su trabajo, desde su profesión, interés y energía, al proceso de conservación y flujo de las semillas, sin ser propiamente productores de las mismas.

Los custodios de la vida son todos aquellos que desde la pasión, la convicción, el sentimiento de identidad y la memoria cultural cuidan, guardan y protegen todas las expresiones de vida. La productividad de un país debería medirse por su cantidad de custodios de vida, lo que multiplica y promueve una transformación profunda y el enraizamiento de la identidad de vida en las regiones.

Referencias:

Consuegra, Cristina. «El hilo de la vida: semillas y patrimonio agroalimentario». Universidad de los Andes. Departamento de Antropología. Boletín OPCA 10, Observatorio del Patrimonio Cultural y Arqueológico. Abril de 2016. ISSN 2256-3139.

Gutiérrez, L. Semillas, bienes comúnes y soberanía alimentaria. «La Red de Semillas Libres de Colombia». Disponible aqui.

Red de guardianes de semillas de vida Colombia. «Sembrando para el futuro». Julio 1.º de 2016. Disponible aqui.

about the writer

Ferus Niyomwungeri

Jean Ferus NIYOMUNGERI is a young Rwandan conservationist, born in Southern province, currently serving as a Community Conservation Officer under the Rwanda Wildlife Conservation Association (RWCA), the non-governmental organization he started with.

Jean Ferus Niyomwungeri

Working with local communities and getting them on the board has shown an impact. They live day to day with natural resources and, with education and understanding, they respect and become more responsible, embracing the benefits of conservation.

Rwanda has built different institutions mandated to manage different aspects of environmental protection, climate change mitigation and adaptation and disaster risk management.

Rwanda has also made efforts to engage people in environmental protection through different home-grown solutions, for instance whereby all communities across the entire country gather on the last Saturday of the month for community work “Umuganda”, such as cleaning, repairing roads or planting trees. This has contributed a lot towards Kigali being one of the greenest and cleanest cities in Africa. However, Rwanda is one of the low-income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa / East Africa. It is highly populated and more than 70% of people are engaged in agriculture as small-scale farmers. This has led to the loss of forests especially in urban areas as Rwanda’s natural resources and land are overstretched. Many of our natural forests are threatened by their transformation into settlement areas and agricultural land as well as demand for firewood as the main source of energy, and the use of trees for construction despite the government’s efforts towards conservation.

In this context, RWCA has contributed a lot to protect wildlife and natural habitats, engage and educate local communities while improving livelihoods and raise awareness of conservation issues. Our project of saving the endangered Grey Crowned Cranes where we work with people who kept cranes as pets in their home or hotel. With time, people have understood the issues contributing to the cranes’ decline in numbers and have changed their mind about keeping cranes in captivity and decided to contribute to the process of saving them. This project has showed how, with education and awareness raising, our communities were collaborative and supportive of the plan to reintroduce the cranes to the wild.

RWCA’s conservation model includes creating a sense of ownership and stewardship of cranes in order to create long term sustainable solutions to the project. Without this, the illegal trade would likely continue. For example, we have a team of 25 marsh rangers, recruited from the community around Rugezi marsh, a RAMSAR protected site rich in biodiversity and home to nearly a quarter of Rwanda’s Grey Crowned Cranes. Their role is to patrol and protect the marsh but a large part of that is educating people about the need to protect it and creating a sense of ownership over our country’s wildlife.

We also have a team of 30 Conservation Champions across the country located at key biodiversity areas and crane habitats. They are also recruited from within the communities they serve – they monitor cranes and other biodiversity in those areas and again educate people about the role of local communities in environmental protection. Our activities also include planting indigenous trees to restore habitats for the benefit of biodiversity. This activity also takes on the idea of stewardship, where we encourage communities to focus on “growing trees” not just “planting trees”, following up and caring for their trees in the long term. Working with local communities and getting them on the board has shown an impact since we started. They are the ones who live day to day with those natural resources and, with education and understanding, they respect and become more responsible, and embrace the benefits of conservation.

about the writer

Huda Shaka

Huda’s experience and training combine urban planning, sustainable development and public health. She is a chartered town planner (MRTPI) and a chartered environmentalist (CEnv) with over 15 years’ experience focused on visionary master plans and city plans across the Arabian Gulf. She is passionate about influencing Arab cities towards sustainable development.

Huda Shaka

“With God’s will, we shall continue to work to protect our environment and our wildlife, as did our forefathers before us. It is a duty, and, if we fail, our children, rightly, will reproach us for squandering an essential part of their inheritance, and of our heritage” —Source

The above quote from the founder and first president of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, encapsulates the culture of environmental stewardship in the country. It is a view rooted in the Islamic concept of vicegerency: the responsibility bestowed by God on human beings, which entails them being trustees of the earth. More recent concepts of sustainable development and intergenerational equity are also echoed in Sheikh Zayed’s quote above.

Environmental stewardship in the UAE is rooted in the Islamic concept of vicegerency: the responsibility bestowed by God on human beings, which entails them being trustees of the earth.

Sheikh Zayed’s environmental vision also included utilizing the best expertise and technological innovations to literally “green the desert”. This involved ambitious agricultural, tree planting, and forestry projects to help provide employment, food security, and aesthetically pleasing and comfortable cities and towns for the new country’s residents. The forests functioned as green belts, protecting farms and human settlements in the desert from sand storms. Of course, they came at a water cost with ground water being the only feasible water source.

Over the last decade, the discourse around environmental stewardship has evolved to encompass broader environmental aspects, particularly from a resources’ perspective. In 2006, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) declared the UAE as the country with the largest ecological footprint per capita, surpassing even the United States. This served as a wake-up call for the country’s residents and policy makers.

Since then, environmental stewardship at a policy and grassroots level has developed to encompass water and energy conservation and carbon reduction, as well as ecological conservation. The UAE now has a national energy strategy which includes renewable energy and carbon reduction targets. Similarly, a national water security strategy has been developed to ensure sustainable access to water. These targets are also reflected in local strategies and increasingly in building codes and rating systems. Ambitious development projects such as the Masdar City project aim to pioneer environmentally-sustainable technologies for survival in the desert, and in other resource-constrained contexts.

Today as the UAE is about to celebrate its 48th national day, environmental stewardship remains a concept which carries meanings of visionary leadership rooted in a deep cultural appreciation and understanding of the environment’s value and the present generations’ responsibility towards preserving it for future generations.

about the writer

Abdallah Tawfic

Abdallah is an architect, environmentalist and urban farmer. He works at the German International Cooperation (GIZ) and he is also the cofounder of Urban Greens Egypt, a startup aiming to promote the concept of Urban Agriculture in Cairo.

Abdallah Tawfic

We strive to understand the benefits of urban greenery and eventually have the chance to use it for good—that’s how we define stewardship in Cairo without acknowledging it as an understandable term on its own.

Looking at the history of this informal construction, those were productive agriculture land in the early 60s, that has transformed incrementally through time—with the absence of laws—into unplanned urban dwellings. The informal construction approach is usually simple:—“build on 100 % of the plot”—so imagine the 60 years aftermath of this continuous fertile land encroachments.

“The students do not understand why and where should we plant more trees and greens” said Omayya, a “Mattariya School for Girls” teacher whom we trained on rooftop gardens implementation & management. “Our urban pattern is challenging, the students living in the neighborhood are completely disconnected from nature”, she added.

The teachers have created rooftop gardening teams of interested students, where they get the chance to be reconnected to nature and learn more about how to produce their food within the boundaries of their neighborhood. They have learned new mechanisms of reviving the original function of this land in an innovative, environmentally responsible and contemporary way. They understand that this land has evolved long time ago to be agriculturally productive, and the aftermath of unprecedented urbanization should not stop them for seeking their rights to enjoy being around green spaces and learn how to locally grow their own food.

We want to change this persistent culture of environmental injustice that has accumulated over years. We want to create stewards taking the lead for a better and greener future.

The students deserve to understand the benefits of urban greenery and eventually have the chance to use it for their own benefits, that’s how we define stewardship in our city without acknowledging it as an understandable term on its own. Stewardship—Idaara in Arabic—is a classical translation for “supervision and management”. Teachers of Mattariya school for girls are stewards—or Environmental Managers if we wish to formulate it in English—who are passing the culture of rooftop community gardens to the new generations. They will one day not only apply it on their everyday activities, but create innovative approaches that improves the quality of life in such challenging living environment.

about the writer

Heather McMillen

Heather McMillen is the Urban & Community Forester with the Hawaiʻi Department of Land & Natural Resources.

about the writer

Kirk Deitschman

Kirk loves all aspects of Hawai’i. Throughout his life he has always been involved in uplifting and supporting communities of Hawai’i. His other passion is to continue to learn about the natural resources of Hawai’i and join the efforts to support and protect these important resources.

Heather McMillen and Kirk Deitschman

Aloha ʻĀina, stewardship in Hawaiʻi

What is aloha ʻāina? Alo (face) and hā (breath) = aloha, to exchange breath with another being, the essence of reciprocity. Aloha is also love, affection, compassion. ʻĀina encompasses everything living.

Our understanding of stewardship is grounded in the Hawaiian concept of ʻāina. ‘Āina is land, sea, and all biotic/abiotic elements and processes. It is also sometimes translated as “that which feeds” because it nurtures the spirit and the body. People are in reciprocal relationships with ʻāina as part of an integrated system. In Hawaiian there is no word for “nature” as an entity that is separate from people. The proverb “I ola ʻoe, i ola mākou nei” underscores our interdependence. It means: your life depends on mine, and my life depends on yours. When you thrive, we thrive. We see that these concepts are foundational to aloha ʻāina, an ancient concept that we understand as stewardship.

What is aloha ʻāina? Alo (face) and hā (breath) = aloha, to exchange breath with another being, the essence of reciprocity. Aloha is also love, affection, compassion. ʻĀina, as described above, encompasses everything living. Through Hālau ʻŌhiʻa, we (the authors) have deepened our understanding of aloha ʻāina and our kinship to ʻāina. We recognize genealogical ties to ʻāina (i.e., I am connected to this mountain as much as I am to my maternal grandmother), and we care for the ʻāina as we would a dear family member (i.e., by protecting her). This is true for those of us born here and not, because we all drink the water and breathe the air of Hawaiʻi. The proverb: “I nā mālama ‘oe i ka ‘āina, na ka ‘āina malama iā ‘oe,” tells us if you take care of the ‘āina, she will take care of you. The opposite is also true, if we neglect the ʻāina, we will be neglected. The practice and process of aloha ʻāina requires pilina (relationship), in this case, relationships among people and place.

Aloha ʻāina is embodied in the protection of Maunakea (also Mauna Kea or Mauna a Wākea, “mountain of Wākea”, sky deity and ancestor of all Hawaiians). Since July 2019, kiaʻi (protectors or guardians) have occupied the sacred mountain in efforts to prevent further development for telescopes, specifically a telescope that would be 18 stories tall and 30 meters in diameter on an 8-acre footprint in a fragile, rare, subalpine ecosystem. This movement is based in aloha ʻāina and kapu aloha (multidimensional practice of compassion and peaceful consciousness for all especially for those perceived to have oppositional intentions). In the last three months as we have all held space—physically by being on the Mauna and also spiritually as we stay connected to the Mauna at home—we have all felt the cultural and cognitive shift being ignited across Hawaiʻi and around the globe. The momentum has energized and informed other communities to protect places from development and desecration, to promote opportunities to nurture pilina with ʻāina and with each other. The movement to protect Maunakea has become a reference point for aloha ʻāina and healing in Hawaiʻi and worldwide.

about the writer

Ragene Palma

Ragene Palma is a Filipino urbanist currently studying International Planning at the University of Westminster, London, as a Chevening scholar. Follow her work at littlemissurbanite.com.

Ragene Andrea L. Palma

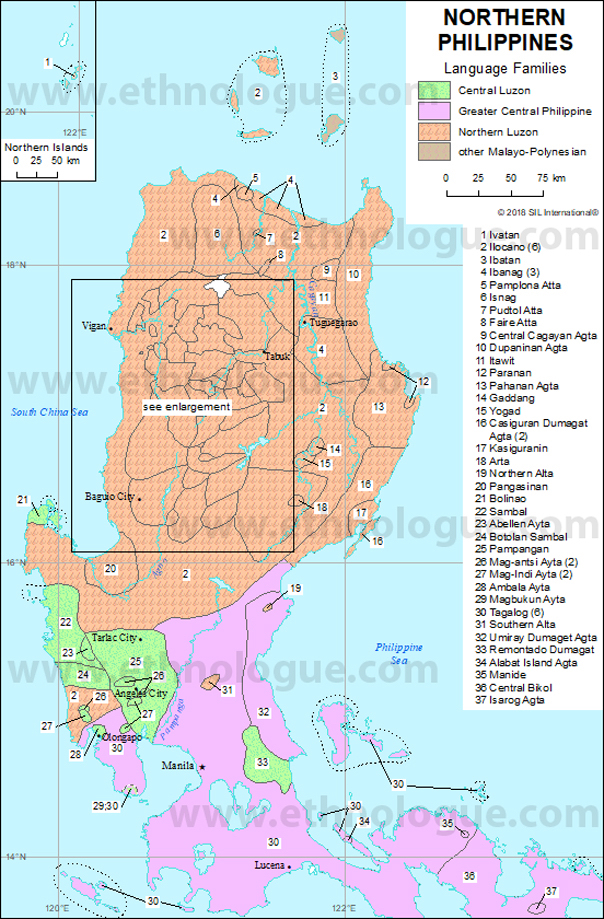

The words across the many languages of the Philippine to understand “steward” and “stewardship” are reflective of the peoples’ inherent nature to care for someone or something, to stand for duty, to protect, and to help or to respond to a certain need.

The scope of “Filipino”

Understanding Filipino (the national language) entails understanding the origin of the places where the many languages are spoken, how Filipinos have moved and lived across islands throughout history. Ethnologue provides detailed maps of the Philippine language families.

Translations across the three major island groups of the Philippines would show similarities of meaning in understanding stewardship. Below are select translations from the different languages.

Luzon islands

In Tagalog, what comes to mind when translating “steward” is tagapangalaga (someone who provides care). A rapid survey would also draw responses such as bantay (someone who looks out for someone), katiwala (a person with whom one entrusts important things), tagapangasiwa (one who facilitates or manages), and gabay (guide). In Kapampangan, “steward” is manyese (someone who takes care of another), or maningat, which roots from ingat, meaning “care”. In Ilocano, “steward” is taga-aywan (someone who provides care).

Visayas and the Bicol region

In Cebuano (or Bisaya), Hiligaynon, and Ilonggo, “steward” is tinugyanan, tigbantay, and taga-atiman (carer); in Bicolano, it is translated to taga-ataman (ataman being word that means protecting, nurturing, and providing care).

Mindanao

In Meranaw, “steward” comes close to kithatandingan, meaning someone who is in charge of a responsibility; thatandingan would refer to the act of protecting one’s own jurisdiction as a form of duty. In Tausug, “stewardship” comes close to daraakun, which is the act of taking care of, and serving others. A common word of the Moro tribe (the Islamic groups of Mindanao) is pamarinta, meaning the authority and responsibility over a certain area. This understanding is very much rooted in how the Moros associate with their home and their environment; in fact, Meranaw means people of the lake (ranaw being lake).

In Binukid, there are related words to stewardship: tulubagën (literally, “to respond”) means a general sense of responsibility; pëgpangamangël leans towards a more directed sense of responsibility for the community and the ancestral domain, and katëngdanan (which stems from the root word katënged, meaning duty).

In the Spanish-Filipino creole Chavacano, cuida means “to act as a steward for”.

Stewardship reflects care, duty

The Filipino words to understand “steward” and “stewardship” are reflective of the peoples’ inherent nature to care for someone or something, to stand for duty (a trait that comes with strong familial responsibility), to protect, and to help or to respond to a certain need.

Filipinos have strong ties to land and the natural environment as a home. It is beautiful how our indigenous groups, who have lived way before the colonial period and the establishment of the government, refer to our lands as lupang ninuno (ancestral lands); this gives context as to why our languages show respect, a certain fierceness (for duty), and affection (giving care), in understanding “stewardship”

Thank you to the following for contributing the translations and context for the Filipino languages: Salic ‘Exan’ Sharief, Jr. (for the Moro tribe languages), Rachelle Santos (Kapampangan), Yowee Gonzales (Cebuano, Hiligaynon, and Ilonggo), Ceng Bilgera and Keesha Buted (Ilocano), Jessie Lapinid (Chavacano), PJ Capistrano (Binukid), and Peter Fraginal (Bicolano).

Note: Simons, G. F. and C. D. Fennig (eds.). 2018 Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 22nd ed. Dallas: SIL International. www.ethnologue.com/country/PH/languages (Accessed 4 October 2019)

about the writer

Patrick M. Lydon

An American ecological writer and artist based in East Asia, Patrick uses story and community-based actions to help us rediscover our roles as ecological beings. He writes a weekly column called The Possible City, and is an arts editor here at The Nature of Cities.

Patrick Lydon

The human is steward of nature, yet only just as nature is steward of humans. Rather than hierarchy, there is mutuality built into this relationship.

We were curious. Though this man was leader of the local fishermans’ association, and a lifelong fisher, he was somehow just as interested in the mountain as he was in the sea.

We asked if there was something lost in translation from Japanese to English.

The fisherman shook his head and reiterated: “I don’t fish from the sea”.

Sitting on the traditional tatami floor of the Fisherman’s Association building, all we could do was stare at him in confusion. He continued “You can’t fish by looking at the sea. Yeah? You’ve got to fish by looking at the mountains first. The lives of the fish in this sea start with the rains that fall on the mountains. That rain works through the forests, through the agricultural fields, through the town, and then, it becomes the sea. If the mountain is not a healthy environment for the things that live there, the same is true for the sea.”

I ask, timidly “So, you fish from your boat, in the sea, but you are looking at the mountain?”

The fisherman looks at me, not so much annoyed, but quizzically, as if to say, is there any other way?

This man fishes from the mountain because he—and presumably most of the traditional village fishermen like him—understand that in some way everything in this ecosystem depends on the health of every other part.

It’s a recurring theme with the farmers, fisherman, monks, chefs, and traditional craftspeople we have met over the past several years in this part of the world; the human is steward of nature, yet only just as nature is steward of humans.

Rather than hierarchy, there is mutuality built into this idea of stewardship. It is a relationship.

From this viewpoint, humans are no more or less important than any other living being on this earth, and all actors in this ecosystem must play their part, taking their action with “truth, goodness, and beauty” as both fishermen and nearby natural farmers say.

This is not an isolated thought by old farmers and fisherman. Indeed, when the entire village here comes together to celebrate the sea, it starts the festivities from the mountain, moving through the town, and into the sea.

It took this particular fisherman 70 years living on this island, and generations of wisdom passed down to him, to know what it means to fish from the mountain. That the office worker in Tokyo knows almost nothing of this anymore is a critical problem for cities.

Here on the island called Megijima, when we witness the last generation of people who want a job that requires them to know their role within the ecosystem, we are witnessing the extinction of knowledge. The lessons we might learn, not only from Japanese fishermen, but from similar keepers of traditional knowledge around the world, are about to be lost forever.

We who dwell in the cities, believe that such knowledge has no relevance to our staunch urban fortresses. Yet, truth is, the walls of our cities will most certainly crumble with the loss of this knowledge.

The lessons we need in order to build something akin to a sustainable society will not come from technology. They will not come from reports, graphs, or data analysis of the people who live this way. They will not come from financial growth, profits, investments, or dividends. The lessons we need will only come from our willingness as individual human beings to go, see, experience, and learn from those who know how to live withthe land, and how to become partners again, with the rest of the natural world with which we dwell.

Only if we can do this, will we know what it means to be stewards, and to develop technology, monetary systems, and all else in appropriate ways.

Saving these ways of thinking, living, and being are not just odes to a time long gone, they are the roots that will ensure our continued survival as a species here, no matter if we live in mega city or fishing village.

about the writer

Artur Jerzy Filip

Architect, researcher, and practitioner in the field of urban planning and design and author of the book “Big Plans in the Hands of Citizens”. He is the curator of the educational :WCENTRUM project. Assistant Professor at the Warsaw University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture.

Artur Jerzy Filip

In Poland, our phrase has been “lokalni gospodarze”, which translated back to English might be something like “Local Hosts”. It has enabled us to escape old schemes of thinking about civic participation and cross-sectoral governance.

Two years ago I co-curated an exhibition “Warsaw Under Construction” at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. My part was dedicated entirely to the idea of stewardship. On that occasion we faced the linguistic challenge for the first time and ended up with the translation “Lokalni gospodarze”. “Lokalni” meaning devoted to environments, though not necessarily natural or green, actually any kind of urban spaces included. And “gospodarze” meaning the hosts, the ones who manage and keep space in good condition. Actually, if someone would try to translate the phrase “lokalni gospodarze” back from Polish to English, we might get something like “Local Hosts.” Fair enough as well. What is key, after all, is this combination of two fundamental elements. First, public environment considered within particular boundaries: the turf. And second, the ones who care for the turf. All the rest: their modes of operation, levels of cooperation, and ways of calling things might vary across the cases.

In Poland, the conceptual framework of urban—environmental, local, you name it…—stewardship has already proven its usefulness. In some cases, it has served as a handy term to describe and evaluate ongoing projects. In others, as a mind-opening perspective allowing for broadening the visions. On multiple occasions I conducted workshops and gave lectures for citizens, institutions, authorities, and business leaders to share this idea. Today I’m so happy to see that the term “lokalni gospodarze” has already been starting to be commonly used here as a way enabling to escape old schemes of thinking about civic participation and cross-sectoral governance, as we have used to call these things so far. The alteration is significant. The openness and flexibility of the term “lokalni gospodarze” enables us to work on collaboration without being constrained by any rigid formulas established in advance, especially since we still do not have many ready-to-use formulas (policies, programs) that would facilitate multiple and diverse stakeholders to collaborate in support of urban space preservation, maintenance, or development.

about the writer

Beatriz Ruizpalacios

Beatriz Ruizpalacios is a PhD student in Sustainability Science in Mexico City. She has worked with different communities in urban and rural settings facilitating sustainable development processes.

Beatriz Ruizpalacios

Stewardship means nurturing a thing or a place and the relationship we keep with it. We become responsible, and in turn the thing is a repository of our affection and care. There is no particular word for this kind of stewardship, but we prefer to use verbs that emphasize our responsibility and agency: Cuidar, Proteger.

Many governmental and private programs promote stewardship as being guardians of the environment. Stewards in protected natural areas are hired as park rangers encouraged to enforce regulations and communicate biodiversity and environmental services highlights to visitors. In many protected areas park rangers are residents whose traditional livelihoods depended on the use of natural resources. As the area was declared a protected area and regulations were implemented to control biodiversity use and change in land cover, the residents were considered problematic in formal conservation efforts, so they were offered jobs as park rangers, known in Mexico as “guarda parques”.

Another embodiment of stewardship is promoted by companies with outreach programs that involve their employees and neighbors in conservations efforts. Reforestation is a favorite because it gathers families, friends, and co-workers in collective outdoor activities that last a full day and offer the opportunity to reconnect with nature and strengthen community ties. Participants are encouraged to become defenders or guardians of trees and forests and hence of nature, while reclaiming public spaces and a sense of community and belonging. At the end of the day, these “guardianes de la naturaleza” go back home knowing they are part of a bigger movement that aims at building a better world for all species to thrive.

When we talk about the personal sphere, however, as civilians with personal initiatives in our community or family members in a household, stewardship entails a personal relationship with specific things. It becomes a one-to-one relationship with things that we are interested in, that we like, that we are fond of, that carry part of our history, and which we wish to preserve. In these intimate environments, stewardship means nurturing a plant or a place and the relationship we keep with it. We become responsible for its continuity and wellbeing and in turn the thing is a repository of our affection and care. It becomes part of our daily routine and something worth our energy and money. There is no particular word for this kind of stewardship, but we prefer to use verbs to describe the relationship emphasizing our agency and the subject in diminutive form, which expresses our affection towards it: “Yo cuido a mis plantitas”, which in English would be translated as “I take care of my little plants.” It is a personal relationship of ownership and responsibility of something tangible based on interests, personal experience and memory, and that derives into a relationship of obligation towards its welfare.