About the Writer:

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director.

Prompt

Urban sites gets planned. Urban sites get designed. Urban sites get built. Many of them are labelled as “sustainable”, or “ecological”. Are they so? How would we know? What do we even mean by the words sustainable and ecological, especially when put alongside the more common design descriptors relating to aesthetics and social function? Integrating these ideas suggests the need for various disciplines — ecology, landscape architecture, and planning, at least — to hash out the common principles into a shared understanding to advance evidence-based and ecologically sound design. Conversations like this can easily turn to certifications.

The Oxford Living Dictionary gives the following definition for the noun “certification”:

The action or process of providing someone or something with an official document attesting to a status or level of achievement.

A certification is a professional seal of approval, based on a set of professionally confirmed metrics. Indeed, we certify people for their expertise; there are certifications for organic produce; for fair trade coffee; and many more. And if we want to call urban sites that are designed to be “ecological” or “sustainable”, then we could certify these too. In theory, it would hold designers to a standard. It would give managers and policy makers confidence. It would put the ecology into ecological design.

That is, if we could actually agree on which underlying values and metrics should be built into such a certification. This is the conservation we are having here in this roundtable, and the responses are all over the map. What the specific metrics are, and at what phase of a project they should be applied — even whether it is a good idea at all — are offered in diverse and sometimes provocative answers.

Some examples of ecological design certifications already exist. LEED, owned by Green Business Certification Inc, has evolved to include more ecological and social parameters. The Sustainable SITES Initiative is a metric-based scheme that, according to their website, “ushers landscape architects, engineers and others toward practices that protect ecosystems and enhance the mosaic of benefits they continuously provide our communities…” There the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method — BREEAM — based in the U.K. Other certifications exist to focus on species or systems, such as Salmon Safe. There are some created by and for specific cities. New York has developed several certifications, including the Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines, or WEDG (“WEDG is doing for the waterfront what LEED® has done for buildings”, says their website). The always environmentally progressive Singapore created a Landscape Excellence Assessment Framework, or LEAF). [Note: This is not meant to be a comprehensive list, just an illustrative one.]

So, a number of certifications exist that are relevant to our theme, and each emphasizes a different but overlapping set of ecological and social parameters. Perhaps none are perfect, but all try to build some ecology into the worldview of design. Enough ecology? The right ecology? Do interdisciplinary teams lack a shared vocabulary? (Yes, as we discussed here in a previous roundtable.) What is needed to move froward?

We have gathered 15 designers and ecologists to talk about ecological design certifications. They were invited to celebrate or criticize existing systems, if they cared to. But mostly they were prompted to talk about the key principles and core metrics that would make the phrase “ecological design” harmonize the words ecological and design.

About the Writer:

Ankia Bormans

I came to Landscape Architecture by serendipity. I have many passions and perhaps the greatest passion is curiosity, as that allows me to immerse myself in the process without bothering or caring too much for the end result.

Ankia Bormans

Site analysis and evaluation in a developing country

Mechanisms for site analysis and evaluation have been developed, with the most notable that of SITES, GBC (Australia) and LEED (USGBC). The Green Building Council of South Africa have amended and adopted GBC and have adjusted the document to apply to the environmental and building legislation of South Africa. The document allows for the assessment of a building and more importantly the assessment of a green precinct.

In both the cases of SITES and GBCSA, the tools are relevant and useful but fall short when it comes to addressing the social and economic issues communities are faced within a developing country such as South Africa. These communities are often faced with more immediate needs, such as ensuring community safety, providing basic needs, developing sufficient public health systems, transport systems and education. These needs take precedence, often at the cost of ecological considerations.

Although there is a section in both SITES and GBCSA relating to the ecological rehabilitation of a site and the responsibility to healthy communities, it fails to address the issues when communities are already established and are in the process of being upgraded in situ.

It is understood that better ecological design will enhance and benefit communities, however pressing socio-economic issues often take precedence to the suggested ecological issues. This is particularly true in situations where immediate remediation is required in order for the community to benefit. Transport systems are a good case in point, where an immediate need to develop a sufficient transport system will take precedence over the rehabilitation of an adjacent river corridor or the upgrade of the stormwater run-off of an existing system. There are simply not enough resources to provide both, nor is there the time to develop an overarching strategy.

One can argue that this is exactly when an ecological assessment is required, but a strategy must be developed where the assessment of the site and the needs of the people can be accommodated without compromising one or the other.

There is a perception that taking a responsible ecological approach will miraculously change the way people respond to their immediate environment; that it will make a project instantly sustainable!

Questions remain. To what extent is the landscape (and inferred ecological responsibility) the appropriate tool to act as a catalyst to social change? What issues can be resolved or assisted through the change or upgrade in the landscape rather than expecting the ecological approach and upgrade of the landscape to be the miraculous answer to the complex issues facing developing countries?

As stated before, the issue is not merely to have a system of site assessment and ecological responsiveness, but how to act on, or within a site, remain ecologically responsible, and still take the needs of the community into account.

Sustainability should not only hinge on ecological factors but should take equality and accessibility and socio-economic factors into account. Perhaps a more sustainable approach would be to develop a strategy of assessment where it is ascertained how ecological considerations can enhance or assist in alleviating socio-economic issues.

More often than not projects or situations of this nature are in the public realm. Developing a strategy where ecology “dove-tails” with socio-economic issues the question around funding is also answered to a certain extent.

I certainly do not have the perfect answer, but feel the ecological assessment of urban sites is perhaps too reductive and do not address complexities in urban developments.

About the Writer:

Katie Coyne

Katie co-leads the Urban Ecology Studio at Asakura Robinson where she is a passionate advocate for design informed by studying the overlap between social and ecological systems.

Katie Coyne

Can an ecological certification help fix the critical problems in ecological design and Planning?

I hope not, and believe a carefully considered certification should be a catalyst for interdisciplinary collaboration, raising the bar for what we expect from ecological design and planning work. We should start the conversation about what to include in a certification by understanding the most pressing problems we’re trying to solve and prioritize from there. The following outlines are what I see as our prevailing problems in ecological design and planning today and how a certification could be a part of the solution.

1. Disconnection: There is a disconnect between scientists and designers in language, rigor, practice spaces, value systems, and access to research and literature.

If you say “transect” an ecologist will think you’re talking about field sampling, but a designer will think of a graphic, depicting variables across a spatial gradient. A lack of common ground in language translates to an inability to understand expectations of rigor across disciplines and exacerbates physical and theoretical disconnections between disciplines by creating gaps between scientists and designers even when they are both at the table. For scientists, learning to be “bilingual” means they need to be more willing to understand how landscapes hold different value for different people and that ecological value is only one piece of the pie. When designers understand the value of ecological knowledge informing practice, they are often met with literature so filled with jargon that it remains inaccessible because they often do not know how to translate technical scientific data into design principles.

2. Interdisciplinarity: There is a lack of expectation for truly interdisciplinary teams which translates to designs that do not maximize multifunctionality.

Design firms are becoming more interdisciplinary internally — a step in the right direction. Even so, scientists who practice within their field should be regular parts of design teams. Lack of interdisciplinarity means that teams miss opportunities for multifunctional design and favor focusing only on the functions the team is most knowledgeable about.

3. Scale: Many designs focus on sites but do not address neighborhood, city, or regional scales.

Landscape architects and planners are not collaborating enough with each other; and, ecologists are not expounding on the impact larger regional networks have on systems function. Many city policies promote site-scale sustainability but miss neighborhood to regional scales. Policies promoting green infrastructure (GI) decoupled from a city-wide GI plan result in piece-meal development of projects thereby promoting concentrations of GI rather than distributed networks and resulting in differential distributions of GI across socio-economic gradients.

4. Money: Even for projects with explicit urban ecological goals, there is typically not enough budget to pay ecological consultants as part of the design team or pay for monitoring before, during, and after project implementation.

All too often, academic expertise is expected to be provided free of charge and instead of these experts being integrated parts of design teams, their involvement is reduced to a single meeting. A limited number of informed clients willing to allocate sufficient funding for a consultant team to carry out rigorous research further exacerbates this problem.

All this considered, if an ecological certification is to be successful it must:

- Create a common language across multiple disciplines.

- Find a middle ground in expectations of rigor.

- Create universal metrics across disciplines that provide an accurate measure of project effectiveness against project goals and other projects.

- Create a forum whereby scientists and designers can regularly collaborate.

- Promote an understanding in ecological partners that ecological value is an equal part of a larger, holistic value set.

- Create an open-access database of academic research “translated” for non-scientists.

- Mandate the inclusion of interdisciplinary team members with verifiable expertise.

- Mandate that designs meet a minimum level of socio-cultural and ecological multifunctionality.

- Provide a certification opportunity for site, neighborhood, city and regional scales.

- Minimize the cost burden of the certification fee by creating a variable fee structure.

- Mandate that academic partners are equitably compensated members of the consultant team.

- Mandate socio-ecological research occur before, during, and after a design or planning process.

- Promote grant opportunities to help fill funding gaps.

- Emphasize that the certification, if fulfilled, will be more than just a trophy for a project but lead to greater resource efficiency, quantifiable benefits to the local community, and lower life-cycle costs to the owners of the project.

As an accredited professional with an existing certification program called Sustainable SITES, I can say that this program hits many of the key elements above, but not all. Most notably, SITES only certifies projects when constructed, leaving the possibility of certifying something like a neighborhood scale or larger green infrastructure plan unlikely, even if there are tangible results on the ground. LEED has a good precedent for what this model could look like with their LEED – Neighborhood Development certification. LEED-ND provides certification opportunities for new land development projects or redevelopment projects containing residential uses, nonresidential uses, or a mix at any stage of the development process, from conceptual planning to construction. Hopefully, SITES will prove to be the dynamic program it needs to be, evolving with practice and the input of its interdisciplinary supporters and critics, expanding its certification offerings to encourage rigorously designed landscapes across scales and contexts, and promoting more interdisciplinary conversations with designers, ecologists, and planners.

About the Writer:

Sarah Dooling

Sarah is an interdisciplinary urban ecologist, with 17 years of experience in urban ecology, social work, and wildlife management. She works on colaborative design projects and policy development efforts that integrate ecological design, environmental planning and social equity issues.

Sarah Dooling

Expanding the social Work of site design: Certification of design mentoring programs in LEED social equity credits

The development of cities is driven by politics and social prejudices that concentrate the creation of aesthetically pleasing and ecologically functional green spaces in wealthier neighborhoods. Site designs, likewise, are also value laden, indivisible from larger cultural and economic systems that generate inequities. However, site designs can also be tools that weaken dominant views that poor neighborhoods are negligible and that the future of community residents is pre-determined by poverty and insufficient opportunities. Many designers feel overwhelmed by the seemingly unstoppable power of speculative economics and underlying racist policies that thwart attempts among design teams to resist the machinations of urban development. One approach for mainstreaming a social justice agenda within the design process is to expand the existing social equity credits of performance-based certification programs, to include credits that award points for sustained relationships between design teams and under-served communities that create possibilities for vibrant futures.

Certification creates and enforces standards about the construction and quality of a given product. For the design professions, including ecological design and landscape architecture, certification establishes areas of expertise and skills required in making site designs. Landscape professionals have not historically been trained to integrate social equity concerns into site design plans. However, in 2014 the LEED certification program, which awards points for new construction projects for buildings and master planned neighborhoods, created three social equity credits. Last year, the Landscape Architecture Foundation published The Declaration of Concern which called for broadening the social impact of designs and mitigating root causes of degradation. Momentum is gaining to make the design professions ecologically and socially progressive.

LEED v4 social equity credits clearly broaden conventional LEED site performance metrics from building material selections and energy use to corporate cultural practices that recognize the up and downstream processes involved in creating goods and bads for people and the environment. The first credit focuses on corporate responsibility, and awards companies points if they pay the prevailing regional wage for construction workers and provide adequate safety training for workers. The second credit awards points to companies who develop a community engagement process to determine what the community’s needs are relative to the company’s project. Social responsibility in supply chains is the third credit awarded to companies that prioritize worker health and safety, uphold non-discrimination practices, establish grievance procedures and maintain a harassment-free construction site.

However, certification programs, including LEED v4, must go further in order to achieve truly progressive change in design and development practices. With a widening gap between the wealthy and the poor, the seemingly unstoppable devastation created by gentrification pressures and the unrelenting criminalization of people of color, design professionals must be creative and fearless in their commitment to creating equitable futures. What does “an equitable future” look like for an African American young man who stops attending an under-funded public school and helps pay his family’s rent with money earned by selling drugs? What does an equitable future look like for a community of mothers who worry that their children will quit school and end up in prison?

Expanding the social impacts of design means that designers become aware of and listen to community concerns. Certification programs, like LEED, have been criticized for promoting feature indicators over indicators that assess actual performance. For communities struggling with school-to-prison pipelines, the modification of the physical environment alone remains necessary yet insufficient for addressing root causes of poverty and racism. One possible approach is to establish Design Mentoring programs that partner with local public schools to work with students.

Mentors offer youth opportunities to learn design skills and to explore how modifying physical space can improve their own neighborhood. Youth offer mentors experiences about precarious living and the opportunity to understand that the future is about collaborative survival. The site design process becomes the point of departure for building relationships that heal and open up dialogues where we begin to know more about ourselves and each other.

Incorporating Design Mentoring Programs credits into LEED Social Equity credits legitimizes this broader understanding of the design process and performance goals.

Site Performance Goal: Cultivate a culture of leadership and self-respect within at-risk community youth.

Metric 1.1: Number of public school students involved in mentoring programs involving design team members.

Metric 1.2: Number of public school students who successfully complete a one-year mentoring program and admitted into a post-secondary degree program.

The Design Mentoring Program would require basic technical training, including computer design programs (e.g., InDesign, CAD), hand-drawing and model building. Students would be involved in discussions about project scoping and attend community meetings to observe the influence of political and cultural dynamics on design decisions. Design team members would sign a one-year contract for each mentee, and develop learning goals with the mentee. Participating students would present at the end of their enrollment in the Design Mentoring Program to mentors and clients. Equally important, design team members would publically present their experiences of working closely with their mentees to clients, parents and education administrators.

Creating a Design Mentoring Program is no easy task for design firms. However, such a program is an investment in the future of places and people for whom the future is bleak. Certifying something like a Design Mentoring Program mainstreams the expectation that design professions work to empower historically marginalized communities. Building resilient communities must start where people, and their biotic neighbors, are hurting. Establishing Design Mentoring Program credits establishes the site design process through which learning and leadership converge in the lives of community residents who have the most at stake in reversing the patterns of inequitable development.

About the Writer:

Nigel Dunnett

Nigel Dunnett is Professor of Planting Design and Urban Horticulture, University of Sheffield, UK, integrating ecology, horticulture and urban design.

Nigel Dunnett

I’m a botanist and ecologist by training and much practical field experience, but I live my life as a researcher, teacher and practitioner in the field of landscape architecture, and specifically in introducing green infrastructure into new and existing developments, often in high-density urban contexts.

In the UK, ecological certification (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method, or BREEAM), as applied to landscape developments rather than buildings, comes down to lists of species: it’s a tick-box approach, based on a complex formula that is based primarily on the number of native species included in a scheme. “Biodiversity” is the key word, and great weight is placed on this at the planning permission stage of developments. Of course, biodiversity itself is a rather meaningless and nebulous term, especially when non-experts are responsible for making planning decisions. Does it mean the total number of species, or does it mean how closely it meets target native plant communities, or is it all about very rare and threatened native species?

Current ecological science journals are filled with articles that are based on extreme quantitative approaches, mathematical modeling, and complex advanced statistics that are a million miles from the more descriptive origins of the science. While quantitative approaches are perfect for certification schemes that largely cover materials, life-cycle costs, energy performance, etc. for buildings, can the same sort of methodology be applied to dynamic, living systems? Too often, as in the UK example, ecological goodness is reduced to a tick-box listing of native plants — the fact that they are native (however that is defined) is seen as the key thing, regardless as to whether they are appropriate for that situation or not.

And this is the key point. The ecological environment in a city is usually far removed from that of the surrounding hinterland or countryside. Soils are highly disturbed, modified, or non-existent. On green roofs and other landscapes over structure, there is no contact with natural soils or geologies. Temperatures are elevated (often significantly so) through the heat island effect, and other microclimatic elements are also modified. It therefore makes so scientific sense whatsoever to insist upon native species of the region, or to look to plant communities that may be typical of the area, or to hark back to some pre-development ideal that represents what would have happened in a pristine world on that site, using the oft-cited argument that native species of the region are best adapted to the climate and soils of that region.

Furthermore, the true urban ecological plant communities that are truly adapted to local conditions, and fully site-specific, are the recombinant communities based upon easily dispersed species that can reach and survive on tough, inhospitable urban sites — and they are composed of alien non-natives that have found their home in the city, alongside native species. These novel ecosystems are truly urban, cosmopolitan, spontaneous, and hugely metaphorical in terms of having great cultural resonance. And yet they would never be recognized in “purist” ecological certification schemes as being a valid basis for high scoring.

I’ve worked on many projects where ecological certification has meant the removal of a wide range of species from the original proposals — species that would have brought huge ecological benefit in terms of pollinator resources, fruits and seeds, and many other benefits, purely on the basis that they were not native. I’ve been heavily involved with green roof schemes, where certification has insisted that “green roofs for biodiversity” are installed, following restrictive sets of rules, only to see them fail because plant species selection has been wholly inappropriate, again because of a purist tick-box approach.

One of the big problems with this method of certification is that ecological factors trump aesthetic ones. Where landscapes are visible and useable, they must work for people, not just for biodiversity. Ecological certification is definitely a good idea, but it must be enlightened and flexible. Basing it on species lists alone is not good ecology, and is a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of plant communities and of dynamic ecological functions. We need to move from the taxonomic idea that a plant community or ecosystem is composed of a standard list of species, to a functional approach, where it is the ecological functioning of the system that is of key importance. And we need to ensure that such schemes do not do active ecological damage in terms of the those processes and functions

About the Writer:

Ana Faggi

Ana Faggi graduated in agricultural engineering, and has a Ph.D. in Forest Science, she is currently Dean of the Engineer Faculty (Flores University, Argentina). Her main research interests are in Urban Ecology and Ecological Restoration.

Ana Faggi

Many cities around the world continue to be built with paradigms of the past that do not consider the challenges imposed by climate change, geological and geomorphologic constraints, soil quality, water sources, the loss of biodiversity and the homogenization of the landscape. An ecological certification for urban site design should guarantee that the project has considered the site as a living system. As such it could also help to create inspirational places engaging communities in valuing sustainable sites.

Therefore, an ecological certification should include indicators of natural patterns such as topography, drainage, soils, local weather, and vegetation to be layered on manmade patterns such as land uses, transportation and facilities.

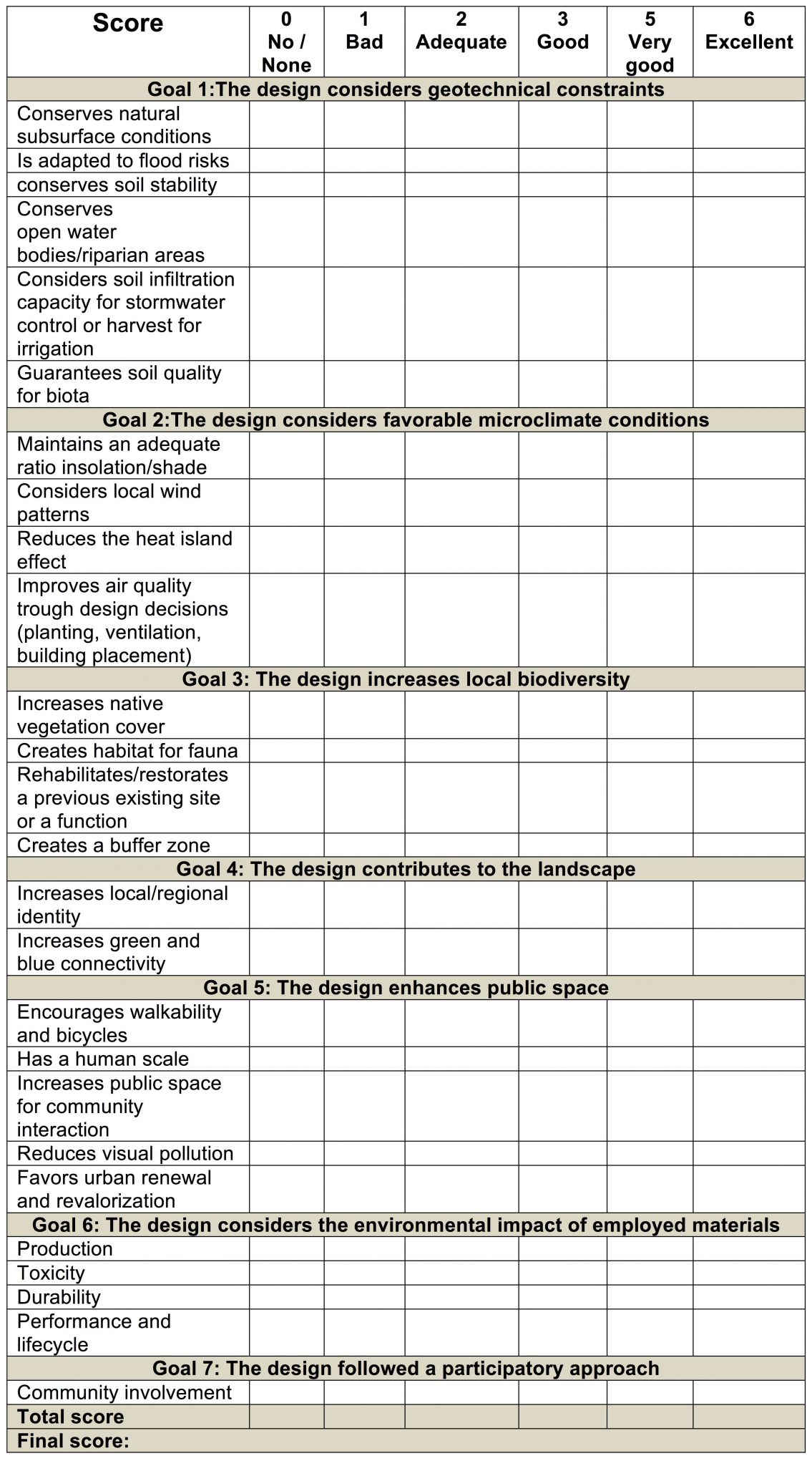

To develop an ecological certification framework one should set goals and define indicators to measure performance in meeting them. To pose an example, I present in the following table a checklist for a multi-scale assessment that allows assigning values to some variables discussed by Bry Sarté (2010) in his book Sustainable Infrastructure.

Following this example, an urban site could reach the environmental certification if it scores at least 52 points (26 variables x 2 [the score for adequate]).

Nevertheless, as each site and design are unique, variables should be discussed on site following a participatory process. Evaluating these resources as key design assets will help people meet important community values and help to protect those saving costs of impacts mitigation in the future.

In closing, one question that I want to pose is: who should be responsible for ecological design certification? The city council? Professional councils? NGOs? Universities? Who can we trust for ecological certification without making a project more expensive?

Bibliography

Bry Sarté, S. 2010. Sustainable infrastructure. The Guide to Green Engineering and Design. John Wiley & Sons,, New Jersey.

About the Writer:

Sarah Hinners

Sarah Hinners is a landscape and urban ecologist focused on bridging the gap between academic research and real-world planning and design applications. She is the Director of Research and Conservation at Red Butte Garden and Arboretum in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Sarah Hinners

I am generally skeptical of anything that involves a checklist, a point system, a prescribed set of “design principles” or “best practices”. At most, these things should be a starting point, not an end in themselves. On principle, I disapprove of any certification system where project planners and designers sign off and walk away, where a certification plaque is displayed somewhere and everyone goes home feeling good about themselves. I am an ecologist, and I know through the challenges of trying to convey the nature of ecological science the tenuous balance that exists between the broadly generalizable and the locally unique. Seeing the world through a lens of complex adaptive systems means that in every place nature, culture and chance events interact to produce an emergent social-ecological system that is different from anywhere else, despite the best efforts of national and international forces to make every place look the same. As the world changes around us at dizzying speed, I see the fulcrum shifting toward the local, rendering generalized recommendations less relevant.

We live in the time of a great social-ecological transition. All of the new human habitat we build for ourselves now should be preparing the next several generations for that transition and the post-transition world. Most of the certification systems that I’m familiar with (namely LEED and SITES) are focused on conservation of ecological resources and minimizing pollution. Wise use of resources and conservation of natural systems are a good and necessary step of course, but how does that prepare the next few generations of humans, other than making resources go a bit further? It just hands off the current maladaptive system, with a little less fuel to run it. What tools do they need? The majority of humans that now live within urban areas are disempowered: they are uninformed, disconnected, and vulnerable to disruptions in the complex global-scale networks of economics and infrastructure that support their lives. These networks are ultimately rooted in the biophysical world of our planet but ordinary individuals and households have essentially zero power to pull any levers to influence that system. (The power of the individual consumer as a market force is oversold in most cases.)

I argue that what the next few generations need from their human habitat is a combination of knowledge, connections, and options. That is, knowledge to understand what they see and experience, how the everyday world around them works, and their place in it. Connection, to place, to each other, to their community and to other living things. And options, to change course, to try something different, to fix something that isn’t working, to adapt to changing conditions. This is a social-ecological conceptualization of resilience in that it embeds the human designers and inhabitants of the built environment within that environment and within “nature”, particularly local nature.

Therefore, the questions I would ask (not the same as criteria but a step in that direction) are:

- Social-ecological integration: What human community is associated with this project and how is their ongoing relationship with this system integrated into the design?

- Knowledge: What knowledge or understanding will be enhanced by this project, particularly for its local human community?

- Connections: How does this project enhance social-ecological connections within the human community and with place?

- Options: How does this project build capacity for social-ecological adaptation?

One final question about certification programs concerns me. What is the moment at which certification is earned? Upon completion of construction (the norm)? One year post-construction? Five years? Fifty years? At the end of its lifespan, whatever that means? I think that certification should be given by the next generation, quite frankly, but this removes the incentive.

In the end, working as I do now in the reality of the present, I find systems like SITES useful as a reference point, and as an approach to starting a discussion that “speaks the language” of the current way of doing things. But no one should assume that by checking a certain number of boxes that you’ve done all you need to do to save the world, even one project at a time.

About the Writer:

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Mark Hostetler

Most development certifications, such as LEED Neighborhood Design, spend most of their emphasis, and point allocation, on design. For example, design points given for appropriate placement of built areas and conserved areas. This, of course, is important; one would want to conserve the most highly valued ecological areas. However, what occurs during the construction and postconstruction phases can ruin the ecological value of these conserved areas. Typically, no certification points or very few points are available to project components outside of design.

Construction impacts: In a development project, contractors and sub-contractors sculpt the land, installing transportation systems and building lots. Earthwork machines raise and lower grades to meet local building regulations. This whole process is an extreme disruption of the development site. For example, after a rain event, sediment concentrations coming from construction sites are often 10 to 20 times greater than runoff from agricultural land and 1,000 to 2,000 times greater than forest areas. A nearby, protected wetland can be heavily impacted from an influx of large amounts of sediment, chemicals, and other pollutants. As another example, large, ecologically significant trees may be marked for conservation, but construction activities can kill them. Trees and their roots are extremely vulnerable to construction activity. Vehicles that run over the root zone cause soil compaction, reducing the ability of tree roots to absorb essential nutrients and water. Around 80% of soil compaction occurs in the first pass of a vehicle. Fencing that is placed around the trunk of the tree is usually flimsy and not monitored. Where I live in Florida, heavy machinery is often parked beneath trees for shade.

Another critical issue during construction is how land clearing creates conditions where invasive exotic plants can gain a foothold. Many invasive plants are adapted to disturbance and when native vegetation is removed, and they are typically the first to spread into an area. Earthwork machines, which are transported from other construction sites, may carry invasive plant seeds and propagules to the construction areas. Once invasive plants gain access to a site, they can spread into conserved natural areas and displace native plants, ultimately impacting native plant and animal communities and ecosystem services. Careful monitoring and removal of invasive plants SHOULD occur during construction, but alas, very little attention is given in most certification programs.

Postconstruction impacts: Any sustainable development design can still fail depending on what happens during the postconstruction phase. The way people manage their homes, yards, and neighborhoods dictates how ecologically functional a development is over time. The list of inappropriate behaviors is quite extensive and includes:

- Excessive irrigation—Watering excessively draws down local groundwater supply, causing nearby wetlands to dry up. Also, overwatering causes an increase in leaching sending large amounts of pollutants to nearby streams, lakes, and wetlands.

- Excessive fertilization and pesticide use—Combined with overwatering, excessive amounts of nutrients and pesticides can enter waterbodies, causing a decline in water quality.

- Spread of invasive plants and animals—How homeowners manage their pets and decisions made on landscaping can have dramatic consequences for conserved natural areas. For example, free roaming cats can kill a surprising number of birds, lizards, and frogs. Released pets, such as Burmese pythons (Python molurus bivittatus), have caused extensive ecosystem problems (e.g., the Florida Everglades). If a homeowner purchased and installed an invasive-exotic plant (e.g., Coral Ardisia Ardisia crenata), this plant would may spread into natural areas and outcompete native vegetation.

- Replace native landscaping with exotics—Uninformed homeowners could replace natives with exotics and this would not only reduce biodiversity, but may also increase their use of fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation.

- Improper management of Low Impact Development (LID) features—LID features must be properly maintained by homeowners if they are to remain effective. Permeable pavements require annual vacuuming, swales and rain gardens should not be filled in, and cars and other vehicles should not park on swales. Lack of maintenance results in a loss of soil permeability preventing water from percolating into the ground.

- All-terrain vehicles (ATVs) and foot traffic in conserved areas—If people and ATVs are not kept on designated trails, they can disrupt wildlife populations and destroy native vegetation.

- Feeding wildlife and other human/wildlife conflicts—If people feed wildlife, wildlife species lose their fear of humans and can become a nuisance. Feeding alligators, raccoons, and squirrels may cause these animals to become aggressive. This is especially a problem with alligators, as their threat can be lethal.

- Conflicts with natural area management practices—For example, many natural habitats (e.g., longleaf pine uplands) are maintained by prescribed fire. If homeowners are not supportive of prescribed burns, these natural areas would revert to something other than what was intended.

While design is important, I believe a majority of the total certification points should be allocated towards construction and postconstruction issues. I conclude by listing several key construction and postconstruction practices (again, taken directly from my online article). These practices should be implemented by the built environment professionals and supported by appropriate certification programs.

Construction

- Reduction or elimination of turfgrass lawns. A number of native groundcovers and native shrubs and trees covers are available.

- Utilization of stem wall construction for houses. Often, fill dirt is required to raise the grade of a lot to meet flood requirements. However, when using stem wall construction, only the footprint of the home is raised by the required amount to meet flooding standards. The whole site does not need to be graded; conserving topsoil on a lot-by-lot basis.

- Establishment of clearly marked construction site access and routes that coincide with eventual streets and roads. This practice limits compaction of the soil to areas that will eventually contain roadways for the subdivision.

- Designation of parking and stockpiling sites for vehicles and building materials. Limit and clearly mark these areas so contractors know where to park vehicles, to mix materials, and to store materials. Riparian buffers, in particular, should be off limits to vehicles and construction activities.

- Avoidance of lowering or raising the grade around trees and natural areas as lowering the grade damages roots and raising the grade smothers them. Sturdy, protective fences must be installed at least around the dripline of trees.

- Regular construction equipment checks for invasive-exotic material. Establish an effective monitoring system to identify and eradicate any invasive species and also to clean machines before they enter a construction site.

- Construction and maintenance of silt fences. It only takes is one fence blow out to impact nearby wetlands.

- Development of environmental covenants and contracts for all contractors and subcontractors. In particular, contracts should clearly identify areas and landscape features that are protected; list financial penalties for contractors that damage these areas. Even bonuses could be included where contractors do no damage to protected areas.

Postconstruction

- Creation of strict Codes, Covenants, and Restrictions (CCRs) that address environmental practices and long-term management of yards, homes, and neighborhoods. These CCRs should describe environmental features installed on lots and shared spaces and appropriate measures to maintain these. An example of an environmental CCR can be found at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/uw248.

- Develop and install an on-site education program that includes educational kiosks along primary walkways and a web site that provides detailed information about local environmental and conservation issues (see example here).

- Establish a homeowner association that includes a sub-group to oversee conservation issues associated with built and conserved areas.

- Create a funding source to help with the management of natural areas. Funds can be collected from homeowner association dues, home sales (and resales), and the sale of large, natural areas to land trusts with some of the funds retained for management.

- Hire a landscaping company that understands environmental management techniques for shared common areas, such as stormwater retention ponds, forested areas, and riparian buffers.

About the Writer:

Jason King

Jason King is a landscape architect focusing on urban ecology, practicing at GreenWorks, blogging at Landscape+Urbanism, and researching at Hidden Hydrology.

Jason King

Made to measure: Rating system for ecological performance

Certification systems are valuable drivers of change in development, shifting paradigms by offering added value to developers and owners to differentiate their products from those that merely meet codes. That said, many of these certifications continue to be primarily building-centric, including LEED, Living Building Challenge, BREEAM, and One Planet Living to name a few. The focus on building performance is laudable and have raised the bar for energy use, indoor air quality, and water usage. Additional certifications such as Envision, STARS and Green Roads, provide non-building project certification for infrastructure and transportation. Together, these certifications provide opportunities to address sustainability issues in a systematic way, however none of these address ecology holistically, with often simplified metrics of open space and habitat.

On the west coast, Salmon Safe uses aquatic and ecosystem health for charismatic megafauna as the touch point for a certification system for parks, farms, campuses and urban sites. Focusing on water quality, habitat, urban ecosystem health, reduced use of chemical and pesticides, and proper construction practices, the system provides guidance for projects ranging from many acres to small parcels. Salmon Safe is unique in being less prescriptive, with guidelines for teams and that are evaluated by an interdisciplinary assessment team of experts in ecology, stormwater, habitat, integrated pest management (IPM), and landscape architecture convened as an assessment team to meet with project teams and evaluate success.

While SITES and Salmon Safe begin to address ecological issues, a true ecological certification, in the sense of one that measures actual place-specific ecological value, does not currently exist. The development of a good certification system requires the ability to both provide clear direction on expectations and levels of compliance with key targets and ensure a reasonably streamlined and consistent way to measure success. This is possible in ecological systems, but more difficult to translate into a metric that is widely adoptable or able to be simplified in a manner that is consistent from project to project. On one hand, a level of specialized knowledge would be needed to provide the necessary data to accomplish the measurements, for instance, using Shannon Diversity Index, conducting Floristic Quality Assessments. On the other hand, this level of rigor would ensure that projects employ a range of professional expertise (ecologist, wildlife biologists) to evaluate and measure pre- and post-development success in ways that are more scientifically rigorous. The certification system must also grapple with the dilemma of regional variation, with different bioregional variables that belie standardization due to the fact that most places have divergent ecological parameters.

At a minimum, the ecological certification system must:

- Be specific to the ecoregion and promote the key indicators that are unique to a local condition, such as key indicator species, unique ecosystem goals, and specific challenges. The place-based approach would need to employ reviewers that are familiar with the location of the project, and

- Have clear and measurable goals and objectives so users know the specific targets to achieve appropriate certification levels. This can take the form of a checklist approach, or a rating system via a number of points, or, use a less prescriptive approach, similar to Salmon Safe, using a panel of experts to assess project success.

- Be developed by an interdisciplinary team, including designers, scientists, planners, and engineers. This allows for vetting and cross-pollination of ideas from multiple fields, but also ensures a combination of rigor and applicability.

- While the challenges of creating such an ecological certification are not insignificant, the value in raising awareness and expanding our ability to measure project success becomes more vital as we address growing wicked problems. A true measure of projects with a focus on ecological health, and habitat value, provides key data in our strategies to address the impacts of climate change and resilience.

About the Writer:

Marit Larson

Marit Larson is the Chief of the Natural Resources Group (NRG) at NYC Parks. NRG manages over 10,000acres of natural areas including forests, grasslands and wetlands, stormwater green infrastructure and a native plant nursery.

Marit Larson

Two examples in New York City show how ecological certifications, or variants thereof, are being tested. One is the Waterfront Edge Design Guidelines (WEDG), which was developed by the Waterfront Alliance to promote a resilient and accessible waterfront in a city with 520 miles (840 km) of shoreline. A large portion of the city waterfront is continuously in some state of construction or repair, as aged infrastructure is replaced and industrial zones on the water’s edge are repurposed. Though WEDG does not focus entirely on ecology — other principles include equity, community input, and access — it provides a good example of an ecological credit system for design. After all, there are few locations in a dense urban area where ecological objectives are the only considerations. In WEDG, ecological design credits are associated with a range of design actions, according to specific waterfront types (residential / commercial; parkland; industrial). Some of the key ecological design components in WEDG include: conduct a thorough site assessment; avoid impact to existing habitat; remove artificial fill or structures; maximize habitat complexity; utilize native vegetation; plan for invasive plant removal and control; minimize stormwater runoff and maximize detention; and use natural materials.

A second example is the effort under way by the New York City Department of City Planning to update rules in the Special Natural Area Districts (SNAD), which were established to manage construction in environmentally sensitive areas. Special districts, which cover about 30 sq mi (78 sq km), were designated to preserve the diversity and integrity of native habitats, as well as neighborhood character. Over the decades, however, the outcomes for both protection of natural features and construction have been unreliable. To be successful, this planning effort needs to present clear criteria for design and construction that are not too onerous to follow, particularly for small homeowners making renovations.

The new SNAD requirements include key elements for ecological site design such as: assessment of current site conditions (wetland boundaries, vegetation communities, rare plants, invasive species, and other features); native planting that provides biodiversity, connectivity, and structural complexity; reduction of impervious area; management of stormwater; and invasive plant control. The applicant will have access to reference information such as site-appropriate vegetation community types, plants species lists, and priority planting locations that will facilitate the process for both applicants and reviewers. One question is how to ensure developers can access the expertise needed to develop and ecologically sensitive design, without posing an excess burdens, particularly to small property owners. An ecological certification process could eventually provide a resource to help landowners understand expectations and find expert advice.

Several common elements of ecological design from both these New York City examples can generate quantitative (or semi-quantitative) metrics. Hydrologic performance, for example, can be measured by a comparison of stormwater runoff at a site under natural vegetated compared to built conditions. Plant selection criteria can include percentage of native species, numbers of species, and forms of species. Use of natural materials can be evaluated in volume, or area. These or other metric can be compared across ecological certification programs over time to assess how effective they are in producing desired outcomes of protecting natural resource over time.

Two more key factors should be incorporated in urban ecological urban design — and in an ecological certification program. One is science and research: whenever possible, assumptions about what ecological benefit a specific design element brings should be tested and quantified. The other is planning for maintenance and adaptive management. In theory, a sustainable design requires little maintenance. In practice, however, in an urban area, many sites are vulnerable to environmental stressors, such as invasive species and pollutants, as well as disturbance — if not directly on the site then on adjacent sites, which can add to more environmental stressors. An ecological certification program can help assure that these factors, which are usually afterthoughts, are seen as integral to effective ecological design.

About the Writer:

Nina-Marie Lister

Nina-Marie Lister is Graduate Program Director and Associate Professor in the School of Urban + Regional Planning at Ryerson University in Toronto.

Nina-Marie Lister

Ecological Design-By-Numbers: Metrics for Success or Measuring Minutiae?

What is the measure of good ecological design? Is it in litres, degrees, and watts, or in happiness, heartbeats, and scent? Humans can establish measures for anything, and with it, as the maxim goes, we can know the price of everything and the value of nothing. Certification systems abound, and more recently, several new ones that establish criteria and associated performance measures for sustainability. But do they advance ecological design or fall short?

But none of these factors and measures tell us about the quality and impacts of design on the human user (and they certainly don’t address perceptions of non-humans). How should ecologically designed projects look? What responses should they evoke? How should they make us feel? Should they inspire? Create joy? Be beautiful? These outcomes are both the essence and the nuances of design; while related to performance, some would argue, the emergent qualities of design cannot usefully be reduced to, let alone assessed by a single measure. As Ursula Franklin wryly observed, that which is easiest to measure often reveals the least. The challenge for certification and rating systems that relate to ecological design for landscapes and living systems is to integrate rather than reduce. Akin to living systems themselves, a robust rating system needs more than performance measures — it needs monitoring and assessment of human use, the quality of changes over time, adaptation and regeneration, and yes, emergence through design. Such complexity is hard to imagine, and certainly beyond the scope of a single profession or discipline. Rather, it suggests value in exploring processes by which we design, e.g. embracing active transdisciplinarity to develop integrated systems of knowledge, evaluation and monitoring. As useful as it can be to evaluate and rate performance, much depends on which performances are evaluated, and to what ends. Measuring changes in human attitude and beliefs is more challenging than measuring behaviour for example — but these are often connected phenomena and the link between them is essential to learning, and certainly to adaptation and response. When we measure and assess human responses to ecologically designed landscapes (e.g. parks in our cities) we learn much that can inform and improve future designs.

Although SITES is grounded in broad principles of sustainability, like most rating systems, it is silent on the matter of how a landscape should look, how it should make humans feel, or the response it should evoke. Design, at its core, is the act of creation through deliberate direction and intention. In an ecological context, this act embraces the processes of life itself: unfolding, evolving and adapting. Surely this integrative act is more than the sum of performance measures. To be clear, SITES and other related certification systems are positive steps to mainstreaming sustainability through tangible projects and markets, while cultivating political and public acceptance of ecological design. In an era of climate change and a growing challenge to design with nature in our cities, the development of resilient public landscapes demands rigourous evidence-based design with effective performance measures. But arguably more importantly, resilient ecological design will rest on the nuanced and critical social assessment of human use and response to the landscapes that ultimately sustain us. Ecological design is a package deal: performance plus response — and that is more than a measure. It’s a long-term investment plus passion and care.

*Van der Ryn, S & Cowan, S. 1996. Ecological Design. Washington: Island Press.

About the Writer:

Travis Longcore

Travis Longcore studies nature and cities. He teaches students at the University of Southern California in the Master of Landscape Architecture and B.S. in GeoDesign programs.

Travis Longcore

Wildlife interactions should be incorporated into ecological site certification

To imagine an ecological certification for urban site design requires development or establishment of a normative definition for ecology. The study of ecology, in theory, is about understanding how interrelated systems work and does not set out aspirational goals, even though many ecologists have such goals. In everyday language, however, “ecological” tends to be used to distinguish a concern for other species and their habitats in addition to concerns that are more anthropocentric. In that usage, an ecological certification could be useful in that it welcomes and encourages consideration of other species and their needs within human settlements. It is necessary because one could have designs that are at the pinnacle of energy efficiency and yet are devoid of life and detrimental to other species (e.g., bird-killing glass boxes with no landscaping so as to avoid the water use).

For urban sites, an ecological certification that has co-existence with and promotion of native biodiversity could have many metrics. I offer three for this discussion.

First, bird-friendly design is essential, because even the most urban site will have some native bird species and could have more with some thought. The literature on avoiding bird deaths at windows is large and growing and detailed guidelines are available and have been adopted by major jurisdictions in the United States. Once collision hazards are addressed, site design can encourage bird use through provision of native plants, which provide needed food in the form of insects, seeds, and berries. Bird conservation science now identifies survival during the migratory period as critical to the future of many birds of forests and grasslands and designing bird-friendly cities is one way to help conserve birds across the continents.

Second, sophisticated guidance for reducing light pollution is needed in a manner that recognizes how differently other species perceive and react to light at night compared with humans. An ecologically certified site would minimize lighting to the times and places necessary, use the lowest possible illumination necessary, and avoid the shorter wavelengths of light (blue, violet, ultraviolet) that contribute most the physiological disruption of circadian rhythms and alterations in behavior such as insect attraction. “Dark-sky” recommendations are a good start in this direction, but are insufficient to address ecological concerns.

Third, any ecological certification of an urban place needs to have an enforceable set of regulations that govern interactions with wildlife. Urban wildlife specialists have clear recommendations that designers and project planners should incorporate from the start. For just a few examples: do not use anticoagulant rodenticides (they kill mammalian and avian predators); do not use neonicotinoid pesticides (they kill pollinators and birds); do not allow feeding of mammals (that includes unintentional feeding through unsecured trash and intentional feeding, such as feeding outdoor cats, which increases their concentrations and results in conflicts with predators such as coyotes); and remove stray and feral animals. Long-term ecological value depends on how a site is managed, and designers and planners can build that management into the site and set good standards at the outset.

These and other elements as a certification could provide benchmarks for designers to design better for native biodiversity in cities in a way that I believe would measurably improve outcomes in this area over other available certification schemes.

About the Writer:

Colin Meurk

Dr Colin Meurk, ONZM, is an Associate at Manaaki Whenua, a NZ government research institute specialising in characterisation, understanding and sustainable use of terrestrial resources. He holds adjunct positions at Canterbury and Lincoln Universities. His interests are applied biogeography, ecological restoration and design, landscape dynamics, urban ecology, conservation biology, and citizen science.

Colin Meurk

The profession of ecology is in a state of crisis — dismissed often as the preoccupation of “greenies” and “tree-huggers”, and yet an ecological lens and ecologically informed decisions about managing the planet and urban environments has probably never been more crucial. Ecology brings a particular holistic approach to analysing issues and problems and devising innovative, joined-up solutions. As they say, some of my best friends are landscape architects, ecological engineers, planners, environmental lawyers, etc., but unfortunately, at least in New Zealand, ecology is not part of their curriculum. And yet these other professions have largely usurped the role of ecology in urban planning and design with their powerful mantras of control, order, safety, colour, fashionable imagery, public health, and 3-D fly through graphics.

This is a slight deviation from ecological certification, but it is one thing to be certified, and quite another for there to be a protocol/rule/law in place that requires ecological input as an equal partner with the other pillars. This is a “metric” that needs to be applied to city hall and business rather than to ecologists. That is, decision-making bodies that evaluate or permit land management, natural values, development, etc., shall have equal representation of business/economics, sociology (in the broad sense, including cultural considerations and aesthetics), and ecology (may include environmental engineering but must have an experienced, ecosystem scale ecologist). Once this is achieved, we can be confident that more integrative, inclusive and sustainable decisions will be made.

So the first solution for competent decision making is for a certified ecologist to be a required member at all board and governance tables—to spot the risks and define the opportunities at an early stage of planning, to save wasting resources and to capture benefits. Ecology should be the hand-maiden of all site evaluation (making sure there isn’t some rare thing being sacrificed for someone’s “amazing” creation), planning, design (using appropriate species in appropriate/sustainable ways), AND implementation. Having an ecologist on all boards is not pretending that they are “neutral”, but it is acknowledging that the business and social representatives aren’t neutral either. It is critical to have an advocate defending all the values at the co-creation stage, not as a “nice-to-have” after thought.

Certification: Boards and clients need to have faith in the integrity and knowledge of the professionals working for them. So some standards are needed. New Zealand does have ecological members of environment courts, but more often than not they are people who have a good understanding of environmental law rather than ecology per se. Maybe I can elaborate on their standards later.

Criteria: Apart from having holistic credentials and expertise in given subfields of ecology, there is a need to demonstrate that one is capable of considering, evaluating and accommodating a broad cross-section of values and needs, and importantly is widely networked to all the sub-disciplines so that opinion can be sought from other appropriate expertise when required. Well, that sounds a bit like the gate keeper again, but at least it is a little closer to the coal face. Attention to minutiae as well as the big picture is essential, as is understanding the difference between a natural ecosystem and a restored or offset one. I’m somewhat protecting my own situation here — decades of experience (based on careful observation of nature in my own country and internationally), but inevitably old school in terms of modern statistical techniques. It seems that paper qualification is one measure, but years of (field) experience should also count.

So, paper qualifications, at least 5 years of field experience (perhaps engaged with community groups), publications, demonstration of wide multi-disciplinary networks, and references from peers and former clients/employees should be in the mix.

About the Writer:

Diane Pataki

Diane Pataki is a Professor of Biological Sciences, an Adjunct Professor of City & Metropolitan Planning, and Associate Vice President for Research at the University of Utah. She studies the role of urban landscaping and forestry in the socioecology of cities.]

Diane Pataki

Just the other day I was in a dissertation defense quizzing a student on the definition of the term ecology. This led a colleague from another discipline to suggest that ecological scientists should stop claiming “ownership” of the term ecology, since the word is now used by many different groups to mean many different things. That’s the first issue that comes to mind when thinking about the question of ecological certification. It’s undoubtedly true that even within the intersecting fields of urban ecology, planning, and design, “ecological” means different things to different people.

Which brings me to my first concern about ecological certification:

1) We’ll actually have to agree on what we mean by ecological

Sometimes the term is highly normative, meaning something that’s more “natural” in some sense and therefore basically “good”. Scientists tend to bristle at the suggestion that a particular ecosystem can be “good” or “bad” (although if you scratch at the surface there’s a whole value system embedded in even the most “scientific” ecology). Similarly, my colleagues from the social and environmental sciences often use words like “interconnectedness” and “holistic” to describe places and ideas that are more ecological. This bears some relationship to the ways in which scientists envision ecology at the systems-level, though still, sometimes these words also give me pause, scientifically. Is everything really connected? Everything, in a literal sense? If so, it might be a tall order to understand all of these connections, and an even taller order to account for them explicitly in site design.

Nevertheless, there is some commonality across disciplines in the idea of systems interconnected with each other, and with the outside world. So one element of an ecological certification would probably be about connected-ness, both internally and to the external environment. Understanding how a site is connected to outside systems such as air, water, wildlife habitat, other natural resources, and hopefully the wellbeing of people is tractable, and could bring together several uses of the term “ecology”.

2) We need to talk about who gets to decide what’s important, and who’s willing to decide

This connectedness component presents its own problem though, in that some kind of prioritization is necessary to decide which relationships we should focus on. It’s not uncommon in certifications to generate some kind of checklist that contains all of the possible options we can think of, and then to let someone else decide what’s important: some group of stakeholders, clients, policymakers, or “the community” (which opens up a host of questions about how and why certain members of the community were consulted).

My colleagues on the social science side of the aisle are also quick to point out dynamics of power that determine who gets a seat at the table in deciding the components of ecological certification. The regulatory environment is hugely influential as well. In my experience in U.S. cities, environmental initiatives are still heavily influenced by the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, and their accompanying mandates to meet standards for the criteria air pollutants and Total Daily Maximum Loads. These were both critically important pieces of legislation that should be protected (as they are currently in some danger).

However, they’re also more than four decades old. It’s striking to me that in the last 45 years, we’ve made relatively little progress in coming to a consensus about basic metrics of environmental standards that facilitate human health outside of these federal mandates. Even coordinated efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are stalled in the U.S. at the federal level (though admittedly much less so in the rest of the world). Perhaps the accelerating political actions of U.S. scientists responding to federal inaction will finally spur some scientific consensus on environmental metrics and desired outcomes that government mandates cannot. Because while many diverse stakeholders and community members must have a say in developing an ecological certification, scientists need to speak up too. These days it’s ineffective at best and dangerous at worst to wait for someone else to generate the checklist for us.

3) We need to be willing to do this the hard way, not the easy way

So that said, I think full greenhouse gas accounting needs to be part of an ecological certification. While many carbon accounting protocols have been developed for regulatory purposes, urban landscapes have unique issues that differ significantly from, say, avoiding deforestation in the tropics. In my opinion, too many projects seek to claim carbon “credits” either formally or informally by adding up the things that are easy to add, such as carbon contained in soils and trees.

But the climate system is not a carbon calculator. It sees everything: the fossil fuel emissions generated by an offsite nursery to grow the plants; the energy used to pump, treat, and spread irrigation water; the energy consumption and nitrous oxide emissions associated with inorganic fertilizer; and the emissions associated with excavation, transporting equipment, and maintenance.

If we want to promote sites that really contribute to solving climate change we need to do full life cycle accounting of landscapes, in the same way that the full life cycle of products is now commonly accounted for. It will take more information than is generally available for most projects, but it’s still tractable, and it’s the only way to know we’re making real progress in meeting climate goals through landscape projects.

About the Writer:

Mohan Rao

Mohan S Rao, an Environmental Design & Landscape Architecture professional, is the principal designer of the leading multi-disciplinary consultancy practice, Integrated Design (INDÉ), based in Bangalore, India

Mohan Rao

Ecological certification for Urban Site design – a really bad idea!!

The idea of a certification or rating is premised on the hypothesis that there is a single perfect solution against which a given intervention / proposal is weighed. One has to only examine the well-meaning but misplaced idea of certification prevalent in buildings. Focused on efficiency, the system has effectively flattened the very nature of built environment across the globe. In its efforts to standardize, the system has not only become highly prescriptive, but more dangerously, has reduced all built form into simplistic templates.

In other words, if the intent is to mimic LEED-like certification for ecological performance, then yes — it is a bad idea. However, if the intent is to enable a framework for assessment of site level interventions for their ecological performance, the way to go would be creation of comprehensive benchmarking processes as against a mere certification akin to LEED. This is all the more critical given the negative experience of building certification.

An ecological evaluation process would have three necessary characteristics: diversity, prioritization, and temporality; aspects entirely missing from processes such as LEED.

Diversity is obvious, since the process needs to address the immense diversity of ecological processes. Even assuming that this would not be a global standard but one tailored to each country / region, the process would still encounter a wide variation in ecological parameters. One can see immense variation in soil quality, stratification, topography, etc., between sites separated by even a few kilometers.

Prioritisation is a bit more difficult since it may not be strictly objective. Even within a small geo-climatic context, behavior of natural elements and their interaction with each other is complex and varied. For example, a standard framework like zero-discharge cannot be universally applied across contexts. One will have to go beyond urban drainage demands and factor in ecological base flows upstream and downstream and to address capacity and resilience. The other aspect of prioritization comes to the fore when socio-cultural layers are laid over the site and context. The process should allow for subjective prioritization of issues based on both the natural and development context of the site. While not strictly technical, these parameters often determine the success or failure of an intervention.

Temporality is the ability to be able to not only interpret the process and outcome but also allow for dynamic changes in the system’s behavior over time. For example, one may develop a “manicured” landscape as a short-term measure to address erosion and dust but the desired outcome in the long term may be a gradual progression to natural landscapes. It is important to note that unlike building centric rating systems that are concerned with a product, an ecological evaluation process has to address the behavior of and changes in a natural system over time. Temporality becomes all the more critical if one has to integrate climate change challenges over the lifecycle of the intervention.

The ecological benchmarking process should necessarily address three broad aspects: Capacity, Flows and Resilience.

- Capacity, or Natural Capacity, is the intrinsic capability of the system for generating, sequestering and/or recycling a given resource. This will be a factor of both geological and atmospheric agents to establish capacity of the site with respect to critical resources: water, biodiversity, nutrition, carbon, micronutrients, etc.

- Resource Flow captures all the resources that are part of the natural system including key elements such as carbon, phosphorous, nitrogen, etc.

- Resilience of the system maps key parameters likely to render the system vulnerable and disrupt its equilibrium.

The central idea of the ecological evaluation process would be to ascertain the changes in natural processes of the site and the extent to which the final product would enhance, support or disrupt these processes. Only when the benchmarking process is well established can the proposed intervention be evaluated for its impact on the site. This would imply a non-linear evaluation of each aspect of the development, unlike the silo approach seen in LEED-like rating systems. Based on the need, context and expected outcome, the intervention can be evaluated for overall performance. It is important to distinguish from conventional rating processes where above-average performance in one criterion can be offset by suboptimal performance in another (extremely good energy efficiency with very low water conservation, for example).

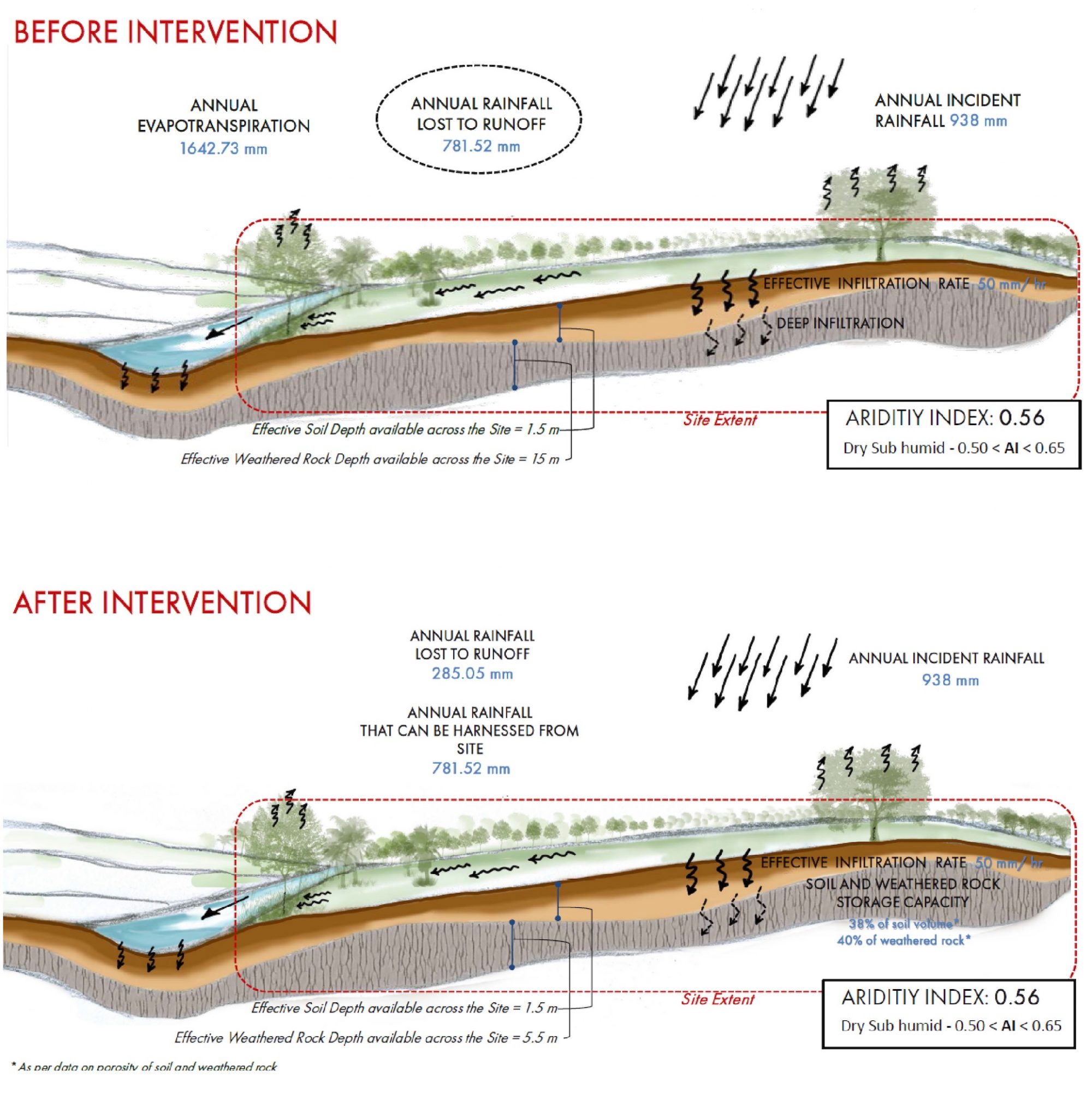

A critical difference between an ecological evaluation and LEED-like rating systems would be the benchmark. While building-centric conventional rating systems rely on the norm or business-as-usual models for comparison, an ecological evaluation system would derive benchmarks based on natural processes. An intervention would be evaluated for not how it compares with other conventional developments but on the degree of change it brings to the site in its natural state and manner in which that change is managed.

To illustrate one possible way in which ecological ratings may be actualised, one could examine water. LEED-like systems rate an intervention based on the idea of efficiency: reduction in demand, extent of recycling, quality of wastewater output, water harvesting, etc. The entire understanding of water here is one of demand management within piped networks. An ecological evaluation would encompass the complete water cycle: precipitation, run-off, atmospheric humidity, soil moisture, deep aquifer, fossil waters, embedded water in biotic systems, etc. The evaluation process would use the natural capacity of site and systems towards resource management and establish a baseline against which the proposed intervention is examined. The three characteristics of the benchmarking process — diversity, prioritization, temporality — will help address the changed hydrological cycle within the given context and develop strategies based on site specific priorities and over time. It should be noted that unlike LEED-like systems, development strategies are neither static nor dependent on the nature of development (industrial, housing, etc.), but are dynamic and defined by the intrinsic natural capacity of the site. (A part of this process is illustrated in the image below).

To address the original provocation — of ecological certification as a bad idea — the focus is on evaluation based on rigorous benchmarking of ecological processes and not comparative ranking and rating of interventions. Terms like rating, ranking, and certification need to be replaced with evaluation and benchmarking. This is not merely pedantic nitpicking but an important step towards reimagining both the process and outcome.

The process outlined above is by no means comprehensive or conclusive. It captures some of the essential elements I have used in my own work across diverse geographies over the last two decades. And it should be pointed out that the framework undergoes continuous changes when applied to a new site!

About the Writer:

Aditya Sood

Aditya Sood has a diverse research and professional experience in water resource management, civil and environmental engineering, and in software development. He enjoys hiking, bird watching, photography, and occasional dabbling in oil paints.

Aditya Sood

Certification to a city cannot be a single matrix. It needs to incorporate different aspects of the city. I would group “Ecological Certification” for cities into 2 categories:

Resource Use Certification

This certification helps control the influence of cities beyond their boundaries.

- Minimal waste: The goal of the city should be towards zero waste. This implies that all the components of a product produced are reused, thus leaving nothing for landfills. This requires a product life-cycle redesign in a way that allows for the reuse of its components. Since most of the industries are in cities, cities can play a significant role in changing the industry practices with the help of incentives and disincentives. The cities could also set up recycling units with active participation from industry.