Introduction

about the writer

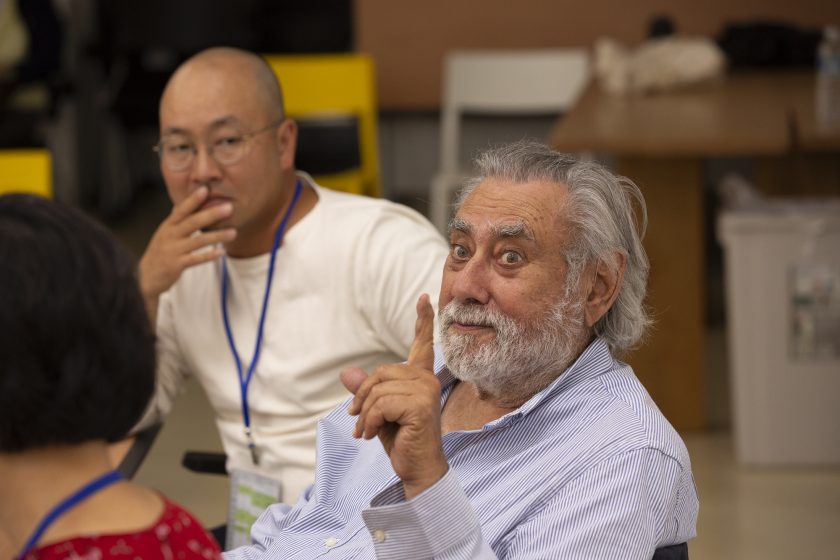

Chris Fremantle

Chris Fremantle is a producer and research associate with On The Edge Research, Gray’s School of Art, The Robert Gordon University. He produces ecoartscotland, a platform for research and practice focused on art and ecology for artists, curators, critics, commissioners as well as scientists and policy makers.

about the writer

Anne Douglas

Anne Douglas is a Professor Emeritus, previously Chair in Art in Public Life at the Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen Scotland. She has focused, over the past 25 years, on developing doctoral/postdoctoral research into the changing nature of art in public life, increasingly in relation to environmental change.

In Berlin, the Harrisons characteristically turned their attention to a possibility of healing brought about through ecological understanding, creating a proposal that enfolds the destruction of the infrastructure of terror, reducing it to rubble and then lending itself to new life through the forces of nature.

The Harrisons (Helen Mayer Harrison (1927-2018) and Newton Harrison (1932-2022) are widely acknowledged as pioneers in bringing together art and ecology into a new form of practice. They worked for over fifty years with biologists, ecologists, architects, urban planners, and other artists to initiate collaborative dialogues. The works they made in various places from the second half of the 1970s stand as proposals for putting the well-being of the web of life first. The Harrisons’ visionary projects have, on occasion, led to changes in governmental policy and have expanded dialogue around previously unexplored issues leading to practical implementations variously in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

In writing and inviting people to contribute we sought advice and received extensive help from both the Harrison Studio/Center for the Study of the Force Majeure (CFM); from Kai Resche and Petra Kruse, curators and editors with the Harrisons (and also the Berlin branch of CFM), as well as from David Haley (who was the project manager for Casting a Green Net and Associate artist for Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom (2007-09).

We offer the following passage from one of the Harrisons perhaps less well-known works as a prompt, encapsulating their approach:

Trümmerflora, or rubble plants and trees, are a special phenomena unique to heavily bombed urban areas. The bomb acts as a plough, breaking brick, mortar, metal, and wood into fragments and, in a single gesture, mixing these with earth from below. The earth often contains seeds, dormant from the time of first construction on the site, that may have been buried for a century or more. These seeds come to light, and those that can live in this new and special earth, grow and flourish. Other seeds, dropped by wind and by animals, also survive in limited numbers in this new soil, this rubble. Hence the name Trümmerflora, or loosely translated, rubble flowers.

Harrison and Harrison 1990 ‘Trümmerflora: on the Topography of Terrors’ in Polemical Landscapes California Museum of Photography pp 12-13

This 1988 work by Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison during a period of residency in Berlin emerged in response to overlooking the derelict site that had been the headquarter of the Gestapo, Storm Trooper, and Secret Service Operations, i.e. the bureaucratic center for the Death Camps and Labour Camps of the Nazi regime. Earlier attempts by others to create an appropriate monument or memorial to the horrors of this urban site had failed. As Jewish people, this site was hugely significant. However, the Harrisons characteristically turned their attention to a possibility of healing brought about through an ecological understanding of the site, creating a proposal that enfolds this history, the destruction of the infrastructure of terror reducing it to rubble, lending itself to new life through the forces of nature.

Read an extended version of this Introduction.

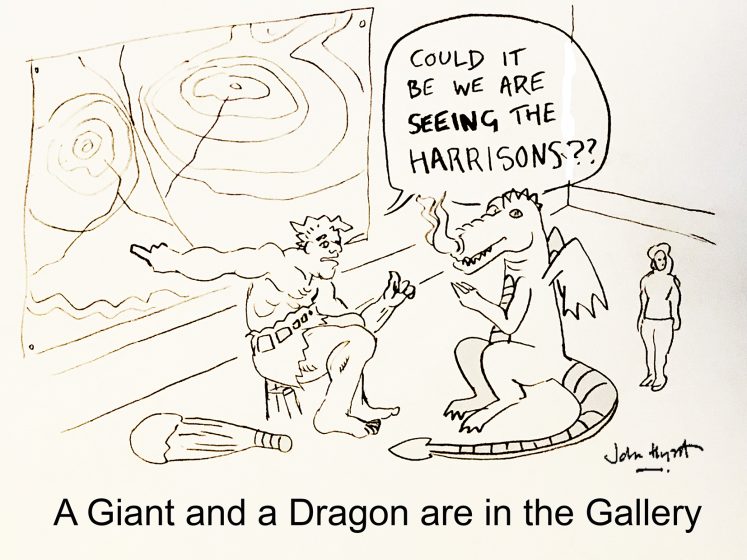

The contributors to this round table, including artists, curators, environmentalists, landscape architects, and scientists, have all reflected on what they learned from meeting and working with the Harrisons. For some, this starts with Portable Fish Farm: Survival Piece #III which caused a furore when it was exhibited at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1971. A number of others were involved in various ways (curator, environmentalist, scientist, artist, and project manager) with the Harrisons’ work Casting a Green Net: Can it be we are seeing a Dragon? (1998) made as part of ‘ArtTranspennine98’, a major regional collaboration between the Tate Gallery Liverpool and the Henry Moore Sculpture Trust. Others have much more recent experiences of Newton Harrison as he continued the practice, including curating an exhibition Eco-art Work: 11 Artists from 8 Countries for Various Small Fires in Los Angeles in 2022, and developing the work Sensorium.

Contributors reflect on how working with the Harrisons in various different ways informed, changed, and developed their practices. Some talk about having the strictures of their respective disciplines and working practices lifted and their thinking transformed. Others talk about the love, the love between the Harrisons, and the wider empathy reaching beyond human-centredness that they engendered.

Click here for a more in-depth reflection regarding this roundtable.

Richard Scott

about the writer

Richard Scott

Richard Scott is Director of the National Wildflower Centre at the Eden Project, and delivers creative conservation project work nationally. He is also Chair of the UK Urban Ecology Forum. Richard was chosen as one of 20 individuals for the San Miguel Rich List in 2018, highlighting those who pursue alternative forms of wealth.

Their practice was enabling and real and embodied timeless wisdom for people and nature, and these principles and their artworks will stay with me.

At the 1999 Society for Ecological Restoration (SER) Conference in San Francisco, a special art group was formed. David Haley from Manchester Metropolitan University proposed and went on to curate The Harrison Studio to contribute to the 2000 SER Conference in Liverpool. The work they presented and spoke about, Casting a Green Net: Can it Be We are Seeing a Dragon? was the first artwork I had seen that visualised and projected landscape-scale restoration within the context of climate change, poetically describing the need for us to “gracefully withdraw”.

The Harrison’s work was so playful and was the first time I’d seen artists enhance and translate classic ecological methodologies, signaling how we need to be bold. The Dragon highlighted the green East-West corridor between the river estuaries of the Humber and the Mersey. The Ordnance Survey maps hung splendidly on the wall of the Adelphi Hotel in Liverpool and made for a very memorable piece because the shape of the biodiversity across the North of England equated to that of a dragon, sparking imagination. Significantly it almost exactly mirrored the original outlines of the proposed new Northern Forest (2018), and it definitely influenced the ambition of our thinking about the Northern Flowerhouse.

As the organisation Landlife was closing, our vision for wildflowers as infrastructure and the locally coined ‘Northern Flowerhouse’ took shape, and the Singh Twins designed it up for us. Their art is doubly powerful, as they strengthen each other’s resolve and knowledge base, in the way they depict historic and current exploitation and the way in which they share traditional cultural practices and meanings. Working with my partner, Polly Moseley, enabled me to access and understand more of the calibre and potential of artists on Merseyside and to understand how important the Harrison’s partnership was over time.

In a video conversation, Newton said, “Overburden yourself, reflect and compose and look for original avenues” He talked of “playing catchup”, and spoke of big backyards and massive change ― accommodating the air, the land, the soil, and area ― above all avoiding ‘tower’ thinking of academia, and connecting with and through the citizen. Their work always included messaging, which was accessible and layered, like the messaging through Peter Carney’s banners, which have become our wildflower totems at events. Landlife (1975 – 2017)’s tenet which we attempted to embody was “creative conservation”.

Their Force Majeure “framed ecologically” was about articulating an evolving and boldness of vision ―this theme keeps appearing― and bold vision, and it reminded me of the simple advice from great gardener and writer, Christopher Lloyd, when he witnessed our wildflowers project in Liverpool in 1999, “Be bold” he said. The Harrisons always were direct and unapologetic with their work, including the Endangered Meadows of Europe. They understood the power and symbolism of moving meadow to cover an acre and a half rooftop on the top of the largest and most visited museum in Bonn, Germany, including an opening speech delivered by Angela Merkel. In Liverpool, we have positioned our landmark and gateway sites, around the Everton Lock Up badge, or along much-used trunk roads, and the Mersey Tunnel to achieve visibility, paving the way for a mosaic of habitat, urban or rural. It is about what we can do in different places, together, with real communities of interest, and heart and soul principles, be it Merseyside, Manchester, Cornwall, Morecambe, Dundee, or Auchterarder. And with the irony and humour reflected in Jamie Reid’s “Nature Still Draws a Crowd” (Suburban Press 1977). We worked with Jamie to create a large Ova in a huge field of wildflowers at the Lost Gardens of Heligan last summer. I think the Harrison’s would have approved.

The Harrisons to me were intriguing, curiosity-raising, and pragmatic. The more you found out about their work, the more depth it offers. Some were shocked by it. Spike Milligan ― a patron of Landlife the charity I worked for for 26 years ― was one. Spike arrived outside the 11 Los Angeles Artists exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1971 and smashed the Haywards’ glass front doors with a brick! The Harrisons were exhibiting a Portable Fish Farm an ecosystem that could be harvested and eaten. This triggered headlines, Arts Council anxiety, and questions in Parliament. When I discovered this, “Blimey” I thought.

The Harrisons’ philosophy avoids despair and wasting energy. For example, noting Scotland has a million foragers, and every person could have one hectare of land, points towards land reform with poetry and chutzpah. For me, the currency of seed and what you can do with it, experimenting with soil and substrates, and signaling massive change are all vitally important. As ecologists, we should take heart in reflecting on the work of the Harrison Studio, their belief in the power of the spoken word and bardic mystery, and their intolerance of technocracies. With wonderful dialogue of the possible, they brought attention to detail and employed simplicity. For example, in the recreation of Hog Pasture: Survival Piece #I Wilma the Pig in 2012, how the Harrisons restaged that with joy, again, featuring meadow pasture and a pig (the pig had been denied by the art gallery the first time round).

Last year in 2022, I launched the Cultural Soil Charter (which grew out of discussion with the Chartered Institute of Ecology and soil advocates across the UK) at the World Congress of Soil Science in Glasgow, and was thrilled this coincided with the British Soil societies staging of Newton Harrison’s On The Deep Wealth Of this Nation, Scotland. I checked back and reflected on Making Earth (1969-70) when Newton made topsoil in front of his studio, and this connected in my mind with Glasgow CCA’s 2022 exhibition of tonnages of live soils. The Eden Project would do this as the origin of their own journey in building a theatre of plants and invite others to observe and participate, to show what we want to do with circular economies for soil, urban substrates, and what we can grow on them.

The Harrisons read this piece on ‘Mixing Mapping and Territory’ (2013):

Where would you begin? Where the terrain permits and the will exists. Choose Your Mountain. That is to say you can begin anywhere.

Their practice was enabling and real and embodied timeless wisdom for people and nature, and these principles and their artworks will stay with me, as Scouse Flowerhouse develops as a co-operative, and the National Wildflower Centre’s creative conservation work grows, in many ways, we will continue to honour and riff off their work.

Cathy Fitzgerald

about the writer

Cathy Fitzgerald

Dr. Cathy Fitzgerald, Founder-Director of the global online HAUMEA ECOVERSITY. Empowering creative, cultural, and business professionals for wise, compassionate, and beautiful creativity. Consultant, international speaker, advisor, and mentor on ecoliteracy & accredited ESD transformative learning Earth Charter educator and Research Fellow on Art & Ecology for the Burren College of Art.

For me, this is the most profound legacy of the Harrisons’ work – understanding how creativity is an essential driver for holistic ecopedagogy across all education.

Helen and Newton Harrison’s work has powerfully influenced my thinking and creative practice since the late 90s. I still clearly remember the afternoon coming across a summary journal article about their work in the library of the National College of Art and Design in Dublin, Ireland. I recall feeling intense relief at finding a comprehensive articulation of the multi-constituent aspects of ecological art practice and over time it shone a light on a path for me to develop similar creative ecological endeavours. The Harrisons’ reflections on their dialogical, participatory, question-led practices helped me understand why integrated, more holistic practices are a radical departure from the conventions of modern art, and why they have the social power to inspire people to live well for place and planet. Today, largely inspired by the Harrisons’ practice over many decades, I would argue ecological insights must inform and guide creative practice—and all our activities—for personal, collective, planetary, and intergenerational well-being.

However, with little college or peer support, my progress to develop and articulate a similar practice to the Harrisons was very slow. Around the late 90s, I was also reading art critic Suzi Gablik’s Re-enchantment of Art and Conversations Before the End of Time. For many years afterwards, I was mystified why the Harrisons’ and Gablik’s work was rarely discussed in my undergraduate or postgraduate art studies, or even during doctoral research that I completed in 2018. Looking back, I believe I came to this topic earlier than most because I had previously worked in science and environmental advocacy. It also took me time to appreciate that illiteracy around ecological understanding, common in current art education, profoundly precludes many from understanding the gravity of humanity’s predicament, and correspondingly why ecological insights insist on a paradigm shift in contemporary art and the dominant culture as a whole.

My difficulties to develop an ecological art practice continued through my doctoral studies; I found it difficult to push past artistic conventions and disinterest that the ecological emergency was a crisis of the dominant culture. Even with my background in science, I had to persist to explain my audacity to explore creative practices that crossed disciplinary boundaries and lifeworld experience. Here the published journal articles on the validity and importance of the Harrisons’ pioneering prescient practice, with others following in similar ways, literally gave me permission to continue my practice and research. I will always be grateful, remembering a particularly difficult time around 2011 when I was considering abandoning my doctoral studies, when Helen and Newton wrote to me out of the blue ‘Dear Cathy, from our perspective, very good work!’

Today, I feel the relevance of the Harrisons’ work is stronger than ever. I can also confirm that the importance of their journey to develop and articulate ecological practice extends beyond the contemporary art world to contribute to envisioning best practices in broader sustainability education. These realisations arose recently after an unexpected opportunity to learn with leading international sustainability educators at Earth Charter International, which hosts the UNESCO Chair of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). Looking at their key research insights of emergent holistic education for sustainability —integrated approaches to advance wisdom on how we must live well with others and the wider Earth community— I realise that the Harrisons’ real-world ecological art practices, facilitating communities to creatively question and embrace many ways of knowing, exemplify developed participatory, multiconstituent ecopedagogy. Additionally, the Harrisons provide much insight to sustainability educators on how creative practices, in particular, are essential to make sustainability learning inclusive and inspiring to diverse communities. As our society and the art world becomes more ecoliterate, I believe the Harrisons’ (and similar creative-led ecological practices) leadership will be more appreciated. For me, this is the most profound legacy of the Harrisons’ work – understanding how creativity is an essential driver for holistic ecopedagogy across all education.

Terike Haapoja

about the writer

Terike Haapoja

Terike Haapoja is a visual artist based in New York. Haapoja’s work investigates the existential and political boundaries of our world, with a specific focus on issues arising from the anthropocentric world view of Western traditions. Animality, multispecies politics, cohabitation, time, loss, and repairing connections are recurring themes in Haapoja’s work.

For Newton, this kind of awakening had happened early in life, when he was driving along a highway in California, seeing the broken landscapes under constant, violent human excavation. Suddenly, he said, he could hear the earth screaming.

Like many, I was introduced to Helen and Newton Harrison’s work in art school. In the early 2000s, when I studied, ecology wasn’t yet trending, and their work seemed like fresh air for someone like me who felt that the most urgent question in the world, the environmental crises, was surrounded by a numbing silence. My own work, however, was video-based and centered on the figure of the animal, and while our works sometimes ended in the same shows, we never met in person.

Then, on one dark evening in 2019, I saw a message request on Facebook, and when I clicked on it I found a message from the legendary Newton Harrison. He had encountered one of my works somewhere and wished to connect. I was delighted and honoured, and we started an exchange that evolved into emails and Zoom calls and lasted until his passing.

One of the first works he sent me was a meditation on sea ecologies called Apologia Mediterraneo. The ten-minute video combines found footage and Newton’s voice-over, reciting a poetic letter addressing the sea and the troubles and pains it has to endure. Newton’s voice radiates empathy and solidarity with the Mediterranean Sea, and this empathy towards and solidarity with the more-than-human world always characterised his attitude and our discussions. He would passionately side with the web of life in our conversations on environmental justice: he wanted to be responsible and accountable to it directly, not to a human political system that represented a species he called ”an ungovernable exotic” that always hoarded resources to ”the human reproductive machine”.

We discussed empathy and what awakens it in people. We agreed that it had to be an embodied, particular experience because one can not convince another to feel for an animal, or an earthworm, or earth itself by rational arguments. For Newton, this kind of awakening had happened early in life, when he was driving along a highway in California, seeing the broken landscapes under constant, violent human excavation. Suddenly, he said, he could hear the earth screaming. From then on, earth was someone, not something.

He talked about his career becoming huge at the age of 88. There was no sign of slowing down, on the contrary: he didn’t want to make compromises or to scale his ideas down, but for the world to change, and his work to become more than a representation of what life on earth could be. He wanted it to be the real thing. Helen’s Town, a homage to Helen in the form of an eco-village with a production timeline of hundreds of years (because that’s how long it takes for trees to grow) was a serious dream and his frustration with curators who instead wanted something gallery size was palpable.

In 2020, when the pandemic had locked all of us in, I invited him to contribute a dialogue with me to a small exhibition I made about art, love, and relationality. My premise was that as artists our practice is always impacted by the relations that carry us, and our muses, whether they are human or more-than-human. In our dialogue, he talked about his lifelong work with Helen and their mutual excitement towards their work and life together, and how it was her who had initially led them to the question of climate change. And how everything that he did was and would be informed by her and their work together, and how her perspective still acts as a moral compass to Newton. Because, he said, ”Helen had the best ethical sense of anybody I ever met in my life, with one exception: Eleanor Roosevelt. So I put the bar high.”

I remain grateful for that Facebook message and that I had the honor of befriending this pioneering ecological thinker for these last years. In an email on the 10th of March, 2020, Newton wrote: “If possible I would love to democratize a little bit of hope in what

appears to be an ongoing and increasingly intense array of

catastrophes.”

We still have time to do just that.

Jamie Saunders

about the writer

Jamie Saunders

A resident of north Leeds in the Aire Valley, Jamie has worked in a northern local authority since 1992 as a public servant in local government working in strategy, sustainability and regeneration. He is a former trustee of the Permaculture Association (Britain) and a qualified futurist (MA foresight and futures studies, Leeds Beckett University)

Their work stands as a guide. When I remember, when I am provoked, they hold fast to more than the immediate concerns and less-than-life-enhancing work of day-to-day living. The life-web: see it, breathe it, hear it.

A life force for the life-web…

So, where to begin? With Newton, with Helen, with the Harrison Studio, with those ‘agent provocateurs’ and allies of those of us fortunate to have known them.

I can’t remember the first meeting, though this matters so much less than the essence of Newton, with Helen, through David Haley, creating connections across the Pennines. Teasing out a more ecological, more humane, and more progressive future for the North. A counter-point to the ‘business as usual’ of sprawl and expansion, into places and communities that could be woven back into ‘becoming’ as part of the life-web – as the Harrisons said, “every place is the story of its own becoming”. There it is again, that ‘life-web’. From ArtsTranspennine98 we saw a dragon emerging.

And I was ignorant of it in so many ways. It took the eco-artists from far away, the spirited and determined advocates to reveal, remind, and offer encouragement—and some serious challenge to personal choices and professional practice—to recentre on what really matters. “How big is here?” they asked. For a north in need of thinking deeply about the future ahead, and not playing catch up with that there London and the South or creating a ‘global mega-city region’ of 15m people, this continues to be a critical question.

We meet again many more times than I realise or really thought likely. Each time adding layers to thinking, linking the long past with the deep futures ahead: preferable, probable, possible, plausible. Trying to better understand the best and worst of the bureaucracy of local administration, of localised politics, of siloed and constrained professions, and disconnected communities.

Putting stewardship of place into place to work at the scale necessary for ecological regeneration and care.

Taking on ‘post-disciplinary practice’—with and alongside others—to do the research, to be commercial, to be life-enhancing. To do the work.

And gladly hosting Newton for an English Sunday lunch. And watching from away—as the global-local work of the Harrison Studio expands; from the glaciers, to the watersheds, from the meadows, to the cities, from the uplands to the top of the world. And back from the Pennines to the British Isles as a whole, responding to #astheseasrise. Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom—beyond the cleantech and the vested interests and out into the world of deep adaptation, of civic futures and the ‘force majeure’. Getting to grips with what co-evolution really means, over centuries, eras, epochs not just quarterly results, annual reports, and election cycles.

Albion, of many isles, is surrounded by water. As the fundamentals shift and we slowly, furiously, adjust to what is becoming. For our children, our grandchildren. To be more than good ancestors. At the heart of ‘sustainability’—reclaiming the concept from ‘financial viability’ and ‘sustaining the now’ to legacy and the global majority and the ‘more than human world’; of habitats, species, and dynamic complex adaptive systems.

So much more to be grateful for. So much more to reflect on, to embrace, and to share. Far more than ‘artists’, beyond ‘marketable self’ and galleries. Beyond ‘land art’ and environmentally-informed practice. Deep ecological advocacy of the living world. Of a world that will, as Gaia suggests, recalibrate with or without wiser human co-evolution. The American dynamism and bloody-mindedness are challenging, generous, and impatient with many. In later life, an elder when so many need such wisdom for their villages, towns, cities, and places to be post-industrial, post-colonial, post-normal. To be places where we live within the natural world; living well, with health, with care, and with a spirit that speaks to the best of us.

The world is a lesser place for the passing of Helen and Newton and their co-creation and collaborations with family, friends, and strangers. Their work stands as a guide. When I remember, when I am provoked, they hold fast to more than the immediate concerns and less-than-life-enhancing work of day-to-day living. The life-web: see it, breathe it, hear it. It is all around and in conversations, images, poems, and a deep body of work. The echoes and the opportunities remain.

Working through the ethos of life-web advocacy and stewardship may mean we can find the practical, imaginative, creative, collective means of living well in place. Testing out co-existence, beyond the ‘anthropocene’, and living more fully in the ecocene/symbiocene. The eco-art of Newton and Helen is as critical now in guiding those that follow in deep adaptation. Humane, bioregional, and planetary scales would be a fine continued legacy.

Ruby Barnett

about the writer

Ruby Barnett

Ruby (Ruthanna) Barnett, Studio Manager and Senior Researcher at the Harrison Studio and Center for the Study of the Force Majeure from 2017-2021. After earning her Ph.D. in Linguistics, she provided advocacy in housing and homelessness, debt, employment, and welfare. As a lawyer in Oxford, she specialized in immigration and human rights.

The Harrisons – Greater than the Sum of their Parts

The work of the Harrisons caused a shift that has enabled me to embrace complex systems in a more visceral, thorough way than in my previous work.

I worked with Newton from 2017 until 2021. In those first months, Helen visited the studio daily and I had the privilege of witnessing their deep love and tenderness. I traveled extensively with Newton and there is an inescapable intimacy accompanying a person in their 80s on long-distance travel. I prepared slides for talks, checked on his insulin supplies, laundered his clothes, drafted abstracts for conference proposals, and made sure his nose was moisturized.

Spending time immersed in the works of the Harrisons, as well as being part of the development of new works, has affected me deeply. My perception is forever changed. Newton liked to use Cezanne‘s Mont Sainte-Victoire series to speak on perspective but, for me, the work of the Harrisons caused a shift that has enabled me to embrace complex systems in a more visceral, thorough way than in my previous work. The form and non-form; the category of both-and; creating momentum, energy, from the oscillation between polarities. Understanding humanity as only one small part of the web of life, while at the same time comprehending the value of my own self-realization as an individual. The difficult and the charming. The tolerance and impatience. The compelling use of beautiful metaphor (“every place is the story of its own becoming”) contrasts with stark truths (“a tree farm is not a forest and tree farm floor is not a forest floor”). The duality is often shown as a conversation between elements—sometimes Newton and Helen themselves (Serpentine Lattice, Greenhouse Britain) or between others (the Lagoon Maker and the Witness in The Lagoon Cycle, the male and female voices in the Sacramento Meditations).

Inspiration for these arose from Helen and Newton’s ‘morning conversations’, developed after reading the Morning Notes of Adelbert Ames Jr., a scientist whose work was in vision and later in perception, developed a practice of setting a problem in his mind before bed, allowing his unconscious mind to work on it overnight and finding often that a solution had come to mind by morning. Helen and Newton experimented with this, conversing over coffee each morning to further elaborate ideas. In the later works, after Helen’s passing, Newton sought to call in her thinking, her voice, since they had actively worked to “teach each other to be each other” in the years prior, knowing that one may eventually be required to carry on the work alone.

The Harrisons knew that we can interfere, manage, or guide the life web only in limited aspects and that there may be unintended consequences. At the same time, choosing to take on the work, the only work of value in our urgent times, is balanced by knowing that all work addressing the continuing of the life web will by its nature be ennobling. It will change, benefit, and grow the one seeking to act. Helen and Newton’s fearless approach allowed them to face the stark reality of our likely future, and to plan pre-emptively, accepting some outcomes as inevitable. They maintained deep love, delight, and playfulness enabling them to model their vision and invite us to learn to “dance with the rising waters”. Helen and Newton’s lives and works embodied the whole being greater and other than the sum of its parts.

Beth Stephens

about the writer

Beth Stephens

Elizabeth Stephens, Ph.D., is a filmmaker, performance artist, activist, and theoretician. Stephens gained her MFA at Rutgers in 1992 and completed her Ph.D. in Performance Studies at UC Davis in 2015. She is the Founding Director of the EARTH Lab (Environmental Art, Research, Theory, and Happenings) at UC Santa Cruz.

Newton and I were friends. Unlikely friends, but friends, nonetheless. Even though we could not have come from two more radically different worlds, we somehow connected and got a deep kick out of each other.

I initially met the Harrisons in 2007 when I was the chair of the UC Santa Cruz art department. Newton called and told my department manager that he wanted to talk to me. At the time, I was aware of the work of the Harrison Studio, but I didn’t know their work nearly as well as I would. Newton was interested in helping the art department form a graduate program, and Helen was firmly retired from being involved in the UC system. My department had its sights set on creating an MFA—which we have since done—however, Newton and I became convinced that we should create a Ph.D. focused on Environmental Art. I even earned a Ph.D. from UC Davis because the UCSC administration told us that we couldn’t launch a doctoral program because no one in the art department had a doctorate. What a fun adventure!!

The first creative encounter I had with the Harrisons was in Green Wedding to the Earth, (2008) part of a larger collaborative project I created with my wife/collaborator Annie Sprinkle. This performative wedding took place in UCSC’s Shakespeare Glen. Newton and Helen delivered the wedding homily. They instructed me and Annie, at the end of their oration, “And now let us go to the mountains!” I did go to the Appalachian Mountains of West Virginia where I grew up. There I made my first environmental documentary, Goodbye Gauley Mountain: An Ecosexual Love Story (2012). That film has had a long and fruitful run. In fact, this morning, someone from Paris emailed me to see if they could screen it. Of course, I said yes.

In addition to work-related memories, I have fond memories of dinners with Helen and Newton, first at their son Gabe’s house. I was astounded and completely impressed when Newton told me he was building a new house at the age of eighty. He designed his house with wide accessible passageways, heated floors, a walk-in tub, spacious art studio, and a room for a caretaker. He built that house for Helen—and I remember the day he told me that Helen suffering symptoms of severe memory loss—likely Alzheimer’s. I watched as he took care of her, powerless to ease her suffering as she entered the last phases of her life. I admired the fierce but tender care that Newton gave to Helen, and I appreciated that he made it possible for her to stay home until the very end. The house that Newton built for Helen accomplished its job. It sheltered her until her death, and it accommodated her caregivers. It allowed Newton to keep doing the work he was compelled to create ― to try to help everyone see and understand the necessary steps to assist our ailing planet and to continue to nurture the “life web.” There I spent hours talking to him about the ideas embedded in his projects, entropy, saving the world’s oceans, and finally, channeling the Earth itself. Although we did not agree on everything, and sometimes we disagreed mightily, we were always able to move beyond our differences, come back to the table, and resume our talks again and again. That house also sheltered Newton in his final days.

Newton Harrison was brilliant, and I recognize the huge contributions that he and Helen made to the art world, and especially to environmental art. But honestly, it was those moments of eating together or hanging out on his front stoop, chatting with his neighbors, and petting various dogs that I miss the most. Newton and I were friends. Unlikely friends, but friends, nonetheless. Even though we could not have come from two more radically different worlds, we somehow connected and got a deep kick out of each other. We recognized in the other the desire to try to make a better world than the world that we had inherited, through art. As we watched the Earth sending out increasingly urgent distress signals our mutual recognition created a bond that we recognized and appreciated as we sat together on his stoop and watched his front-yard meadow grow. In a world where the electrifying speed of our lives is exhausting beyond measure, to have a stoop, a little meadow, and a friend to visit, and talk to about art, life, and the state of the Earth, is nothing short of a miracle.

Janeil Engelstad

about the writer

Janeil Engelstad

Janeil Engelstad is the Managing Director of the Global Innovation and Design Lab and an Embedded Artist and Lecturer at University of Washington, Tacoma. The Founding Director of Make Art with Purpose, Engelstad produces Social Practice projects that address social and environmental concerns around the world.

Helen and Newton Harrison: Re-imagining the Context of Art

At the center of their work was love and perhaps this is the greatest legacy that the Harrisons leave.

The following text recounts one of many experiences I had with Newton and Helen Harrison, as well as a sketch of their creative process. The Japanese term, kenzoku, which literally means family and the presence of the deepest connection, expresses our relationship and exchange.

In October 2016, Newton Harrison came to Seattle to participate in 9e2 Seattle (9e2), a festival that marked the 50th anniversary of 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering (9 Evenings). Produced by Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver, the original 9 Evenings was the first of several art and technology projects that would evolve into the non-profit group Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.). 9 evenings consisted of hybrid art performances and video, created by ten recognized artists working with some 30 engineers from Bell Labs performed at the New York City 69th Regiment Armory, from October 13 – 23, 1966. The performances were as much about the new technologies the artists employed to realize their work as the themes being explored.i In contrast, 9e2 examined contemporary themes impacting the way people experience life on Earth, such as climate change, AI, and social justice.

Conceived and produced by Seattle writer and cultural producer John Boylan, 9e2 was organized by a curatorial team from the arts and technology fields. Boylan’s purpose was three-fold: to teach and inform (the history of 9 Evenings was little known among the local tech and creative communities); to build connections between local, national, and international artists and technologists; and to explore ideas about how artists, technologists, and other creatives function in the world. “Underpinning this purpose,” Boylan recalled “were the questions: What are you doing? Why are doing it? How are you doing it and, to an extent, what does new art mean?”ii

As a member of the 9e2 curatorial team, I organized a handful of projects and programs, including a conversation with Newton. He was thrilled to participate, for this was an occasion for him to publicly reflect on his conversations with Billy Klüver around the time that E.A.T. was being organized.iii “He had it all wrong,” Newton recounted, “and I told him thus: artists and engineers should not be focused on creative experiments exploring the impact of technology on the individual and society. Rather they should focus on how technology can be of service to ecology and the planet.”iv The growing impact of climate change, Newton believed, had proved the relevance of the environmentally focused work he had produced with his wife and creative partner, Helen Mayer Harrison and the misdirection of Klüver’s focus.v Additionally, Newton appreciated that the larger purpose of 9e2 connected to the Harrisons’ inquiry into the meaning of art and art making in the latter half of the 20th century, as the impact of commerce, industry, and development on the Earth’s eco-systems were becoming more and more evident.

Throughout their careers, Helen and Newton cultivated a wide creative and scientific community and I would wager that almost everyone in this community could tell dozens of anecdotes like the one I shared about 9e2. Long-time academics, Helen and Newton naturally imparted their experiences, ideas, and wisdom through storytelling and conversation. They were also skilled at asking questions that moved and transformed ideas and thinking into deeper reflection and expanded consciousness.

At the forefront of environmental art and interdisciplinary, collaborative design and production, the Harrisons imagined and were utilizing design thinking before companies like Ideo and Stanford’s d.school brought the process into the mainstream. Making Earth, Then Making Strawberry Jam (1969-1970) begins with Newton’s growing ecological awareness and empathy for earth. Through his research, Newton learned that “the topsoil was in danger in many places in the world. So, I took the decision to make earth . . .,” he wrote about the project.vi

The Harrisons would invest months and sometimes years in the empathy phase of their projects. Researching and meeting with people who had expertise in the history, ecology, and politics of the place and/or problem that a project might address. They sought information and expertise from noted professionals, as well as people on the edges of mainstream thinking and from Indigenous people before it was politically correct to do so. Practicing deep listening, they had conversations with the Earth itself. Then, they would define problems in poetic texts that framed their initial research into inquiries, conversations, wonderings, and proposals, which they sometimes called think pieces, such as Tibet is the High Ground:

Thinking about the greening of Tibet approximately 772,000 square miles

Which is eighty percent of the 965,255-square-mile Tibetan Plateau

We imagined a domain that was about eighty percent savannah

And twenty percent open canopy forestFor a productive, self-sustaining & complicating landscape to develop

Bold experimentation becomes an absolute requirement

For instance with glaciers retreating

We imagined assisting the migration not so much of species

But of species ensembles that form the basis

For a succession ecosystem to form

That follows glaciers uphill

We then imagined a water-holding landscape

Where terrain was appropriate

And subtly terraformed so that rains

Stayed on the lands on which they fellIn order to locate species groupings

that would form the basis for generating

a uniquely functional future landscape

Where harvesting preserved the systemsAlso, drawing botanical information from the recent Pliocene

When the weather was the same

As that predicated in the near future

Taking on the problem of inventing an edible landscape

Which will be self-seeding and perennial

A landscape unique in its food-producing qualities

As the harvest preserves the system

And this kind of designing as endlessly repeatable

A green plateau can sequester 3 gigatons of carbon a decadeTibet is the High Ground, 2005vii

Rich with ideas, metaphors and instructions, Helen and Newton’s texts offer tutelage in communion; setting out on a course of action; prototyping, testing, then putting into place projects around the world; a handful that will continue well into this century.

At the center of their work was love and perhaps this is the greatest legacy that the Harrisons leave. Love of life, love of each other, love of people, and love of the planet. This value fueled courage and gave them the freedom to let go, experiment, and knowingly create work that would come to fruition after they passed. This letting go of ego, creating work where Earth was the client, was critical for the Harrisons and should be for all of us who wish to advance solutions that lessen the impacts of climate change and improve life for humanity and the planet.

* * *

i While a few performances, such as Robert Rauschenberg’s Open Score, were an indirect commentary on contemporary issues such as the Vietnam War, Klüver did not position his curatorial work on the impact of technology on society until the organization of E.A.T. About 9 Evenings he wrote: “It is important to realize (understand) that 9 Evenings was a realistic event. It wanted to achieve very specific practical and social goals. Its development was coincident in time with the spreading mysticism about technology, the McLuhan concept that the communication means were extensions of the body, the psychedelic experience as an element of art! 9 Evenings was none of that. (The artists and the engineers) were rigorous, energetic, and authoritarian and would demand completely controlled situations. That the forces behind 9 Evenings should have converged at that time, must have been separate from political developments of the global art, psychedelic kind of situation.” (foundationlanglois.org)

ii J. Boylan, personal communication, February 2023.

iii One of E.A.T.’s first activities was to organize loose, international groups of artists and engineers, by geography, to potentially collaborate with each other. Newton was an early member of the United States’ West Coast group.

iv N. Harrison, personal and public communication, October 2016.

v N. Harrison, personal and public communication, October 2016.

vi Harrison, Helen Mayer & Harrison, Newton. (2016). The Time of the Force Majeure. Munich, Germany: Prestal

vii Center for the Study of the Force Majeure. (2018). The Center for the Study of the Force Majeure. [Pamphlet]. Center for the Study of the Force Majeure.

Les Firbank

about the writer

Les Firbank

Les Firbank is a British ecologist specialising in the sustainable management of land, with a particular focus on European agriculture. He collaborated with the Harrison while working at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and then at North Wake Research, both in England. He has recently retired from his chair in sustainable agriculture at the University of Leeds, and is a member of the European Food Safety Authority panel on genetically modified organisms.

Our art/science dynamic was based on mutual respect and talking through different approaches to common questions, rather than the more usual multidisciplinary approach of artists seeking to illustrate the science.

For me, it was about the process and not the product, it was about the collaboration and not the outcome. I’m a professional ecologist (now retired) and first came across Helen and Newton when one of their helpers phoned me up one Friday afternoon to ask for access to some landscape data I had access to. If I had been busier, or if it had been another time of the week, I would have pointed her to our website and left it that. But I was intrigued, Why did you want them? She didn’t know but would get the project leader to call back. Newton called from Manchester and explained they were mapping the north of England. Quite why a Californian artist duo wanted to map England from a base in Manchester baffled me, so I went down to meet them and their team. They were working on the ArtTranspennine98 piece entitled Casting a Green Net: Can it be we are seeing a Dragon? piece, re-imagining the area between Liverpool and Hull. The eventual outcome was a series of hand-coloured large-scale maps of the region. Each showed a different aspect of the area, one with planned housing developments, one with nature areas, and so on. I wasn’t too impressed until I went to the exhibit, and watched people react to the work. They moved in closer and back out, walking from map to map, getting a sense of their area and what was nearby. It was like a GIS but required physical interaction and engagement. For me, the work was the fun. I met with people from the industry, regulators, and the arts, but unlike in most of my meetings, people were able to be open and honest about their thoughts, as it was ‘only’ an arts project. This allowed a level of communication not possible in more formal settings, where the participants have their ‘party lines’ to protect. Communities of practice were set up that persisted long after the project ended.

I worked with them again when I moved to Devon in 2007, where with David Haley we started a pilot project to design a sustainable village in the area. We set up a week-long workshop based in an agro-ecological research station in the region, enlisted an environmental GIS specialist Bruce Griffith, and set about our work. We made a good start to the work but, for various reasons, it did not really develop. The story can be found in a book chapter we wrote ‘A story of becoming: landscape creation through an art/science dynamic’ (Firbank, Harrison, Harrison, Haley, and Griffith. In Lobley and Winter (eds) 2009, What is land for? Taylor and Francis). Again, the pleasure was the discussions that addressed key questions which academics tended to shy away from, they were too broad. What do we mean by sustainability? How much carbon should one household have access to? Do we need livestock (yes!)? Was this really art? Before I had met the Harrisons I would have said no, this was ecology. But they taught me that anyone has the right to ask these questions and to seek and present answers, framed as they see fit. I framed my work in scientific papers, they used works of art. I used statistical tables; they used poetry and images. They are complementary, reaching different people.

Our art/science dynamic was based on mutual respect and talking through different approaches to common questions, rather than the more usual multidisciplinary approach of artists seeking to illustrate the science. Such questions have since become more widely asked, but tend to be answered too quickly, lacking in rigor. But I have tried to retain this questioning attitude and to pass it on to my students.

Tim Collins

about the writer

Tim Collins

The Collins + Goto Studio is known for long-term projects that involve socially engaged environmental art-led research and practices; with additional focus on empathic relationships with more-than-human others. Methods include deep mapping and deep dialogue.

Art and Change: The emerging social and ecological impetus

Artists have always critiqued and revealed belief systems, the program will teach artists to be effective agents of change. We seek to define the pedagogy of engagement.

A Dialogue from 2000 – with some edits and approval to publish from 2023.

Original Authors:

Jackie Brookner, Parsons School of Design, New York

Tim Collins and Reiko Goto STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, Carnegie Mellon University

Newton Harrison, and Helen Mayer Harrison Emeriti, University of California, San Diego

Ruth Wallen, Artist and biologist, San Diego

Josh Harrison, Director, Center for the Study of the Force Majeure, UC Santa Cruz

In 2000, we were engaged with the Harrison’s traveling to their home in San Diego with some regularity. Everyone involved in this discussion was struggling with adjunct, temporary, and year-to-year academic contracts. The Harrison’s proposed a dialogue which we might use to shape our individual and collective futures.

Art and Change Pedagogy

Philosophy: Nature as model, as measure, as mentor

Foundation Concept: Symbiosis and the biological imperative

Program: Ecologically engaged, Politically engaged, Socially engaged.

Emerging Issues: The public realm (social and natural) is in need of interventionist care. The visual arts with a history of value based creative-cultural inquiry are best equipped to take on this role. The long term goal, is to develop a cultural discourse which will:

1. expand the social and aesthetic interest in public space to the entire citizen body,

2. re-awaken the skills and belief in qualitative analysis (versus professional-quantitative analysis), and

3. preach, teach, and disseminate the notion that everyone is an artist.

The Problems: Artists are unprepared to take a productive role in civic discourse. Students graduate without the tools and bridging experience to allow them to learn the languages and process in the areas of ecology, politics, and sociology, and are therefore unable to enter into effective creative communication.

While information technologies is a burgeoning area of technical expertise, theory, and expression in the university setting, the emerging biological revolution is all but abandoned to the sciences. There isn’t a single department in the country with a program area which addresses the changing meaning of nature, restoration ecology, and bio-technology.

The traditional subject matter of art as well as the teaching methods taught in US art schools need an additional layering of information and training to expand the efficacy of an artists voice into these complex realms. Artists have always critiqued and revealed belief systems, the program will teach artists to be effective agents of change. We seek to define the pedagogy of engagement.

An Eco-Cultural Engaged Art: We propose a rigorous program of engagement training, providing artists with the theoretical and practical skills allowing them to productively engage the civic realms of politics and society with a primary focus on ecology/biology. In affect, we seek to transfer the language and skills which will allow artists to engage their colleagues in the professions of planning, design, and policy with equity and efficacy. Furthermore, to meet the challenges of a public realm increasingly challenged by private interests and legacy impact, the position of the artist will be defined in relationship to civic discourse rather than primary authorship.

The proposal includes a Graduate Major structure, an Undergraduate Minor/Concentration and a University Level Interdepartmental Credit Foundation Course. This was classic Newton, as he thought through the economics and the progression of creative/intellectual development which would be necessary for this new course of study. We can ‘hear’ both Helen and Newton’s voices throughout this proposal. We can also feel the love and care they put into this.

Johan Gielis

about the writer

Johan Gielis

Johan Gielis (1962-) is a Belgian mathematician-biologist, originally trained in horticultural engineering and landscaping. He has worked in plant biotechnology for over 25 years, with special focus on mass propagation and molecular and physiological aspects of tropical and temperate bamboos. In 1997 he discovered the Superformula, based on observations in bamboo.

A botanical Kepler and his Newton

What matters is not the individual forms, but how they are connected. Newton’s specific question was whether this would also teach us about ecosystems and continuity. He challenged and inspired me to look more deeply and broadly at ecosystems and our planet.

My work, which has its origins in botany, shows that shapes as diverse as starfish, flowers, squares, and cacti, the shape of atomic nuclei, and even our universe itself can be encoded in a geometric transformation called Superformula. So far, we have studied over 40000 individual biological samples, all of which are described by the Superformula; interestingly we found no circles or straight lines, the basic tools of our sciences. Our methods have now become a complete scientific methodology, with surprising new insights into how nature works and speaks to us. The attraction of the Superformula may lie in humanity’s need for a unified and continuous approach to life, nature, and our universe, as opposed to the discrete, random nature of our scientific worldviews.

What matters is not the individual forms, but how they are connected. Newton’s specific question was whether this would also teach us about ecosystems and continuity (he did not think the term sustainability should be used). He challenged and inspired me to look more deeply and broadly at ecosystems and our planet. How can we use these insights to “reshape and redirect the suicidal and ecocidal direction in which our Western civilization has taken us,” as Newton put it.

This is the direction I am currently pursuing with my mathematical friends. It is indeed possible to describe complete systems. The heart, once thought to be a pump, turns out to be a simple helical structure. Furthermore, the entire circulatory system combines the functions of transport with those of exchange, switching between a cylinder (for transporting blood) and a Möbius strip, a one-sided body for exchanging oxygen in the lungs and cells. These models should also work for ecosystems, translating holistic views into precise mathematics, as a language for the sciences and, he hoped, for the web of life.

Like nature, science is a never-ending endeavour, and what is cutting-edge today will be fossilized in the not-too-distant future. The Superformula is seen by many as the linchpin in this evolution. Another realization is that mathematics in its current state is a poor substitute for our deep knowledge. Mathematics is known as the language of science, the science of patterns. It is bad because it fails, as I call it, in its task of describing both patterns and the individual. With the Superformula, we can now study both the general and the particular, and link the discrete and the continuous.

After the publication of my article in the American Journal of Botany, many were excited by the idea of a unified description of the large and the small. This happened earlier in the sciences when the work of Kepler and Galilei inspired Isaac Newton to develop his System of the World half a century later. The American Mathematical Society wrote: “A botanical Kepler waiting for his Newton.”

How fortuitous it then was when Newton H. contacted me. It was not the Newton who would develop an updated world system or theory of everything based on my work. Instead, I got the opportunity to know Newton Harrison, a great artist and human being. However brief, our communication left a deep impression and will continue to be an important inspiration for my work in the sciences.

Ruth Wallen

about the writer

Ruth Wallen

Ruth Wallen is a multi-media artist and writer whose work is dedicated to encouraging dialogue around ecological and social justice. Her interactive installations, nature walks, web sites, artist books, performative lectures, and writing have been widely distributed and exhibited. She was a Fulbright scholar and is currently core faculty in the MFA in Interdisciplinary Arts at Goddard College.

Working in collaborative partnership, the Harrisons’ use of dialogue, with stories unfolding as they augmented or interrupted each other, amplified the generativity and generosity of their metaphors while spawning more.

“Somebody’s crazy, they are draining the swamps and growing rice in the desert…” “What if all of that irrigated farming isn’t necessary?”[i] I first heard Helen and Newton Harrison speak about their work at a lecture at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1977.

As a part-time art student, supporting myself working as an environmental specialist for the National Park Service planning office, the Harrison’s approach, distilling in-depth research into art-into metaphor, story, and performative activism―deeply affirmed my intuition to turn to art to promulgate an ecological ethic. They offered an enormously powerful example of employing art to raise crucial questions, spark imaginations, re-envision, and revitalize relationships between fragmented systems, and pose novel, ecologically sound approaches to environmental planning and policy.

Informed by their work, I received my first commission as an artist-in-residence at the Exploratorium. When I wrote to the Harrisons thanking them for their inspiration, they responded most generously, inviting me to come visit. Eventually, I moved to San Diego to study with Helen and Newton in the MFA program at the University of California, San Diego, (UCSD) and stayed in dialogue with them ever since, as mentors became dear friends, a relationship for which I am forever grateful. Of all that I learned from the Harrisons, perhaps the most important was the use of metaphor as a tool for thought. Influenced by the work of Lakoff and Johnson, the Harrisons understood that human thought is largely metaphorical and that the artistic imagination is crucial to identifying metaphors that can transform ecologies. Indeed, when I was a grad student, the creation of metaphor was a central concept taught in introductory art courses at UCSD. As ecological artists, Helen and Newton identified potent metaphors by listening to the wisdom of place, being attentive to the systems within which the place was embedded, and by naming the patterns that emerged, the configurations of relationships often exposed by studying maps. Maps revealed watersheds, the circulatory systems of the earth, a major subject of the Harrison’s work. Metaphors such as the Serpentine Lattice, or Peninsula Europe served as powerful devices to spark provocative narratives, shift conversations, and guide environmental policies. The Serpentine Lattice not only made visible the network of watersheds of the coastal rain forests draining into the Pacific from Alaska to northern California but through the lattice form identified crucial points to begin processes of restoration. Conceiving Europe as a peninsula highlighted the importance of revitalizing the mountainous spines that housed vital sources of fresh water. Working in collaborative partnership, the Harrisons’ use of dialogue, with stories unfolding as they augmented or interrupted each other, amplified the generativity and generosity of their metaphors while spawning more. The serpentine lattice could be funded through an “eco-security system,” like the social security system of the US. It is not surprising that the voluminous compilation of their work not only presents each project but tells the story behind its creation. Both the work itself and these stories contribute to the process the Harrisons termed “conversational drift,” which envisions their work alive in the world, seeding discussion. A visit with the Harrisons was always an invitation to think in larger terms. Indeed, their naming of the “force majeure” and the development of a center dedicated to its study, came out of their continuing quest. But having named the problem of our times, Newton’s last piece comes back to the simple principle that must guide human actions: “Every species, without exception, must give back as much or more than they take” ― a maxim that the Harrisons certainly took to heart.

[i] Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison, “Sacramento Meditations, 1977,” The Harrison Studio, accessed October, 2022. https://theharrisonstudio.net/sacramento-meditations-1977.

Petra Kruse and Kai Reschke

about the writer

Petra Kruse

Since 1984 work as art historian (PhD) and editor for various publishing houses and museums, among others, as deputy director of the German Bundeskunsthalle (Federal Hall of Fine Arts); responsible management of numerous international projects; since 2001 development of concepts, project management, budgeting, editing, design and production of exhibitions and books for public and private institutions worldwide together with Kai Reschke.

about the writer

Kai Reschke

Since 1982 work as curator, consultant, designer and organizer of exhibitions on numerous large-scale projects worldwide, many of them emphasizing on arts and ecology; since 1993 lecturing on book and exhibition design, planning, production, technology, didactics, and evaluation in collaboration with various national and international government agencies and universities; since 2001 development of concepts, project management, budgeting, editing, design, and production of exhibitions and books together with Petra Kruse.

From the very first moment the two of us met with Helen and Newton, we were convinced of their ways to work, and felt it to be very similar to the way we wanted ― and finally achieved ― to work.

Having known, been friends, and worked with the Harrisons for almost 30 years, we discussed, developed, and implemented many projects with them ― exhibitions as well as books: The most important one was probably The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years Counterforce is on the Horizon, a comprehensive retrospective of Helen Mayer Harrisons and Newton Harrisons work (published in 2016).

Thereafter, we took part in the activities of the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure, joined the board of directors, and founded a European branch of the center.

Most recently, we are involved in the development of Sensorium: The Voice of the Ocean, the last project initiated by Newton.

I, Petra, had the pleasure to meet Helen and Newton in 1994, when they designed ― together with their son Gabriel Harrison ― the initial Future Garden project Endangered Meadows of Europe.

The exhibition opened in 1996 on the rooftop of the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany in Bonn. As a leading member of the museum’s team, I had the privilege to accompany the process of developing this highly complex project from the very beginning up to its realization and the successive projects that derived from it.

To me, this work seems programmatic for Helen’s and Newton’s systematic approach, and it opened my eyes to the complexity and understanding of ecological systems:

Since an increasing number of agricultural areas are being maximized with regard to productivity or turned into building sites, meadows are one of the most endangered biotopes. A 400-year-old meadow from the Eifel area, which would have otherwise been destroyed, was rolled up, transported to Bonn, and unrolled on the museum’s roof. Collectively, the meadow contained 164 species of plants, among them several from the red list of endangered species, where normally there would be 30 to 35.

The roof garden of the museum had been mowed twice a year so that hay and seeds could be harvested which were then applied to more than 10,000 square meters of a meadow area along the Rhine and other places in Bonn: A Mother Meadow for Bonn: Future Garden 2 was created.

Since then, the concept spread, and many Future Gardens of different kinds were and are still being established all over the world.

I, Kai, first met Petra at the Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle in Bonn, where she was deputy director and I curated an exhibition on Alexander von Humboldt, the great 19th-century holistic scholar. She introduced me to the Harrisons in 1999 when the project Peninsula Europe appeared on the horizon.

There was no time to think about the exhibition itself but the development of a catalogue concept seemed practicable and above all most challenging:

The works conceived by Helen and Newton had so many entirely different formats that they could not possibly be squeezed into one book with a defined size without losing their integrity and comprehensibility.

Consequently, we developed a publication which, at first glance, looked like a book but when opened up consisted completely of adjustable foldouts with an individual size for each work.

The Harrisons were enthusiastic, the bookbinder was not ― and the result was convincing.

So was my first encounter with Newton. A vague feeling of being interrogated soon faded into the notion of having found some kind of ‘brother in spirit’ while studying and contemplating Humboldt’s theories and their essence that “everything is interrelating”: A true holistic thinker considering the arts as important as the sciences for communicating the central issues of human interaction with nature.

Petra and I had both reached a point of cognition with former projects where we had purposely been seeking interdisciplinary advice, but never in such a consequent methodical way as the Harrisons did combining a diversity of disciplines with different knowledge, perspectives, and approaches to collaborate and actually provide the basis for perceptions and results which an isolated individual could not generate.

From the very first moment, the two of us met with Helen and Newton, we were convinced of their ways to work, and felt it to be very similar to the way we wanted ― and finally achieved ― to work:

The permanent dialogue between the two of them;

The ability to find advisors, scientists, politicians, and other collaborators or supporters and form and maintain a powerful team;

To start a discussion and continue it without an end in sight;

To integrate new information into an existing concept;

To change plans, if necessary, without losing the objective;

To be convinced of and devoted to this objective;

To remain open and curious;

To never say: It is not possible.

Thus, a mutually beneficial relationship between the four of us started, developed, and remained more than close ― as Newton put it: We were their friends, designers, editors, and thinkers.

Salma Arastu

about the writer

Salma Arastu

As a woman, artist, and mother, I work to create harmony by expressing the universality of humanity through paintings, sculpture, calligraphy and poetry. Inspired by the imagery, sculpture and writings of my Indian heritage and Islamic spirituality, I use my artistic voice to break down the barriers that divide to foster peace and understanding.

I hear his voice when I read Channeling the Lifeweb again and again. The words echo in my mind every day and night.

I met Newton in March 2021 through my friend Heidi Hardin who was a student of Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison at UC San Diego in the early 70s. I was working on my project ‘Our Earth: Embracing All Communities’ which was inspired by the ecological verses from Quran. I published the book and Heidi Hardin arranged a Zoom meeting presentation about my book and invited pioneer Eco Artist Newton Harrison. I felt honored and was very grateful to learn that he has agreed to attend the Zoom meeting! I thanked Heidi Hardin for this great opportunity to join in conversation with Newton Harrison in this important talk “Women and Web of Life“.

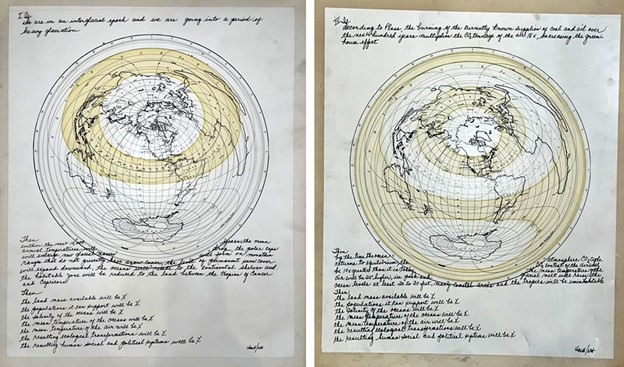

After that first introduction and hearing his encouraging comments, I emailed him my thanks and mailed a copy of my book too. He replied “Very interesting talking with you. I think you have an opportunity to engage your whole country using the Quran’s environmental positions to support your own or what you discover.” He shared his work, and we continued our communications through emails. He kept encouraging me by saying Female empathy and compassion must advance to save all life on Earth. He related an inspiring story of Helen’s compassion and dedication. He offered me to participate in the exhibition Eco-art Work: 11 Artists from 8 Countries at Various Small Fires in Los Angeles which was a great honor for me. I was given another honor to attend his surprise 89th birthday party on November 20th, 2021 with his close friends and that day I told him that I would like to visit him and meet in person. After that, he tried to schedule the time for my visit on March 24th, 2022 and, unfortunately, the cancer diagnosis happened, and the situation changed. I treasure his last email dated 5/17 when he sent me the image of his last work with these words:

“Thanks for your concern and good wishes. My treatments for the cancer have slowed me down. They are radioactive with added chemo. The course of treatment should end in about 2 1/2 weeks, and about 2 weeks after that I might be civil. Don’t want to lose contact. Very much hope things work out with your work and our gallery. Give me a call in about a month and I’ll see if I can’t make an afternoon with you. I am attaching a draft of my most recent work where I briefly become the voice of the Lifeweb, perhaps channeling in such a way that some of the stuff that I said surprised me after the fact.”

All the best, warm regards,

Newton

I hear his voice when I read Channeling the Lifeweb again and again. The words echo in my mind every day and night. My work after our meeting in March 2021 is totally impacted by his teaching. I have followed all projects executed by Helen and Newton Harrison, in particular through their book The Time of the Force Majeure.

I have found myself immersed in research to gain deeper knowledge in science and faith to find remedies to save our planet and its ecosystems. I have found underground network of mycelia that is regenerating, activating, and healing the damaged state of our environment and invisible tiny benefactors Microbes who are an integral and essential part of the web of life. Bridging Science and Faith creates a visual discourse that bridges science, religion, Islamic diversity and diaspora, language engaged with the plight of humanity, the soul, and the soil. Now my artworks juxtapose the ecological phenomena of interconnectedness through mycelial flow with concepts from the Quran as expressed through Arabic calligraphy and Islamic patterns. The new series mirror contemporary issues with possible solutions based on science and spirituality expressed through moving lyrical lines.

Aviva Rahmani

about the writer

Aviva Rahmani

Aviva Rahmani began pioneering ecological restoration as transdisciplinary artmaking in 1969. She authored, “Divining Chaos,” and co-authored, “Ecoart in Action” in 2020. Her “Blued Trees” (2015- present), focuses on how legal insights, expressed as art, can resist ecocide. Rahmani lives and works in Manhattan and Maine and is an Affiliate with the Institute for Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado, Boulder. Her undergraduate and graduate work was at CalArts and her PhD is from the University of Plymouth, UK.

We had parallel interests across many years, but they understood far better, how to platform and establish visibility for those interests.

I think the practical strategies I was testing, for how far simple ideas might become models for reciprocity and collaborative change, intrigued and inspired Newton. They both helped my career at many crucial turning points. Helen gave me my first job in the UCSD Extension in the late sixties and early seventies. In 1969, Newton asked me to form an ill-fated Dance Department at UCSD. He was an ardent supporter, assembling Eleanor and David Antin, and Pauline Oliveros to promote the project until politics shot it down. Newton and I had a more extensive and complex relationship than I had with Helen. Early on in my career, Newton sent me to connect with seminal art figures, whose collegial interests have remained my aesthetic lodestones in the extended art family I inhabited long after they all passed away: the collector, Stanley Grinstein, Allan Kaprow, who gave me a job as his TA and scholarships at CalArts and remained my mentor till his death, and the legendary gallerist Ronald Feldman. In our sometimes-volatile friendship, I was slowly provoked to aggressively carve my place in the art world.

Newton had a sculptor’s eye for form, which Helen deepened into a poetic narrative, serving them brilliantly in gallery and museum settings to frame concepts. He had a shrewd businessperson’s gift of the gab to narrate compelling visions to donors who allowed him to advance groundbreaking ideas in the art world. This, partnered with Helen’s pragmatism and diplomacy, also enabled advances in policy circles in Europe and the UK. Newton, and in a more muted way, Helen blended fierce competitiveness and professional generosity. Newton was intensely interested in two works of mine, Synapse Reality (1970), which made a social sculptural experiment of a small farming commune in Del Mar, California, and Ghost Nets (1990-2000), which restored a degraded former coastal town dump to flourishing wetlands on Vinalhaven Island, Maine. In 1970, Newton taught a class at UCSD on Strategies, anticipating the need Joseph Beuys also foresaw by forming the Green Party, to engage artists in international environmental policy.

In 2022, after decades of participation in the eco-art dialog (1990-present), I had co-founded, Newton curated and arranged the group show, Eco-art Work: 11 Artists from 8 Countries at Various Small Fires in LA. His hope then was to catalyze a market for the burgeoning international eco-art genre which might carry on the hopes they both had to change the world with art. It was only then that Newton seemed to me to be acting on understanding that the change they sought could only come from a larger community in which they were a part but not the center. It was a project that reflected an understanding of how complex the human parts are that might fit together to save humanity from itself.

Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison

about the writer

Helen & Newton Harrison

Helen Mayer Harrison (1927-2018) and Newton Harrison (1927-2018) were artists that pioneered art and ecology, developing an approach that characterised them also as educators. In their artworks, the Harrisons collaborated with planners, scientists, and communities on bioregional scale projects addressing ecosystem health in the context of climate change and the need for adaptation. Helen brought a perspective from her deep knowledge of literature, psychology, and education. She had held senior roles in Higher Education before beginning to collaborate with Newton. He had studied visual art and was already an acclaimed artist before beginning to collaborate with Helen. Their life’s work wove together these different knowledges and experiences, generating a unique and appropriate aesthetic that addressed the wellbeing of the web of life.

From Peninsula Europe: The High Ground – Bringing Forth a New State of Mind 2002

Is Peninsula Europe at a bifurcation point?

At a point of change and self-transformation?

After all, from the Romans through the Middle Ages

through the Renaissance

the Enlightenment

from Modernity to the Now,

that territory we call Europe

has many times rebuilt its landscape

economically, politically, culturally.

It has rebuilt its belief systems

and rebuilt its ecosystems.

Now we imagine a new set of emergent properties

suggesting that this is indeed a bifurcation point in a state of

becoming

a point of reorganisation of its own complexities

into a new form of entityhood.

If so

Peninsula Europe becomes the center of a world.

Peninsula Europe moves towards entityhood

when its boundary conditions become

more permeable

to what it understands

as contributing to its wellbeing

and

less permeable

to what does not.

Peninsula Europe moves towards entityhood

when its discourse

can focus on the carrying capacity of its terrains

for industry, farming, fishing

information production

and cultural divergence.

Peninsula Europe moves towards entityhood

as it transforms its wastes

into that which is useful and valuable

while successively reducing the wastes

that are damaging to itself

and when

its organic waste disposal

becomes a vast topsoil regenerating system

insuring green farming