The parks have been full; the ice cream vans have been doing a roaring trade; the tube has been unbearable. My hundred-year-old flat has a beautiful, large bay window in my bedroom, south facing, and the room has been stifling at night, making sleep difficult. I had special glazing put in 4 years ago, when I had the windows replaced, that is supposed to manage the solar gain but still the blinds and windows had to remain shut all day to try to keep the internal temperature lower. We dog owners have had to adjust the daily regime: no walking in the middle of the day, checking the pavement temperature, hugging any shade from trees and buildings. I even have a little paddling pool that I put in the garden with some water in for the dog, much to her initial bewilderment.

Many people this summer have been enjoying formal and informal opportunities to cool down by and in the water in London. We have outdoor lidos dotted across the city, as well as bucolic swimming ponds in Hyde Park and on Hampstead Heath. To the west of London there are swimming spots in the River Thames itself and there is an outdoor swimming club in the Royal Docks, east of Canary Wharf. It was heaven after running around London to slip into the cold, murky green water of Hampstead ladies’ pond where swimmers share space with ducks.

It’s not just the formal outdoor swimming spaces that have been full. We’ve been fascinated to find that a little corner of the River Lee became an impromptu bathing spot for humans in the heatwave, clearly with no thought to things like water quality or personal safety.

Through word of mouth and social media, Shadwell Basin near Wapping has attracted a growing crowd of young people, including my daughter, much to the chagrin of the local authorities. She was chatting with friends about how hot it was and how lovely it would be to find somewhere local outside to swim in the heat and someone mentioned Shadwell Basin. When they got there many other young people were there, jumping in and swimming, sunbathing around the edge.

In neither area was it clear that you shouldn’t swim there. They now have enhanced signage to warn of the dangers of swimming in these spots. [Informal swimming photo folder] In the prestigious development around Kings Cross, the water features have provided children with informal opportunities for play and other parts of the city with water features and fountains have been busy, parents bringing children fully kitted out to play, with towels, swimsuits, changes of clothes and picnics.

As well as these mostly joyous experiences of the heatwave, I’ve been worrying about the wider impacts—in the 2003 heatwave, there were 20,000 related deaths across Europe, with the elderly and vulnerable in cities most at risk. What will the figures be like this year? I’ve been working on themes related to climate adaptation in the urban environment for 11 years, but I’m not sure people (residents, professionals, public officers) are any more aware of how to adapt to extreme heat despite the millions spent on excellent research, for example the suite of projects under the UK Research Council’s Adaptation and Resilience to a Changing Climate programme, 2009-14.

Water is a challenge in extended heatwaves—reservoirs and rivers run low, drinking water has to be carefully managed, often resulting in hosepipe bans and other measures to reduce unnecessary consumption of a precious resource. Water is also a core part of health advice for coping with extreme heat —National Health Service heatwave guidance includes having cool baths and showers and drinking fluids, especially water.

So, a question for us all—if heatwaves and flooding are going to be more frequent and water is therefore at any one time a scarce resource to be conserved, flash flooding to be minimised, and an essential ingredient in dealing with extreme heat—are we doing enough to put water centre stage of urban design, regeneration and management? Are we actually designing new buildings and neighbourhoods with the future climate in mind? For London, this is likely to include more frequent heatwaves and more frequent heavy rain leading to flash flooding. I look at all the new homes being built in London—a high priority to deal with the shortage of affordable homes for families. Evidence of design for a changing climate—multifunctional green and blue areas, sustainable drainage systems, thought about orientation and materials—is scarce. The areas that do introduce these measures stand out as special, for example the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham and Groundwork project to “climate proof” social housing through sustainable drainage systems, monitored by colleagues in the UEL Sustainability Research Institute.

Many cities are like London, with different types of water bodies, from large rivers to small canals, creeks, ponds and ditches. Many of these water bodies are neglected and unloved, others are hotspots for regeneration, with developers often featuring pictures of water in their marketing materials. The opportunities for making the most of the water, through increased access, quality and enhanced biodiversity are immense. This is especially important in inner-city areas that have more blue space (water) than green space.

Rosie Markwick, a yoga and standup paddleboard (SUP) teacher, runs classes from the Islington boat club, a charity set up in the 1970s to offer water activities for local children. Islington is one of the densest and least green of the London boroughs and the south of the borough has been identified by the local authority as particularly challenging for climate change because of the magnifying effects of the urban heat island and the vulnerability of the local population. The Regents Canal flows through the borough, and the boat club is located on the City Road basin. Rosie teaches a wide range of people, from local 80-year olds to stressed city workers. She has noticed how people very quickly relax and become much more open and engaged when they’re on the water.

The Canal and River Trust, which manages 2,000 miles of inland waterways for British Waterways, including Regents Canal, has recently published independent research showing wellbeing benefits of being by inland waterways. This adds to emerging academic research about the wellbeing benefits of water in urban areas, such as the work by the Institute for Hygiene and Public Health, University of Bonn reseachers Sebastian Vőlker and Thomas Kistemann, and their 2013 research article “I’m always entirely happy when I’m here!” Urban blue enhancing human health and wellbeing in Cologne and Dűsseldorf, Germany, published in Social Science and Medicine.

The 2018 heatwave has shown how water has provided much delight and refuge from the heat across London. But, inevitably, the weather has changed and already the heatwave feels like a distant memory. But notwithstanding the ephemeral nature of this heatwave, it has been instructional for those city makers who will observe and listen. Rather than either ignoring hidden urban water bodies or just seeing them as profit-optimising development opportunities, we should invest in them for their health, biodiversity, recreation, cooling and social benefits.

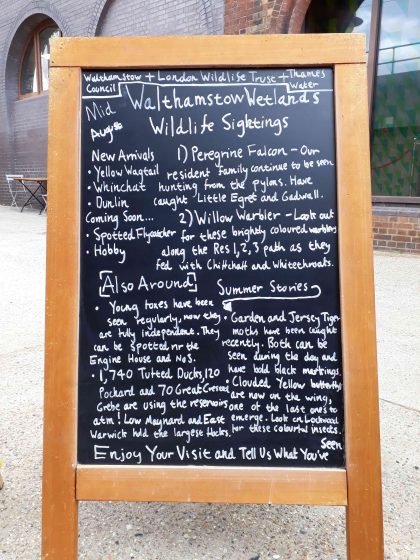

There are some great examples of things starting to change, led by charities—for example, Thames 21 and the London Wildlife Trust have both been involved in local projects to engage city dwellers in caring for and understanding local creeks and water spots as well as enhancing quality and access. Thames 21 has worked with Oxford University and local communities to identify a whole range of new opportunities for sustainable drainage and constructed wetlands. London Wildlife Trust manages wetlands in London, including Woodbury Wetlands, which is surrounded by a mix of existing social housing estates and new luxury apartments, as well as Walthamstow Wetlands, which I mentioned in my last TNOC essay.

Notwithstanding these positive signs, I would argue there is still a long way to go to optimise the benefits of urban water for people and nature. For example, there are also issues around increased demands for water in a heatwave. Whilst the urban food growing movement is literally blossoming in London, access to water in some of these spots can be difficult—a real challenge for successful cultivation.

In the heatwave, watering regimes have had to be stepped up markedly. My local mini-allotment site has had to get creative in finding a source of water, negotiating access to a water point in the street and running a hosepipe to fill water butts. Other growing sites have had to rely on residents bringing water from home—not a long-term solution.

Should urban designers in cities like London be looking for inspiration in cities like Seville or Cόrdoba, where hundreds of years ago gardens were created as tranquil oases, with water very much at their heart? Is that what has inspired places like Pancras Square, Kings Cross, with it’s flowing water feature? And can such thoughtful design be incorporated in less prestigious spaces where ordinary people live? Or would that be deemed unaffordable?

If such blue spaces can offer health benefits, surely they are worth the investment. Actually, there are places that have been designed with water as a key feature—new neighbourhoods in London such as Barking Riverside and Greenwich Millennium Village incorporate and link to water. It would be interesting to see whether residents are actively engaging with this local water and if it is bringing health and wellbeing benefits.

What would a design process that embeds water look like? There are many questions. Might it involve not only thinking about physical water bodies, their access, their quality, possible uses—for example, could they be swum in? Kayaked? Fished? Lived on? But also, how could water be managed locally for watering green or growing spaces. Is there potential for rainwater harvesting or grey water recycling, to reduce impacts of flooding? To provide delight and tranquillity? To provide local ecological richness and biodiversity? This type of process clearly requires many strands/disciplines to come together, deep partnership working, understanding local people’s needs and desires, thinking at different scales, and understanding what the trade-offs are between activities and functions, such as with regard to pollution or disturbance.

It seems to me that currently many of these questions are either not explicitly considered or are answered in isolation of each other. If we consider the fundamental role that water, and the water cycle, plays in our very existence and the life of the planet, maybe it’s worth the effort to attempt a more complex and comprehensive analysis of how we engage with water in our cities.

Paula Vandergert

London

About the Writer:

Paula Vandergert

Dr Paula Vandergert is a Senior Research Fellow in the Sustainability Research Institute, University of East London. She works with local authorities, strategic development organisations and local community groups on adaptive governance methods for sustainable and resilient communities and places.

Totally agree with Arnie- another very good essay my friend

Thank you Arnie, I’m glad you enjoyed it. I think there’s a great opportunity to rethink our approach to water in the city – hopefully the necessity created by the changing climate could foster innovation and creativity that leads to delightful and inclusive places for all to enjoy.

Brilliant piece – informative, interesting but also fun to read!